Rave Against the Machine: How One Rave Promoter Stood Up to the DEA and Won

It Began with a Raid

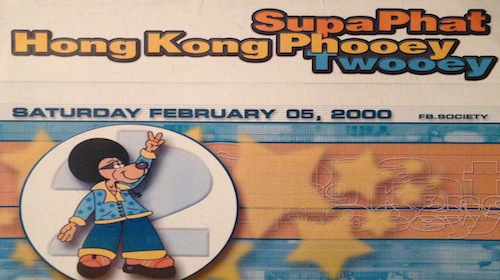

“Don’t come to the venue,” said one of the Brunet brothers to Disco Donnie on a clandestine phone call. Normally, Donnie, who is easily recognizable by his crazy outfits, would have already been at his party, he explained to me on a FaceTime chat one late April afternoon. But on the evening of August 26, 2000, he was still at home, likely perfecting his look for the event dubbed “Phuture Phat Hong Kong Phooey” located at the State Palace Theater in New Orleans.

Up until then, Donnie had been throwing wildly successful raves at the State Palace for many years. Erected in 1926, the Brunets took ownership of the theater in the early 1990s and made improvements to the historical site, some of which included returning the auditorium to a single screen and remodeling the adjoining commercial spaces so they connected to the theater’s main lobby, thus creating a large entertainment complex. Changing the name to State Palace was also part of the renovation.

“Phuture Phat Hong Kong Phooey” should have gone down as another successful party at the infamous venue but when Donnie answered the phone that night, it set forth a string of events altering the future of rave parties in the US.

“The place has been raided,” said the Brunets. “Don’t come here, they’re looking for you.”

“So, of course, I went there anyway,” laughs Donnie on our call. Living close to the venue, he arrived at the site to a scene of police cars, flashing lights, and confused patrons. Officers had sealed off the theater’s entrance leaving thousands of ravers spilling onto notorious Canal Street, scattering around the venue’s one-block perimeter. They had sold close to 4,000 tickets that evening, so the street had become the equivalent of rave carnage.

Attempting to avoid authorities but still piece together what was going on, Donnie avoided the theater entrance and walked towards the adjacent commercial spaces where he knew he could access the venue secretly. “There was some Middle Eastern restaurant underneath or something that was connected to the theater. It was all part of one big complex. So I went in the restaurant and I kind of made it my command post.” Gathering intel through back corridors, Donnie tried to reassure everyone, “I basically was just telling all the head promoters like, ‘Hey, just wait, the show’s gonna happen.’ Nobody knew what really was going on and at the time, neither did I.”

The Drug Enforcement Agency from the New Orleans field office had arrived at the State Palace Theatre at 9 p.m. to troll the premises, seizing files, opening the backs of the speakers and sound systems, taking computers, glowsticks and other party favors, and even confiscating as much bottled water as they could haul away.

Even though the DEA agents tore through the State Palace until 1 a.m., they found no illegal drugs inside the theater, besides the small joint that one bartender had on their person. They also found no proof that Donnie or the Brunets were involved in any type of drug dealing.

Free from the chaos happening upstairs, Donnie remained below deck, getting these updates while chilling in the restaurant. “I mean, I’m glad I didn’t have to sit through that,” he laughed.

Once the DEA left, the party resumed as planned.

Whack House Statute

It’s not like Donnie wasn’t used to police presence; in the past, his familiarity with local authorities was required to maintain the legitimacy of his shows and he worked with them if and when security found substances on entering partygoers. So when “Phuture Phat Hong Kong Phooey” was raided, he figured it had something to do with that.

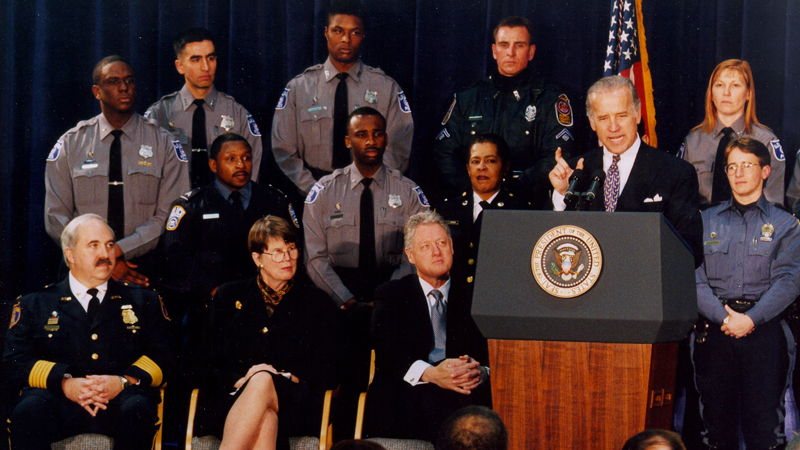

However, the following Monday morning after the show, Donnie learned that was hardly the issue at all. Joined with their attorneys, Disco Donnie and the Brunets realized they were being indicted under a grand jury for a violation of the “Crack House Statute” with an ongoing criminal enterprise. The crack house law, Title 21 U.S. Code, Section 856(a)(2) officially, was passed in the 1980s in an attempt to criminalize landlords and tenants who knowingly ran and operated crack houses. Then-Senator Joe Biden (D-DE) authored these federal crack house laws as a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Under these charges, the intention was to expand the definition of a crack house to include any businessman, club owner, or promoter on whose premises or at whose events illicit drugs are used or sold. And in the eyes of the DEA, Donnie’s raves, the Brunets, and the State Palace were the epitome of such. The penalty of the Crack House Statute included fines of up to $250,000 for property owners, promoters, and event managers and the defendants faced up to 20 years in federal prison.

The strange part about these charges though was that it was the very first time the federal government used the crack house law to indict venue owners and promoters for drug dealing and consumption at their events. Moreover, the DEA didn’t push for charges against the drug dealers or the ravers who consumed their products. Nor did their charges require proof that Donnie and the Brunets were actually selling the drugs.

But that’s not without trying. What Donnie wasn’t aware of was that the DEA had been surveilling his raves with undercover agents for the previous eight months. Calling it “Operation Rave Review” the DEA petitioned Congress for money to “assess the extent of rave activity in the New Orleans area” using Donnie’s State Palace parties as their test case. A document released by the Justice Department explains the eight-month “Operation” was meant to find a correlation between rave activity and club drug overdoses. In actuality, the undercover officers were collecting evidence to file for the search warrant needed to raid the theater later on.

Of course, it was easy for undercover agents to witness drug use at the State Palace; at one show on March 4, 2000, one agent made “a total of 25 purchases of controlled substances, particularly MDMA, averaging one every four minutes.” Other agents claimed, “neither the security guards nor the management of the State Palace Theatre did anything to curtail,” despite there being searches on arrival. The report said that the venue sold other “drug paraphernalia” at their events but mind you, these agents also proposed candy necklaces could actually be ecstasy and not just, well, candy.

“I should have known,” says Donnie. “It was on the Internet. They [DEA] were calling me on the phone, pretending they were promoters from out of town, asking me about throwing raves, trying to get me to say stuff about drugs. I’d tell them security keeps them out of there.”

The lack of understanding of the burgeoning rave scene coupled with growing negative media opinions, the DEA crafted a theory, “Basically, they were saying that I was the drug dealer, the owners knew I was, and together we were bringing the drugs into the venue to supply the shows.”

This explains why the sound equipment and lighting boxes were taken apart when the agents raided the venue. By their own admission, the DEA pointed to the sale of water as a sign of nefarious intent. They couldn’t fathom why thousands of people would pour in from adjoining states to dance to electronic music until the wee hours of the morning. At the time, it was really uncommon for fans to travel that far for just one night of music, and perhaps, in a misguided attempt to make sense of the growing popularity of the genre, the DEA thought the only reason people would do this was that they were making huge drug deals when they arrived. Never mind the possibility they just… liked the music and subculture.

“Their theory was that we would sell the drugs to the crowd from backstage,” Donnie continues. “They thought the drug dealers would have VIP passes and they would go out and sell the drugs and then bring back all the cash to me, the evil drug lord.”

After that pivotal Monday meeting with the DEA, Donnie learned that he faced a $250,000 fine and up to 20 years in federal prison. But Donnie was perplexed – he wasn’t selling drugs. He knew he didn’t do anything illegal.

To the Disco

In the early 1990s, you would’ve found a young James D. Estopinal waiting tables, trying to decide whether he really wanted to be an accountant or not. It didn’t take long for the Louisiana State University student to find his passion after co-workers started taking him to dance parties in New Orleans. “Electronica,” as people were calling it at the time, was enjoying a wave of interest as new subgenres began to develop from Chicago house and Detroit techno. Donnie fell in love with this dance phenomenon and decided to start throwing parties himself.

Disco Donnie’s first party, “Ultra Phat” was in 1994 and if it sounds like a laundry detergent to you, you’d be correct, “That was a big thing in the early 90s,” Donnie told me. “Using well-known brands [to advertise the party] and changing it up.”

Even though the location wasn’t ideal, Donnie remembers his first party fondly, “It was at a bar, but the bar had a kind of a warehouse vibe of upstairs.” Donnie continued using this warehouse throughout the year. “I mean, 500 people at like five bucks a head – it seemed pretty successful at the time.”

The warehouse fun came to a halt the following year in 1995 when police officers shut down the parties for unlawful booze sales and excessive noise. But Donnie felt confident he could build on the momentum he’d made at the makeshift location. In hopes of expanding his enterprise and making his parties more legit, he looked for other established venues in the city, eventually landing on the State Palace Theatre.

Waiting to Exhale

While the DEA outlined the full extent of his charges, Donnie grew more terrified for his future were he to go to trial. “When somebody’s telling you you could go to prison for 20 years, you don’t know who that jury could be, you know? They can put you in front of like… a bunch of grandmas!” he laughs on our call.

But the DEA was trying very hard to convince Donnie to take the plea deal they had concocted, “Basically, they were offering me a year.” he remembers. “Like they were just trying to get it done, right there. Like 20 years in prison versus a year.” As the agents continued to berate him, Donnie felt the walls closing in:

“People don’t understand – they hold all the cards. They sit you down and say, ‘We’re going to put 100 agents on this, they’re gonna come from DC, we’re going to arrest you at 6:00 a.m. on television and all the people that you went to school with, your mom, and family, and everybody, they’re gonna see you on TV, and we’re gonna bring you in here in handcuffs.’ They tell you, ‘We win 99.5% of these cases, you have no chance.’”

Disco Donnie

Donnie weighed his options, figuring that taking the plea deal would be better than taking a chance in front of a jury. But he knew there was a bigger issue facing the future of the music scene he loved so much. “To get that conviction would have stopped almost everything and not just for me, but for all music promoters. It would have put us all on a slippery slope if we set that precedent.”

Understanding the future of rave parties hung in the outcome of this case, Donnie decided to make a stand, knowing he didn’t do anything illegal. “I ended up going with a lawyer who had previously worked in the U.S. Attorney’s Office so he knew how the whole system worked.” With insider knowledge, his lawyer had a plan to string the DEA along in an effort to gather more intel about the evidence they had against his client. “[My lawyer] was like, ‘yeah, we’re just gonna go in there every week – we’re gonna tell them, ‘yeah, we’re gonna do the deal. Just lie and tell them we’re going to cooperate.’”

Donnie and his lawyer met with the DEA many times while they continued to build the case, all the while knowing that until he signed the plea deal that said he was guilty, Donnie was not guilty. His lawyer even asked him about the findings of Operation Rave Review, “He was like, ‘What have you done the last eight months?’ I said, ‘I don’t fucking know but I didn’t do anything illegal – I didn’t sell any drugs, that’s for sure.’”

So the plan to appear compliant continued. “They’re gonna keep giving us information and we’ll see if they really have anything on you.” Donnie recollects his lawyer’s strategy to me. Once the DEA started asking if Donnie would wear a wire, both he and his lawyer knew they didn’t have much, if anything, on him.

But because the DEA had put so much money into this test case, they had a painstaking desire to get some type of conviction, to their own detriment, some might say.

“They made the mistake by calling the press conference. And this was their fatal choice,” shares Donnie regarding the waiting period before going to Capitol Hill. This gave the case national attention even though the evidentiary support waned thin. “They went ahead and called a press conference thinking that they had this case all buttoned up. And the U.S. Attorney of New Orleans got on TV and said, ‘This is the most unconscionable drug offense he had ever seen in his 25-year career.’ This guy had prosecuted killer cops yet this was the worst thing he had ever seen in his whole career?”

Thinking the public would be on their side, after the DEA’s “dog and pony show,” as Donnie describes it, public opinion was the exact opposite. “Why are you arresting the promoter?” was the general consensus. In the newspaper, there were letters to the editor; on radio shows, callers gave their two cents; “There was a groundswell of support for us. I was pleasantly surprised… [everyone was] just talking about how much of an overreach this was. And that’s when the ACLU got involved.”

ACLU to the Rescue

Prior to the ACLU’s involvement, Donnie wasn’t sure if his representation was actually on his side, “Even my lawyer didn’t really know if I was telling the truth, you know? He was just manipulating the system. But when the ACLU got involved, I told them, ‘I didn’t do anything wrong.’ And they were like, ‘Yeah, you’re right.’”

Having the ACLU become his cheerleader gave Donnie more confidence to fight the charges. Releasing a press release in March 2001, just eight months after “Phuture Phat Hong Kong Phooey” was raided, the ACLU stood firmly by Donnie’s side. “Go after the people who deal the drugs,” said Graham Boyd, head of the ACLU’s Drug Policy Litigation Project. “But you can’t go after the people who provide the music–and you especially can’t go after only the ones who provide a certain kind.”

“Holding club owners and promoters of raves criminally liable for what some people may do at these events is no different from arresting the stadium owners and promoters of a Rolling Stones concert or a rap show because some concertgoers may be smoking or selling marijuana.”

Graham Boyd, head of the ACLU’s Drug Policy Litigation Project

It came down to this: everyone around the country, from law enforcement to prosecutors, were ready to jump on this “crack house” strategy if the DEA got the outcome they’d hoped for.

But on March 7, 2001, Disco Donnie and the Brunets, along with their lawyers and the ACLU, went to a hearing in federal court and entered their not-guilty pleas, and sought a dismissal of the case. Their lawyers also cited “a violation of their clients’ basic constitutional rights to free speech and due process,” stating Donnie and the Brunets “had been targeted because of the genre of music that they promote and the unsubstantiated association of that genre with rampant drug use.”

In a major victory for club and rave culture, the U.S. Attorney’s Office dropped all charges against the three defendants but fined the Brunet’s corporation, ‘Barbecue of New Orleans Inc.’ $100,000 for allowing the venue to be used as a site for the use and distribution of drugs. Subsequently, security at the State Palace increased.

The UnPLUR RAVE Act

Although Donnie and U.S. ravers rejoiced at the outcome of the case, federal legislators did not, among them being Joe Biden. Determined to make sure promoters and venues wouldn’t slip through the cracks of the crack house statute again, Biden introduced the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act of 2003 which would eventually become the Reducing Americans’ Vulnerability to Ecstasy Act of 2003 or RAVE Act.

The use of “rave” was deliberate for Biden but it was not PLUR, the raver mantra which stands for peace, love, unity, and respect.

Moving past the blatant unPLUR acronym, the RAVE Act prohibits an individual from knowingly opening, maintaining, managing, controlling, renting, leasing, making available for use, or profiting from any place for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance, and for other purposes. And with the extensive definition, the aftermath of this law is still felt today. Raves have colloquially been changed to mean club events and festivals but the days of 12+ hours of programming, legally, are few and far between.

Still in a sunset state of mind ☀️ thank you to all our amazing staff & crew for all your hard work + pulling off another successful @smftampa 🫶🏻 pic.twitter.com/odpUumZbEp

— DiscoDonniePresents (@DDPWorldwide) May 30, 2023

Now, as the owner of Disco Donnie Presents, one of the largest event organizers in the U.S., Donnie has found a way to keep the party rocking while appeasing all legal guidelines. And when I asked him to weigh in on President Joe Biden, he was very quick to let me know that he stays above the political fray.

Rob Brunet, however, was very vocal about a Biden presidency in an interview with Billboard, sharing, “Obviously, I’m not a fan.” He later points out that both the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Louisiana Eddie Jordan, who staged that press conference, and Thomas Porteuse, the judge who presided over the case, were later forced to step down from their positions over drug and discrimination scandals, “I thought that was a little comical.”

Cover image composition by Dan Feidt; background photo courtesy of Abandoned Southeast; Photo of Disco Donnie via Disco Donnie; DEA Patches via Curtis Waltman at MuckRock.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.