As Border Protection’s Budget Increases, So Does Its Reach

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has been granted ever-growing policing power over citizens

Customs and Border Protection, the federal agency tasked with policing international borders in the U.S., is set to receive billions in additional funding after Congress passed its latest spending package. The agency, which has long avoided accountability, has a troubled history of law enforcement away from international borders – a practice that’s become steadily more common in recent years.

Motivated by the recent panic about immigration seen across media platforms, Congress voted to increase Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) budget as part of a newly passed $1.2 trillion spending package. The agency will receive a huge budget boost of $9.5 billion to hire 2,000 more agents, increase detention capacity by 22% (7,500 beds), and add 7,500 police-type vehicles.

The funding will also provide $850 million for boats, aircraft, and drones along with $650 million for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to address overcrowding in CBP holding facilities–a boon to the private prison industry.

For the last two decades, under powers granted after 9/11 and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), CBP has slowly been given ever-increasing powers to police U.S. citizens. Due to a growing number of interactions, many have been bringing attention to these seemingly overreaching authorities on social media.

Videos have been popping up on various platforms of U.S. citizens being questioned by CBP with increasing frequency. The frustrations of U.S. citizens are palpable when considering that many of the checkpoints are nowhere near the border. Disputes over what is and isn’t legal for agents to ask or do often lead to altercations – a concern for an increasing number of people.

While the Supreme Court has affirmed that CBP can stop you at a checkpoint and ask if you’re a citizen, you are not required to respond. But refusing to answer questions often leads to further questioning and prolongs detainment.

Agents wrongfully assume the rulings grant them law enforcement powers over U.S. citizens. Citizens who push back against border agents can find themselves in heated discussions, physical confrontations, or arrested on charges of assault or resisting arrest.

And while CBP checkpoints have been affirmed in the courts, their policing has expanded beyond citizenship checks to include helping local, state, and other federal agencies suppress protests.

During the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020, DHS, CBP, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents were deployed around the country to presumably help police address the protests. A leaked unofficial memo to then-Senator Kamala Harris obtained by The Nation revealed the extent of DHS actions outside of its duties. According to the document, DHS officers deployed to over 50 cities between May 20 and June 10, 2020.

More recent actions by CBP in a local law enforcement capacity have also raised eyebrows. During the mass shooting in Uvalde, TX, a large number of CBP agents were present – including a long-range sniper and the Border Patrol Tactical Unit (BORTAC). While a BORTAC team was ultimately responsible for ending the attack at Robb Elementary, CBP’s presence has only added more questions to an already grossly mishandled response to a school shooting.

Though BORTAC has been around since the 1970s, and has often worked with the Drug Enforcement Agency, it is typically only involved in immigration-related actions such as Operation Reunion – the April 2000 raid that led to the return of Elian Gonzalez to his family in Cuba.

In critical situations, it’s not uncommon to see federal agencies support local law enforcement. We see them help conduct manhunts, solve murders, and even stop crime rings on a local level. But in recent years CBP has been a growing presence in domestic law enforcement.

Blurring the Line

In addition to border patrol checkpoints, agents now patrol neighborhoods and communities with what DHS calls ‘roving units.’ However, CBP responding to civilian calls sparks questions about federal agencies operating locally and taking on police work.

One recent example involved a chase with a person in an alleged stolen van that, according to CBP, resulted in a crash that killed the suspect. The incident occurred about 7 miles from the nearest border with Mexico and along the California-Arizona border.

“On March 8, 2024, at approximately 11:15 a.m., the U.S. Border Patrol El Centro Sector communications center broadcasted that a stolen vehicle, described as a white Dodge Caravan, was reportedly seen near the California Department of Food and Agriculture Station on Interstate 8 (I-8) in Winterhaven, CA.”

Customs and Border Protection Press Release (3-22-2024)

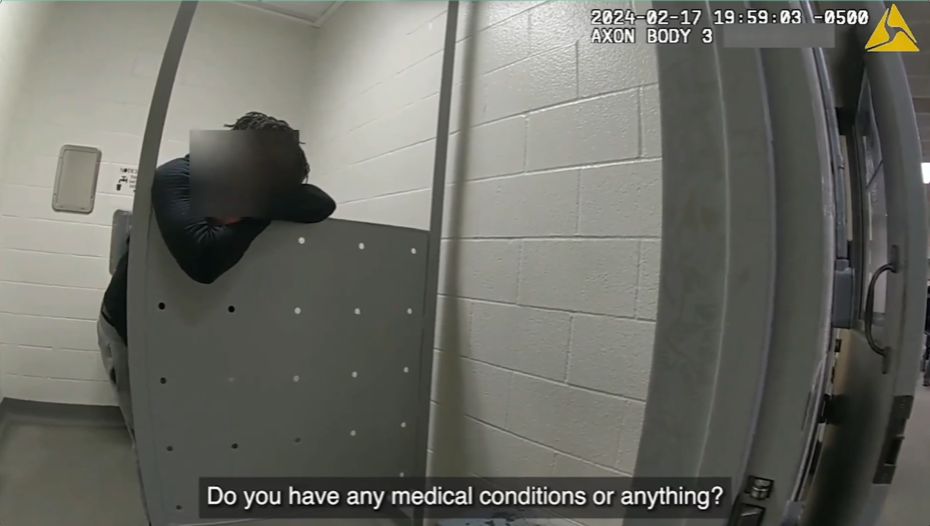

In another recent case, a U.S. citizen died by suicide in a CBP detention facility after being arrested by the agency miles from any international border. The truck driver reported being suicidal and asked to speak to his mother while being placed in detention. He allegedly hanged himself with his jacket by attaching it to a partition in the cell where he was the sole detainee.

Division of Powers

When local law enforcement needs federal assistance it is typically done by request because policing power is reserved for agencies under state and local governments. Several Supreme Court decisions have affirmed that local and state governments cannot be expected to enforce federal law. But, just as local law enforcement can’t enforce federal law, federal agencies aren’t permitted to enforce local laws either.

“The division of police power in the United States is delineated in the Tenth Amendment, which states that ‘[t]he powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.’ That is, in the United States, the federal government does not hold a general police power but may only act where the Constitution enumerates a power. It is the states, then, who hold the general police power. This is a central tenet to the system of federalism, which the U.S. Constitution embodies.”

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute

The founders’ reasoning for these separate powers is the same as for the overabundance of federal law enforcement agencies:to limit unchecked power. These fragmented systems are common throughout the U.S. federal government. But this separation of powers hasn’t translated to accountability for CBP or their operations in interior law enforcement.

UR Investigation: Learn How Minnesota’s HIDTA Launders Surveillance Requests thru Federalized ‘Drug War’ Unit

Lack of Accountability

In a report released last year, the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) highlighted the problematic nature of how CBP operates. The report emphasized how CBP’s broad authority poses serious threats to citizens and non-citizens alike and how the agency’s power could be dangerous in the hands of someone who wanted to control public discourse. The report also highlighted many of CBP’s capabilities and how they’re used against U.S. citizens.

“CBP collects data from thousands of travelers’ cell phones every year and stores it in a database that about 2,700 personnel from the Department of Homeland Security can search without a warrant. CBP also buys a vast amount of cell phone location data from data brokers and collects DNA from asylum seekers to be stored in an FBI database. The agency has used its surveillance powers and access to classified databases to target activists, humanitarian workers, immigration lawyers, congressional staff, and journalists.”

Katherine Hawkins, Project On Government Oversight (2023)

The stories as they’ve been reported in the news when compared against data suggest a broad lack of accountability.

And that lack of accountability extends to their checkpoint operations. In 2022, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report titled, ‘BORDER PATROL: Actions Needed to Improve Checkpoint Oversight and Data.’ The report highlights how CBP points to the high number of seized drugs at checkpoints while also exposing that most of those seizures are with small amounts of marijuana and those in possession of it are U.S. citizens.

“Border Patrol seized drugs in about 17,970 events at checkpoints. GAO found that most drug seizure events involved only U.S. citizens (91 percent), of which 75 percent involved the seizure of marijuana and no other drugs.”

GAO report (2022)

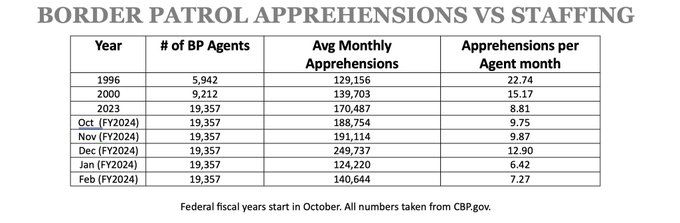

In addition to the manipulation of data in reports sent out to news media regarding immigration numbers, CBP’s press releases often lack context. Using 2023’s end-of-year reports, CBP’s and DHS’s data show that ‘expulsions’ are counted under ‘encounters’ alongside ‘apprehensions’ thus increasing the total number of migrants by more than 500,000. Data also show that more than half of all migrants ‘encountered’ or ‘apprehended’ were removed or returned.

“GAO found that while Border Patrol data on apprehensions and drug seizures were generally reliable, certain other checkpoint activity data, including on apprehensions on smuggled people and canine assists with drug seizures, were unreliable.”

GAO report (2022)

While the GAO found myriad issues with CBP practices and reporting regarding checkpoints, there are many other areas where they need more accountability. From detentions and the treatment of detainees to reporting accurate numbers at the border and reporting crimes committed by CBP agents while on duty, the lack of accurate data is a consistent problem. And despite having guardrails in place, efforts to implement and enforce any oversight still need to be made.

“Border Patrol established the Checkpoint Program Management Office (CPMO) in 2013 to oversee checkpoint operations. However, Border Patrol has not demonstrated a sustained commitment to ensuring that CPMO carries out its checkpoint oversight activities or held CPMO accountable for implementing these activities.”

GAO report (2022)

With the help of Border Patrol unions and far-right personalities, the agency provided partial data to frame a narrative using data points such as ‘+2 million encounters’ at the border without clarifying what that means. That the number includes people who may have been encountered multiple times and people who have been removed and returned to their home countries should be noted, yet it isn’t.

As CBP is increasingly impacting the lives of U.S. citizens – oftentimes more so than so-called illegal immigrants – the budget increase will likely just make it easier for them.

Cover image composition by Dan Feidt. Source: USCBP Flickr (public domain). Caption: “U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers with the Office of Field Operations stand their posts as they support security operations of the 59th Presidential Inauguration in Washington D.C, January 19, 2021. CBP Photo by Brian Sowards.”

Additional Resources

- GAO Report, “Actions Needed to Improve Checkpoint Oversight and Data,” 2022 (5 MB PDF)

- Leaked Memo to Sen. Harris re DHS & Protests, June 5, 2020 (3.5 MB PDF, re-compressed & OCR)

- Homeland Security Office of Inspector General, “DHS Had Authority to Deploy Federal Law Enforcement Officers to Protect Federal Facilities in Portland, Oregon, but Should Ensure Better Planning and Execution in Future Cross-Component Activities,” April 16, 2021 (2.6MB PDF)

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: