‘Makeba’ – A Viral TikTok Trend Pays Homage to Mama Africa

Whether you use TikTok or Instagram Reels, if you’ve been doom scrolling the last eight weeks, chances are you’ve heard the catchy “Can I get a ooh wee?” chorus of the song “Makeba,” a pop dance release by the French singer Jain. The meme, which started on TikTok, first gained virality as a simple dance and lip-syncing soundtrack. But within a few weeks, it gained even more recognition when a clip of a Saturday Night Live sketch featuring a dancing Bill Hader was added to Tiktoks with the song. Serendipitously, Hader’s corny dancing in the SNL clip synced perfectly with the BPMs of “Makeba.”

@tracymarietattoo Yup! #billhader #billhaderdancing #billhadersnl #mentalhealthtok #mentalhealth #tattootherapy #mentalhealthawareness #tattootherapyisthebest ♬ Makeba – Jain

The song has seen a noticeable uptick in streams which is remarkable given the song was released in 2015. The music video for “Makeba” was even nominated for a Grammy in 2016. However, for as big as the song has become on social media, its meaning has much deeper roots.

“Makeba” is a reference to Miriam Makeba, a South African musician who was lovingly known as Mama Africa across her home continent. More than just a figurehead in the pan-African diaspora, her music and political acumen were relatable to people of various backgrounds, especially Black Americans. Much like the issues Makeba had with South Africa’s apartheid, Black Americans had their own battles against segregation. “There wasn’t much difference in America; it was a country that had abolished slavery but there was apartheid in its own way.”

Makeba’s life continues to have a cultural impact, but it started out relatively humble and easygoing. Born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1932, Zenzile Miriam Makeba started singing at her church when she was quite young. But it wasn’t until King George and his wife and daughters, namely Queen and princess Elizabeth, came to visit South Africa in 1947 that Makeba was given her first solo to perform for the Royal visit. Even as a teenager, everyone noticed how talented she was and by the time she was a young adult in the 1950s, Makeba was performing professionally.

As Makeba began singing with a local group called the Manhattan Brothers, the white-minority South African government introduced even more laws to their already segregated system in 1952. Although she didn’t agree with the oppressive laws, the singer continued pursuing music. The following year, Makeba and the Manhattan Brothers had their first hit called “Lakutshon Ilanga,” raising her notoriety.

Towards the late 50s, Makeba joined the all-women group known as the Skylarks, singing a mix of jazz and traditional African songs. But as racial tensions in her country began to mount, she could no longer remain silent. In 1959, Miriam agreed to have a short cameo in an anti-apartheid film called “Come Back, Africa.”

Later that same year, she accepted the female lead in Todd Matshikiza’s all-African jazz opera “King Kong.” The opera was a landmark event given it took place in apartheid-torn South Africa and featured both Black and white performers, which was a direct challenge to the recent additional apartheid laws. The role she played in the opera in addition to her documentary cameo catapulted her and her music to international recognition and she moved to the United States to expand her career.

But as her career in the U.S. was beginning to pick up steam, the turmoil in South Africa came to a fever pitch. In 1960, during protests against apartheid laws, 69 people were killed and 180 injured in what became known as the Sharpeville massacre.

Protesters killed by the police that day happened to include two members of Makeba’s family. Shortly after the massacre, she learned that her mother had also died, prompting her to make travel arrangements to go back to her home.

However, as she tried to depart America, she learned her South African passport had been canceled and she unfortunately wasn’t able to attend her mother’s funeral.

“I always wanted to leave home. I never knew they were going to stop me from coming back.” Makeba remembered. “Maybe, if I knew, I never would have left. It is kind of painful to be away from everything that you’ve ever known. Nobody will know the pain of exile until you are in exile.”

Because of her profile, Makeba was able to call attention to the cruelties of apartheid without having to say a word. But that didn’t last for long.

Whether she felt responsibility as someone who was able to leave the country while others couldn’t or guilt because she couldn’t get back home, Makeba became increasingly vocal in opposition to apartheid and South Africa’s white-minority government.

“People think I consciously decided to tell the world what was happening in South Africa,” Makeba told The Guardian in an interview. “No! I was singing about my life, and in South Africa, we always sang about what was happening to us – especially the things that hurt us.”

Facing devastating losses in family and ties to her homeland, Makeba became more devoted to her music than ever. After meeting Harry Belafonte in London, the crooner became her mentor and colleague. He even encouraged her efficacious move to New York City, where she became immediately popular after recording her first solo album in 1960. “He was a good teacher and looked after me,” Makeba said of Belafonte. “He said, ‘You have such great talent, you must try not to be a tornado – be like a submarine.”

But Makeba’s popularity wasn’t just from her talent as a singer. The content of her music became equally popular due to the fact she sang about the injustice of apartheid while blending traditional African music within a Western structure. This way, she was able to share her music with a more diverse audience.

Makeba’s lyrics — often in Swahili, Xhosa, and Sotho — were one of the first times Americans saw authentic African representation. Many consider her to be the reason the “World Music” category in the music industry exists.

“Makeba’s frequent appearances on US TV and collaborations with Belafonte offered many Americans their first encounter with an African and helped to challenge sensibilities shaped by Tarzan movies,” wrote the New York Times. “She constructed an image of an accessible but cosmopolitan entertainer who affirmed her people’s struggles by the dignity with which she represented their culture.”

Makeba became more politically vigilant as the 60s progressed. Her music reflected her stance on anti-apartheid and civil rights and highlighted her political involvement with the Black Power and Black Consciousness movements.

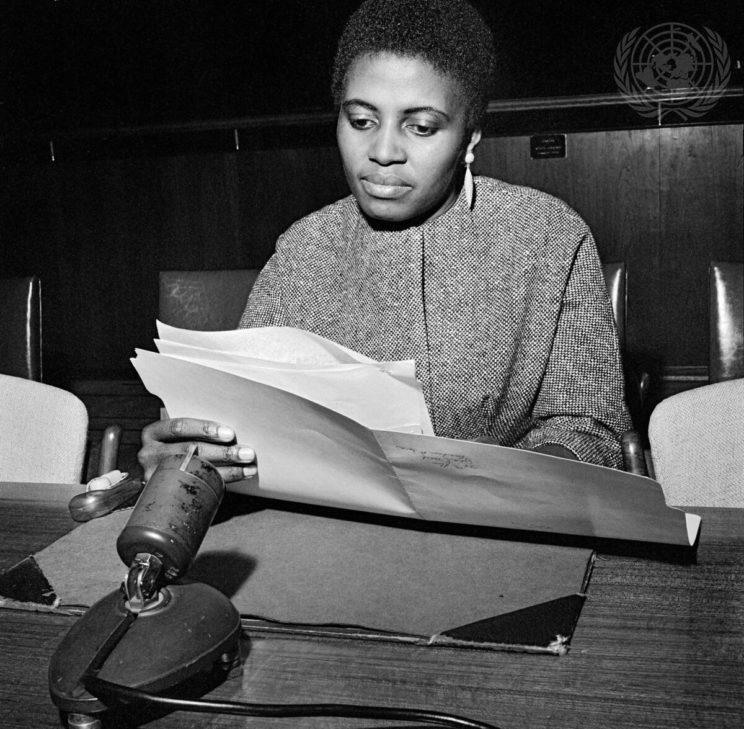

The tension between Makeba and the South African government came to an abrupt halt in 1962 after she testified in opposition to apartheid before the United Nations Special Committee against Apartheid. “I ask you and all the leaders of the world, would you act differently, would you keep silent and do nothing if you were in our place?” said Makeba to the UN.

“Would you not resist if you were allowed no rights in your own country because the color of your skin is different to that of the rulers, and if you were punished for even asking for equality? I appeal to you, and through you to all the countries of the world, to do everything you can to stop the coming tragedy. I appeal to you to save the lives of our leaders, to empty the prisons of all those who should never have been there.”

-Miriam Makeba addressing the United Nations Special Committee on the Policies of Apartheid of the Government of the Republic of South Africa, July 16, 1963.

After this public outcry against her government’s racist practices, South African authorities swiftly revoked her citizenship and her right to ever return back home. To add insult to injury, they banned her music in South Africa too. Fortunately, Makeba was given passports by Algeria, Ghana, Belgium, and Guinea. In fact, in her lifetime, Makeba held nine passports as well as citizenship to 10 countries.

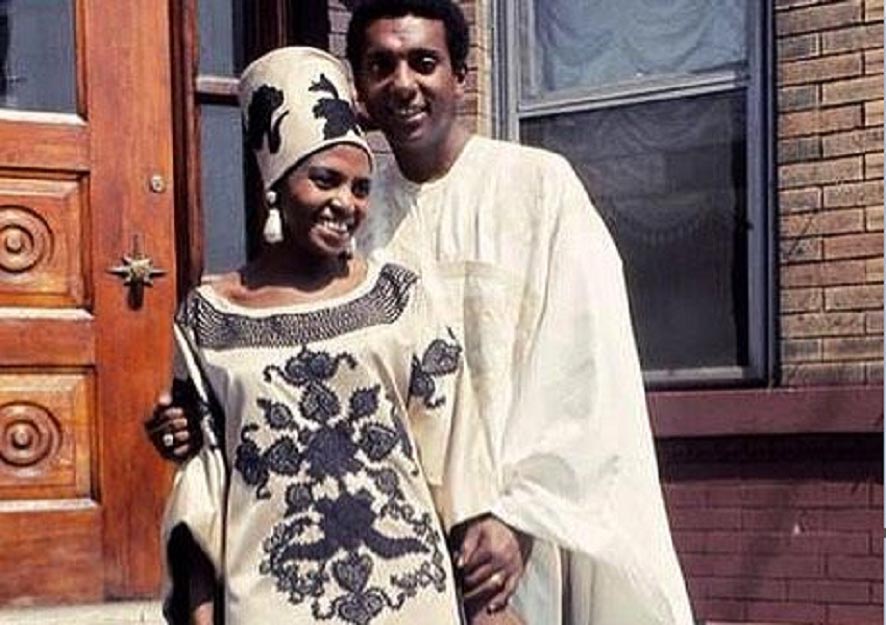

This wouldn’t be the first time her residency was revoked by a country either. After becoming more active in the United States’ Civil Rights movement, she married Kwame Ture (born Stokely Carmichael) in 1968 who just happened to be a prominent member of the Black Panther Party.

No longer winning over white Americans with her newfound status as a voice for Black power, Makeba found conservative media condemning her as an extremist while the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) set up recording devices in her apartment to keep monitoring both her and her husband’s activities. Deciding to go on vacation to the Bahamas, once Makeba and Ture made plans to return, they discovered the U.S. had canceled her visa and banned her from re-entry. She wasn’t allowed to go back to the states until 1987.

Relocating to Conakry, Guinea, where she lived for the next 15 years, Makeba continued releasing music and performing. Although she toured Europe and Asia, nothing compared to the welcome she received when she played in Africa. And as more countries gained their independence from oppressive European colonialists, she was invited to perform at their ceremonies, marking her as the voice for liberation.

“Africans who live everywhere should fight everywhere.” proclaimed Makeba. “The struggle is no different in South Africa, the streets of Chicago, Trinidad, or Canada. The Black people are the victims of capitalism, racism, and oppression, period.”

Makeba’s influence through pan-African countries could not be ignored — even by Makeba herself. At one concert in Liberia, while performing her most popular song “Pata Pata,” the crowd began making so much noise that she couldn’t even finish the performance. Despite the inconvenience, Makeba would go on record much later admitting that performance was when she finally started accepting the nickname of ‘Mama Africa.’ “I kept my culture. I kept the music of my roots,” said Makeba. “Through my music, I became this voice and image of Africa and the people without even realizing [it].”

In 1988, now a resident of Belgium, Makeba was invited to sing at the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute concert in London while he subsequently continued his prison sentence in South Africa. The show’s purpose was to raise awareness of apartheid and was influential in uncovering the growing global support for Mandela’s release from prison.

Two years later, after increasing international and local intimidation, the South African State President at the time, Frederik Willem de Klerk, reversed the ban on anti-apartheid organizations and released Mandela from prison.

Once he was released from prison on February 11, 1990, after serving 27 years, Mandela persuaded Makeba to return to South Africa given the end of apartheid had finally come to fruition. Later that year in June, Makeba finally returned home and would spend the rest of her life in residence there.

From 1990 until her passing in 2008, Miriam Makeba continued to sing all across the world, once saying, “There are three things I was born with in this world, and there are three things I will have until the day I die – hope, determination, and song.”

Her music and passion are undoubtedly some of the main reasons why people of the African diaspora think of her so fondly.

And Jain, whose mother is of Franco-Malagasy descent, lists Makeba as a musical influence, and in the verses of “Makeba,” you can clearly see the reference:

“I wanna see you sing, I wanna see you fight

‘Cause you are the real beauty of human rights…

Nobody can beat the Mama Africa

You follow the beat that she’s gonna give ya

Only her smile can all make it go

The sufferation of a thousand more.”

-Jain, “Makeba”

“She was South Africa’s first lady of song and so richly deserved the title of Mama Afrika,” said Mandela in a tribute to the icon after she died of a heart attack. “She was a mother to our struggle and to the young nation of ours.”

Controversially, many attribute the liberation of South Africa to Makeba, not Mandela. “People always credit Nelson Mandela for freeing us, no Miriam Makeba freed us,” said music executive Nota Baloyi in an interview.

“If it wasn’t for Miriam Makeba going to the US [and] meeting up with Harry Belafonte, she would not have gone to the UN. As far as Americans were concerned back then before Miriam Makeba spoke about [apartheid] to the UN, everything was normal.

She opened the door. Our freedom is due not to political leadership, it’s due to our musicians,” Baloyi continues. “It’s due to the artistic leadership of the ‘Mam Miriam Makebas.’ They are the ones who freed us.”

-Nota Baloyi

Cover photo via UNESCO/Wikimedia Commons: Miriam Makeba performs at the official launch event for The International Year against Apartheid at UNESCO’s Paris Headquarters on March 21, 1978.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: