‘Don’t Forget Us’: Forest Defenders Confront Horrors of Life in DeKalb County Jail

Monica had been locked up in Dekalb County Jail for five days when guards entered her pod and called out her name. She was being released.

Like always, the other women in the pod started clapping and cheering, happy to see anyone freed. Monica got up and went to her cell to start gathering her things, interrupted as she did by hugs and goodbyes from friends she’d made during her time there.

As she walked toward the cellblock door, one of her podmates stopped her for a hug. As she let Monica go, she looked her in the eyes and delivered a clear request: “Don’t forget us here.”

“I won’t,” she promised.

“That was a moment I will never forget,” said Monica, weeks later.

Monica, a forest defender who asked to be identified by an alias, was arrested on January 18, 2023, during a multi-jurisdictional raid on the Weelaunee Forest in DeKalb County, Georgia. Protesters had been camping and gathering in the forest for months in hopes of preventing the construction of a multi-million dollar police training facility, dubbed ‘Cop City’ by its opponents.

On the day Monica was arrested, Georgia State Troopers shot and killed Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, a 26-year-old forest defender who went by the name Tortuguita. Subsequent autopsy reports revealed that Terán’s body suffered 57 bullet wounds. During the same raid, Monica and seven others were arrested, charged with “criminal trespass” and “domestic terrorism,” and booked into the DeKalb County Jail.

Monica was granted bond and released after five days, but most of the women she lived with in the jail had been there much longer, some for over a year, awaiting trial. Other forest defenders served a month or more in the jail, including two, Victor Puertas and Luke Harper, who were arrested at a music festival in the Weelaunee Forest on March 5 and remain in custody nearly 12 weeks later. Another forest defender is still currently incarcerated in the Bartow County Jail.

Unicorn Riot spoke with and received testimony from more than a dozen people who were formerly incarcerated at the DeKalb County Jail, as well as family members of those held there and others familiar with conditions in the jail. Most of those interviewed requested that their names be withheld out of concern that sharing their stories could affect their ongoing legal cases. Most of those interviewed were ‘Stop Cop City’ activists, while others were held on unrelated charges.

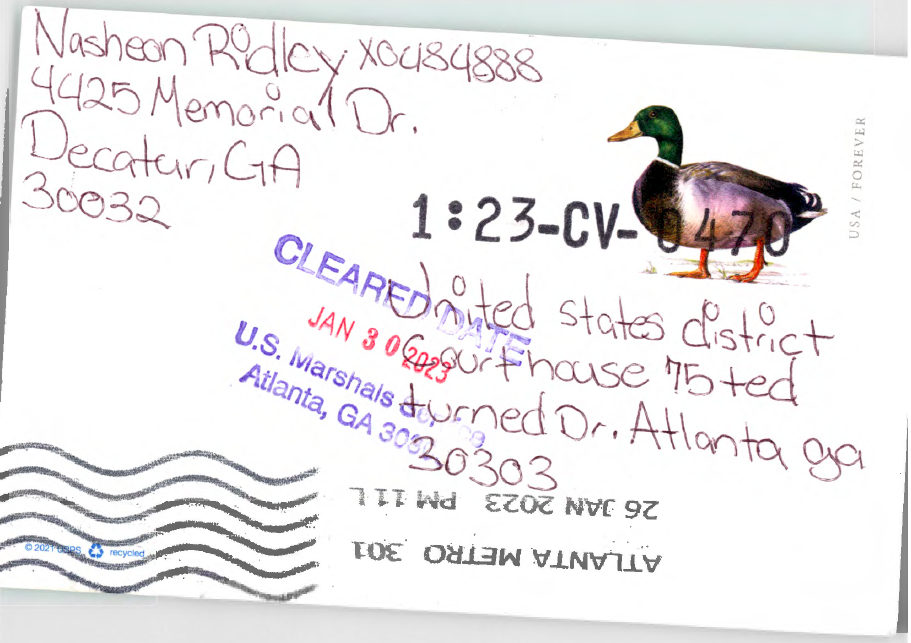

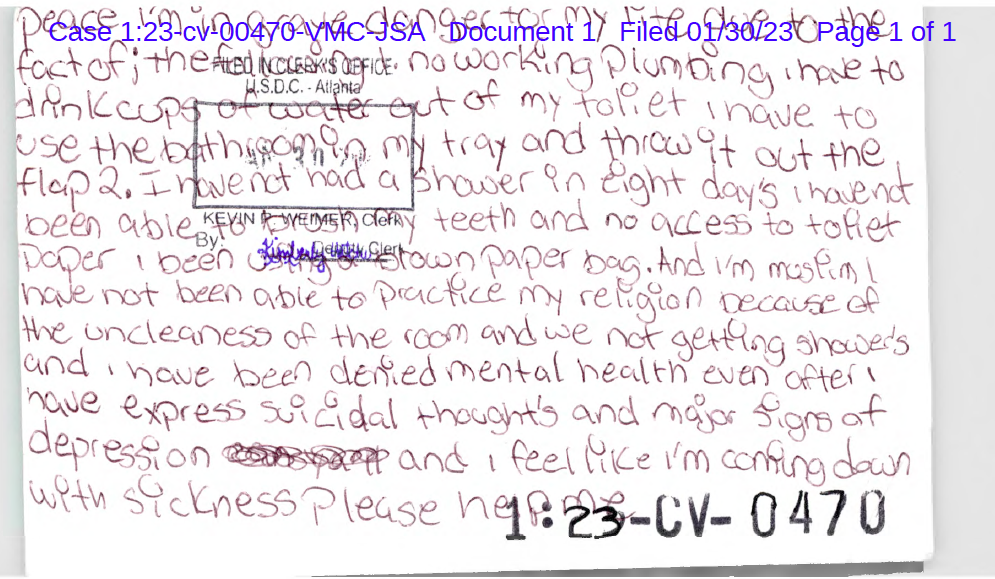

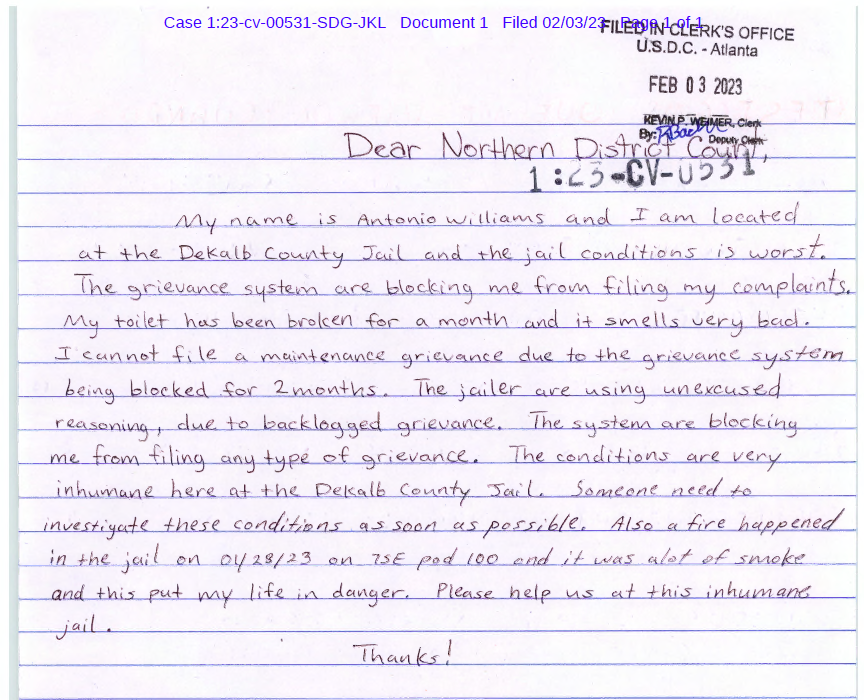

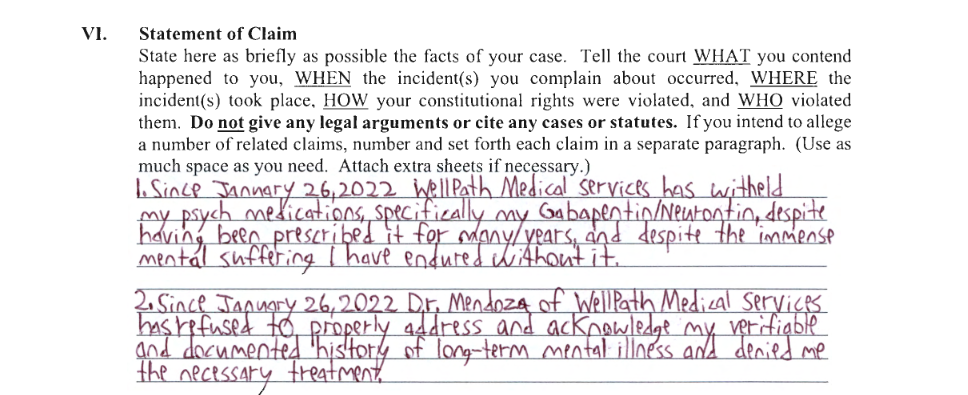

Unicorn Riot also reviewed dozens of pages of lawsuits filed by jail detainees raising civil rights complaints against the jail, the DeKalb County Sheriff, and its staff and contractors. Many of those lawsuits were filed pro se, without the help of an attorney, and handwritten on postcards purchased at the jail commissary. Many such lawsuits are dismissed on procedural grounds before lawyers for the Sheriff’s Office are even compelled to respond.

The stories they told each capture an existence, a moment of suffering, a tale of misfortune that would otherwise remain unseen. Taken together, they form a chronicle of inhumane, and often grotesque, conditions of confinement caused by a culture of neglect and apathy on the part of guards, contractors, and jail staff, often exacerbated by crumbling jail infrastructure.

In 2022, those conditions led to the deaths of nine people in the jail, a number that far exceeds the national average. Two of those deaths appear to be attributable to hypothermia after detainees were left in unheated cells in the winter. Others died by suicide or heart conditions after not receiving proper medical attention. Several of those who died in the jail had a history of struggles with mental illness.

“Nothing’s ever anybody’s job and it’s never nobody’s fault,” said Dulce, a woman who spent more than a year in the DeKalb County Jail who asked to be identified only by her nickname. “So it’s hard to get things done like they’re supposed to. Even with our food, they’d give it to us when they felt like it. We sat and watched our trays sitting in the hallway for hours. But because it wasn’t anybody’s job to do it, it wouldn’t get done. So we’re hungry just sitting there waiting for our food.”

Many of those we spoke with said they spent their time in the jail waking up at 3 or 4 a.m. to eat breakfast and then often going without food for 12 hours or longer. They talked about surviving on very few nutrients because they were often served undercooked or moldy food, much of it inedible. Some said they mopped their floors several times a day because the toilets or sewage pipes continuously seeped water and were never repaired, causing large puddles to form in their cells and pods.

“The area that I lived in, 24 gallons of water was leaking out of the toilet area per day: 24 gallons,” said one former detainee who was held in the jail for more than four months. “I know for a fact it was 24 gallons because I, and another inmate, we mopped up three buckets a day. Eight gallon buckets…24 gallons of water leaks out daily.”

Many lived in pods with few functioning toilets and lived with the smell of bodily waste they couldn’t flush. Others said they flushed their toilets and they’d keep flushing for six hours or more, sometimes flushing all night. “And jail toilets are very loud, in case you didn’t know.”

Some said they slept with the lights on in their cells because the guards simply refused to turn them off. They all said they rarely, if ever, got recreation time.

One person, who spent over two weeks in the jail, said the recreation area was available for about 5 or 6 hours during his entire stay. Still, he chose to stay inside because the recreation area was so “depressing.”

“It smelled like stale piss,” he said. “And you can see outside but…it’s just a bare room. People are just running back and forth or something. I’d rather just stay inside than get teased with outside but not even getting the fresh air because there’s a backed up toilet.”

Whitney Knox Lee, an attorney at the Southern Center for Human Rights, said that recreation time at the jail is so rare that “to date, most people in the jail haven’t been outside other than to go to court or doctors appointments in years.” The Southern Center for Human Rights is a nonprofit law office that is closely monitoring conditions at the jail.

A July 2022 email from the jail’s medical contractor, Wellpath, obtained by Unicorn Riot, recommends that recreation at the jail “not occur at this time due to increased number of [COVID-19] positive inmates.” The email, sent by Wellpath Director of Nursing Iesha Brown to the DeKalb County Jail, does not explain why giving jail detainees access to outdoor areas of the jail, presumably better ventilated than indoor spaces, would increase the spread of COVID-19.

Neither Wellpath nor Director Brown responded to requests for comment.

Most of those interviewed about jail conditions said detainees were consistently denied much-needed medications, such as insulin, blood pressure medication, antidepressants and antipsychotics. One said a woman who had been denied blood pressure medication passed out in her arms as the guards looked on, unconcerned.

Many said they witnessed patients experiencing severe mental illness locked in their cells 24 hours a day without access to psychiatric medications or treatment—and at times without access to food and water. Many said they lived with the screams of detainees suffering from untreated psychosis ringing in their ears.

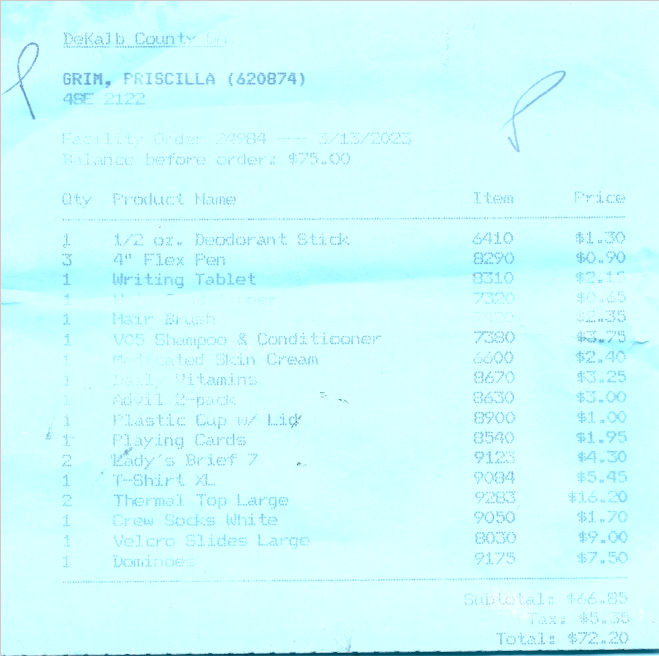

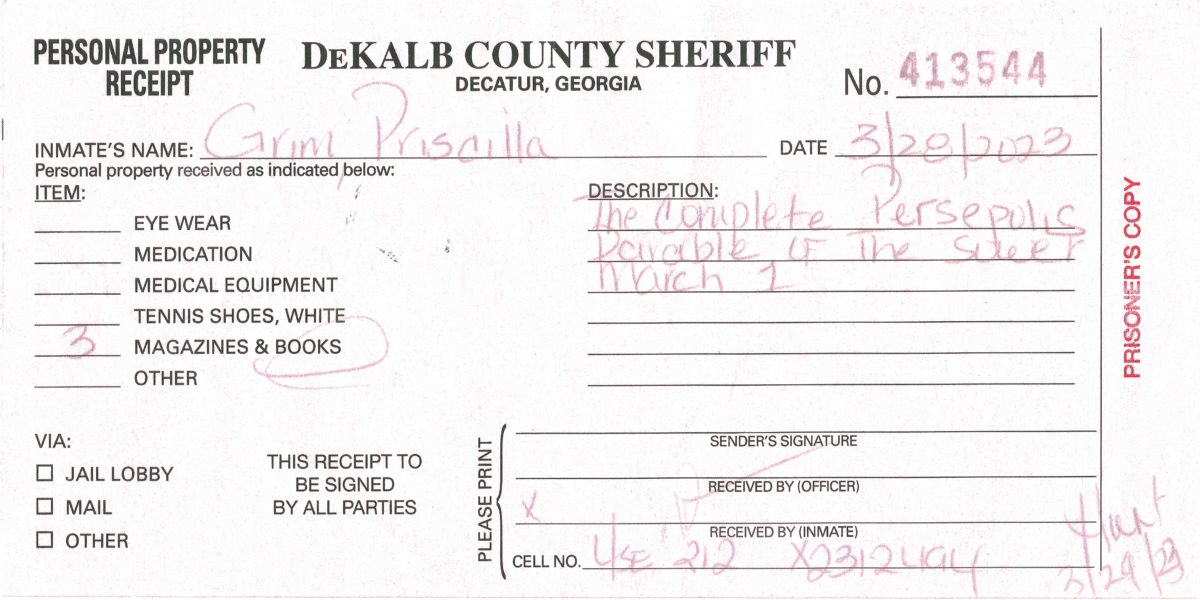

Priscilla Grim, a 49-year-old mother, activist, and writer, traveled from her home in Brooklyn to the March Week of Action against the ‘Cop City’ project. Grim was imprisoned in the DeKalb County Jail for 31 days and charged with domestic terrorism after she was arrested on March 5. Grim’s family is from DeKalb County, and she was born in Atlanta.

Grim and other forest defenders told Unicorn Riot that a woman experiencing mental illness in their pod was locked in her cell without access to drinking water for days. Grim watched as her friends filled plastic baggies from their lunch with water and pushed them under the door so the woman didn’t have to drink out of the toilet. Grim filed grievances demanding the woman receive care.

Another forest defender described a person obviously suffering from a mental health crisis who was locked in his cell 24 hours a day, frequently sitting in his own feces. He smeared feces on the walls of his cell and on his body. Guards, the forest defender said, would often forget to open the man’s cell door to give him food. Other detainees on the pod would keep an eye out to make sure he got fed or pass food under his cell door if he was hungry. “The whole pod looked out for him.”

“I think the thing that bothers me most is that nothing was taken seriously. Nothing,” said Dulce. Over the course of more than a year, Dulce said, she observed a near-total disregard for human suffering on the part of jail staff. Whether detainees were hungry, having untreated mental health episodes, or not getting life-saving medications, the guards never seemed to care. Even suicide attempts, Dulce said, were treated with indifference.

“I remember thinking I’d rather be homeless and free than to be in jail,” said Dulce.

Over the course of that year, Dulce said she saw three women try to hang themselves with bedsheets. One narrowly survived the attempt when Dulce and another woman pulled her limp body back over the railing on the upper tier of the pod. When they loosened the sheets around the woman’s neck, she started breathing again.

The most recent of those attempts occurred in March 2023, when ‘Stop Cop City’ activists were held in the same pod as Dulce. They described pressing the call button to get the guards to open the woman’s cell so they could untie her from the top bunk where she was hanging. When guards refused to respond, the women in the pod began banging on the glass together and screaming. Eventually guards opened her cell door and detainees rushed in and untied her. She survived, and the women in the pod stood against the wall and watched as guards led her away.

Three of the nine people who died in the DeKalb County Jail in 2022 died by suicide. All three hanged themselves.

The DeKalb County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to multiple requests for comment on jail conditions.

In the DeKalb County Jail, those working to defeat the ‘Stop Cop City’ movement have found one of their most potent weapons. After months of heavy repression, beginning with the first domestic terrorism charges in mid-December 2022, a pattern has begun to emerge: arrest protesters, often indiscriminately, charge them with scary sounding things like “domestic terrorism” based on very little evidence, and then use those charges as an excuse to hold them in jail without bond.

Since December 2022, 42 people have been charged under a rarely used Georgia domestic terrorism statute for their participation in the movement. At the time of this writing, 3 movement participants remain in jail.

“I think they know it’s so shitty [in the jail] and that they’re using it as a threat,” said one forest defender who was held in DeKalb County Jail for 2 ½ weeks in March. “It’s so obvious. It’s all just a thing to deter people from coming out and showing up because they know how bogus the [domestic terrorism] charge is, that it could happen to anyone for any reason, just for being in proximity to the movement.”

But the conditions at the DeKalb County Jail long predate both the Atlanta Police Foundation’s plan to construct ‘Cop City’ and the birth of the movement to stop it. Most of those incarcerated in the jail, including those held there the longest and in the most egregious conditions of confinement, are not forest defenders: they are the people of DeKalb County, especially those who are Black, who are poor, and who struggle with mental illness.

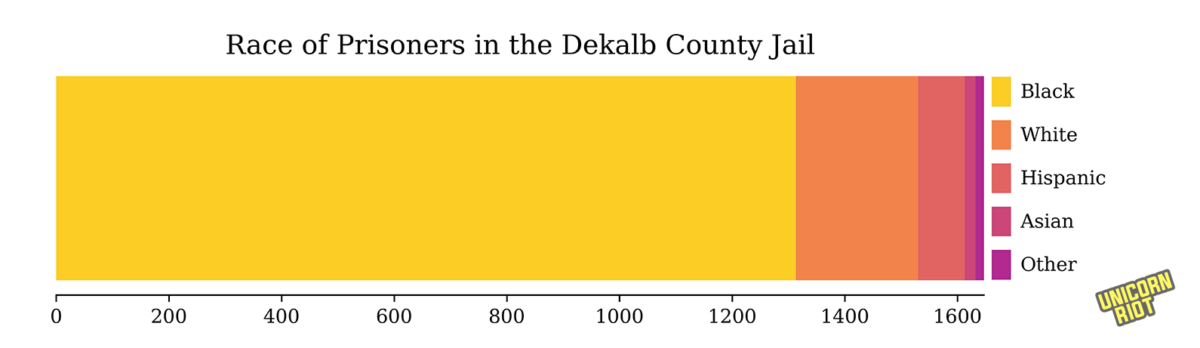

According to an analysis of booking records obtained by Unicorn Riot, as of March 23, 2023, the DeKalb County Jail held 1,647 people, nearly 80% of whom were classified by the jail as Black. Black residents make up just 54.6% of the population of DeKalb County, according to U.S. Census Bureau data from July 2022.

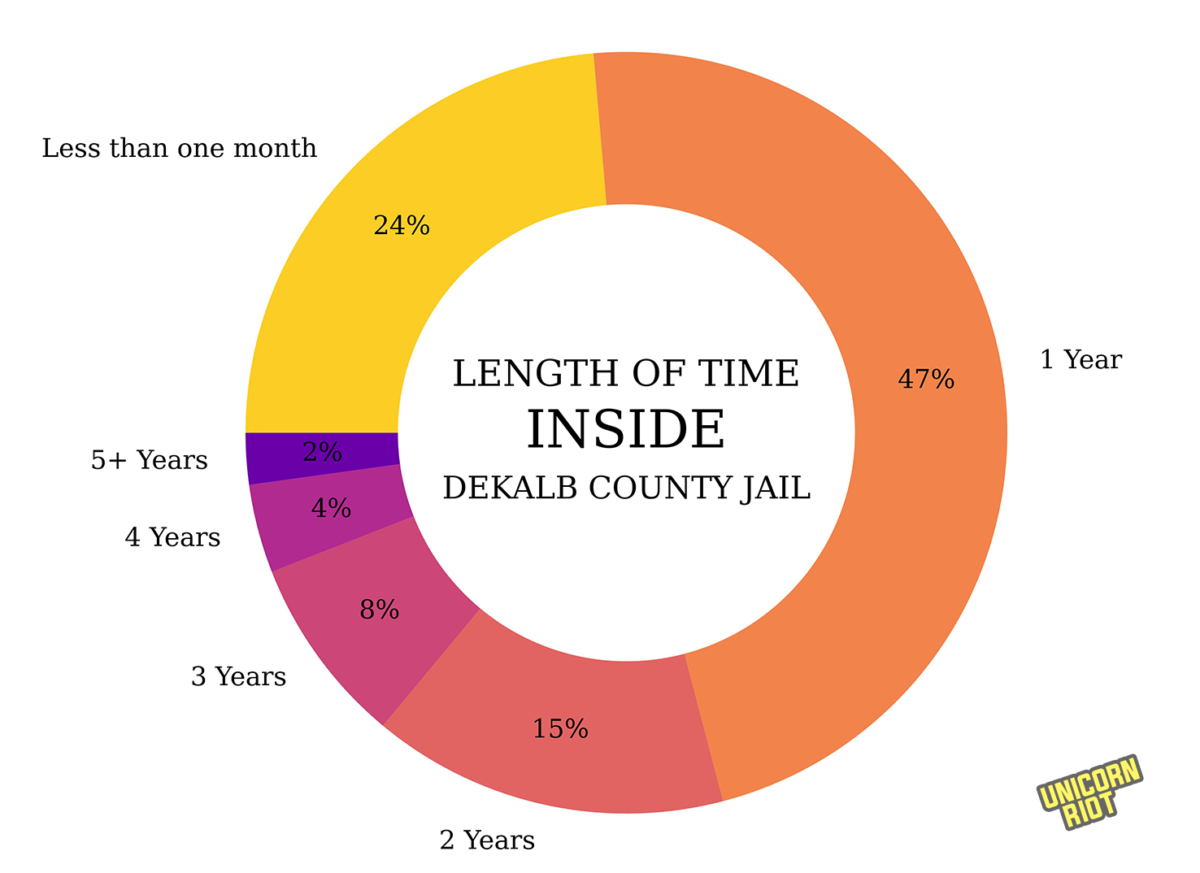

The majority of those booked into the jail remain there long enough to lose their job, fall behind on rent and car payments, or otherwise cause chaos in their lives. About 76% of those booked in the jail will remain there for more than a month, and about 29% will be held for more than a year, with some detainees living in the jail for three or four years, or more. One person has been held in the jail since 2016, according to jail records.

“…A whole bunch of nothing.”

Most days, what happens in DeKalb County Jail stays in DeKalb County Jail. Besides the information that trickles out through the prison phones and visitation rooms, it takes a story of spectacular violence or particularly egregious negligence to catch the attention of the news media. Average people, at best inured to the suffering of those in state custody and at worst desirous of it, seem only to react to the exceptional, the bizarre, and the grotesque.

What gets lost in this attention economy is the quotidian suffering of the millions of people in this country living behind bars: the weeks spent without access to recreation time, sunlight, or fresh air, the guards who, as one DeKalb County Jail detainee put it, seem to think being cruel to detainees is “the best part of the job.” The leaking sewage, the black mold, the hunger.

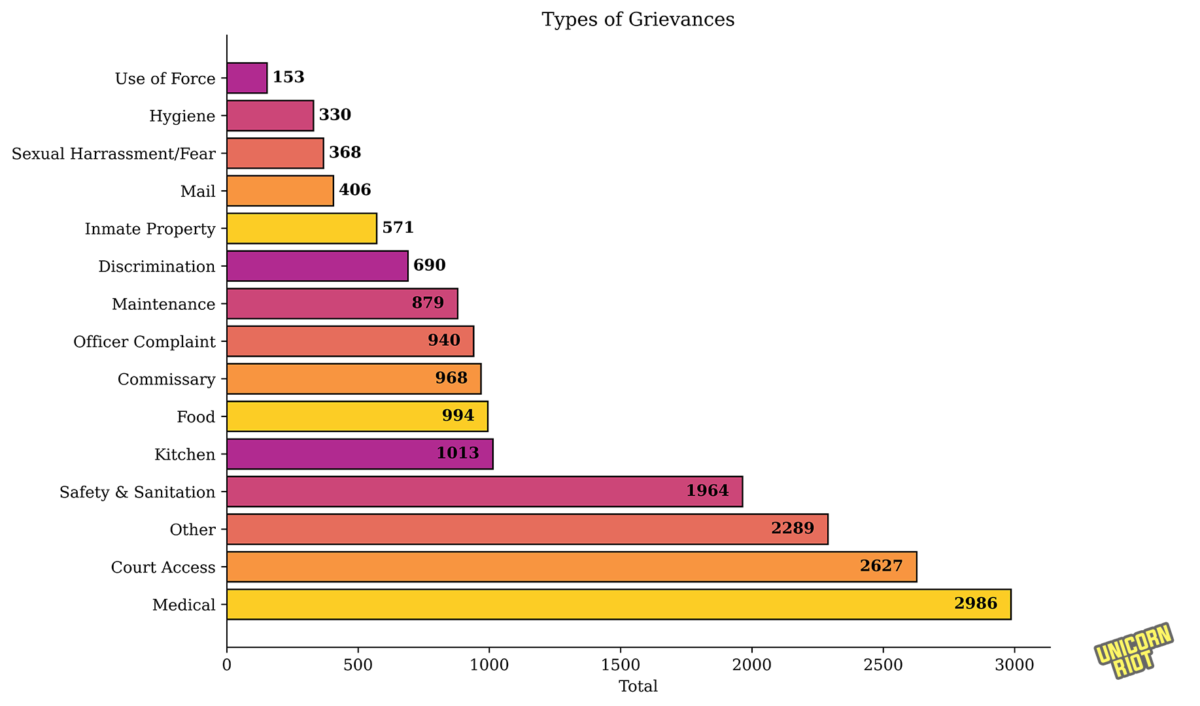

Those complaints, however, are chronicled by the detainees themselves and captured in the historical record whether anyone is listening or not. Day after day, detainees document their suffering via the jail-provided grievance system. On the wall-mounted kiosk or on tablets provided to detainees by the jail, they type out their sorrows, tell their stories of abuse and neglect, and beg for help. Those grievances, sometimes numbering as many as 2,000 per month, record human suffering in the form of drop-down menus, multiple choice grievance topics, and exportable fields for capturing date, time and inmate number.

Unicorn Riot analyzed metadata on more than 17,000 grievances filed by DeKalb County Jail detainees between January 1, 2022 and May 4, 2023. The data was obtained by a public records request. The DeKalb County Sheriff’s Department did not release the narrative content of those grievances, claiming that they could not export the content of the grievances en masse.

The data received by Unicorn Riot included information on the detainee who filed the grievance and other metadata including date, time, and pod, as well as the subject of the grievance. The data also contained information on the jail staff member assigned to manage the grievance and whether the grievance had been resolved.

The grievance software allows detainees to choose from one of at least 15 subjects, such as “safety and sanitation,” “medical,” and “use of force.” In 2022 and the beginning of 2023, detainees filed the most grievances about medical care, court access, and safety and sanitation.

Despite the large number of grievances filed, many detainees interviewed by Unicorn Riot said most people living in the jail don’t use the grievance system.

“Most people who came in just wanted to cry and be left alone,” said one female detainee. “All they were focused on was getting out.”

One forest defender said when he got to the jail, other detainees told him not to bother with the grievance system. “I just heard it was a whole bunch of nothing,” he said.

“They just said don’t bother. It isn’t worth it, nothing comes of it.”

All grievances filed by detainees are automatically assigned to a jail staff member. The staff member then determines whether the grievance was valid or not, eventually marking them “unfounded,” “founded,” or “sustained.” However, only 10 percent of the grievances filed in 2022 and early 2023, including the oldest ones, had been marked as “resolved” or “complete with objection.” The DeKalb County Sheriff’s Department did not respond to a request for information on the grievance resolution process.

Indeed, most of those interviewed by Unicorn Riot said the majority of their grievances were ignored by jail staff or given responses that seemed like a brush off.

Detainees filed grievances about medical attention more than any other subject area. Those interviewed by Unicorn Riot said medical treatment in the jail is highly unreliable and jail medical workers didn’t really seem to care about helping those held in jail custody.

Medical services at the jail are provided by Wellpath, one of the largest for-profit medical corporations in the U.S. Wellpath holds contracts with more than 350 local jails as well as more than 135 adult and juvenile prisons. DeKalb County has paid Wellpath more than $53 million since it began its contract with the company in February 2018 — an average of about $10.6 million per year.

Prisoners, detainees, and their families have repeatedly sued Wellpath for allegations of wrongful death and failure to provide adequate medical care. A lawsuit filed this month by the family of a man who died of hypothermia in the DeKalb County Jail in 2022 claims Wellpath did not provide adequate mental health and medical treatment to the detainee, Anthony Walker.

Mental health services at the jail are contracted with Centurion Health, which currently has an active job posting for a full-time psychiatrist for the DeKalb County Jail.

In December 2022, a detainee named Joshua Moubarak filed a civil rights claim against DeKalb County Jail Sheriff Melody Maddox and a jail doctor identified in the lawsuit as “Dr. Mendoza.” In the lawsuit, Moubarak alleged that Mendoza refused to provide him with Depakote to treat his bipolar disorder for 18 months, leading to suicidal thoughts, self-harm, and fights with other detainees.

A lawsuit filed by a Cobb County Jail detainee named Cannon Davidson against the Cobb County Sheriff and Wellpath makes similar allegations against Dr. Mendoza’s denial of needed psychiatric medications.

“We’re all comrades.”

Although some of those formerly incarcerated at the jail told stories of violence and predation on the part of detainees, most spoke of solidarity and acts of care that transcended the daily horrors of jail life. Most forest defenders said that they were humbled by acts of generosity and kindness and were able to use their time there to build relationships with people they may not have otherwise encountered.

Since getting out, several of those detained for their participation in the ‘Stop Cop City’ movement said they have remained in touch with those still locked inside and have sent books and raised money for their former podmates.

“The people I was in there with were the most stellar human beings on the planet,” said one forest defender. “95% of the women I was in the pod with were totally stellar individuals, literally caught up in a rotten fucking system.”

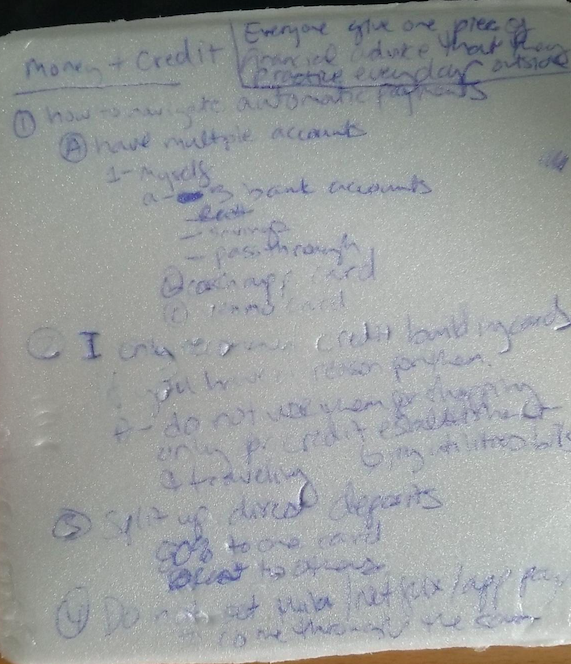

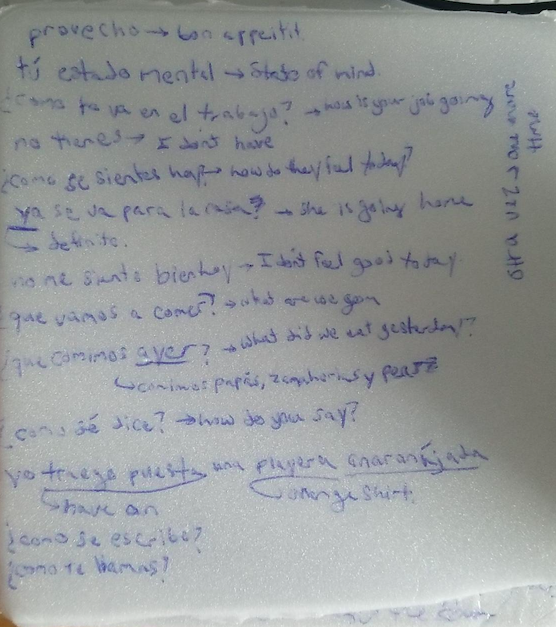

Grim and other detainees said a forest defender in their pod organized seminars, with detainees taking turns as the teacher. Topics included Spanish, cryptocurrency, basic emergency first responder skills, financial literacy, and pressure points for massage therapy.

Detainees also spoke of coming together to resolve conflicts between people held in the jail. Grim said she and other detainees at some point realized that someone was stealing commissary items from others in her pod. When they figured out who was doing it, they spoke to her and told her to ask people for help instead of stealing.

“We tried to talk to the people who were doing that,” said Grim. “We’re like, if you need something, just ask others, they will help you out. You don’t need to violate your comrades, which is what we are in here. We’re all comrades.”

Title Image: Nuyorican activist, writer, and digital strategist Priscilla Grim poses for a portrait in her home in Brooklyn on May 17, 2023. Grim was arrested during a gathering in the Weelaunee Forest outside Atlanta and spent 31 days in the DeKalb County Jail after Georgia prosecutors charged her under a rarely-used state-level Domestic Terrorism law. They have yet to present any individualized evidence linking her to the alleged acts. The paintings behind Grim were done by her grandmother at her home in DeKalb County, Georgia. Photo by Tracie Dawn Williams.

DeKalb County Jail Records Obtained by Unicorn Riot under the Georgia Open Records Act:

- 03.22.23_Current_Inmate_Report.csv

- Wellpath Director of Nursing Iesha Brown, BSN, RN July 16, 2022 email cancelling recreation (PDF)

- DeKalb County Jail Grievances January 2022 – May 2023 (.ZIP archive, 2.5 MB, 14 .xlsx spreadsheet files)

Unicorn Riot's coverage on the movement to defend the Atlanta Forest:

- Landing Page: Unicorn Riot Coverage of the Movement to Protect the Atlanta Forest

- Federal and State Police Raid Three Homes in Atlanta Leading to One Arrest Amid ‘Cop City’ Investigation (February 8, 2024)

- One Year Since Tortuguita’s Killing: A Reflection on our Coverage of the Movement Against ‘Cop City’ and the First Eco-Activist Killed in the US (January 18, 2024)

- ‘Cop City’ Defendant Victor Puertas Has Been Held For Months Without Trial, but His Community Hasn’t Forgotten Him (November 26, 2023)

- No Charges For Georgia Troopers Who Killed Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Terán (October 6, 2023)

- Over 60 People Indicted on RICO Charges in Atlanta, Allegedly Promoting ‘Anarchist Ideas’ (September 5, 2023)

- Indigenous Climate Activist Victor Puertas Remains in Custody Despite No Indictment (July 26, 2023)

- 6th ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action – Unicorn Riot Coverage

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 8: Youth Rally; Atlanta Police Vehicles Torched (July 2, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 7: Cadence Bank ‘Drop The Loan’ Protest, Panel on Overpolicing (June 30, 2023)

- Clergy Demand Release of Indigenous Climate Activist Victor Puertas from ICE Detention (June 29, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 5: Cadence Bank Loan Protest, ‘March For the Forest’ (June 29, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 4: Rally to Reopen Intrenchment Creek Park (June 27, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 3: Bike Ride/Rally, Signature Gathering, Discussing Movement History (June 26, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 2: Rematriating Mvskoke Land; Hardcore Benefit Show (June 25, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Begins: Day 1 (June 24, 2023)

- ‘Their Overreach is Sowing the Seeds of Their Undoing’: Forest Defender Speaks from Bartow County Jail (June 20, 2023)

- ‘Cop City’ Protesters Visit Nationwide Insurance (June 14, 2023)

- Atlanta City Council Approves $67 Million in Public Funds for ‘Cop City’ (June 6, 2023)

- Atlanta Solidarity Fund Organizers Granted Bond (June 2, 2023)

- Three Atlanta Activists Arrested, Home Raided Over Bail Fund (May 31, 2023)

- ‘Don’t Forget Us’: Forest Defenders Confront Horrors of Life in DeKalb County Jail (May 30, 2023)

- ‘Cop City’ Panel Member Posted Slurs Online, Archived Tweets Indicate (May 18, 2023)

- ‘We Do Not Need a School for Assassins’: Hours of Public Comment Unanimously Against ‘Cop City’ (May 16, 2023)

- Three Face Felonies for Allegedly Flyering Near Home of One Georgia Trooper Tied to Killing of Forest Defender (May 8, 2023)

- One Granted Bond, Two Denied Pretrial Release: Forest Defenders Appear for Preliminary Hearings (May 4, 2023)

- No Gunpowder Residue Found on Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Terán According to DeKalb County Autopsy (April 21, 2023)

- Eight Remain in Jail from March 5 Weelaunee Forest Raid, 15 Released (March 24, 2023)

- Behind the #StopCopCity Domestic Terrorism Warrants (March 21, 2023)

- An Historic Direct Action in a Forest Outside Atlanta (March 18, 2023)

- Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Terán’s Independent Autopsy Report Released at Press Conference (March 13, 2023)

- Police Raid Atlanta Forest After ‘Cop City’ Opponents Overrun Security Post (March 5, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Begins in Atlanta (March 4, 2023)

- ‘Tortuguita Vive’: A No-Compromise Movement Responds to Police Killing a Forest Defender (February 27, 2023)

- Atlanta Activists Say Prosecutors Plan to Indict them on RICO Charges (February 25, 2023)

- ‘Community’ Committee Cheers Police Violence as Authorities Repress Resistance to ‘Cop City’ (February 24, 2023)

- Supporters of ‘Cop City’ Opponents Rally in Philly (February 24, 2023)

- Minneapolis March Connects Roof Depot Demolition Resistance to the Atlanta Forest (February 21, 2023)

- Atlanta PD Releases Bodycam Footage from Deadly Jan. 18 Forest Raid (February 8, 2023)

- Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Terán’s Family Seeks Transparency in Police Killing (February 7, 2023)

- City of Atlanta and DeKalb County Announce ‘Agreement’ Amid Growing Opposition to Cop City (January 31, 2023)

- Marches and Vigils Across the US Respond to the Police Killing of Forest Defender Tort (January 22, 2023)

- Protester Shot and Killed by Officers During Raid on Atlanta Forest (January 18, 2023)

- Blackhall Intensifies Destruction of Weelaunee People’s Park in Atlanta Forest (January 16, 2023)

- SWAT Teams Attack Atlanta Forest Encampments, Activists Charged with ‘Terrorism’ (December 18, 2022)

- [Mini Doc] Defending the Atlanta Forest: Behind the Movement to Stop Cop City (Oct. 9, 2022)

- “Cop City” General Contractors’ Offices Attacked (May 19, 2022)

- Police Raid Atlanta Forest Occupation (May 18, 2022)

- Atlanta Fights to Save Its Forest (May 14, 2022)

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: