Dancing Revolution: How ’90s Protests Used Rave Culture to Reclaim the Streets

Thousands gathered on May 16, 1998 in Birmingham’s famous Bullring district, located in the city center. They were instructed to meet by the New Street Station subway stop and make their way towards the Bullring’s roundabout. The mood soon became nothing short of intoxicating as a roaring sound system hidden inside an ordinary car blasted techno to the masses. Fire eaters, drag queens, and clowns were normal amongst a crowd of lamppost climbers and stilt-tripod walkers filling up the streets, creating a gridlock of traffic that purged vehicles from the area and prevented drivers from coming in.

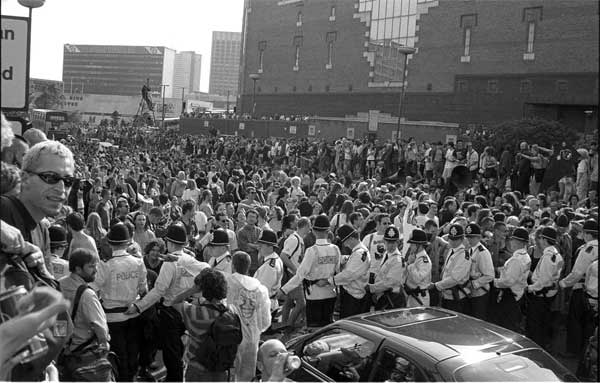

This wasn’t an ordinary Saturday – This just happened to be the second day of the G8 Summit, a three-day event UK Prime Minister Tony Blair had planned to host in the city months prior. In another part of town earlier that day, a human chain had also linked en masse to protest for debt relief. The police in Birmingham were likely preoccupied with the debt relief protesters and protecting the world leaders because by 4:30 p.m., an upwards of 8,000 people had taken over the Bullring roundabout and adjacent side roads, making it nearly impossible for the few officers standing by to do anything.

The road rave even disrupted the foreign diplomats’ route to get to the International Convention Centre where the Summit was held. It wasn’t until after 10:00 p.m. that the police, now in large numbers, were finally able to access the area that’d become a full-on street party. While getting impaled with fruits, vegetables, and insults, the police made it to the sound system and forced the DJ to stop the music.

Birmingham wasn’t the only city raving in the streets on May 16, 1998. The Global Street Party took place in all corners of the world from California, Sydney, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, Berlin, and Israel. On this day, thousands of people ousted cars from the streets in their own city and danced defiantly in a form of resistance.

Orchestrated as part of Reclaim the Streets (RTS), an arm of the international anti-globalization movement, the 1998 Global Street Parties were the height of the RTS’ impact. In just a few years from its launch in the UK, Reclaim the Streets grew to become a highly organized yet disruptive platform to globally fuse politics and revolution with love and parties.

Much like the early raves that hid details of an event until the very last minute, RTS parties were planned with similar clandestinity. Attendees were told to gather at a subway station and once they arrived, a small group of insiders would lead the crowds to the final location which had been kept under wraps. The parties always centered around sound systems pumping techno and acid house, further polarizing the rave as a counterculture against oppressive government and economic policies. This type of guerrilla activism, coupled with a pseudo ‘flash mob rave’ approach to infiltrating public spaces, made RTS one of the most prominent tactics of the 1990s-2000s anti-globalization movements.

There is a familiar phrase in rave culture acronymed as ‘PLUR’, meaning “Peace, Love, Unity, and Respect.” While ravers use PLUR to reinforce civility and decorum among gatherings, in the case of RTS, the party is a battlefield and the public terrain is the dance floor.

RTS has had countless facets around the world. And while the movement uses gridlocks and rave culture to protest, its origin brings the mission down to earth.

Earth First Sound System

In 1989, Mark Davis and Mike Tait along with two other radical environmentalist members of Earth First! decided to target Arizona’s massive canal system by temporarily disabling two pumping stations that redirected water from the Colorado River to desert cities and farms. Everything was mapped out except for one thing – Tait was an undercover agent for the FBI.

Launched in 1980 in Tucson, AZ, the Earth First! organization was already very familiar with legal and media attention by the time of the bust. Touting the slogan, “No compromise in defense of mother earth!” Earth First! took the idea that the wilderness should be free from industrial exploitation to new levels. The FBI used this sting operation to bring charges against Earth First! founder Dave Foreman, but by then, the radical environmental outfit had already built a network of “bureaus” around the world.

When the Earth First! movement came to the UK, the focus was initially centered around occupying timber yards but soon, the protests shifted to occupying roads to halt construction. This distinct Earth First! action would eventually become Reclaim the Streets. But how exactly could the dance-floor-ethos of ‘PLUR’ merge with militant street protests and no-compromise eco-activism?

The First Reclaim the Streets

On May 14, 1995, an old, busted car drove up Camden High Street, one of the busiest streets in London. Even though it was being driven painfully slow, it managed to hit an equally rusted car coming the opposite direction. Both drivers got out of their cars looking visibly upset and started to fight each other, annoying the rest of the drivers who were now stuck in traffic. Both drivers seemed to be so upset that they started to smash up each others’ cars with sledge hammers they’d stashed away. Every car entering the intersection was blocked.

Meanwhile, 500 people came out from the subway station and poured into the traffic-free street. With sound systems powered by the electricity that came from bike pedaling, rave-ready anthems flowed through the street, making it a makeshift party venue. After hearing the commotion outside, nearby shoppers joined in to a scene of free food, toys shared with kids, and banners marked “BREATHE, CAR FREE, RECLAIM THE STREETS!” The police, confused and blindsided, just re-directed the traffic. What else could they do?

Beginning as a seeming act of road rage, the theatrical tactics of the first Reclaim the Streets combined aggressive yet non-violent direct action with ’90s UK rave culture.

“If you want to change the city, you have to control the streets,” states the 1995 flyer of the first Reclaim the Streets. Setting the pace for how the movement would operate in the future, the inclusion of rave DJs was a purposefully grand political statement. Just a year prior, the UK’s Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994 passed containing several sections made to suppress the growing free party and anti-road protest movements happening around the country.

Once the emergence of acid house parties in the late 1980s turned into weekly parties outside the M25 Orbital motorway that attracted crowds of 25,000, the public outrage echoed in the national media. Police crackdowns turned raving into a crime and with the Criminal Justice Bill, the British government made the punishment for holding an illegal party a £20,000 fine and six months in prison.

“Across the world people are taking to the streets, demanding an end to stinking concrete car culture. Direct action against cars, and for increased mobility and safety for cyclists and pedestrians, can take many forms. The emphasis is on celebration.”

Road Alert: Road Protest Camp Tips

By blocking traffic with fake car accidents and other distractions, Reclaim the Streets was able to throw raves in the middle of the day and bypass the legal ramifications of the Criminal Justice Bill. Not only did pedestrians rule the streets, letting rave DJs soundtrack the organized chaos was an extra middle finger to the British government.

However, this isn’t the first time that dancing has been used for protest. There is a longstanding relationship between music, dancing, and politics. In the 1920s, jazz called attention to discrimination while people danced the lindy hop with improvised movements, mirroring how jazz music was improvised. In 1969, Woodstock and other rock festivals protested the Vietnam War and supported the Civil Rights movement.

Ballroom culture has been around since the 60s and has always been a form of protest. But with the emergence of house music in the 80s, the heavily queer scene developed new dance movements in the ‘vogueing’ style which, like death drops and duck walks, have now been integrated in pop culture.

PLUR: Peace, Love and… UnRest??

Some Reclaim The Streets actions and similar events beg the question of just how applications of ‘PLUR’ – (“Peace, Love, Unity and Respect”) define the word “Peace” – as participants may often disagree on what exactly it means to be ‘peaceful.’

The 1998 Global Street Party in Prague started calmly as usual but in the later afternoon, an estimated 2,000 participants started an unauthorized march across the city with a smaller group of those participants breaking the storefront windows of McDonald’s and KFC.

This was one of many events in the ’90s anti-globalization movement where the media spectacle of smashed-up corporate locations highlighted internal movement divisions about tactics. (Historically, protest movements often debate the use of tactics like breaking windows – some insist all property destruction is violent, while others hold that vandalism and breaking windows are valid forms of civil disobedience, and still count as nonviolence if nobody gets hurt.)

Large street celebrations can also quickly turn into safety hazards, a risk organizers are often anxiously aware of. Techno parades in West Germany started in the late ’80s with Love Parade becoming one of the largest and most notorious of the country’s free parties. However, the 2010 edition ended in a stampede, halting the event that had become a yearly German tradition in the unified, once split-in-two nation.

But even among chaos and civil unrest, raving as an act of protest can become an act of unification.

For the first time in its history in 2018, Boiler Room threw their famed streaming party in Ramallah, Palestine, showcasing the thriving underground scene in the war-torn territory. A few years later, Sama Abdulhadi, who performed on the stream and is considered to be Palestine’s first female professional DJ, threw a Christmas rave party in the Nebi Musa Mosque. Although the event was approved by the Palestinian ministry of tourism, she was arrested and detained over two weeks, a move residents believe was made to show political power rather than for reprimand.

“Art without a message isn’t art,” says Ayed Fadel, another Palestinian DJ and promoter. When we look at the message of Reclaim the Streets, it may have started as an anti-road protest but today, it stands as a global demonstration to show all the things that are possible when people occupy the streets and give the cement and tarmacs of public spaces alternative uses. The movement continued to host street parties around the world until the Covid pandemic hit, but that doesn’t signify a finality.

“Direct action, but not just as a tactic.” reads a Reclaim the Streets leaflet. “We advocate a society in which people take responsibility for their own actions, and don’t just leave it to the politicians.” The point of throwing impromptu raves in the street wasn’t just about pressuring governments into action – it was about people taking action to bring awareness to their own interests.

There are many events in today’s headlines that give cause to protest and a road rave is just one example of how we can think globally and act [read: dance] locally. It may be an uphill battle, but as Nietzsche penned, “Those who dance are considered insane by those who can’t hear the music.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: While an archive timeline shows mass adoption of ‘Reclaim The Streets’ as a tactic had mostly fallen off in North America and Europe by the late 2000s, another timeline on Wikipedia documents how Reclaim The Streets direct parties had still been going strong in Sydney, Australia from 2014 to at least 2019.

About The Author: With bylines in Vice, Billboard, and Oprah Daily, Brittany Gaston has been writing about the dance music industry for nearly 15 years. In that time, she also served as a director for the nonprofit Nap Girls working as the head of philanthropy, external events, and intersectionality. Her contributions to Unicorn Riot merge her passion for activism and love of the dance floor. Her work can be followed on social media @runawaytonight.

Title image composite credits: Left photo is by Time’s Up! – via Wikimedia Commons. Right photo © URBAN75 is from URBAN75’s original coverage of June 8, 1996 RTS action on M41 motorway in London.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: