St. Paul Teachers Union Strikes, Demanding Increased Mental Health Support for Students

St. Paul, MN – If a school district isn’t actively addressing the significant barriers preventing students’ education, is it reasonable to expect teachers to be successful at their jobs?

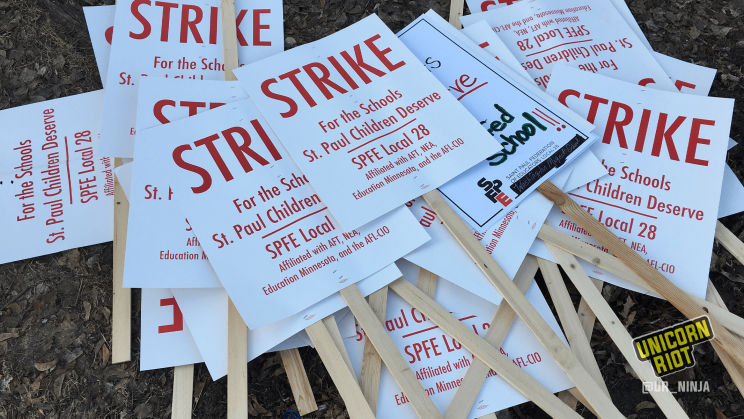

Providing resources to minimize barriers against youth learners is the focus of the 2020 labor strike by the Saint Paul Federation of Educators Local 28 (SPFE), which began on Tuesday, March 10. Teachers have been saying they don’t have the resources they need to do their jobs to the best of their abilities. After negotiating with Saint Paul Public Schools (SPPS) since May 2019, the teachers’ union authorized the strike on February 20.

Alec Timmerman, a math teacher at Washington Technology Magnet School, told Unicorn Riot that educators are striking “to tear down barriers that are in the way of our students’ learning.” Teachers want to focus on teaching, and the support students need falls outside of educators’ role.

According to an October 2019 report, A Statewide Crisis: Minnesota’s Education Achievement Gaps, Minnesota has one of the USA’s largest disparities in student performance by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. The ‘achievement gap’ between white and non-white students, also known as the ‘opportunity gap’, has persisted for decades as inequities have rooted themselves deep within the educational system.

“We give lip service in our society of wanting to close these gaps, but if we’re really gonna close these gaps, asking nicely hasn’t worked, and we’ve tried, so now we’re doing what we have to do.” — Alec Timmerman, SPFE Local 28 member

Timmerman emphasized that SPFE teachers’ main demand is increased mental health support for SPPS students, “especially in populations like ours where there may be low socioeconomic status or there may be marginalized populations. They face tremendous trauma in their day-to-day lives.”

Other demands include increased multilingual staff, additional educators to work with students with disabilities, and expanding restorative justice practices across the district. Picket signs read ‘Strike For the Schools St. Paul Children Deserve.’

The day the strike began, SPPS sent layoff notices to its Teaching Assistants, warning them that “should the strike continue, your last day of employment will be March 23, 2020.” The school district only receives money to pay its staff if classes are ongoing, and if classes are stopped, the district must choose to either operate with a budget deficit or fire workers. Teaching Assistants are represented by Teamsters Local 320, which expressed solidarity with SPFE Local 28 and is contributing $1,000 to the strike fund.

The educators’ union strike in St. Paul is the second in the history of the school district. The first was in 1946, a time when many Minnesota public schools had no soap or toilet paper, and students had to buy their own textbooks. ‘Strike For Better Schools‘ was the slogan of that first strike.

Led by Lettisha Henderson, Mary McGough and Manila Topdahl, the historic 1946 teachers’ labor strike was one of the first in the nation. Five weeks of striking ended in victory, raising the state spending per pupil and easing the path for collective bargaining for teachers all across the nation.

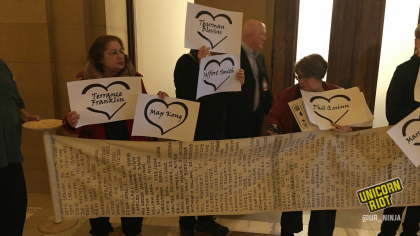

A key issue in the 2020 SPFE strike is one union members threatened to strike over in 2018 — a district-wide commitment to restorative justice programs in all schools. The SPPS Restorative Practices approach asserts that relationships are the most important way people learn about themselves and the world.

After union contract negotiations of 2015–16, teacher-student-parent discussion circles and other restorative practices began as a means for SPFE to address discipline issues in schools. According to the district, since then, they’ve “become a model for a healthy, racially equitable school culture.”

A September 2019 SPFE proposal regarding restorative practices states that “staff and students must experience emotional and physical safety in our schools.” The basis of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, taught in every psychology class, is that a person’s long-term goals cannot be prioritized until more immediate human needs have been met.

Physiological needs are at the foundation of Maslow’s hierarchy; food insecurity, lack of access to unpolluted air and drinking water, and homelessness are barriers to getting these needs met. Safety needs, next-highest on the list, can go unmet due to institutional racism, bullying, childhood abuse, or feeling as though their educator does not like or accept them. The next highest is the need for love and belonging — if a student feels like they don’t belong in their surroundings, they’re alienated from their environment and from their peers.

Paulo Freire’s foundational text The Pedagogy of the Oppressed taps Freire’s own childhood experience of growing up hungry during the worldwide economic crisis known as the Great Depression. He recalled feeling listless and falling behind in school while battling hunger pangs.

While Freire was writing in 1969 in political exile, the Black Panthers in the United States were already feeding poor Black schoolchildren, who were having difficulty learning in school due to hunger and poverty. The Panthers’ Free Breakfast Program became very popular with the public, and national attention was focused on the need to ensure all students have access to nutritious meals.

By 1975, as a direct result of the Panthers’ grassroots efforts, Congress had dramatically expanded the National School Breakfast and Lunch Programs, ensuring that hunger wouldn’t pose a barrier to the education of poor children nationwide. During the ongoing strike, students are still be able to get breakfast and lunch at 24 SPPS community meal sites.

Once students’ sustenance and shelter needs are satisfied, higher-order needs such as safety and belonging need to be met. District-wide restorative justice practices pushed for by SPFE Local 28 aim to make parents and students feel safe and welcome at school.

“Just like we feed ’em breakfast in the morning, we want to feed their minds and feed their souls so that they’re clear as well, so they can get about the business of learning.” — Alec Timmerman, SPPS educator

St. Paul educators’ related demands of more multi-lingual staff sourced from the local community, as well as staff trained with the skills to serve students with disabilities, would further reduce the barriers to Minnesota students’ education. Increased staff support would augment St. Paul teachers’ ability to help their students along their path to education.

Timmerman emphasized that none of the union workers wanted to be on strike, saying, “no one else is doing what they have to do to tear these barriers down.” Local 28 was moved to take direct action as a last resort to address the needs of their students and to begin closing Minnesota’s decades-old opportunity gap.

Niko Georgiades contributed to this report for Unicorn Riot.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: