French Police Kill Teen During Traffic Stop, Leading to Mass Revolt

A month before Minnesota law enforcement fatally shot Ricky Cobb II during a traffic stop, police in France killed an Algerian teenager during a similar stop leading to a mass revolt across the country against anti-Black racism. An alarming pattern of deadly traffic stops in France are proving that police in the United States aren’t the only authority figures who regularly kill Black motorists.

Nahel Merzouk, a 17-year-old of Algerian descent, was first stopped by a police patrol in the Paris suburb of Nanterre on June 27 after a chase and then shot at close range when he allegedly tried to evade the identity check by fleeing.

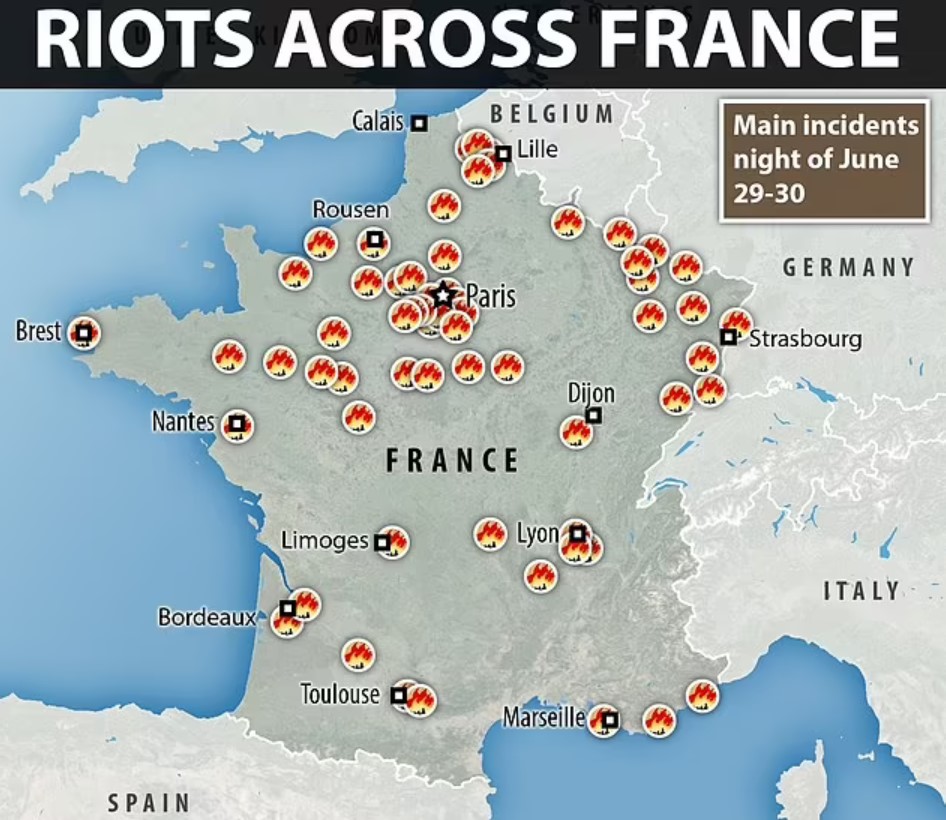

In response to the fatal shooting, mass revolts broke out in Nanterre, other neighborhoods in the Paris metropolitan area as well as the metropolises of Lyon, Toulouse, Rennes, Marseille and other smaller cities and towns across France. The unrest continued for at least six more days and even reached cities in the neighboring countries of Belgium and Switzerland.

Content advisory: the following embedded video features police violence and can be distressing to viewers.

The two police officers who killed Nahel Merzouk initially stated that they were in danger of being run over and fired in self-defense. However, video footage from witnesses shows a different version of the story. Both officers were standing to the side of the car as it started moving again and one of them fired the shots. The car continued to move for about 50 meters and then crashed into a pole. The driver was killed instantly, one of the two other passengers escaped and the third was arrested.

The arrested passenger in the car says one officer urged the other to shoot Nahel at point-blank range. The youth alleged that “the first officer asked Nahel to roll down the window. He told him ‘turn off the engine or I will shoot you’. And he hit him with the gun. Then the second officer arrived and stood in front of the windshield at Nahel’s height. From there, the first officer standing at the level of the window put a gun to his temple and said “don’t move or I’ll put a bullet in your head.”

He went on to report that the second officer told him “shoot him,” and when a frightened Nahel let his foot off the pedal, which was an automatic and not in a parked position, it started moving and the officer in front of the vehicle fired point blank.

The shooter, 38-year-old police officer Florian Menesplier, was taken into custody. An investigation was initially opened against him for intentional homicide and he was placed in pre-trial detention on June 29.

The judges justified his continued detention, citing the risk of further riots, the risk of concerted action with the second police officer present during the traffic stop, and the personal threats against him. Menesplier remains jailed after his detention was confirmed and renewed on August 10.

Menesplier previously served in Afghanistan under France’s 35th infantry regiment and was a motorcyclist with the Direction de l’ordre public et de la circulation (DOPC, Directorate of Public Order and Traffic). Before that he belonged to the compagnie de sécurisation et d’intervention 93 (CSI 93, Security and Intervention Unit 93), which was ordered to disband in 2020. The unit was the subject of 17 judicial investigations for “violence, racist remarks, unlawful arrests, extortion of dealers” and more. He was also a member of the BRAV-M (Motorized Brigades for the Repression of Violent Action), a unit decried for its violence during the Yellow Vests movement, which he joined shortly after its creation on October 1, 2020.

License to Kill – The law of 2017

In 2017, Article 435-1 was passed allowing police officers to fire their service weapons during traffic stops. The law, prompted by then-interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve, came after police union protests following a 2016 incident in a housing estate outside of Paris when an officer suffered serious burns and was put in an induced coma after a group of youths attacked his patrol car with molotov cocktails.

Article 435-1 allows French police to shoot in five instances which include when a driver or occupants of a vehicle ignore an order to stop and are deemed to pose a risk to the life or physical safety of an officer or another person.

This law served as a justification for Menesplier in killing Nahel Merzouk. It was the third killing this year during a police traffic stop, followed by a record 13 killings last year. Most of the victims have been people of color.

Critics argue the increase in killings are a direct result of Article 435-1, which they say is too vague because it leaves officers to determine whether the driver’s refusal to comply poses a risk. Leftist politician Jean-Luc Mélenchon has denounced it as a “right-to-kill” law.

Last year, a study showed there were five times more fatal police shootings of drivers on the basis that they failed to comply with orders since the law was implemented. Last year the police also killed a young woman named Rayana, who was a passenger in a car when the driver ignored a police order to stop.

The Revolt

Starting from the Paris metropolitan area and spreading throughout the whole country, a massive revolt took place in response to the killing. Police stations, schools and other public buildings were attacked, fires were set and extensive looting took place. The main phase of the revolt took place from June 27 – July 2.

Youths organized their neighborhoods through Telegram and Snapchat groups, even creating competitions between neighborhoods on TikTok.

Young people, often second and third generation immigrants of North African and African descent, swarmed the streets calling for justice for Nahel and expressing grievances of feeling increasingly wronged, forgotten, segregated and alienated from the rest of French society.

During the period of June 27 – 28, over 3,400 people were arrested, over 12,200 vehicles were set on fire, 1,105 buildings were burned or damaged and 209 national police premises were attacked.

History of Banlieue Unrest

The widespread revolt, fire, anger, and unrest thrust the spotlight onto the French banlieues, or suburbs. The term banlieue has often been used to describe “troubled” suburban communities — those with high unemployment, high crime rates, and a high proportion of residents of foreign origin mainly from former French African colonies. For many in France, the word “apartheid” has been used to describe the social conditions of the banlieue in terms of an ethnic, social and territorial separation.

Starting in the 1950s, the French state built large high-rise housing estates (cités in French), in the banlieues of France’s larger cities such as Paris, Lyon, and Marseille, where mostly low-wage industrial workers found comfortable housing for the time. The aim was to alleviate the massive housing shortage in urban areas. This had arisen due to a severely outdated and dilapidated building stock in the core cities and war damage.

The process of deindustrialization that began in the mid-1970s subsequently led to an impoverishment of the proletarian households concentrated in the cités. The cités evolved from “centers of transformation and modernity” to “places of social decline.“

Unrest in the segregated French suburbs is nothing new. The first banlieue riots occurred in 1979 in Vaulx-en-Velin, a poor suburb of Lyon, when a teenager slit his veins after an arrest for stealing a car. Events of banlieue unrest continued throughout the 90s, 00s and 10s in different metropolitan areas, mainly after incidents of police violence.

After the murder of Nahel, many looked back to 2005, when two teenagers, Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré, died in Clichy-sous-Bois near Paris. They hid from police in an electrical distribution box after police attempted to conduct an identity check on them and were electrocuted. The reaction to the killing was similar: over 10,000 cars demolished, buildings on fire, 6,000 arrests and 130 people injured.

The 2005 Paris Banlieue Riots were widely considered the most important uprising in France since the 1968 uprising but were interpreted by many mainstream media outlets as non-political and aimless violence rather than political dissent.

The State Strikes Back – French police counter insurgency

After two fiery nights, major cities in France were besieged by heavily armed police forces with helicopters, armored vehicles and firearms. Special RAID units (Research, Assistance, Intervention, Deterrence) were deployed in Nanterre, Marseille and Lyon, invading neighborhoods with armored vehicles. The notorious BRAV-M units, which provoked and terrorized demonstrators in Paris in April during protests against Macron’s pension reform, were also deployed.

- Wednesday, June 28

- After words of compassion for the “unforgivable” crime, President Emmanuel Macron denounced the widespread protests as an “unacceptable exploitation of the death of a teenager.”

- Thursday, June 29

- 40,000 police were mobilized overnight. The suburb of Clamart along with a few other towns declared a 9 p.m. curfew. Bus services were stopped at 9 p.m. and the sale and transport of fireworks, petrol cans and other flammable liquids were banned.

- Far right politician Jean Messiha started a GoFundMe campaign to support Menesplier and his family. It has eclipsed 1.6M Euro. Despite widespread criticism against GoFundMe, the platform continues to allow the fundraiser to raise funds . In contrast, a 2019 fund to support a former boxer who was filmed punching police officers during anti-government demonstrations was closed down very quickly.

- Friday, June 30

- Court cases against protesters were fast tracked. From Le Monde: “In one of the courtrooms, five young people were on trial for rebellion, violence against police officers, and damage to property. While they acknowledged their presence at the scenes, they all pleaded it was a coincidence, saying they had been in the wrong place at the wrong time. But the court was not easily convinced. It took no more than 15 minutes of deliberation to come to a decision, which resulted in three of the young people being sentenced to prison terms, with a committal order at the end of the hearing.”

- Saturday, July 1

- French President Macron blamed the uprising on video games and social media, “It sometimes feels like some of them are experiencing on the streets the video games that have intoxicated them.”. Almost a third of the 875 people arrested on June 29 were minors.

- A 27-year-old protester was killed by police during clashes in Marseille in southern France. The young married man was hit by a flash-ball bullet (LBD), a type of “non-lethal” crowd control weapon used to suppress demonstrations. His wife said he was taking pictures when he was shot. An investigation has been launched into the man’s death.

- Monday, July 3

- Following multiple attacks on town halls and the targeting of a mayor’s private house in south Paris, Macron met with hundreds of mayors of towns that were being hit by the riots. They organized gatherings in front of town halls across France – uniting politicians of different parties. In the Paris suburb of L’Haÿ-les-Roses, hundreds of people gathered in support of Mayor Vincent Jeanbrun, whose private house and family was allegedly attacked by protesters. Crowds also gathered in front of city halls in other places throughout the country affected by violence to express their solidarity with mayors and city councils. According to the Ministry of Interior, a total of 99 city halls had been attacked.

- At the same time, videos circulated in social media from small fascist groups patrolling in city centers – like in Lyon or Angers – in some cases accepted by police, but also chased by protesters.

- Wednesday, July 5

- French legislators approved a bill allowing police to remotely activate cameras, microphones, and GPS on suspects’ phones. The measure applies to suspects involved in crimes that are punishable by a minimum of five years in jail. Police are now able to take video and audio recordings of suspects through remote access to their phones. In practice it means that even with VPN services or encrypted messaging, avoiding government surveillance with a registered phone will nearly be impossible.

In the aftermath of the riots, more than 1,050 people were convicted of crimes and about 740 sent to prison, while others received suspended sentences.

‘Justice pour … for Ibrahima, truth and justice for Theo, justice for Steve, for Adama, justice for all! Justice for Nahel!’

The suburbs are not known for their willingness to accept institutional racism and violence from the French state without a fight. In the last 20 years, as police killings continue to rise in numbers, communities have come together across the Banlieues and form new forms of rallying and militancy against the police violence they face. Committees are being set up to help families garner support in forms of basic legal help to investigatory support and community building. Friends and relatives regularly band together and demand justice, the release of videos, and proper investigations.

Central to the development of this movement are people like Assa Traore, sister of Adama Traore, who died in custody after being apprehended and restrained by police in 2016. His death is reminiscent of that of George Floyd.

Assa’s fighting spirit to get justice for her brother has given new characteristics to the European anti-racist struggles, which in many countries were mainly initiated by white militants with a sense of awareness and solidarity. In the same as Eric Garner’s killing in 2014 in New York City, Adama’s last words were “I can’t breathe.” This phrase reverberated through European immigrant communities of the suburbs expressing the tragedy and suffocation.

These struggles are a reminder that Black and Brown lives still don’t have the same importance in postcolonial France, making it clear that racism and racial inequality is not only an issue of concern in the USA. Police violence against Black people is a global reality and the next generations across the globe continue to express their discontent.

Niko Georgiades contributed to this report for Unicorn Riot.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: