Cambodian Union Leader Chhim Sithar to Remain in Prison After Court Rejects Appeal

Phnom Penh, Cambodia — The ninth of November was a momentous occasion for millions of people in Cambodia as they celebrated their nation’s independence from France which occurred 70 years ago. Government officials wearing uniforms of brilliant, spotless white paid their respects to the late King Sihanouk, the father of modern Cambodia, at Independence Monument and at the King’s towering statue. Crowds gathered in celebration at the gates of the Royal Palace, many to catch a glimpse of King Sihamoni, and the new Prime Minister Hun Manet.

But not everyone in Cambodia shared the same feelings of euphoria and jubilance on display by the throngs of people surrounding the Royal Palace. Just a short walk away, union activists and former employees at Cambodia’s largest casino, NagaWorld, hit the streets of Phnom Penh again to protest the recent Court of Appeals decision to uphold the convictions of union leaders.

The Labor Rights Supported Union of Khmer Employees at NagaWorld (LRSU) has been embroiled in a bitter labor dispute with the company since April 2021 when 1,300 union members were fired, a move seen by LRSU as a major effort to bust their powerful organization.

The Battle at NagaWorld: The Longest Strike in Cambodian History PT. I

The Battle at NagaWorld: The Longest Strike in Cambodian PT. II

Court Sentences Cambodian Union Leaders to Prison Amid Wave of Repression

The strike was baptized in fire by the authorities. Just two weeks after the strike started 8 union leaders, including LRSU president Chhim Sithar, were arrested and charged with incitement.

On the picket line, striking workers were routinely detained en masse, and violently attacked by the authorities.

The government’s crackdown on the union coincided with a rapid deterioration of human rights in Cambodia. Attacks on independent media, environmental and human rights activists, land defenders, dissidents, and the political opposition intensified leading up to the national elections which took place on July 23, 2023.

After what was widely viewed as a rigged election, the authoritarian leader of 37 years, Prime Minister Hun Sen, established a new dynasty in Cambodia when he passed the baton of power to his son and head of the armed forces Hun Manet.

In this climate of repression, the original strike of thousands of former and current employees has since dwindled down to small yet determined intermittent protests at the casino. While most workers have moved on to find jobs elsewhere, the remaining protestors are still fighting for reinstatement, and are demanding that the convictions of the 12 union leaders and activists be commuted, and charges dropped for other union members.

‘We want justice from the court’

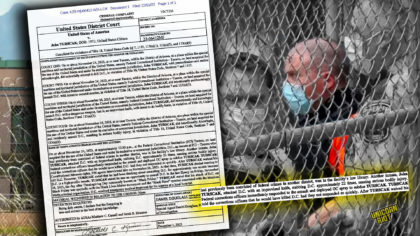

On October 27, a green van pulled into the entrance of the Court of Appeals. In the back seat sat LRSU president Chhim Sithar wearing a red jumpsuit. Chhim waved, and smiled at the cheering union members who had gathered outside. She looked calm and confident, even amidst the whirlwind of chaos that so often swirls around her and her union.

Ouk Sopheakmolika was one of many union activists who showed up to support Chhim. She stood in the shade across the street from the courthouse to protect herself from the sweltering Cambodian heat. “We want justice from the court and from the company, and we want the government to stop putting pressure on us,” said Ouk.

Activists waited for hours with a mix of stoicism and anxiety, a set of emotions forged by years of weathering the storm of labor protest and government repression.

In a prison system awash with political prisoners, Chhim Sithar’s case is one of the more high profile ones.

She spent 74 days in prison on an incitement charge after her first arrest in December 2021. She and other union leaders were released on bail, but she was again arrested at Phnom Penh International Airport after she returned from a trip to a labor conference in Australia on November 26, 2022.

Authorities claimed she violated conditions of her bail which barred her from international travel. Chhim’s attorneys, however, stated that the judge from her case never mentioned this, and that no court documents, and no communications were ever sent to Chhim or her attorneys.

The court finally released its decision to uphold the convictions against Chhim and the other union leaders. Ouk stated, “We regret the decision of the Court of Appeals. It shows us that this decision was not based on the spirit of the law.”

Appalling Prison Conditions

Also present outside the court was Chhim Sithar’s brother, Chhim Pov. When asked about his sister’s conditions in prison, he kept positive in an otherwise difficult situation. “She is doing fine but you know prison isn’t like our own home. Her health is okay but her mental health…. However, a lot of prisoners like her. And most of her time she reads books and crochets and makes flowers to send outside.”

Life in prison has not been easy for Chhim Sithar. During her initial incarceration, the Cambodian government kept Chhim Sithar and the other imprisoned union leaders in isolation from the outside world. They were denied access to news about the strike, were barred from talking to the media, and were denied access to attorneys.

The Cambodia human rights organization, LICADHO, stated in a report that “prisoners in Cambodia live in appalling conditions.” The organization describes the prison system as deeply corrupt. Inmates are used for forced labor, and torture and abuse is rampant. There are hundreds of political prisoners, a number that drastically climbed in the last year as the Cambodian government increased its repression leading up to the national elections.

Chhim Sithar’s activism and incarceration have served as an eye opening series of events for her brother. “I learned a lot from her. She made me realize the importance of unions. In the beginning I didn’t support her. But when she explained to me case by case how this is really an injustice from the company that can impact them without any reason,” he said. “After that, my family supported her.”

Chhim Pov is cautious yet still hopeful. One year is left in Chhim Sithar’s sentence and his sister has one last chance at an appeal with the Supreme Court. With a new prime minister, Hun Manet, at the helm, and despite the recent legal setback, Chhim Pov said, “I hope for Cambodia’s new prime minister to improve democracy and improve freedom of expression.”

He was quick to add, however, that, “freedom of expression is still narrow. As you can see, when you want to do anything you can’t express your own views.” His sister is one of hundreds of political dissidents and activists currently sitting behind bars because they took the risk of expressing their political views and acting on them.

‘No more rights under this corrupt system’

Despite the risks of encountering further repression, LRSU members continue to protest.

Union members added flare to an earlier protest held on November 5 when they performed a fashion show on the picket line. They donned flamboyant hats, and wore flowing gowns made out of trash and plastic. They wanted to send the message to management to stop treating them like trash.

“Now we still don’t have any solution so that’s why we did this protest,” said LRSU activist Mam Sovathin. “We try, we show up, and we let the people embrace it. We want to try to teach everyone how to protest to get their rights,” she said.

Mam is a regular at the protests, and is often seen leading demonstrators in chants. She was targeted in the initial mass firings at NagaWorld and has struggled to make ends meet as a single mother. She makes and sells paper flower arrangements to buy food and support her daughter.

Mam has lived under an intense form of surveillance — on numerous occasions she documented plainclothes authorities following her to her home or the market. Fearing for her daughter’s safety, she sent her to live with family in Phnom Penh’s outskirts, far away from any potential violence she may face from the authorities.

An exasperated Mam stated, “We still continue the strike but nobody cares. The minister of labor, and the prime minister of Cambodia still keep silent and then nothing happens.” Any direct government intervention into this is unlikely at this point, especially since the protests are smaller and more sporadic, and NagaWorld CEO Chen Kip Leong has a close relationship with the Cambodian government.

While there has been much talk of the potential change that might come from the younger generation of leaders who have recently stepped up to rule Cambodia, union activists fear that little will change under the new prime minister. A continuation of business as usual was made terrifyingly clear after the attempted assassination of government critic Ny Nak in September, the threat to close down Camboja, the last bastion of independent media in the country, and the sentencing of opposition party members to eight years in prison.

The human rights situation is so dire that it prompted the United Nations to send Special Rapporteur Vitit Muntarbhorn to Cambodia for two weeks in July to investigate the country’s descent into deeper repression. The UN published their findings, which included a lengthy list of recommendations for the government to rectify the situation.

The report adds weight to the assertion that Cambodia has the 30th most corrupt government in the world, according to Transparency International, an organization that tracks global corruption.

Despite this, Mam Sovathin is still holding onto a shred of hope that Chhim Sithar’s last appeal to the Supreme Court leads to some semblance of justice, but sees her country’s legal and political system as saddled with corruption. “I am also facing charges,” said Mam. “NagaWorld said I broke something but that’s not correct. We workers did nothing. It’s not true. We don’t do anything like that. We just protest to pressure NagaWorld to respect the law.”

As the country plunges ever deeper into a pit of repression and corruption, union activists have concerns that transcend to workers outside of their struggle at NagaWorld. “I think the government should care about this,” said Mam. “They must give justice to Khmer workers and not keep silent. And if there is still corruption, then I think workers in this country will have no more rights.”

Editors’ note: On Khmer (Cambodian) names. Names are normally written in the Khmer language with the surname first, and the given/first name last. This form was used in this article.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.