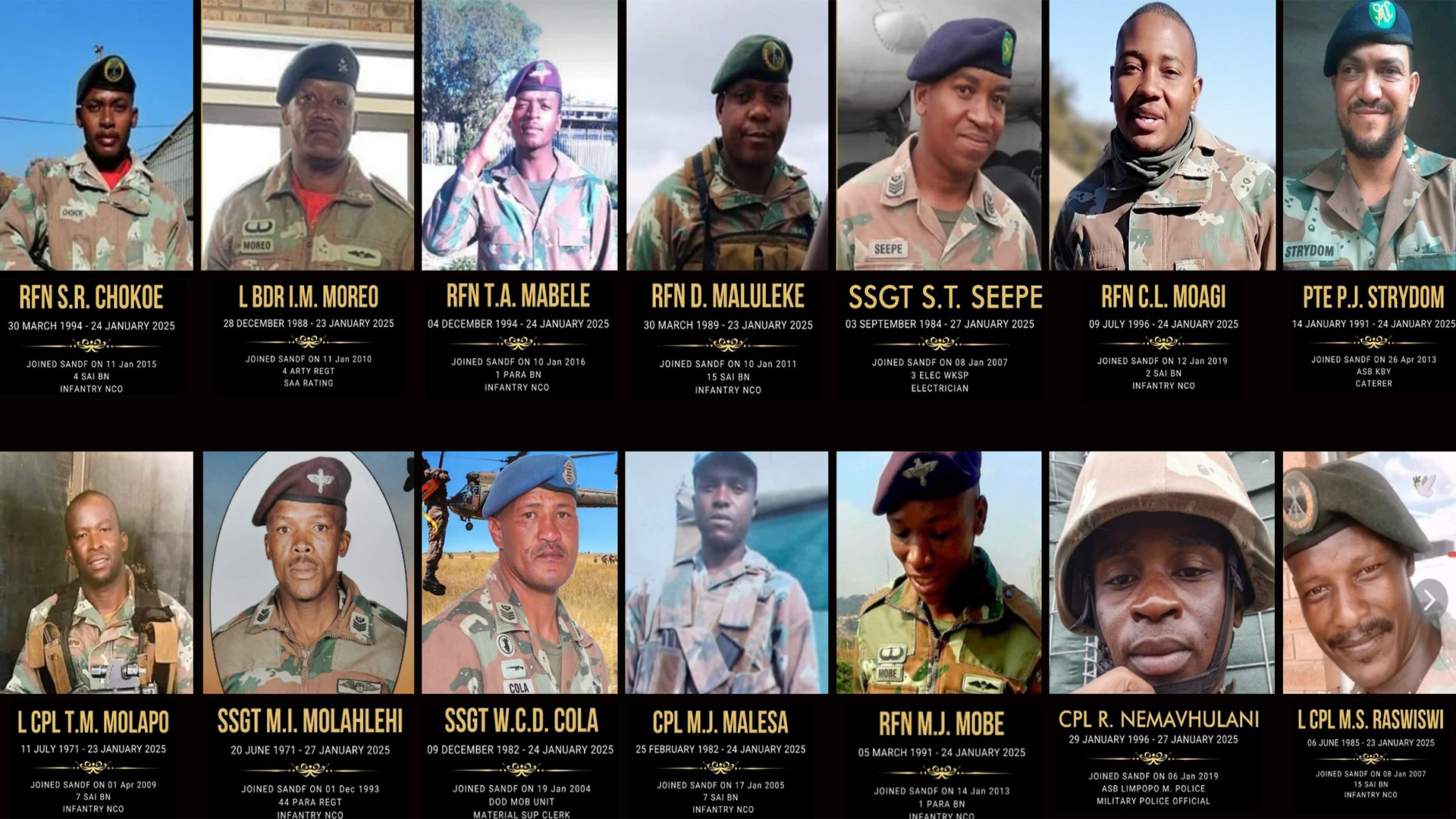

Fourteen South African Troops Killed as Congolese War Escalates

Durban, South Africa — Renewed fighting between rebels and government forces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s North Kivu province has resulted in the deaths of 14 South African soldiers. The fallen troops were a part of two separate international “peacekeeping” missions aimed at supporting the Congolese government in combating over 100 different armed groups that currently operate in the country.

One armed group in particular, known as the March 23 Movement — or “M23” for short — has again seized headlines for launching a stunning attack that pushed Congolese government forces out of the strategically important city of Goma in late January. It was during this battle that the 14 South African troops were killed, attempting to hold back the rebel advance.

An online video began circulating purportedly showing South African troops deployed in Congo, waiving the white flag — a gesture universally recognized as a symbol of surrender. The South African government however denied that its troops had officially surrendered, claiming instead that the white flag was to signal a temporary truce so that both sides could recover its dead and wounded from the battlefield.

WATCH & READ: The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) has dismissed rumors circulating on social media that South African soldiers have surrendered to M23 rebels in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

— The Political Playground ⚫⚪ (@ThePPLiveSA) January 28, 2025

According to the SANDF, a video showing a white flag being… pic.twitter.com/lfOgWLCwh4

Around 3,000 Congolese people have also been reportedly killed in the recent battle for Goma, while many more are believed to have been displaced due to the fighting there. Scores of Congolese government soldiers were also reportedly captured, some of whom crossed into the nearby country of Rwanda to surrender along with hundreds of European — mostly Romanian — mercenaries. After gaining complete control of Goma on Jan. 30, M23 continued pushing into government held territory in North Kivu, threatening to “go all the way to Kinshasa” — the capital city of Congo.

M23 offered the South Africans safe passage through neighboring Rwanda to transport their dead back home, but in exchange demanded that the South African military completely withdraw all of its troops from Congo. Ordinarily the South Africans would have used Goma’s airport to do this, however due to heavy damage sustained during the battle, the airport has remained closed. After a week of negotiations, it was finally agreed that the bodies of the deceased South Africans would travel through Rwanda to Uganda and ultimately their final resting places in South Africa. The deal notably did not include the removal of South African troops as initially demanded by M23.

As of the writing of this article, hundreds of South African soldiers remain stranded and surrounded by M23, mostly confined to their bases in Goma, and the nearby town of Sake. M23 has also closed the airspace around them utilizing drone signal jammers and anti-aircraft weapons reportedly supplied to them by the Rwandan military.

Simultaneously, domestic pressure continues to mount on the South African government to send its troops back home, as many South Africans are just now becoming aware that their soldiers are deployed there. But South Africa’s military presence in Congo is nothing new, as since 2009, thousands of South African soldiers have been deployed to Congo. These soldiers are part of an ongoing U.N. peacekeeping mission known as the “United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo,” or “MONUSCO.”

South African Military Involvement in Congo

The U.N. peacekeepers in Congo officially maintained a neutral approach limited to mostly observing the conflict and assisting with humanitarian aid delivery. However, a major shift in tactics occurred in 2013 when the U.N. authorized its peacekeeping forces to actively pursue and eliminate M23’s presence in the Congo. This event marked one of the very few times in history when the U.N. sanctioned its peacekeepers to take offensive action to dismantle specific armed groups.

To complete this task, a separate organization within MONUSCO was formed, aptly named the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB). The FIB is staffed by the South African Army but also includes smaller elements of the Tanzanian and Malawian armed forces. The FIB was ultimately successful in its 2013 mission to root out M23, pushing them out of Congo and across the border into Rwanda and Uganda. The forceful hand with which they used to evict the rebels, however, was met with opposition and concern from the wider U.N.

Critics pointed out that the FIB’s offensive actions violated the core principles of peacekeeping, i.e. conflict observation and resolution – not intervention. Furthermore, it meant that the U.N. peacekeepers in Congo could no longer be considered neutral observers and would now be treated as legitimate targets for attacks by M23 and other armed groups.

This is exactly what happened after the FIB’s victory against M23 in 2013. They continued to pursue and attack other anti-government rebel groups in the region, sustaining heavy casualties in the process. Dozens of U.N. troops have been killed in Congo since, with the South African Army alone having sustained at least 21 fatalities to date. This caused the U.N. to once again change course in 2017, as it has been began steadily withdrawing its troops since.

In response to the U.N. pullout in 2023, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) — an intergovernmental organization that’s part of the wider African Union — announced that they would be sending their own “peacekeepers” to Congo to replace the FIB. Just like the FIB, this new force would be comprised mostly of South African troops.

Unlike the FIB however, the overall cost for the AU force would not be covered by the U.N. — more specifically the Europeans — and would have to rely primarily on African funding. However, South Africa’s commitment of $100 million, combined with a Congolese investment of about $200 million is far short of the mission’s roughly $500 million annual price tag.

And so despite official statements that around 3,000 SADC peacekeepers would be deployed to Congo, there is uncertainty over whether that’s actually the case. As recently as Feb. 10, South Africa reportedly sent an additional 700-800 troops, further indicating that its garrison in Congo was not at full strength.

Ongoing budgetary constraints and the continued decline of the South African military budget have also raised further doubts about the logistics, equipment and the overall ability of the South African military to combat the large and diverse variety of heavily armed groups in Congo — not least of which includes the Rwandan Army.

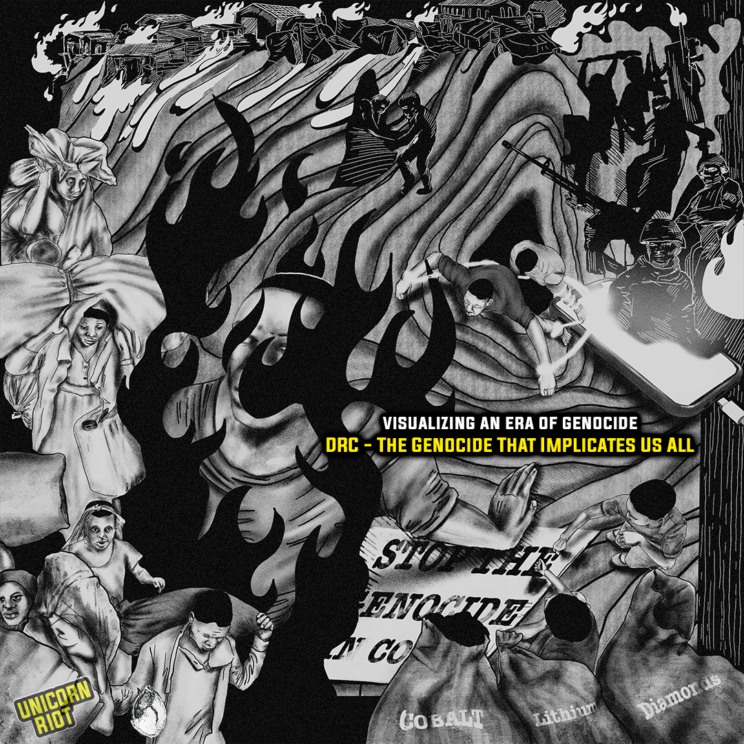

Rare Earth Minerals and Ethnic Tensions Fueling the Conflict

The biggest funding source of the ongoing conflict in the Congo revolves around its most valuable commodity: rare earth minerals. These include the world’s largest known reserves of precious metals like cobalt, coltan and copper – all of which are needed to produce the electronic devices that our world has increasingly come to depend on.

While reliable data on the mining industry in Congo is sparse, most current estimates place the country’s untapped mineral wealth at around $24 trillion. Despite this enormous wealth potential, Congo remains one of the poorest nations on earth, where those fortunate enough to find a job as an artisanal miner can expect to make around $3 a day or less.

The majority of the profits generated from these vast mineral deposits are funneled into foreign and state-owned companies. Historically those companies have mostly been based in Europe, but in recent years the industry has become dominated by Chinese investors.

Congolese rebel groups are also known to be heavily involved in the environmentally destructive mining business, as “conflict minerals” are extracted from the mines within the areas they control and smuggled into neighboring countries for handsome profits.

Rwanda has also been accused of using M23 to illegally smuggle tons of rare earth minerals from Congo into Rwanda. While there’s no physical evidence that directly implicates the Rwandan government in this, the Rwandan state has made substantial profits from conflict minerals.

For example, about 80% of the world’s known cobalt reserves reside in Congo, yet since 2014. Rwanda has consistently outpaced Congo as the world’s largest coltan exporter. Analysts therefore believe that a considerable, yet unknown amount of Rwanda’s coltan exports were illegally smuggled from Congo.

Ghosts of European Colonialism and the Rwandan Genocide

The biggest factor driving the current conflict in Congo, however, is not what some have coined “Africa’s resource curse” but rather longtime political and ethnic divisions that persist amongst some 700 different ethno-linguistic groups. This exceptional tapestry of different peoples places Congo as one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world.

Like many of the other rebel groups in the region, M23 is the byproduct of the Congolese/Rwandan civil wars and the 1994 Rwandan genocide in which nearly 1 million ethnic Tutsis were killed in 100 days by ethnic Hutu fanatics.

M23 is primarily made up of Tutsis living in Congo who have close connections and affinity with their Rwandan Tutsi counterparts across the border. Their opponents use this connection to claim that the Congolese Tutsis are not Congolese people, but are Rwandans. Most historians generally agree that the Tutsis living in the Congo are the descendants of multiple waves of emigration from Rwanda. When exactly the first mass migration occurred is still debated, though the general consensus is that they have been living in Congo for at least hundreds of years.

Congolese Tutsis that live in Congo are part of a separate supra-ethnicity called the Banyamulenge, which includes multiple ethnic groups from Rwanda — most prominently the Tutsis.

Unicorn Riot spoke with Nshuti Alex, a Rwandan Tutsi immigrant living in South Africa studying architecture. When asked about the origins of the Banyamulenge they explain:

“The Banyamulenge are a mix of many different peoples including the indigenous peoples who lived in the Congo before colonial times. They speak [the Tutsi language] but they are not the same.”

Longtime Rwandan President Paul Kagame is himself a Tutsi who rose to power after leading the Rwandan Patriotic Front — or RPF — to victory over the Hutu-dominated Rwandan government in 1994, thereby ending the genocide. Kagame and the RPF have since gone on to rule Rwanda as a defacto one-party state that has become notorious for ruthlessly hunting down and assassinating its political enemies both within and outside of its borders. Various human rights organizations, news outlets and dissidents have documented incidents of political repression by the RPF, which they argue has had a chilling effect on Rwandan politics.

Despite his iron-fisted approach, Kagame has maintained an almost cult-like status amongst his supporters, both for ending the genocide three decades ago, and for the notable improvements of Rwanda’s infrastructure and economy under his rule. This has been the key to maintaining his longtime dominance over the country, as Alex admits:

“You can say [Kagame] is not a very democratic person and those criticisms are true, but also, there are many wars he had to fight, and many wars he is still fighting […] he has to be a strong man because the situation demands it, if not, Rwanda may suffer the same problems that we are watching now in the Congo.”

Immediately following Kagame’s victory in the civil war, nearly 2 million Hutus fled Rwanda into Congo. Many of the perpetrators of the genocide left with them, opting to continue attacking the Rwandan military in cross-border attacks from their Congolese bases. In the past, Rwanda has acknowledged and justified its previous military adventures into Congo under the excuse of needing to protect both Rwanda and the Tutsi population living there.

In the present day however, despite extensive evidence documenting the presence of Rwandan troops in Congo, Kagame continuously refuses to acknowledge that his troops are directly involved. When recently asked by a CNN reporter on whether Rwandan soldiers were present in Congo, he simply replied “I don’t know.” He has also issued veiled threats to the South Africans stating that “should the South Africans prefer confrontation Rwanda will deal with the matter in that context any day.”

Future Outlook

When divvying up the African continent amongst themselves, European imperialists widely disregarded pre-established African boundaries, customs and culture, while actively pitting its exceptionally diverse ethnic populations against each other.

German, and later, Belgian colonists employed the strategy of divide and conquer in Rwanda by initially propping up a Tutsi aristocracy to rule Rwanda on their behalf, over the more populous Hutu working class. As the post-World War II wave of African nationalism came to Rwanda, the Belgians swiftly reversed course and began to support the Hutus, contributing greatly towards the deep-seated ethnic hatred and rivalry that continues today.

These artificially inflated ethnic divisions were key in keeping the local African population fighting amongst themselves, while shipping as much of the continent’s natural resources to Europe as possible. Not much in this arrangement has changed in the 21st century, the primary difference now being that there are many more players and political alliances vying for control, money and influence over the region.

Currently, it appears that M23 has all the momentum as it continues to push deeper into Congolese government territory. Many question whether they’ll actually be able to reach the nation’s capital located some 1,000 miles away from their current positions. What can’t be questioned is that they and the Rwandan state are now the dominant force in a key region of Congo that supplies the majority of the world’s cobalt.

How Congo’s government, the people of Congo and the wider African community respond to this will ultimately decide the course of the current conflict and whether it can be resolved peacefully through a negotiated resolution, or further war, displacement and destruction. Either way, M23 and the Rwandans have made the message clear: they’re still in the neighborhood and they’re there to stay.

[Note:”Nshuti Alex” is a pseudonym used to protect their identity]

[Cover Image: South African Department of Defence]

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: