Thousands of Asylum Seekers Stranded Along Border Wall Near Sasabe, Arizona

Sasabe, AZ — The afternoon sun cut diagonally through the 16-foot-tall concrete-reinforced steel bollards marking the international boundary between the United States and Mexico east of Sasabe, Arizona. The wall’s long shadows cast a strobe light effect on cars passing along the roughly graded road cut into the mountainside along the U.S. side of the desert.

Along the road, migrants walked in groups of five or ten, men, women and some children, carrying backpacks of clothes and supplies. They were bundled in coats, and some wore turbans, others baseball caps. All together, perhaps 50 people made their way along the road, walking the 15 miles to the Sasabe.

They held out their thumbs to passing cars, mostly humanitarian aid workers, in hopes of catching a ride as the setting sun foretold dropping temperatures.

The migrants, most of whom hailed from oceans away — from the Indian subcontinent and from Africa — were not passing through the rough desert areas along the Southern Arizona border in hopes of evading capture by Border Patrol. They walked openly down the road in hopes of arrest. Their destination: the Border Patrol Station in Sasabe, where they have been turning themselves in in droves since early November to petition the U.S. government for asylum.

At times, hundreds of people have huddled in makeshift camps near the border wall, struggling to stay warm under tarps amidst rain and freezing temperatures.

“There’ll be times where there’s fifty screaming babies, just forced to stay here overnight,” said Bryce, a volunteer with No More Deaths, a humanitarian aid organization in Southern Arizona that has been responding to the crisis.

“And all this crap,” Bryce said, gesturing to the rows of tarps and billboard canvas affixed haphazardly to the border wall itself, “we put up on a day that was just really rainy and cold, there was historic rainfall. And there was nothing here, there were no tents, there was no anything. And our goal was just to sort of keep people alive until Border Patrol could come pick them up.”

But then Border Patrol didn’t come.

“This stuff wasn’t meant to last more than just a few hours,” Bryce said. “But it was just completely full of kids, women. There was a different medical emergency, probably every half hour, it was just this really, really horrible situation in which a lot of people probably could have died.”

The lack of emergency medical response from 911 services that night was not at all atypical. In fact, No More Deaths volunteers have extensively documented a pattern of Pima County 911 dispatchers segregating emergency calls involving migrants to Border Patrol. In many cases, Border Patrol does nothing.

“The response of local authorities is separate and unequal,” the group wrote in their report, Separate and Deadly, “whereas county-led search, rescue, and medical services respond to reports of US citizens and foreign tourists in distress in their jurisdiction, they almost never deploy a response for people who they suspect have crossed the border.”

Related: Humanitarian Arrested After Group Releases Report Implicating US Border Patrol [Jan. 2018]

This failure on the part of Pima County emergency medical services to respond effectively to migrants in crisis has deadly results. “In 63% of the cases we reviewed, the border enforcement agency took no action whatsoever to search for migrating people in distress,” the group wrote. “In the few cases in which Border Patrol did deploy a confirmed response, 10% ended in the known death of the person in distress…Comparing these statistics with the near-100% success rate of county-led search and rescues in Pima County, it becomes clear that the bifurcation of emergency services along citizenship lines constitutes a form of deadly discrimination.”

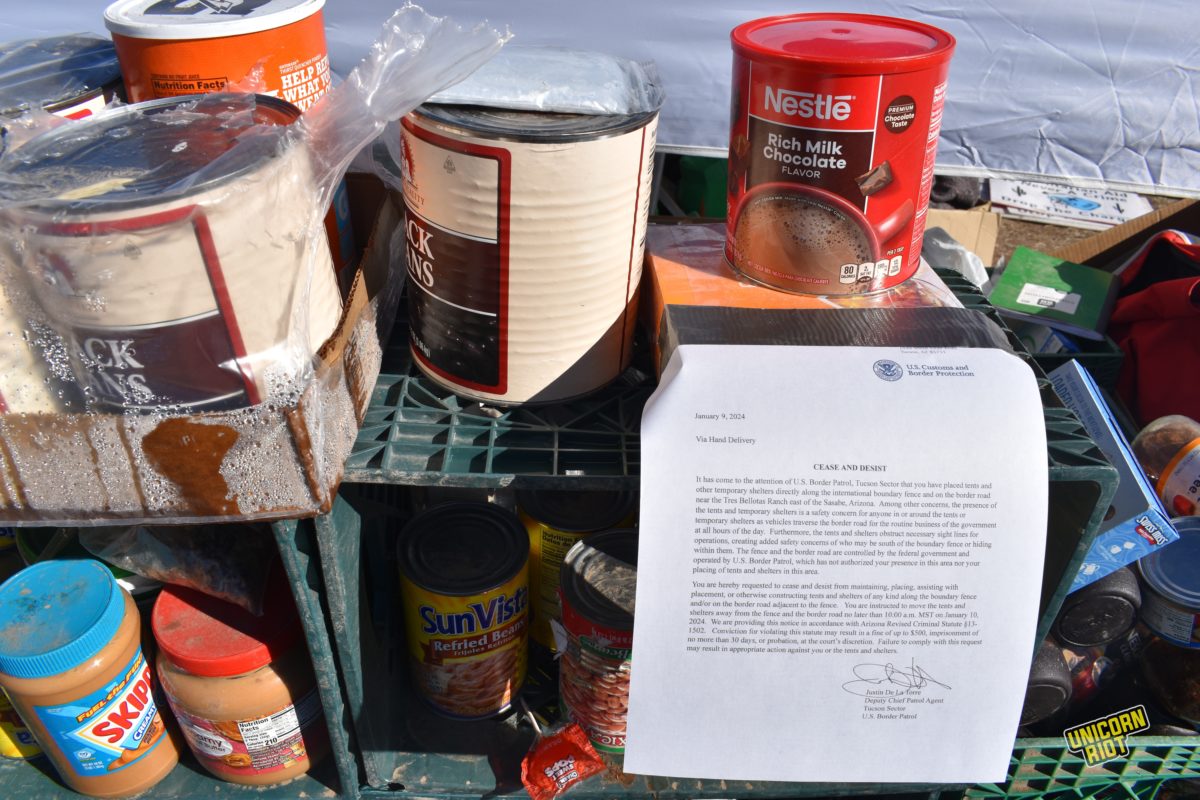

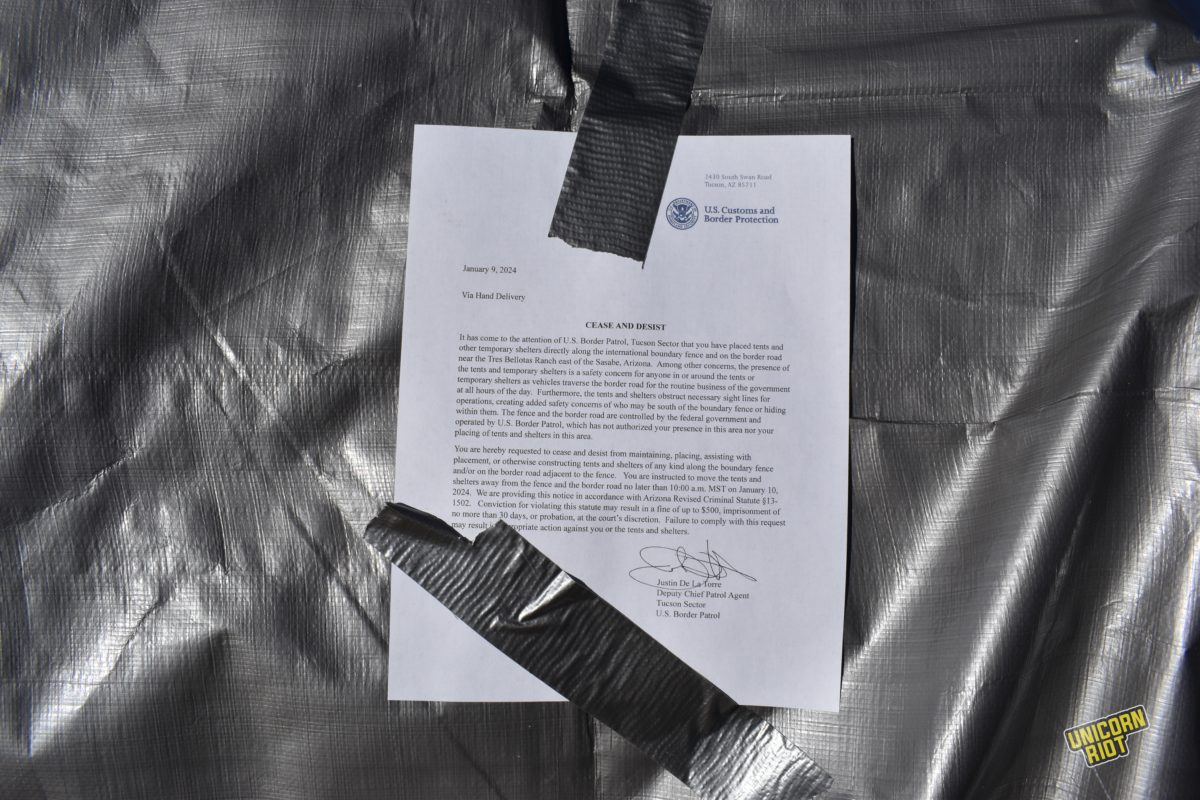

Rather than supporting the efforts of humanitarian aid workers trying to keep migrants alive, Border Patrol entered the aid camps Tuesday and taped ‘Cease and Desist’ notices on Customs and Border Protection (CBP) letterhead to structures, food supplies and water dispensers.

“You are hereby requested to cease and desist from maintaining, placing, assisting with placement, or otherwise constructing tents and shelters of any kind along the boundary fence and/or on the border road adjacent to the fence,” the letter read. “The presence of the tents and temporary shelters is a safety concern for anyone in or around the tents.”

The notice was signed by Justin De La Torre, Deputy Chief Patrol Agent for the Tucson Sector of the U.S. Border Patrol.

The letter was taped to structures within the humanitarian aid camp more than 100 feet from the edge of the border wall, on land not under the jurisdiction of CBP. Border enforcement agencies only have jurisdiction over a 60-foot-wide strip of land along the border, called the Roosevelt Reservation–created in 1907 by President Theodore Roosevelt to give the federal government the ability to freely access and police its asserted southern border.

A CBP spokesperson clarified to Unicorn Riot that the notices were only intended to address the structures built alongside the border wall. The agency has no intention, nor right, to clear the camp itself, the spokesperson clarified.

Since Title 42 ended in May 2023, those seeking asylum in the U.S. are frequently released into the country after passing a ‘credible fear’ interview establishing that they faced significant threat of persecution, torture, or death in their home country. Asylum seekers are given a court date, often many months in the future, but are allowed to live in the country while their case proceeds slowly through the heavily backlogged immigration court system. Many join their family members already living in the U.S.

Unfortunately, getting a credible fear interview is increasingly difficult.

“Currently, people are prevented from presenting for asylum at the port of entry, they’re turned back, unless they have a CBP One appointment,” said Bryce. CBP One is an app distributed by CBP that asylum seekers are forced to use to make an appointment before presenting at a port of entry. “For a million different reasons, it’s either difficult or impossible for a lot of people or often people will be stuck in a dangerous border town for up to a year at a time or more [waiting for an appointment] and end up not being able to wait any longer in unsafe conditions.”

This digital bureaucracy is pushing asylum seekers into the desert and onto the statistical tables of Border Patrol, where they’re driving up apprehension numbers.

“There were 300,000 apprehensions in December alone all across the border,” said Ary, a No More Deaths volunteer, “but why that number is ‘record high’ is that so many of those people are trying to seek asylum. So Border Patrol, in their apprehension numbers, is including people they’re apprehending along the border wall whereas those people are legally supposed to be able to present at ports of entry.”

Instead, they’re entering the country in remote areas like the area east of Sasabe, where the border wall is highly porous. They’re crossing in hopes of being picked up quickly by Border Patrol to present their claim. “Because they’re seeking asylum, they’re not prepared for some long stay in the desert,” said Bryce. “They’re coming through with just the clothes on their backs, maybe a little day pack or something hoping or thinking that they’re gonna get picked up very quickly by Border Patrol. There’s children, families, people with really severe medical problems expecting Border Patrol to come and they just kind of don’t.”

Since the influx of migrants in this zone began in early November, individuals and groups throughout Southern Arizona have begun gathering supplies, building makeshift shelters in the desert to protect migrants from dangerous weather conditions, and providing humanitarian aid to thousands of people en route to the U.S.

The efforts have been spearheaded by No More Deaths, which established organizational tools to allow for a decentralized, largely self-organized, humanitarian response to emerge. The efforts, which are based largely in Tucson, have used two autonomous community centers—the Global Justice Center and the Blacklidge Community Center—where volunteers have held informational sessions about the ongoing situation and gathered supplies to transport to humanitarian aid camps along the border.

“There’s been a really amazing community effort to support what’s currently going on here,” said Ary. “Folks in Tucson have rallied together to do clothing drives, cooking a bunch of food, bringing it down to the wall. There’s been people who have four-wheel drive vehicles driving down and supporting with medical care, making meals for 100 to 300 people every day.”

“We really need community support, and it’s been so special to see all of the people come together and help make this disaster a little bit lighter on all of us.”

Starting January 11, the drop off location for supplies moved from the Global Justice Center to the Blacklidge Community Center in Central Tucson. Volunteers are staffing the drop off location Tuesdays and Thursdays from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m. and Saturdays from 12 p.m. to 4 p.m.

Read the full report Separate and Deadly: Segregation of 911 Emergency Services in the Arizona Borderlands. The report is part four in a collaborative project between two Tucson-based organizations, La Coalición de Derechos Humanos and No More Deaths:

See past Unicorn Riot reporting on the humanitarian work of No More Deaths and watch our 2017 mini-doc Crisis: Borderlands.

Humanitarian Camp Raided by Border Patrol and BORTAC, 30+ People Arrested [Aug. 2020]

Migrant Aid Workers Targeted by Border Agencies in Retaliation, Documents Suggest [March 2019]

Humanitarian Arrested After Group Releases Report Implicating US Border Patrol [Jan. 2018]

Humanitarian Aid Camp Raided By US Border Patrol [June 2017]

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: