Pro-Palestine Festival Artists Boycott Israel-Linked Company

Musicians speaking out against Israel has become a mainstream topic as artists are using famous festival stages to express their opposition against the ongoing genocide. Consequences followed swiftly, with Manchester’s RADAR cancelling Bob Vylan’s performance and Kneecap facing legal action after Glanstonbury. In the electronic music world, an entire pro-Palestine movement is now gaining momentum.

Over the past couple of weeks that world has been shaken up by news of a beloved large scale festival becoming owned by one of the most notorious private equity firms in the industry. The initial news of Barcelona-based festival Sónar – which took place 12-14 June, 2025 – being bought by Superstruct Entertainment flew under the radar. Superstruct itselft was purchased by private equity giant Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co in 2024.

A wave of concerned artists signed an open letter and withdrew en masse from the festival because of KKR‘s ties not only with Canada’s Coastal GasLink pipeline, but also connections (archive) to Israeli settler housing in the occupied West Bank. The Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) later officially called for a boycott of the festival. Here is all you need to know about how this happened and why it matters.

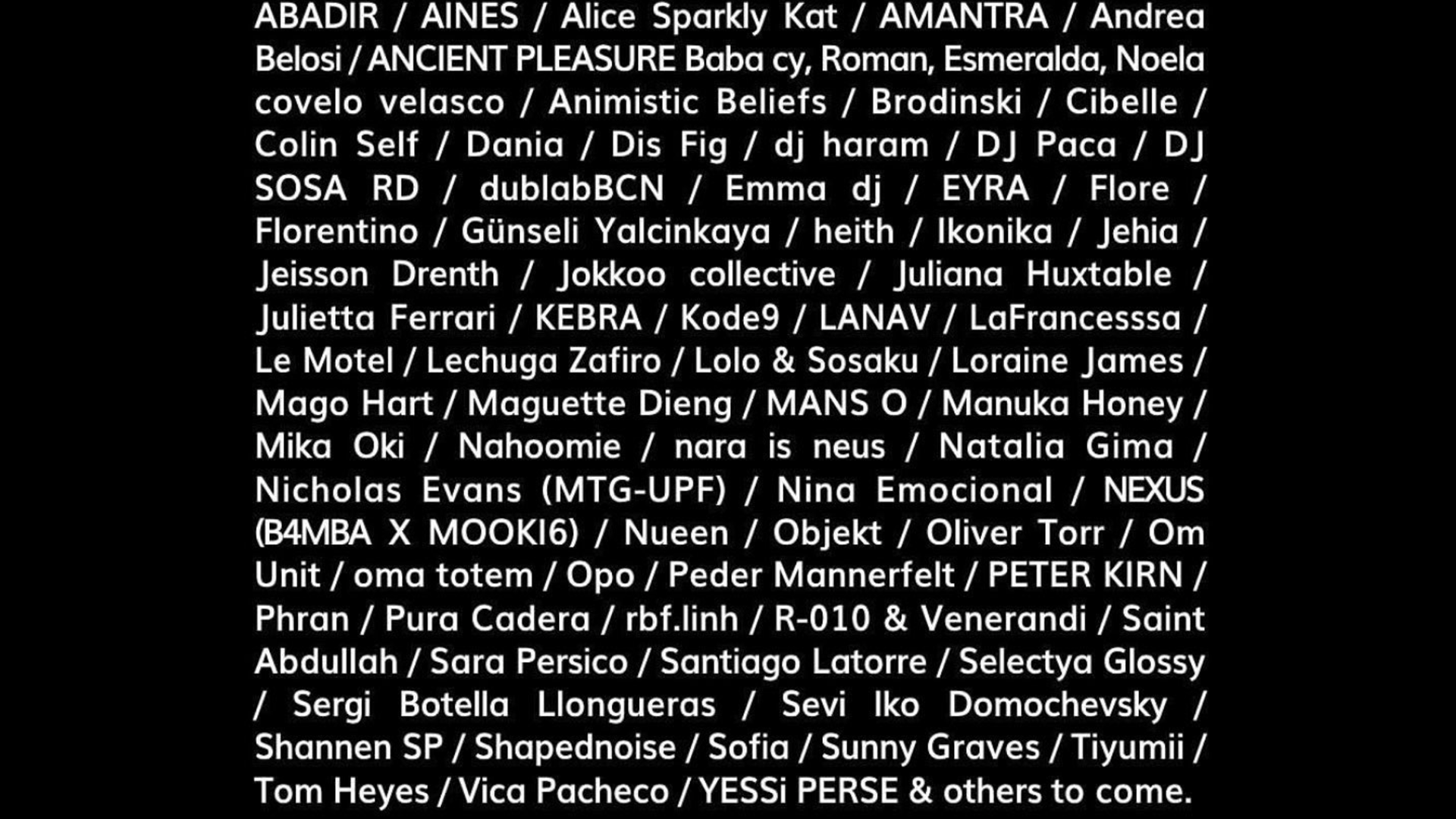

In response to Sónar‘s parent company being bought out by KKR, a large number of artists have withdrawn from the festival. Animistic Beliefs, a self-described “bi-cultural” duo based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, were one of the artists that led the charge. “We’re stepping away because Sónar is owned by Superstruct, which is backed by KKR – an investment firm that has profited off war, climate destruction, and systems of oppression for decades. We don’t want to be part of that,” they wrote in an Instagram post dated April 21st 2025. “We know no space is free from contradiction. But somewhere, the line has to be drawn. Maybe you’ve felt something like that too. For us, it stops here,” their statement says. More names such as Julianna Huxtable, ABADIR, James Ferraro, Colin Self, Manuka Honey, Loraine James, Objekt, dj haram, Ikonika and others followed by withdrawing in early May. An open letter asking the organizers to adhere to boycott, divestment & sanction (BDS) guidelines with more than 150 signatories from editions past and present also circulated.

On May 30th, Sónar issued an official statement in response to the online backlash. Despite their best efforts to spin the situation and distance themselves from their new corporate owners, this only added fuel to the online fire. On June 3rd, PACBI called for an official boycott of the festival, asking participating artists to withdraw. The wave of cancellations culminated with the sudden withdrawal of Arca, who didn’t make a statement.

“The calls to boycott have demonstrated a diversity of positions among party-goers about Palestine and Israel and opinions about the agency of artists and ravers to influence the corporate owners of these popular events and platforms,” artist, researcher and fugitive radio host Sumugan Sivanesan says. “I think it is significant that certain artists have chosen to withdraw and there is much organizing around this, such as alternative gigs and strike funds, which I’d suggest is an indicator of change.”

Barcelona is one of the most vocally pro-Palestine cities, especially in Europe. Its mayor Ada Colau called for Israel to “end the system of violations of the Palestinian people” in February 2023, suspending their twinning status with Tel Aviv. In June 2025, current mayor Jaume Collboni and his party finalized the decision.

Private Investors & KKR Move into Festival Industry

Sónar is one of the largest festivals in what might be considered a loose global, and particularly European, network of electronic music festivals such as the CTM festival in Berlin, Unsound in Krakow, Mutek in Montreal, Rewire in The Hague and Nuits Sonores in Lyon. These are some of the largest sources of income and visibility for artists in the global industry. Prestigious music and digital arts festivals predominantly take place in cities and often benefit from financial support from their regional administrative bodies. For many of the artists who chose to withdraw from this year’s edition, it has not been an easy decision.

A week before Sónar was set to start, Barcelona-based artist and emergency doctor Dania Shihab talked on Al Jazeera English podcast The Take about the show she was about to premiere and the process of negotiating her cancellation. “It wasn’t sort of an overnight decision — we tackled the issue as a community,” she says. The initial discussions took place in a diverse WhatsApp group of 30 Barcelona-based artists. “The conversation started to gain momentum when we found [out] that the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divest and Sanctions were actually getting involved and they were in contact with a lot of international artists that were playing Sónar.”

The fact that KKR was the parent company became the tipping point for a lot of artists. For Shihab and many others, learning the level of complicity in the Palestinian suffering of KKR came as a surprise. “They have data centers that are in occupied Palestinian land, they’re involved in weapons manufacturing through Novaria Group,” she said on the podcast. She also mentions that how the co-founder of KKR, Henry Kravis, donated money to Nikki Haley – a 2024 Republican presidential candidate now serving as U.S ambassador to the U.N. “The head of KKR Middle East is David Petraeus, who was the head of the CIA up until 2012, he was involved with what happened in Iraq, what happened in Afghanistan, so it’s an incredibly problematic parent company to Sónar. […] I’m Iraqi […] so when I learned about that my project became incongruous with Sónar […] I couldn’t even justify playing in any sense.”

Starting in the 2010s, clubbing and electronic music festivals have been increasingly integrated into the capitalist machine — generating over $12 billion in yearly market value in 2024. With the rise of commercial genres like EDM and DJs being the new rock stars, sound system partying is now big business. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that electronic music festivals are seen as a good investment for venture capitalists.

However, the event industry and especially nightlife sectors have been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic era; investors turned to private equity firms to bail them out when their portfolios started to bleed out money. Starting in 2018, the acquisition of essential bits of electronic music infrastructure by large British promoter Superstruct Entertainment opened the door for the real corporate overlords. It was still considered a largely independent world, motivated by passion and curiosity rather than capital.

Superstruct’s portfolio of over 80 international festivals includes Sónar and Boiler Room, the international event platform whose online video series has played an essential role in launching many DJs and producers’ careers, delivering an ersatz club experience into the comfort of one’s home. The pinnacle of private equity encroaching upon these structures was when Superstruct was bought out by KKR in 2024, a large investment group with ties to the building of a large data center in Tel-Aviv suburb Petah Tikva, weapons manufacturing and systemic ecological destruction.

Boycott, Divestment & Sanctions Intensifies in Euro Music Scene

Given the fact that house, techno and their descendants first emerged as the soundtrack of working class, racialized, and often queer people, these music genres and their associated spaces and events tend to still carry a political undertone. Despite most of the discourse around raves and electronic music as acts of resistance being mainly a marketing ploy nowadays, the community still has strong ties with activism and strives to hold its actors to a higher standard. “From my perch [as an artist and cultural critic rather than a music industry professional] it’s apparent that corporate culture is club culture,” says Sivanesan.

“While it seems a lot of people who perform and attend corporate festivals would prefer to unlink partying — hedonism — from politics, I am very interested in the politicization of this sector, as I think there has been a depoliticization of the other cultural sectors I’ve been around, notably contemporary [visual] art. Furthermore, I think it’s worth considering together the corporatization of [club] culture, artistic professionalization and emergent fascisms.”

Sumugan Sivanesan, artist, researcher and fugitive radio host

The BDS movement is modeled after the peaceful protest tactics utilized when fighting apartheid in South Africa. “A boycott is one of the very few more impactful ways for us here in Europe to collectively increase collective pressure from abroad by financially hurting the companies who profit from the genocide and occupation, and thus the Israeli regime,” says Monika Vykoukal, from the Judeo-Bolshevienniks.

The activist group is comprised of “left-wing Jews who live in Vienna,” who strive to enact change through actions such as organizing and emancipatory education while adhering to the principles of feminism, anti-racism, anti-fascism, anti-capitalism and solidarity with other struggles. Their activities include participating in protests, speech and article writing. They are also the only visible Jewish pro-BDS leftist group in Vienna and part of the European Jews for Palestine network.

“A cultural and academic boycott is just as important in terms of tearing down Israeli propaganda and what the BDS movement call ‘normalization’ – the lie that Israel is just like ‘any other’ country, which is cultivated by the participation of clearly state-conforming artists and intellectuals at internationally recognized venues and festivals. The BDS movement has now existed for 20 years. It is a very consistent, well researched and communicated project, and both global and led by Palestinians,” she said.

One of its first notable appearances for BDS in the nightlife world was in 2018, when a white text on a pink square was shared widely by big names in the techno underground. The square read “As long as the Israeli government continues its brutal and sustained oppression of the Palestinian people we respect their call for a boycott of Israel as a means of peaceful protest against the occupation.”

It had real world consequences for Berlin feminist techno collective room4resistance, whose residency at underground club about//:blank was suddenly terminated due to them sharing the square in support of Palestine on September 12, 2018. The club became progressively avoided by artists, partygoers and activists alike, with other resident nights like Buttons severing ties with them. This was one of the first instances when people in the English-speaking club music world — especially Berlin and the UK — faced real-world consequences and loss of income over their support of Palestine.

Things drastically changed with the attacks of October 7 and the escalation of the occupation into war. With the whole world watching, boycotts were seen as the most important tool at people’s disposal for fighting back. Loose nightlife collective Ravers for Palestine has been using their online platform on Instagram since October 27, 2023. Since that date they’ve been constantly reporting on the intersection of nightlife and BDS with concise media, disseminating news articles and creating their own striking infographics.

Before the Sónar boycott campaign, DJs in solidarity with Palestine withdrew en masse from CTM festival in January 2024. Due to its Israeli ownership, others boycotted HÖR, a video platform based in Berlin who rose to popularity post-2020 lockdown filming DJs playing in an iconic white tiled bathroom. BDS supporters called for the boycott for legendary techno club Berghain, an initiative led by international collective DJs Against Apartheid. The club famously de-platformed artists speaking against the occupation; French-Lebanese DJ Arabian Panther said the venue was cancelling his gig after posting on social media in support of Palestine. To this day Berghain has still not met the group’s demands or acknowledge the genocide, despite holding several pro-Ukraine events.

The KKR acquisition also impacted other major festivals such as Field Day in the UK and Flow Festival and Mighty Hoopla alongside, Boiler Room were designated as pressure targets by Ravers for Palestine on February 4, 2025. This is why the Sónar cancellations and boycott represent a key moment in the movement — not just the largest rallying cry, but also one of the most effective instances of artists and nightlife actors taking action. The pressure enacted by these artists led to international coverage in media like The Guardian and Al Jazeera, and forced the festival to issue a statement condemning the genocide and distancing themselves from KKR, as well as offering refunds for ticket holders.

While their media partners and long-time print and online nightlife magazines such as Mixmag, Resident Advisor and DJ Mag framed the new statement as a move in the right direction, running with the quote “We will never send a single Euro to KKR” in their headlines and praising the festival’s accountability, the vast majority of signatories saw this as a veiled attempt at artwashing, offering too little too late in order to save face. In his First Floor newsletter, Barcelona-based journalist Shawn Reynaldo criticized the festival’s position. Shortly after, despite having dropped McDonald’s and Coca-Cola as sponsors, Sónar was added to the official BDS list. Fira, the festival’s main venue, also received pressure from the city’s local council to stop hosting Israeli government pavilions and weapons manufacturers.

“Palestinians, artists and Barcelona-based organizers have patiently engaged Sónar in good faith for more than two months to encourage it to meet the demands that Palestinians have made of all Superstruct-owned events, at a minimum. In this urgent moment of genocide against our people, Palestinians need more than rhetoric. We need the end of complicity, to do no harm.”

BDS official boycott statement

Artist, journalist and educator Peter Kirn also voiced concerns over the KKR acquisition, crediting Ravers for Palestine and Writers Against the War on Gaza (WAWOG) for leading the information campaign. He was set to lead a 4-day workshop called the AI Performance Playground, for which he began preparations in late 2023, including selecting a co-host and applications for participants.

Kirn officially withdrew on May 13, 2025 stating, “We should differentiate between personal ethical choices and boycotts […] Individual choices can be important, but if you want to make a significant impact, collective action has a greater impact. It’s a tactic; you have a goal in mind.” He also noted the involvement of the Wet’suwet’en Land Defenders, who had led opposition to KKR well before nightlife people got involved, due to the firm’s investment in Coastal GasLink. “It’s emblematic of how global finance can drive over indigenous rights,” he said.

Despite the differences in background amongst artists and party goers, the dissemination of this information, initially on Twitter and now mainly on Meta-owned Instagram has not only exacerbated these differences, but also exposed casual party goers to activism. Currently the adherence to BDS guidelines and calls for a boycott from DJs has been a mixed bag.

“Organizing is long-term work,” Vykoukal says. “It is also obviously important to think in terms of the power relationship — organizing in the context of BDS means organizing so there are enough people able to enact a boycott that the festival will have to react, to be a real threat to their bottom line and image.” Especially with BDS, people are asked to take sides, which can be alienating both in their personal and professional lives.

Boycotts are a form of protest sanctioned by international law. Crucially, with last year’s ruling by The International Court of Justice that Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories is against international law, a boycott by our governments of any activity that supports the Israeli settlements would actually be nothing but following that ruling.

“BDS has become almost a slogan, so I can’t speak to how everyone is using it, but the UN engagement on these issues is enshrined in international law and treaties,” Kirn said. “It works both ways. Boycotts are supposed to be protected speech, and you’re also not supposed to target people based on their views or national background. That means, rather than criminalizing BDS, what we should be doing is holding everyone accountable. Boycotts are one of the most essential forms of nonviolent political action.”

Dania Shihab considers that Sónar “is incredibly important in Barcelona and I think even if you ask anyone who has decided to boycott they’re incredibly grateful to the programmers.” She also thinks that the festival is still missing a few other points and that “it’s not adhering to BDS guidelines and seems to have a very weak understanding of what ethical programming and partnerships are.”

Despite media attention towards the cancellations, Sónar reported record attendance numbers and still boasted headliners like Plaid and Modeselektor. Critic and journalist Jessika Khazrik commented on an Instagram reel on the alleged artwashing some of these artists engaged in. She called out the performative nature of some of the support exhibited, describing it as a “genocidal spectacle.” Without directly naming the artists, she shows pictures of famous IDM duo Modesektor projecting the Palestinian flag with the message “Free Palestine,” or another artist turning their set into a lecture-performance with statements like “We are all complicit.”

She also comments on an image of a member of Brazilian group Teto Preto wearing a costume with cut outs around their chest and genitals, a style they’ve worn in other performances, only this time with the Palestinian flag colors. “Some artists have been performing naked while wearing just some stylized elements of the Palestinian flag — I ask you as a feminist; what gives you the right as a Brazilian to do this with an indigenous flag?” Khazrik captions in her reel.

In their statement before the festival, Teto Preto — represented by Futura Artists — emphasize the financial difficulties a group of brown, queer artists from the Global South like themselves are faced with and their choice to go on with the performance. “Being here in Europe, showcasing our work in this formation to the world, is a historic achievement born from a lot of effort — an enormous risk and responsibility as well,” they write. “More than ever, tomorrow we go on stage with our bodies as weapons.”

The contrast between these kinds of superficial acts of support and the actual situation on the ground in Gaza might seem obvious, but for artists like Shihab, it harkens back to real-world, lived experiences and immense trauma. “I was born during a war, the first Gulf War, I’ve lived all my life in the diaspora, I know what suffering looks like, I’m not just seeing it on live streaming. I’m an emergency doctor, I know what blood smells like, I know what burnt skin looks like, I’ve seen amputated limbs.” she says.

While the festival went on as planned, the boycott movement around KKR has been a galvanizing moment in nightlife and the music world at large. Pressure on more targets followed, with new instances of grass-roots, in-person organizing taking on nightlife institutions such as Boiler Room.

Two major groups are growing in scale in California’s Bay Area and New York City dubbed the B.A.S.S. – Bay Area Solidarity Strike and Big Apple Solidarity Strike respectively – that managed to raise over $6,000 for their artists and cancel scheduled Boiler Room events. boycottroom, a movement targeting Boiler Room specifically, was created in July 2025, with the goal of “Uplifting the international call to boycott Boiler Room & all KKR-funded music promotions. Shut it down in every city!” Artists are now asking for their Boiler Room sets to be taken down. Some musicians are also taking their tracks off Spotify.

“What we’re seeing now is the result of this — there are now Boiler Room boycott events scheduled in New York, Detroit, Denver, and other cities.”, activist collective DJs Against Apartheid said. “There have been sustained pressure campaigns in many other places that led to artists pulling out from KKR-owned events. One example is the London-based collective SISU, who pulled out their entire stage from Field Day Festival – including over 30 artists – and organized a counter-event featuring artists who had dropped off the lineup. That’s really powerful because it shows that what we do locally becomes the fuel that inspires further action and solidarity across borders.”

More and more people are getting involved, choosing to fight for the continued existence of the Palestinian people. “Even now, many artists who have recently dropped out from these events have said they weren’t aware of these connections until they were approached,” DJs Against Apartheid say. “That tells us two things: One, that a lot of people are prepared to do the right thing if they have enough information to act; and two, that we need to reckon with the fact that we live in an information bubble, and reaching out to people in our circles in a constructive and non-confrontational way can be extremely effective in shifting the cultural narrative.”

Sivanesan presents his experience in Indonesia as an example, which is by default in support of Palestine, that the BDS movement is not controversial everywhere. “So commercial club culture can also be anti-Zionist,” he says. “Perhaps then, the task is also to look for other points of reference and build connections and solidarity. It’s notable that racialized, trans, queer and artists from the so-called global south have taken the lead on this, so why shouldn’t artists simply divest from Sónar and seek out anti-fascist alternatives and leverage them on the international clubbing scene?”

Cover image: Juliana Huxtable.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.