The City of Salem Told Them They Deserved a Roof Instead of a Tent. Some Ended Up With Neither.

Salem, MA — Two winters ago, Maria Nolasco moved into a sprawling homeless encampment in Salem, Massachusetts for seven months. Though there wasn’t much order or respect — and many didn’t like the small, 45-year-old Dominican woman — she liked her little tent.

“We called it houses because that was home,” Maria said. When she first arrived, there had been just a couple houses. She had watched Tent City, as locals coined it, grow into a community. But it didn’t last long.

On June 26, 2024, local police and public service workers removed Maria’s tent, along with over twenty other tents that at one point housed at least forty of Salem’s homeless. Following extensive police pressure, most residents had already left, some to the woods — where many still are to this day — or to other more discreet locations. But not Maria. She had stayed to the bitter end. From her still-standing tent’s couch, she took drags from a cigarette as she watched bulldozers tear up all those little houses, knowing hers was next. Losing her tent was a pain worse than losing her apartment, the sleep-deprived, reddish-grey haired woman with defined black bags under her eyes told me.

“I was making sure that everybody was out,” she said, “Me? I was happy there.”

Maria’s tent was filled with the belongings she had kept since she’d been evicted. She lost them when her tent was swept and hasn’t seen them since, but that outcome didn’t surprise her. Maria was one of over 29,000 homeless individuals in Massachusetts last year, which represents an over 50% increase from the year before and the fifth highest individual count in the country.

“We’re nobody,” she said, “The homeless people are nobody. Worse than a trash barrel. That’s how they see us.”

Like cities and towns across the nation, Salem had developed its very own homeless encampment problem. State and local officials have long held Massachusetts, just as much of the rest of the country, is in an affordable housing crisis (it is estimated about 440,000 units short). More than 30% of renter households in the state are estimated to be extremely low income, and Salem’s cost of living is estimated to be 1.5 times the national average.

“Some people might have mental health issues, they don’t want to be on the streets, people with addictions are also not wanting to be put on the streets,” said Robyn Frost, executive director of the Massachusetts Coalition for the Homeless. “Having said that, there is no places for people to go. All the shelter spaces are full, and it does force people to make the most difficult choice of living on the streets.”

Hear Maria in her own words:

A National Discourse at Home

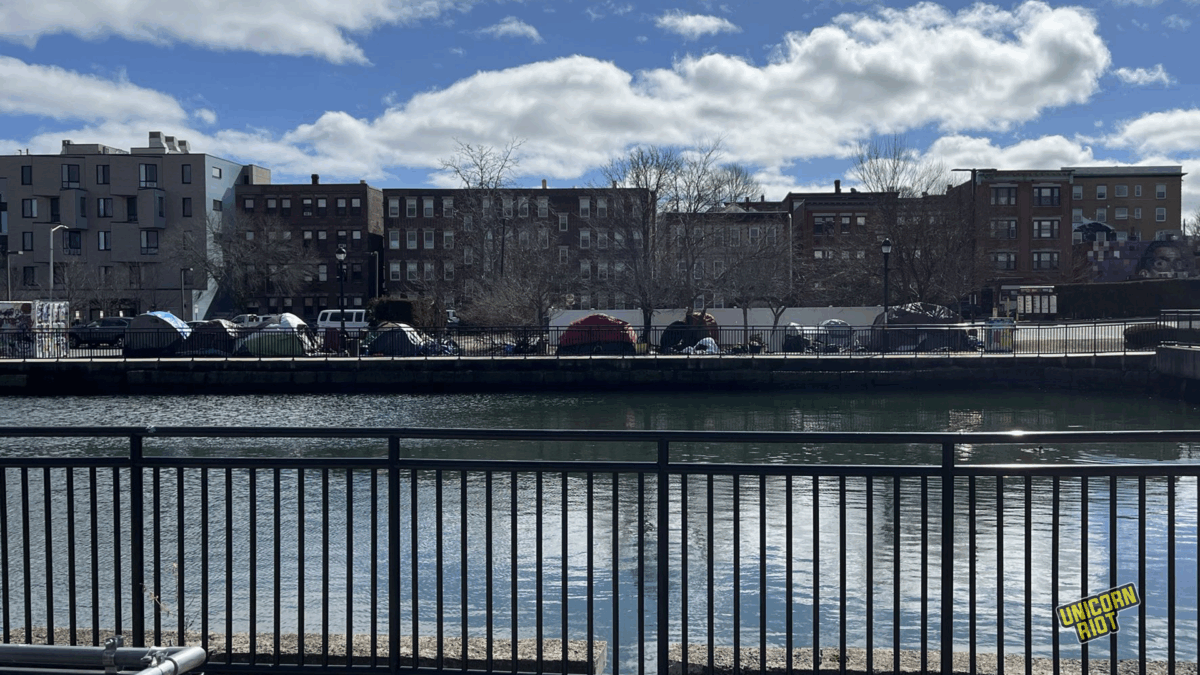

The encampment formed in the early summer of 2023. A year later, it spanned nearly the entire footpath residents regularly use to stroll the city’s South River downtown, which extends more than 1000 feet. It began with a long, single-file line of multicolored tents against a black fence along the path. If you continued down it, the line formed into a bustling center of about a dozen-and-a-half more tents filling out a wide section of city-owned land between a busy Wendy’s drive-thru and a playground.

Pretty soon after it had begun, trash started to build up. By the time it was swept, dozens of opened and closed garbage bags spilled over the campsite, surrounded by different pools of water. When it rained, the river would rise over the walkway and the tents would flood, the water mixing with loose trash.

The mess attracted rodents. “Imagine,” Maria told me, “You in the street already. Then, you living in a trash barrel with mice.”

Meanwhile, residents railed against Tent City. “We’ve put up with it for too long, and it’s out of control,” a man who lived across the street from the encampment told Boston.com, encapsulating the thoughts of many. “I’m out of patience. It’s ridiculous. I’m sure people will call us callous, but they don’t have to live with it everyday.”

Numerous residents felt the encampment was dangerous. After all, it had been the cause of 203 emergency calls, including 49 trespasses at Wendy’s, two fires, and at least four assaults by April 2024.

The pressure was beginning to mount on Salem Mayor Dominick Pangallo. Elected May 2023 — around the same time Tent City first popped up — the new mayor began facing calls to do something about the encampment soon after his inauguration.

A few months later, in October 2023, similar calls forced Boston Mayor Michelle Wu to sign an anti-camping ordinance targeting a notorious encampment in her city’s South End. The ordinance barred tents on public property if shelter was available.

Although many in Boston had long pushed for the encampment’s removal, others raised concerns. How could the city possibly ban homeless people from having a tent? Advocates and residents argued sweeps make homelessness a crime, displace people, and are not evidence-based. Though most agree more research needs to be done, studies show encampment sweeps don’t effectively reduce crime and may “substantially increase drug-related morbidity and mortality.”

A small coastal city 15 miles north of Boston that has a median household income of over $80,000, Salem wasn’t used to this type of homelessness. It wasn’t like Boston or the neighboring Lynn, where visible street homelessness and encampments had long been commonplace.

During the Halloween season, Salem’s grim history regarding the infamous witch trials of 1692 brings in hundreds of thousands of tourists — and their dollars — to the so-called ‘Witch City.’ In October 2023, though the city’s population consistently hovers a little above 40,000, it saw 1.2 million tourists, a record at the time. And a lot of them had seen Tent City. City officials often claimed the encampment had a negative effect on local business. While there are no available numbers for how much money tourism generated Salem in 2023, the city still generated $140 million the year before despite reporting 200,000 fewer tourists in 2022 than 2023.

Everyone in Salem — both housed and unhoused — agreed something needed to be done about Tent City. But they would come to find they had very differing ideas on what. On March 14, 2024, at a Salem City Council meeting, Pangallo proposed Salem’s very own anti-camping ordinance for city-owned land.

Though her tent being swept may have been the worst time Maria had lost everything, it certainly wasn’t the first. Her family lost their longtime Salem home after COVID temporarily left Maria’s son unable to work. She wasn’t working for mental health reasons. Twenty-five years ago, her daughter’s father Kramo Curry died of a heart attack after he was stabbed twice in a Salem parking lot. After he had managed to make it back to their apartment, a very pregnant Maria drove him to the hospital. He checked himself out a few days later, but his heart sac had not had time to fully repair itself.

The day after Curry was murdered, Maria gave birth to her only daughter and developed postpartum depression. It’s been hard to hold a job since.

“I’m still looking for me. I lost myself. Having my daughter’s father killed, and then having my daughter the next day,” Maria said, “It’s like yesterday. I’m still with him. Mentally, I’m in a bubble. I don’t really feel–can you understand what I’m trying to say? I have trauma.”

In 2023, Maria was evicted from the Section 8 apartment where she had lived with her four children for more than 20 years. Maria’s kids went to go stay with her sister. But her sister’s apartment was too small for her to fit.

For the first time in her life, Maria was homeless.

The first place she went was Lifebridge North Shore, the city’s sole homeless shelter. But like most who would eventually move to the encampment, she couldn’t get a bed there. So, she moved to the infamous Tent City on Salem’s South River Harbor Walk, less than a mile from her old apartment.

‘A tent is not a roof’

On March 27, 2024, the city’s Public Health, Safety, and Environment Committee held a vote to pass Pangallo’s anti-camping ordinance to the city council. Local organizations that provide services to the encampment — Witch City Action (WCA) and Salem Survival Program (SSP) — organized dozens of residents to speak out against it. The tense meeting was a microcosm of a national debate that was taking place in municipalities across the country — encampment sweeps or no encampment sweeps.

Mayor Pangallo gave the opening remarks.

“Our goal is direct: to get people into housing,” Pangallo told a packed chamber at Salem’s City Hall, “Everyone in Salem deserves a roof over their head. And a tent is not a roof.”

People call Maria tough. Her refuge had stood on the city-owned land the entire seven months she’d been at Tent City. She agreed it wasn’t an ideal place to live. She told me she didn’t do drugs at the tents, saying the constant use from her encampment neighbors often drove her crazy. She wanted to live like a human, and when at the tents, she told me she encouraged her peers to also live like humans, which didn’t always prove itself a welcome critique. People didn’t get along with Maria. She had gotten into many fights in her time at Tent City, she told me, for how she talked, dressed, and carried herself. But she never wanted a sweep.

“So you don’t want us here.” Maria said. The idea seemed silly to her. “And you want people to get better? You’re putting us on the streets.”

Similar to Boston’s ordinance, Salem’s ordinance does not allow police to sweep homeless encampments from public property unless there is available shelter. But as WCA and SSP organizers Skyler Clark and Caitlin Tricomi pointed out, unlike Boston, Salem’s ordinance considers available shelter anything “within 15 miles from the nearest border of Salem,” not just Salem proper. And even if it did, a shelter bed was not a reliable roof. On top of that, despite the city’s flowery language surrounding housing and shelter, they didn’t believe the city was actually interested in helping the homeless after how they had handled — or not handled — the trash build-up at the encampment.

“The city escalated things by removing trash cans instead of focusing on ways they could make it safer for people,” Tricomi said. “The city created the unsafe conditions, they are at fault for this, and they need to take responsibility.” Clark told me the city would cite biohazardous materials such as used needles for the removal of the trash cans and the lack of pick-up.

“Every time I was doing trash pick-up there were no needles,” Clark said, explaining that the local needle exchange would come to the encampment twice a week to pick up used syringes, “I think I saw a needle maybe once, throughout all of the time I was doing trash there.”

“They always was complaining about trash,” Maria concurred. “But the city never picked it up.”

No matter how many needles were actually on the ground, Salem police said they had responded to at least 11 overdoses at Tent City. Residents said to add a zero to that number, and maybe it would come close to the real amount.

Ashley, who preferred to use only her first name, has been homeless for almost two years. Having been in-and-out of the area all her life, the 38-year old stayed at the South River encampment multiple times. Many people she knows and loves used injection drugs there, including her boyfriend, another former Tent City mainstay.

When she and her boyfriend stayed at the encampment, they saw the local needle exchange twice a week on Mondays and Fridays. Now, sleeping outside in different places every night, they are lucky to see them once a month. Needle exchanges commonly distribute Narcan, a brand of a life-saving drug called naloxone that reverses opioid overdoses.

“I must have Narcan’d 35 people in a year,” Ashley said of her time at Tent City, “I don’t personally shoot, but I’ve always picked up [clean] syringes in case somebody is in need. I do that less now. It’s frustrating ‘cause it puts a lot of worry on the people that love the active users.”

A community that uses injection drugs living in an active encampment sees less overdose deaths than the same community after it undergoes an encampment sweep. Studies show someone considered to be chronically homeless costs taxpayers an average of over $35,000 a year. But a community using injection drugs living in an active homeless encampment is also less expensive to the average taxpayer than if the same community undergoes an encampment sweep. While a housing-first approach — offering housing and services with no strings attached — is the most expensive, it saves by far the most lives. The worst approach, according to a soon-to-be-published simulated modeling analysis from Boston Medical Center, is a sweep with no offer of supportive housing at all.

“More deaths, substantially more cost – not more than housing, but more than status quo – less people on [medications for opioid use disorder], less time in housing,” Hana Zwick, the study’s head research analyst said, “All of the outcomes aside from cost were the worst of all of the strategies that we ran, and cost was higher than status quo.”

Though local politicians and residents alike may have truly wanted what’s best for residents at the encampment, Zwick said the method Salem chose — a sweep offering shelter and no supportive housing — wasn’t even something her team bothered to model for the study.

“We were trying to model things that we thought would be productive,” she said, “We did not think that the shelters would be productive because of the way that the shelters are.”

Maria had long tried for a bed at Lifebridge. But a lack of shelter space had forced her to the encampment in the first place. To address this, Lifebridge — in collaboration with the city — opened a new low-threshold overflow shelter just days after the March 27 committee meeting with the hopes of targeting Tent City residents.

A little more than a month later on May 9, 2024, Salem’s City Council passed the anti-camping ordinance in a 10-1 vote. About a month after that on June 8, local organizers sounded the alarm. Police had told Tent City to expect a dispersal order June 17. As organizers did their regular Saturday distribution to the encampment June 15, they were surprised by bright orange dispersal orders hanging on every tent. They had been posted two days prior.

The ordinance gave encampment residents seventy-two hours to vacate from the time the order was posted, meaning when organizers finally learned of the orders that Saturday, anyone left would’ve needed to be gone the next day. But it had a catch. As required by the law, the city was to maintain a list of all available shelter spaces within fifteen miles on its website. The list was to be updated daily, but the city had yet to make anything of the sort.

Local organizers got lawyers involved, and the city had to put off the sweep. But days later, new dispersal orders were back on the remaining tents. The city had posted their version of the list.

“They published a notice on the Salem website, and it is one entry long, and it says Lifebridge Transition Center,” Clark said. It wasn’t updated daily either. The singular entry offering Lifebridge’s phone number still remains on the city’s site at the time of this article’s publication, unchanged since it was first posted June 18, 2024.

“That’s technically not legal, but whatever,” Clark remarked.

A Bed at the Shelter

“They didn’t have no beds for all of us,” Maria told me, “They opened the overflow because they was planning to destroy Tent City, right? But guess what. It was a lie.”

A month after the sweep, she’d finally received a bed at a Lifebridge shelter. But her belongings would not join her. When her tent was swept, Salem police had not come with anything to store Maria’s things. Despite the chief of police being required to establish a storage policy for swept residents’ belongings, a public records request revealed that the Salem Chief of Police Lucas Miller issued the city’s first-ever storage policy on July 1, 2024, five days after the South River encampment had already been swept.

Salem police did not respond to a request for comment regarding why this decision was made.

In lieu of a legally-required storage policy from police, as well as a place to go, her things ended up in the hands of Salem Survival Program organizers on the scene that day, where they still are.

It’s not that she doesn’t want them back. She just has nowhere to keep them. By the end of the summer last year, Maria told me she’d received a lifetime ban from Lifebridge services for being guilty-by-association. The men she hung around were accused of selling drugs by shelter staff, and after a heated exchange with a staff member, she had not tried to go back. Since then, she’s been sleeping in different places every night. Her latest spot is in a parking lot, just feet away from the doors of Lifebridge’s day center.

Like many shelters, Lifebridge has been said to have restrictions such as curfews, mandatory chores, and certain sobriety requirements. They have also been accused by local organizers such as Clark, as well as Salem’s unhoused population, of being hostile with participants, quick and inconsistent with suspensions, and unforthcoming surrounding policies and procedures.

Lifebridge President Jason Etheridge and Vice President Gary Barrett did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding these allegations.

Ashley, for example, told me she was banned for life from all three Salem-based Lifebridge shelters. It was also because of a dispute she had with a staff member, she said, though the details of it were unclear. In the past, Ashley said she had received a thirty-day ban for “flipping off the director” but this time, they were giving out no-trespasses instead of bans.

As Ashley explained, the two types of suspensions Lifebridge handed out were no-trespasses and bans. The no-trespass orders are more serious and legally enforceable, potentially involving the police. A ban, however, is enforced solely by the shelter.

The opaqueness of this process has made it unclear which clients are actually banned or not in conversations with the shelter, Clark said. “That was their logic. Since no one really has a no-trespassing, or a very few people, that means no one is banned, when we know for a fact that they are banning people constantly because they’ll go into Lifebridge and they’ll be like, ‘You’re banned, get out.’”

That’s what happened to Ashley. One day, to her surprise, she got to the overflow shelter and was told to get out.

Even if Maria and Ashley had been allowed a bed at the overflow, it’s unclear if they’d have been able to keep it. Exactly a year after it opened on April 1, the overflow shelter was cut to 25 beds, citing a loss of American Rescue Plan Act funding. But they should have known better, Clark said.

“We kept trying to explain that we cannot just pass this ordinance thinking [the overflow] is going to be the solution to our bed availability problem, because it’s going to fill up,” she said, “And that’s exactly what happened.”

‘Where are we gonna go?’

A few months ago on April 10, Mayor Pangallo proposed an amendment to the anti-camping ordinance. Instead of seventy-two hours to move all their belongings after a dispersal order, encampment residents would now have twelve. And the list of available shelter space would officially no longer be updated daily (though it never was). The proposal would also remove guarantees that the city assure these shelter spaces exist for a “reasonable period of time.” That language, Pangallo wrote, was too open-ended. About a month ago, the amendment passed the city council.

Mayor Pangallo did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. In response to a set of emailed questions regarding the content of this story, Salem City Hall office director Sabrina Trask said, “The city will not be responding to your questions at this time.”

Many of Maria’s peers would get a temporary bed at the overflow shelter following the sweep, but many would not. Those who were left without beds—many either shelter-resistant or banned—took their chances outside. Some ended up in rehab or detox, or jail. Some died. In late April, Salem police made an arrest after two men living in the woods were found stabbed to death. If you walk around Salem today, though there are many more new faces on the street, you may see a few of the former regulars of Tent City, like Maria or Ashley. But you won’t see a tent.

“We are the people,” Maria said, “Where are we gonna go?”

Maria didn’t disagree with Pangallo on one thing: a tent was not a roof. But neither was the sky.

“I’m gonna get a little reunion with some of them that will stand with me,” she said, “And I think we are gonna set up Tent City again.”

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: