Uganda’s Death Sentence on its LGBTI+ Communities

For the first time since 2005, a man may be sentenced to death in Uganda. Uganda has recently joined eleven other nations that retain the death penalty for same-sex relations. Despite some marked progress in Africa around its treatment of LGBTQ+ people over the past few decades, this is a staggering setback.

The new legislation has only inflamed ongoing concerns about human rights issues in the East African nation, spurring an overwhelming global condemnation from the likes of Amnesty International and the World Bank. Despite significant pressure, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni is stalwart on the new law. The drawbacks the leadership is willing to withstand during its process of victimizing peripheral communities are severe, both economically and diplomatically. This stubborn attitude in the face of potentially disastrous consequences draws up broader cultural and religious questions that underpin this obsession with punishing homosexuality.

This is a Commentary of Uganda’s newly introduced Anti-Homosexuality Act, and its wider context both historically and politically.

The Death Sentence

On August 18, 2023, a 20-year-old Ugandan man was charged with “aggravated homosexuality” for the first time under the country’s newly introduced anti-homosexuality act. That man is accused of having “performed unlawful sexual intercourse” with a 41-year-old, and despite the charge sheet not clearly specifying why the act was considered “aggravated,” the charge has been maintained by prosecutors. This distinction means that under the new legislation, the offense can be punishable with a death sentence. As Justine Balya, the suspect’s lawyer, argues, the act explicitly contradicts multiple fundamental rights within Uganda’s constitution: the right to non-discrimination under Articles 20 and 21, and the right to dignity under Article 24.

This man is reportedly the first to receive the specific charge of “aggravated homosexuality”; however, he is not the first to have come under the weight of the 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act. On August 19, four people, including two women, were reportedly arrested in a massage parlor in the district of Buikwe. This came after a tip-off from an informant. As well as this, according to Adrian Jjuuko, the Director of the Human Rights Awareness of Promotion Forum, his organization “documented 17 arrests” in June and July related to the newly introduced bill. This draconian act, its implementation, and the subsequent victimization of LGBTI+* people have been ongoing, and the potential of a state execution for the first time in Uganda since 2005 plainly illustrates just how unprecedented the prescribed punishments truly are.

*LGBTI+ is the preferred term in Ugandan communities.

Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2023

Uganda’s President, Yoweri Museveni, originally hesitated in his support of the Anti-Homosexuality Act. On April 20, 2023, he refused to sign the bill into law despite 387 of the 389 legislators voting and almost all of the parliamentarians in his party supporting the bill. It is worth noting, however, that after the bill was originally rejected by the President, a spokesman for Museveni clarified that “Museveni is not opposed to the bill’s punishments.” Likely fearing the inevitable international backlash and withdrawal of economic privileges, he waited for parliament to somewhat water down the bill.

On May 29, 2023, the bill was signed into law, becoming one of the harshest anti-LGBTQ+ laws in the world. The bill was widely received with applause among extremely vocal church leaders and a majority evangelical-Christian population. Parliamentary Speaker Anita Among rejoiced in her belief that the new law will “protect the sanctity of the family.”

The new law typically recommends life imprisonment for same-sex intercourse. However, in what authorities deem exceptional cases, “aggravated homosexuality” can carry the death sentence, as has been deliberated in the recent case. Repeat offenses, the transmission of terminal illness, or same-sex intercourse with a minor, elderly person, or disabled person all amount to the definition of “aggravated” under the new law. Additionally there is a prison sentence of up to 20 years for “promoting” homosexuality, drawing widespread concern for many LGBTI+ activists in Uganda. Another element of the bill requires Ugandans to report suspected homosexuals or those infringing on the new law, as has already happened in the instance of an informant reporting four people in Buijkwe.

Direct Human Consequence

A group of civil society groups in Uganda known as the Strategic Response Team (SRT) has reported hundreds of incidents that violate human rights law since the introduction of the bill. Videos have been spread across social media of increased hostility and violence towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people across Uganda. The SRT claims to have recorded over 300 human rights violations since the bill was signed into law. The group has also submitted a list of 50 verified cases to a judge to try and create an injunction against the law. 30-year-old transgender Ugandan man Nash Wash Raphael recounted in an interview with CNN his experience the day the bill became law and how, within 24 hours, his ankle was broken in a violent attack.

Some of the listed cases reported by SRT include instances of targeted evictions, wrongful termination of employment, threats of violence, incidents of mob “justice,” outings, and so-called “corrective” rape. In one horrifying video, which the SRT verified, a transgender woman is marched naked on the streets while a large crowd behind her jeers. A Ugandan politician, lawmaker, and vehement supporter of the newly introduced law, Asuman Basalirwa, argues these cases are simple fabrications. He claims the allegations are false and no one has been targeted.

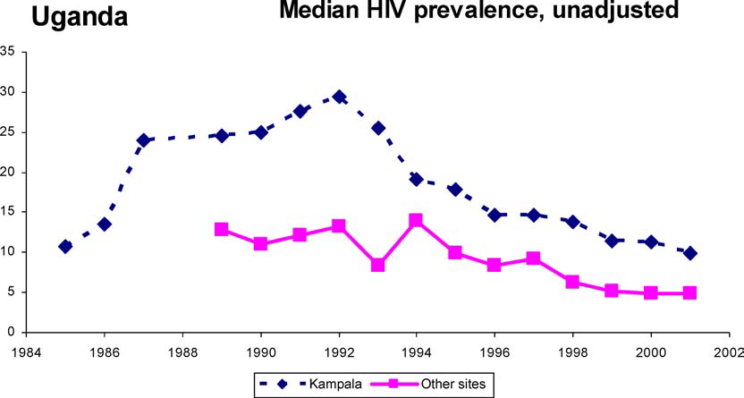

Another concerning development is the potential long-term escalation in the spread of AIDS and HIV in Uganda, creating a serious public health threat. According to a UNAIDS press release from May 29, 2023 “By 2021, 89% of people living with HIV in Uganda knew their status, more than 92% of people who knew their HIV status were receiving antiretroviral therapy, and 95% of those on treatment were virally suppressed.” The fears around association with the LGBTI+ communities in Uganda created by the new act potentially mean fewer and fewer HIV infected people will seek treatment so as not to be suspected by authorities or potential informants. The statement also included the aim of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030, a long-held goal that is now under threat of derailment. The U.S. and UN have warned that progress in tackling HIV is in “grave jeopardy” after Museveni approved this new bill. The threat to public health is just one of the many grievances held by leading organizations internationally.

Widespread Condemnation

The United States has been extremely outspoken against Uganda’s new Anti-Homosexuality Act. President Joe Biden called for an immediate reversal in May and labeled the new policies a “violation of universal human rights.” Biden further warned Uganda’s leadership, claiming Washington had considered “restriction of entry into the United States against anyone involved in serious human rights abuses.” Uganda’s already fragile economy would be massively affected by the withdrawal of U.S. cooperation. The country benefits from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), enacted in 2000, which allows Uganda to access U.S. markets. AGOA provides Uganda and 35 other African nations with duty-free access to 1,800 products in U.S. markets. A highly valued asset to the Ugandan economy and its future growth.

The U.S. is far from alone in its negative reactions; the EU, the UK, human rights groups, the World Bank, the Global Fund, UNAIDS, and many LGBTQ+ organizations have objected to the law. Of those, the World Bank has proven particularly important, putting huge pressure on Museveni. The US-based lender stated that “our vision to eradicate poverty on a livable planet can only succeed if it includes everyone, irrespective of race, gender, or sexuality.” This came with the announcement that the World Bank was suspending new loans to Uganda despite “remaining committed to helping all Ugandans.” The reaction to this withdrawal has been extremely negative from the Ugandan leadership. Museveni accused the World Bank of trying to “coerce” the government and taking to social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter, to explain that Uganda would develop “with or without loans.” Junior finance minister Henry Musasizi told parliament that the government plans to revise budgets for the period between July 2023 and June 2024 with the incoming financial impact in mind. Museveni’s stubborn defiance and absolute refusal to revert the act meant the World Bank proceeded to withdraw, and the Ugandan shilling subsequently took its deepest dive in almost eight years.

An Appeal to Populism

President Museveni’s iron-willed resistance to succumbing to substantial economic and diplomatic pressure may seem surprising. However, the calculated political and populist strategy of vilifying a subsection of society to distract from genuinely pressing domestic issues is nothing new to the continent.

In February, the Kenyan Supreme Court ruled to uphold a lower court decision recognizing LGBTQ+ groups as having equal status. The courts also stated the government couldn’t lawfully refuse to register the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (NGLHRC), creating widespread backlash in Kenya. President William Ruto, along with many politicians and religious leaders, have heavily condemned the court’s decision. President Ruto has, similarly to Museveni in Uganda, appealed to the populism of his nation’s widespread homophobia, claiming in a speech on February 24, 2023, that he can be trusted to protect the nation’s culture and traditions and stating, “I am a God-fearing man; we cannot allow men to marry fellow men.”

President Samia Suluhu Hassan of Tanzania, affectionately called “Mama Samia,” also shares these sentiments. In March 2023, she told university students that “human rights have their limits.” Another African nation in which the popularity of homophobic rhetoric is illustrated is Nigeria, where same-sex relations are also illegal. A 2017 report by NOI Polls showed that 90% of Nigerians supported the continued criminalization of same-sex relationships.

Much of this continent-wide sentiment is fueled by the unfounded populist notion that homosexuality is somehow culturally “un-African” and is rather a Western import. This idea is repeatedly regurgitated by religious leaders across much of Africa.

Contradicting Justifications for the Act

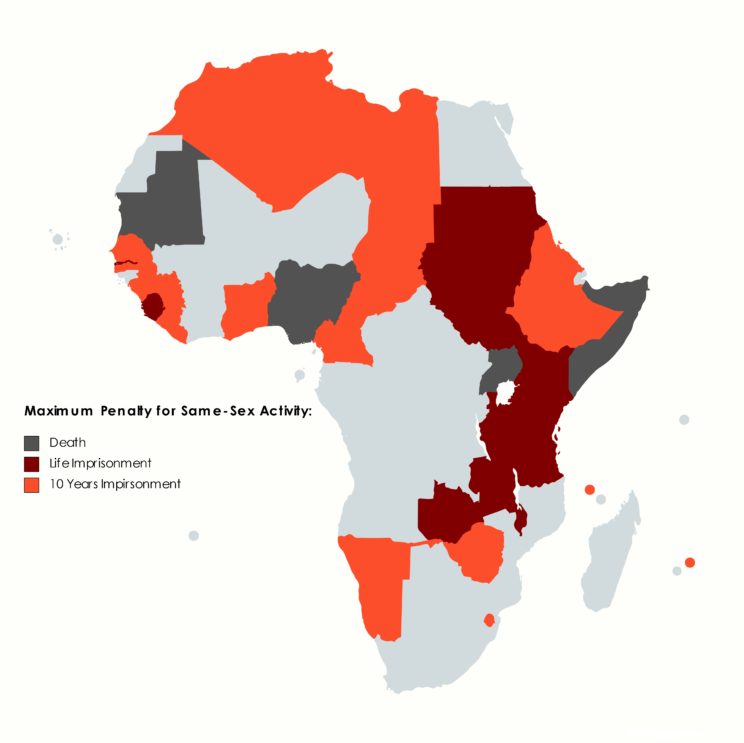

Homosexuality is criminalized in more than 30 of Africa’s 54 nations. It is, however, of course, appropriate to clarify that the criminalization of same-sex relationships isn’t exclusively African. Of the twelve countries that presently make the act punishable by death, four are African: Mauritania, Nigeria, Somalia, and, of course, Uganda. Most of the others are in the Middle East: Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and the United Arab Emirates. Brunei also has the capacity to punish same-sex relations with death. Much of the similarity in these state-sanctioned homophobic laws lies in religion, as it is one of the major overlying sentiments between orthodox Islam and evangelical African Christianity. This highlights one of the major contradictions in the argument that the opposition to homosexuality is culturally African and that alien Western influences are now trying to force a “homosexual agenda” down Africa’s throat. It is far more appropriate to say that homophobia is a Western import than homosexuality is. Religious leaders are one of the major mouthpieces against same-sex relations in Africa; however, Christianity itself is an import of European imperialism. According to a Pew Research Centre report, the Christian population in sub-Saharan Africa rocketed from 9% in 1910 to 63% in 2010.

As well as imported religious attitudes stoking homophobia, legal and constitutional remnants of European influence also contribute to generational homophobia. Homosexuality was already made illegal in Uganda, as well as other African nations, under a British colonial-era law that criminalized such activity and defined it as “against the order of nature.” According to British human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell, “Prior to Western coloni[z]ation, there are no records of any African laws against homosexuality.” To further this point, there are records from the 1600s of Azande warriors in Central Africa taking teenage boys in marriage all the way up until the 1800s, again demonstrating just how absurd the argument that homosexuality, as Robert Mugabe once said, is “un-African” and a “white disease.” Seen through these skewed lenses, attacks on LGBTQ+ people by leading politicians such as Presidents William Ruto, Samia Suluhu Hassan, and Yoweri Museveni are all perceived to be furthering African nationalism and pride.

Uganda Before the Bill

These sentiments are nothing new to Uganda either. Homophobia has been widespread for decades, and LGBTQ+ people have faced harassment and threats of violence long before this new setback. As recently as 2013, the “Kill the Gay Act,” — originally proposed in 2009 — was eventually passed. The bill originally included the death penalty, just as the new law does; however, it was reduced to life imprisonment by the Constitutional Court and didn’t become law until 2014. The fact that the 2023 Act retains the death sentence highlights how much LGBTQ+ rights have reverted over the past decade.

Despite adversity, the LGBTI+ communities in Uganda staged their first gay pride parade in 2012 and joined other marches in support of human rights generally. This would now be considered “promoting homosexuality” under the new law and draw a prison sentence of up to 20 years. The first march in 2012 came only a year after prominent Ugandan gay rights activist David Kato had been bludgeoned to death at his home in Mukono. The violent attack came after the now defunct Ugandan weekly tabloid, “Rolling Stone” (not affiliated with the popular U.S magazine) printed photos, addresses, and names of 100 homosexuals in Uganda on the front page, coupled with a banner that read “Hang Them.” The newspaper also alleged that homosexuals were aiming to “recruit” Ugandan children. These prior events illustrate that Uganda’s treatment of its LGBTI+ communities has not only been brutal, but that they not improving, and are arguably getting worse.

In Summary

Blatant contradiction within arguments for punishing homosexuality and the plain-face disregard of hundreds of human rights violations means that the political advantage of spouting populist homophobic rhetoric is unfortunately too appealing to leading figures in Uganda. It is important to note that President Yoweri Museveni has not budged on the new law, even in the face of such economic concerns. This means that top down threats from the West can do little to change attitudes towards homosexuality in Africa. Although withdrawal from the World Bank and U.S. markets has been applauded, its impotent attempt at reversing the new law means that local LGBTI+ communities and the work they do must continue and must be supported.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

![[Cover Photo] sourced via Creative Commons.](https://unicornriot.ninja/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Untitled-1.png)