Strike Captain Interview: Philly’s DC 33 Union to Vote on Agreement to End Historic Work Stoppage

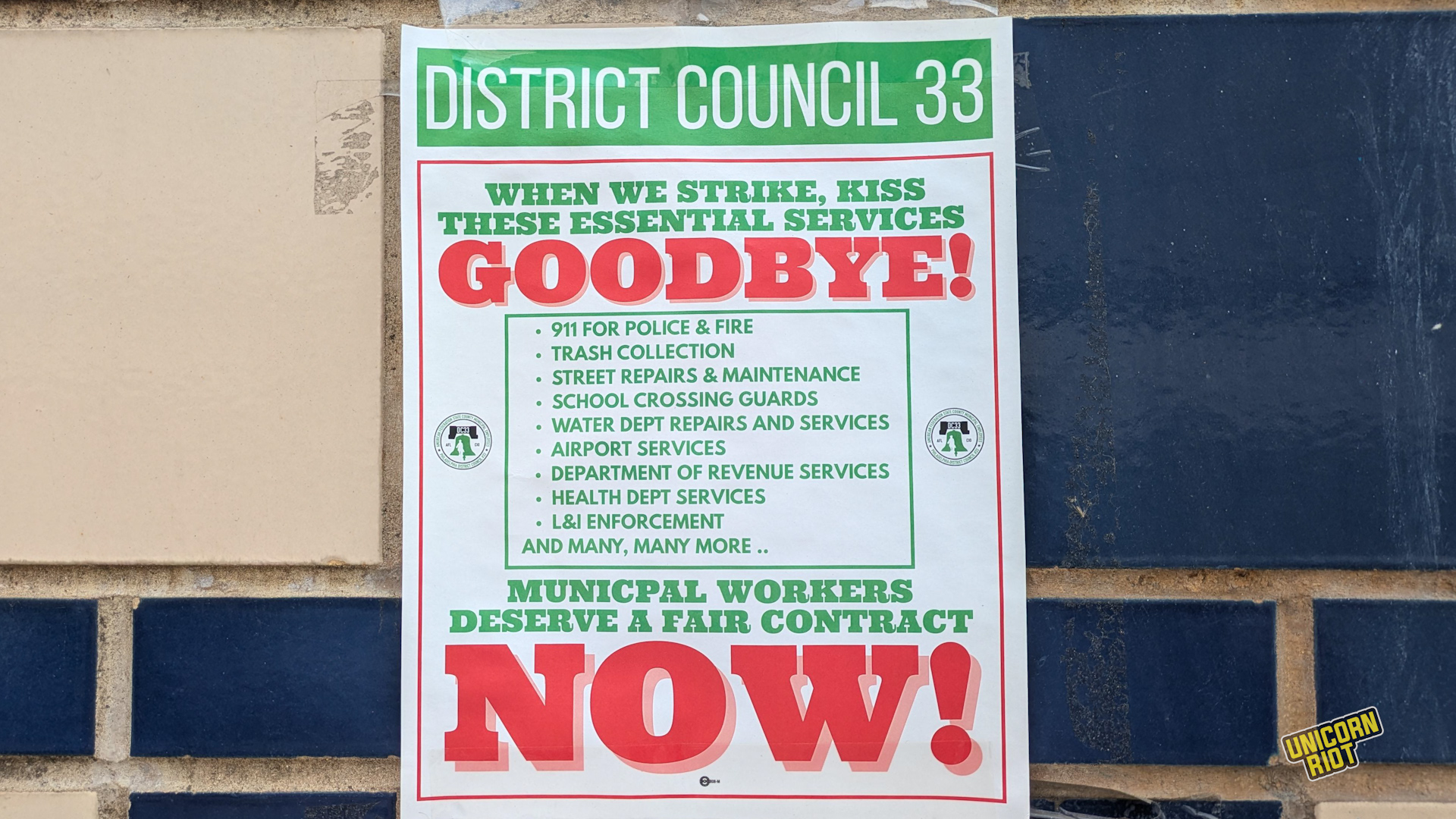

Philadelphia, PA — American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) District Council 33 (DC 33), the city’s largest blue-collar union, launched a historic strike earlier this month, halting sanitation services on a scale not seen since 1986. Despite the pro-union image Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker wishes to project, legal injunctions were used to force many city employees back to work – creating pressure to end the strike.

“The city was trying to pick us apart with injunctions all over the place,” requiring water department employees, 911 dispatchers, and city medical examiners to return to work immediately, DC 33 President Greg Boulware explained in a recent interview.

After reports of alleged sabotage and confrontations with scabs (non-union workers hired to replace strikers), another court order demanded a stop to “unlawful activity” at picket lines, but included additional stipulations such as limiting pickets to 8 workers and requiring pickets to stay 10 feet away from entrances. With weaponized judicial pressure mounting, on the early morning of July 9, DC 33 reached a tentative three-year agreement with the city of Philadelphia that ended the eight-day strike.

“You can’t claim to be pro-labor, pro-union, pro-worker and then not make steps to do things that would change the economic status to do things,” said Boulware.

“The Mayor also tried to connect the housing initiative [a public benefit designed for ‘low-wage workers, under-employed or unemployed, municipal and union workers…’] to our membership, which had nothing to do with it at all. If you have a program in place try to get poor folks into housing, once they’re in that housing they have to afford to live in that housing…”

DC 33 President Greg Boulware

Sanitation workers in Philadelphia earn the lowest salary of any major city in the US. According to the MIT living wage calculator, the current average salary of a DC 33 member is more than $2,000 below the wage needed for a single adult without children to live in the city. For a family with one child, the living wage gap nearly doubles. One worker on the picket line said she couldn’t afford to buy diapers on her current salary. Depending on family size, the average city worker may be eligible for public assistance.

As garbage collection returns to its regular schedule this week, DC 33 members have until Sunday, July 20, to vote to accept the new agreement, or reject it – which may lead to a second strike authorization process. Many striking workers demanded no less than a 5% increase in their current pay, down from the 8% annual increase DC 33 initially proposed in negotiations. The tentative agreement only offers a 3% increase year-over-year, not far from the city’s original offer that led to the strike in the first place. The union vote will be announced on Monday, July 21.

Despite the anti-union tactics and lawfare by the city, many strikers stood true to their purpose of trying to win better economic treatment on the picket line. Unicorn Riot was able to speak with one DC 33 ‘Strike Captain,’ an unofficial point person informally designated by the union, about where things are potentially headed and how the strike went down. This interview was conducted on the condition of anonymity and represents their individual perspective and experience.

Unicorn Riot: How did DC 33 union members react to the announcement of the tentative agreement reached with Mayor Parker’s administration to end the strike, considering the terms were far below many of the strikers’ demands?

Anonymous DC 33 Worker: A lot of people are like, “What happened in there?” Because from a lot of picket lines it looked like we were doing OK. People could see the rotting trash getting worse and the understanding was that with more time, we had more leverage.

Even though people were missing paychecks, what I’ve heard from coworkers across the board is that if we were already striking, we should’ve waited longer. They don’t really understand what happened.

I don’t hear a lot of talk that [DC 33 President] Greg Boulware sold us out or anything. I have heard people say it’s suspicious that the AFSCME national President [Lee Saunders] sat down at the table with them the day that we folded.

I’ve heard that we should’ve struck for longer. People just don’t really understand how we went from guns blazing to folding immediately.

There’s a lot of questions about what a ‘No’ vote would look like. It’s hard, because the issue is that things are not really structurally coordinated, so even the idea that we would purposely try to track like, “OK, here’s our membership and let’s try to talk to everybody about whether they’re asking to vote ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ or just to get out the vote” is not intuitive, I’m finding, even though it’s like, to me, kind of what labor organizing is.

At this point, enough [DC 33 members] are individually pissed that the majority of the people who show up might vote ‘No.’ The majority of the people who show up probably won’t be a majority of the union. So if the issue is that people weren’t showing up to strike, having a majority of a minority vote ‘No’ doesn’t solve that problem. The way I’m talking about it with people is, you certainly should vote to show that people are engaged in the union on this.

I’m personally not in support of any kind of coordinated “Vote No” campaign unless it has an ask associated with it. If we wanna do a coordinated “vote ‘No’ until we see this very specific possibly winnable clause added,” then that would be one thing. But I’m wary of the idea of “just vote no,” because I think our leadership tried to get the best they could. Like, I do kind of believe that Greg Boulware got the best he could under the circumstances from where he was sitting and could see everything. So I hesitate to be like, yeah, vote no and that will suddenly mean we have all this leverage. If it wasn’t there, it wasn’t there.

There’s a lot of confusion and misunderstanding about what things trigger what actions. A lot of people saw the letter saying that the [DC 33] local Presidents, the executive board, had voted to send this Tentative Agreement to the membership. And they were like, “oh, do we not get to vote then?” And it’s like no, that’s who voted to end the strike, that’s not the vote [to ratify the tentative agreement].

UR: The tentative agreement (TA) isn’t ratified until you all vote, right?

DC 33 Worker: Yeah, but a lot of folks just saw that and thought, “oh, every local voted and so that’s done now.” So there’s a lot of talking to people about that. I’m not saying they don’t understand, but they are not receiving any information about how this stuff works.

UR: One thing that was somewhat unique about this strike was the amount of intersectional movement support that we don’t always see with Philly unions. For instance, the Sunrise Movement staging a sit-in at City Hall supporting the workers’ demands is not something we typically see in other municipal services or other strikes in Philadelphia. Why do you think that is?

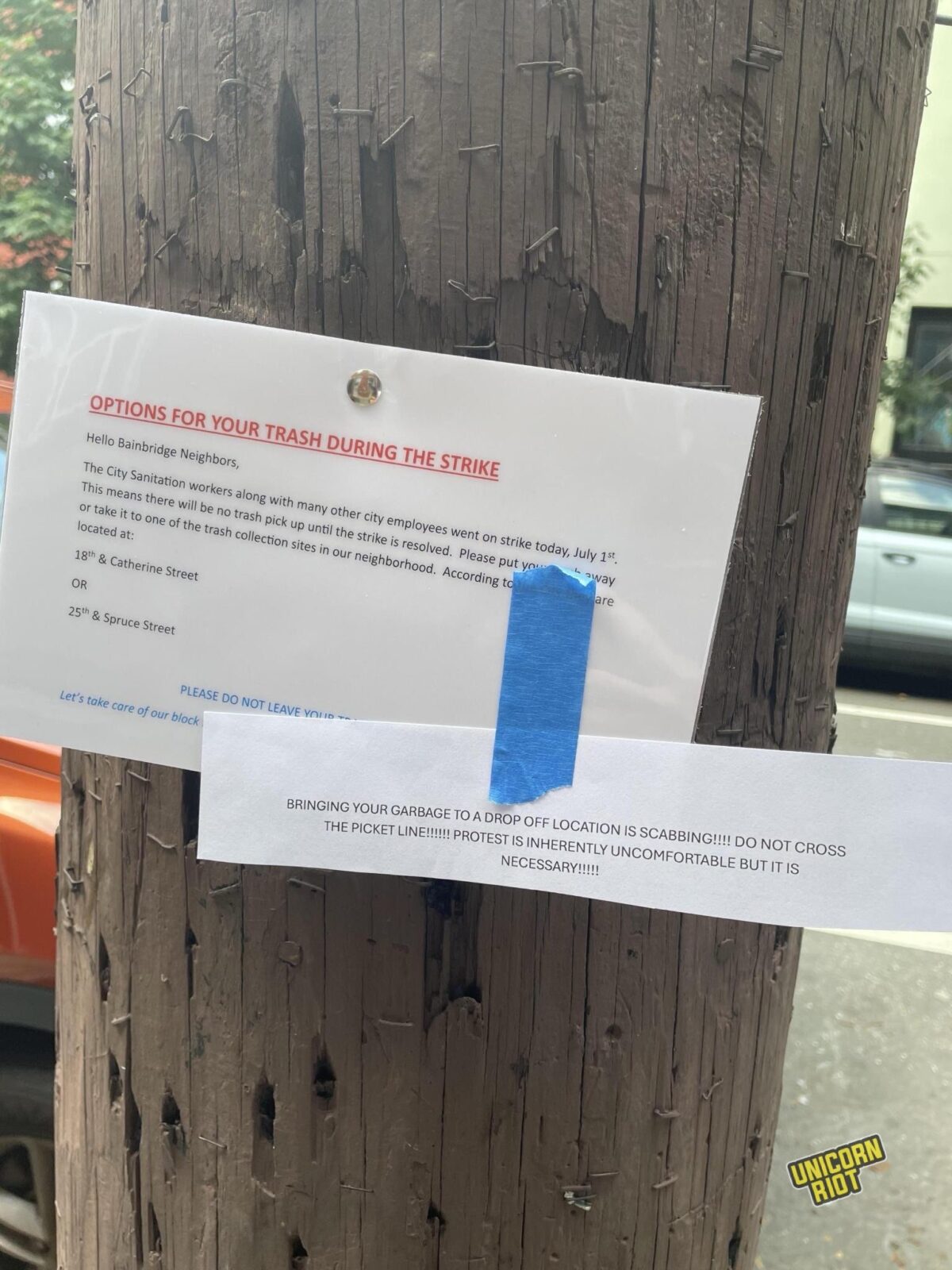

DC 33 Worker: Municipal strikes, and public sector strikes in general, depend upon public opinion. We could’ve done more with public opinion. Ideally there would’ve been more flyering, more encouraging people to co-worker-organize themselves by talking to their own social networks and getting their churches and community groups on board with the strike.

DC 33 Worker: I appreciate that community groups with less organic connections to us stepped up to do tactics that the union technically could not do. I can’t do certain behaviors without risking getting my own picket line and all the picket lines further injunctioned. But if the people of Philadelphia feel so inclined, then that’s their business.

UR: How do you see the DC 33 strike within the larger context of racial injustice, extreme poverty, and economic inequality in Philadelphia?

DC 33 Worker: One of the reasons we were able to come out with the force that we did – even while some chunks of the union did not have the same level of organization as others – is that historically DC 33 workers don’t make enough money to send their kids to college, and so the best jobs they can get are in DC 33, so there are these tight inter-generational networks within DC 33.

DC 33 Worker: It’s hard to live in Philly for more than a few years and not know somebody in DC 33, or be related to someone in DC 33 in some way. That’s one of the reasons there was such a staunch “we do not cross picket lines” feeling inside the union and in the city going into this.

I see a lot of people online saying, “oh, they folded because people are running out of money.” But people in a tough financial situation are often still sharp enough in their political development to understand when something is worth their while even if it’s going to cost something in the short term. I didn’t hear of anybody crossing [a picket line] because they were running out of money and thought that they financially needed to scab.

UR: Other than the injunctions and the city bringing in scabs (non-union workers) to do strikers’ jobs, what challenges did you see facing the strike?

DC 33 Worker: The biggest thing would be the chunk of [union] people who decided to stay home instead of show up and picket, we’re more concerned about that than people who potentially crossed [a picket line]. But that’s a question of, like, how do you build power in unions in between strikes? That was never gonna just come together.

UR: Moving forward, what you said about, if people decide to vote ‘No’ there should be a specific demand, what do you see happening? Does it sound like people would overwhelmingly vote ‘No,’ or does it sound mixed?

DC 33 Worker: I haven’t talked to anybody who is thrilled about this and wants to vote ‘Yes.’ I hear people who are not convinced a ‘No’ vote would do anything and so may not show up or may show up and vote ‘Yes’. I’m not hearing people who feel good about this or are excited about this.

DC 33 Worker: I don’t think – short of having a second historic strike – that we’re gonna come out with a drastically different contract than we have now, even with a ‘No’ vote. If there’s any internal organizing that happens, I would hope that it would be responsible about inoculating people about what is and isn’t possible from here, so that people don’t get even more disappointed with things. More than anything, we don’t want people to swear off union politics for good. That’s not going to get us the contract that we want next time.

So I’m concerned about that when people talk about ‘No’ campaigns. But when it comes to individuals voting, I’m gonna vote ‘No’ because I was very specific with myself and my coworkers about what our red lines were, what contract am I out here fighting for? I personally really wanted to see the lower wage classes abolished. Out of the things in our original proposal, that was something that was financially not that expensive to do and would have raised the bottom, which is what I was out there for.

DC 33 Worker: But I do think that long-term, that kind of “every individual decide to show up and vote if you want to” attitude is not gonna be sufficient for building rank-and-file power that can win a strike like this. I’m not confident that the number of people who show up and vote at all – ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ – will be any kind of majority of the union. If you get a minority of the union to show up and vote ‘No’ and that ‘No’ vote wins, that doesn’t mean that the power is there to execute a second strike.

There’s a good chance that the people who decide to show up in person to the union hall and vote at all will be the kind of people who want to vote ‘No.’ But I’m not sure what that will mean for the negotiation table that Greg Boulware and the [DC 33 Executive Board] will be returning to.

UR: Does a ‘No’ vote automatically mean the strike is back on?

DC 33 Worker: No. Just because there’s a ‘No’ vote, it doesn’t mean we go back on strike. Our strike vote that authorized the strike we just had is still in play. We wouldn’t have to re-authorize a strike. But just because we say no to this contract doesn’t automatically mean we will be on strike, in the same way that anytime they’re in the negotiating room, it doesn’t mean we are automatically on strike.

The union [leadership] would still have to authorize the second strike. [If they did], that forces everyone back to the negotiating table. And maybe the threat of striking again is something that’s in play. Certainly the membership would have a couple more paychecks to get us through – I’m at work right now getting paid – and by then I don’t think the entire backlog of problems on the streets, with all the streetlights out, will be cleaned up.

DC 33 Worker: So it’s not like we’ll be starting from scratch. It really depends on who shows up to vote, but if a low enough percentage of people show up to vote, that goes to show that people are probably not gonna be ready to strike a second time.

That’s all hypothetical. I personally think what will happen is a smaller percentage of the union will show up to vote, and those folks will be close to a ‘No’ if not definitely a ‘No.’ And that’ll be that and they’ll have to go back [to the table], but the leverage in that situation is a little unclear compared to the last time, other than the Mayor having the option to say, “OK, I have to give DC 33 something that the membership will ratify.” It’s not clear what those concessions would look like.

We might have gotten all that we can get. I personally think we could’ve struck longer and it would be a different situation.

UR: You said that DC 33 President Greg Boulware probably got the best deal possible given the circumstances. Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker used the judiciary to essentially nullify workers’ right to strike by asking judges to order the water department and the 911 dispatchers back to work really quickly. And then after 8 days, bringing the sanitation workers back with an injunction, or the threat of it, seemed to act as leverage for the city to use to stop the strike, which is a pretty stark contrast to the last strike in 1986 where it took 20 days for the city to bring that injunction.

UR: Can the union use the law to defend the right to strike? It seemed like they were stuck between a rock and a hard place, overpowered by the local judiciary. Do you have any insight into all that?

DC 33 Worker:

I don’t think that there is a legal framework to have rebuffed those [injunctions] in the course they ended up in, but I don’t understand why they didn’t have more of a plan for preempting and responding to those injunctions when they happened.

It’s true that once we strike, the injunctions are coming. It’s also true that, well, it’s not like I show up to work having been injunctioned ready to pick up maggots off the street doing my best job with a historically gigantic backlog, you know. Even injunctioned workers can do work slowdowns. There’s still all these levers that are available. Even if certain people get injunctioned, there’s still plenty of ways to continue to strike. Most unions that strike at this point are not doing true work stoppage strikes the way that we did, so there is a whole playbook there.

I think the fact that they were not prepared with a game plan for those injunctions speaks to how ill-prepared they were to strike.

Given the circumstances, they maybe did get the best contract they could. But the circumstances were that they started planning for that strike a week before it happened. I know this as a rank-and-file member who was ready to step up and strike. I had been asking for six months, “can we please start making a plan for these pickets in case we need them?” and I did not get the go-ahead or the assignment that I even would be a strike captain, or where my location would be, until the Thursday before the Tuesday that we struck.

So if there’s a criticism of the union, I hesitate to locate it in the negotiation room. A lot of newer folks have found it really difficult to get any information or to participate at all. I’ve been really blocked in a lot of ways in my local.

I think it means something that the Presidents on the [DC 33 Executive Board] who did try to vote ‘No’ on this contract are the Presidents of the locals that have larger participation and have been planning for this for months and were ready to go last year when we almost struck. It’s not a coincidence that the [DC 33 local] Presidents who voted to stop the strike were the ones who didn’t prep for it in any meaningful way.

That’s why I feel that under the circumstances, it was an excellent strike for having been kinda seat of the pants. I’m not sure that they could’ve gotten more given the circumstances.

UR: I did see in an interview with DC 33 President Greg Boulware that he said the Water Department injunction came out like 30 seconds after the call to strike. It seemed that the Mayor’s administration was already prepared and aligned, coordinated with the local judiciary to get that out right away?

DC 33 Worker: Yeah, and [DC 33] should’ve internally had a contingency plan for that. When we started talking about striking a year ago, there should’ve been a plan for “OK, when the injunction happens, how do we behave?” If you had a base of strikers trying to strike, who understood how to respond to those situations that were basically inevitable (even in ’86 they did get an injunction eventually), you have to have a plan for what to do when that happens. It’s obvious that there’s gonna be some injunction at some point. The plan couldn’t have been to just fold as soon as it happened and let the Mayor dictate the timeline for that.

Before the tentative agreement was reached in the #DC33 municipal worker strike in Philadelphia, library administrators were sending emails encouraging employees to call the police on strikers: pic.twitter.com/AfhmJuYFCb

— UNICORN RIOT (@UR_Ninja) July 10, 2025

UR: Another union member shared an image from the city that seemed to say shouting at scabs wasn’t allowed, as part of the injunction?

DC 33 Worker: Yeah, I saw that image too. They sent it out, but I simply disagree, and luckily I am in a union. So if they try any kind of disciplinary action towards the strikers, I mean, I know a girl who threw a hot bowl of soup at her boss and she didn’t get fired. Obviously striking is different and there’s political reasons to come after us, but I’m pretty confident I’ll be OK.

DC 33 is really good at this 1980s to early 2000s union mindset of “holding onto what we’ve got.” That includes not letting anybody get fired – we will not let ANYONE get fired. They’re very good at holding onto shops that are organized, but they’re not necessarily noticing when things get contracted out to nonprofits or whatever.

That post-Reagan defensive mindset was necessary to survive the general dismantling of organized labor in this country. One new thing we’ve learned in the last months is that now there is energy for a more offensive approach.

UR: It seemed that, at least in the beginning, there were a lot of things outside the scope of what would be legally tolerated in a strike, people kind of pushing the envelope on their own, not under union guidance, working to hold the line at pickets in whatever way they could.

DC 33 Worker: Totally. And I think that’s a really beautiful thing about this strike. Even though it has gone the way it has gone, what we need in the labor movement is these big swings for the fences. And even if it means that when we threaten to strike next contract, both sides have a clear idea of what kind of power was available this time, there is something nice about knowing just what that looks like when we make decisions going forward. I hope that it doesn’t cause us to be more conservative in the future towards striking.

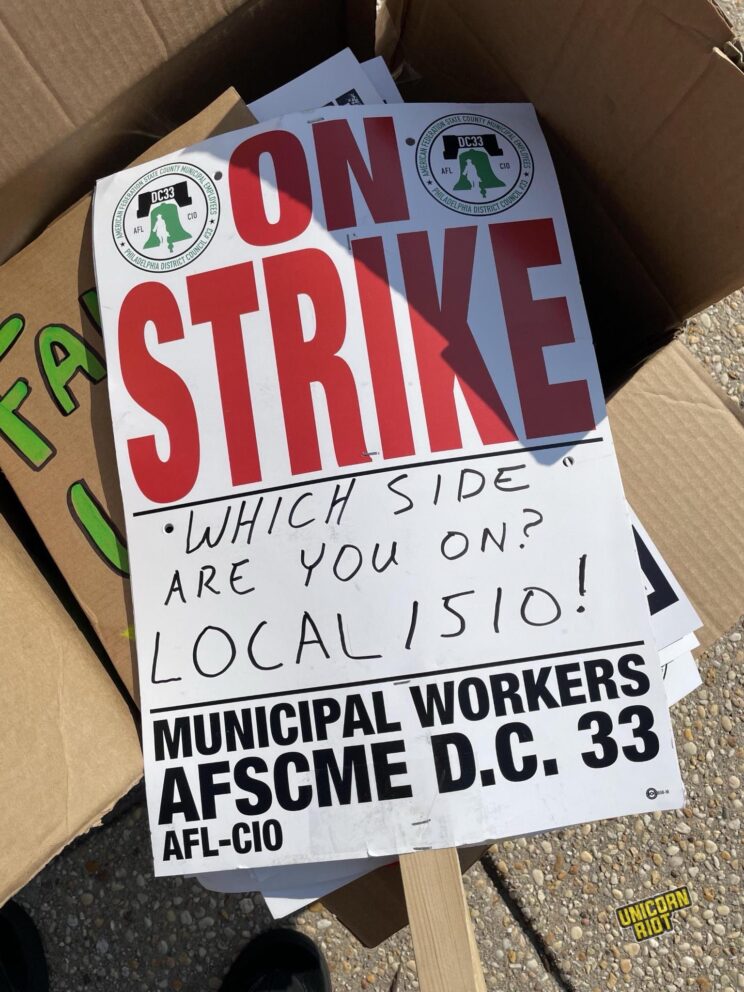

UR: There’s a lot of militancy in the origin story of the AFSCME chapter in Philadelphia starting with 222 and then eventually, after the huge garbage riots in 1938, DC 33 later became formalized. Do you see any parallels between past and present Philly garbage strikes?

DC 33 Worker: It’s complex. I wish it was a little bit simpler. I also wish that [union leadership] would’ve communicated to us that it was hitting the fan [in negotiations with the city] the night before it did.

There are plenty of escalations that members would’ve been willing to take on as it was hitting the fan, had they communicated that to us in any way. Not that we wanted them to come out and say “hey, it’s going really badly” and demoralize everybody. But there’s a way to say, “hey, here’s how it’s going in there, let’s ramp up a little.”

DC 33 Worker: This is my last thought about all this: when we had our strike captains meeting a couple weeks before the strike, they brought in a guy and they said this guy was working for DC 33 last time that we struck, in ’86, and he’s been holding out on retiring because he knows we’re due for a strike again.

He was so cool to hear from. It really did ground the whole room in what we were about to do. And if in the next 10 years they wanna strike again, they now have thousands and thousands of people who can play the role that that man played. The fact that people know what it’s like and know how to do it and know what brand of megaphone they wanna have and how to set up a tent in two minutes flat, that’s the kind of stuff that you only learn by doing it. That’s why I hope that this doesn’t cause a pendulum to swing where they’re much less likely to strike for another 50 years, because it’s so rare to have a union that has this many people with eight days’ strike experience.

He said something along the lines of, “I didn’t retire until this moment because I wanted to strike again” and that he had a positive experience of it. This meant we were all going into it not feeling like, “aw man, now we have to strike…” but rather, “hey, now is this moment that you get to exert power that you hold every day, but you very rarely get to make visible.” It amped people up that he had struck and had a positive attitude towards the idea of doing it again. I feel excited that there are now thousands of people who have that same experience.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: