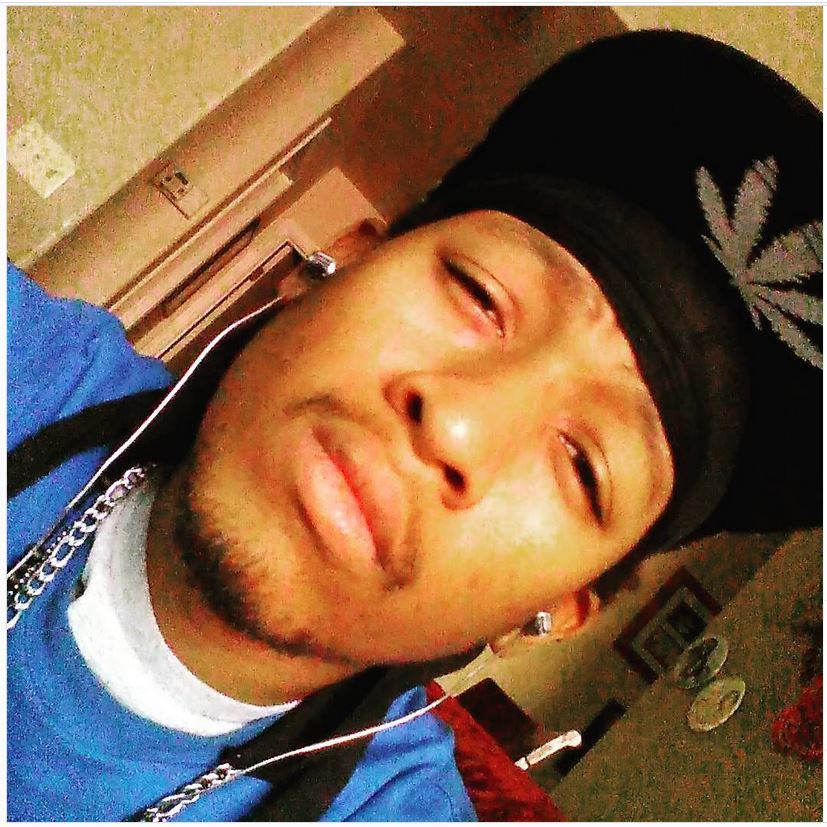

The Death of Justin Crook, aka J-Mac Tha Coldest, in the Pima County Jail

Tucson, AZ – In the early hours of May 30, 2021, Justin Crook had a seizure on his way home from work. It was after midnight, and Crook had called a Lyft to drive him home following his closing shift at a downtown Tucson restaurant. Crook, who suffered from epilepsy, sometimes forgot to take his medication and trips to the emergency room were a regular part of life.

Content warning: This article contains graphic images of law enforcement violence.

The Lyft driver called an ambulance as Crook convulsed in the back seat. When Tucson Police (TPD) officers arrived on the scene, they ran Crook’s name, found he had a warrant for a probation violation and several misdemeanors, and arrested him. By the time Crook got to the Pima County Jail, his body was covered with bruises and he was bleeding from his face and wrist. Reports indicate that he may have been tased by officers twice in the struggle.

Less than 24 hours later, Justin Crook, aka J-Mac Tha Coldest—29-year-old rapper, father of a 4-year-old daughter named Jazlin, brother to a twin sister and two younger brothers and son to loving parents—was found dead in cell #13 of the Pima County Adult Detention Complex. By the time medical workers got to him, his body was already stiff and cold—another life claimed within the jail’s cold walls of cinder block and iron.

This year alone, ten people have died in the Pima County Jail—more than in any single year in at least the last decade, according to information released by the Pima County Sheriff’s Department (PCSD) and a Reuters investigation. Although COVID has contributed to the rising death toll, only three of this year’s deaths have been attributed to the virus. It is impossible to know whether those individuals would have died had they remained outside state custody, however a study last year found incarcerated individuals to be five times more likely to contract the virus than those on the outside.

Since Crook’s death, the Pima County Sheriff has not made public any efforts to address the conditions at their jail that have led to so many deaths. “They acted like it was my fault that my son was dead,” said Jennifer Graham, Crook’s mother. Now, Graham and others who have lost family members in the jail this year are coming together to support each other and push back against the violence inflicted on their families.

“Once I realized that he didn’t die from what I thought he died from,” Graham said, referring to her son’s seizure condition, “then I realized that they did something to my child or they allowed something to happen to him.”

On Saturday, November 27, the group of about 50 family members and their supporters gathered in front of the Pima County Adult Detention Complex to hold a vigil in memory of their loved ones and to demand change. The group held banners reading “Jail shouldn’t be a death sentence,” “No more lies, no more deaths, we miss our kids!” and “Can’t spell coward without C.O.”

As is the case with most people who die within this country’s sprawling apparatus of jails, prisons and detention centers, the details of Crook’s death remain opaque, the role of government agents in his death obscured behind legalistic and bureaucratic jargon. “I’ve seen so many cases thrown under the rug,” said Graham, “Especially, my son, he’s African-American. I mean, let’s not even sugarcoat it.”

“I’m still lost,” said Jamila Jackson, a longtime friend of Crook’s. “I just keep thinking, ‘how could this be real?’ Not Justin. Not J-Mac Tha Coldest.”

More than anything, Crook’s family and friends say they want answers, but those answers have not been forthcoming. Despite the desperate cries against forgetting emerging from those who loved him and hold his memory dear, it appears Crook’s death may soon become another meaningless entry in a datasheet somewhere.

As the family sifts through their fragmented memories and the enigmatic tangle of evidence in his case, a portrait emerges of a human life stamped out too early, of forestalled ambitions and wasted dreams. Although real answers remain out of reach, the pieces can be carefully examined, one after another, in hopes of making whole what was so quickly torn apart.

Jennifer Graham holds a photo of her son Justin Crook and her granddaughter Jazlin. (Source: Gully Theravine for Unicorn Riot)

Related: Harrowing Footage Shows Man’s Last Days Before Dying in Jail

“I want to go home bloody so I can press charges.”

The autopsy report in Crook’s case found evidence of numerous “blunt force injuries” that substantiate Crook’s statements to medical staff about having been beaten by TPD officers during his arrest. Details of his arrest are uncertain and TPD refused to release any information about the incident in a timely manner.

Crook’s family members report that when he had seizures, he would come out of them disoriented and upset, a situation that could contribute to a dangerous encounter with the police if they respond, as they so often do, with aggression rather than medical care.

“The driver called 911 to get me help and they picked me up on a warrant,” Crook told jail staff, according to jail records. “I was out of it from the seizure. You know how you come out of a seizure kinda crazy!”

At the time of his death, Crook had a black eye, two “punctate red abrasions” on his right cheek and two more on his shoulder, and several bruises on his head. His body and arms were covered in abrasions and bruises, including scrapes on his wrists and a 6 inch by 6 inch V-shaped bruise on his abdomen. But, according to the Medical Examiner’s findings, none of this evidence of violence is what actually killed him.

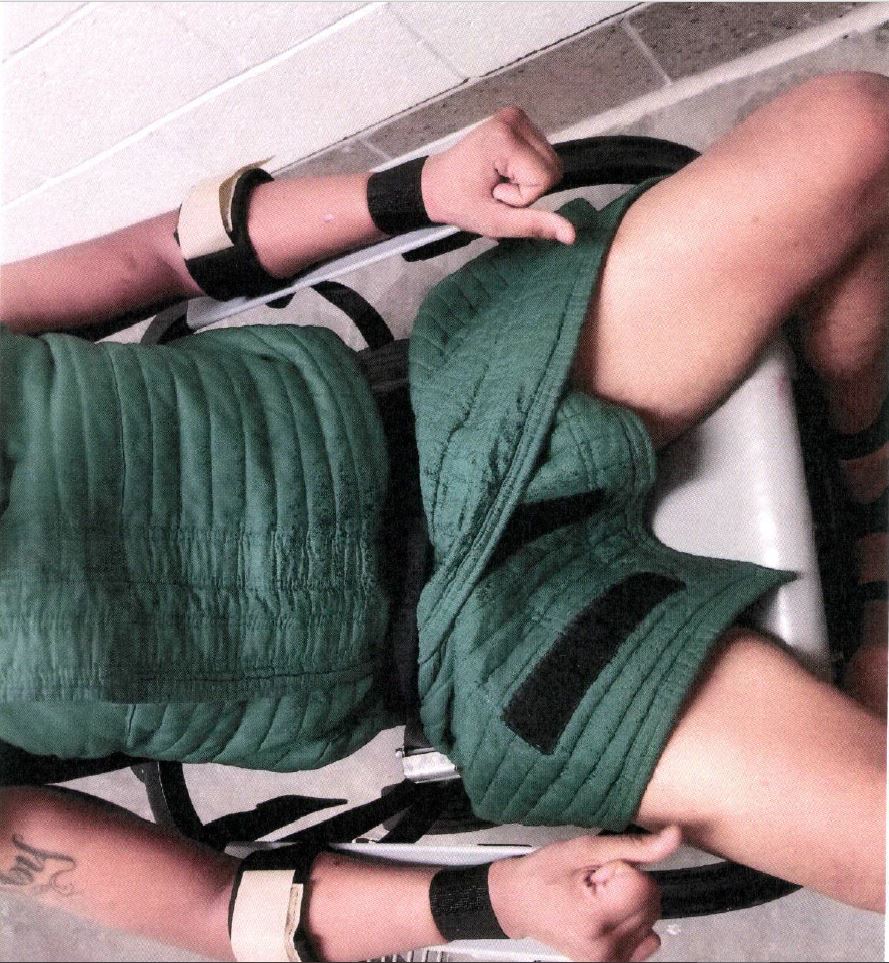

Jail medical reports say that Crook was “brought in as combative, in a WRAP, by TPD and refusing to follow the instructions of custody staff.” A WRAP is a full body restraint device patented and sold by Safe Restraints Incorporated, a California-based company. The device is marketed as a “safe” and even “comfortable” alternative to hog tying, where a person’s arms are tethered to their ankles behind their back.

The Tucson Police Department adopted the WRAP system in December 2020 in response to public outcry following the deaths of Carlos “Adrian” Ingram-Lopez and Damien Alvarado, both of whom were killed by police while restrained in 2020. While Ingram-Lopez was double-handcuffed and pinned down by police when he died, Alvarado was restrained using a “Total Appendage Restraint Procedure” or TARP, also known as hog tying.

TPD marketed their new restraint system as a humane alternative to their previous methods and as demonstration of the department’s commitment to reform. But the WRAP restraint system has been long implicated in numerous in-custody deaths, including the 2018 death of Earl McNeil in San Diego County, CA, Steven Hankins in Concord, CA and Eugene Jimerson Jr in Hayward, CA.

In medical records from the jail, staff wrote that Crook “presents as agitated/aggressive and is paranoid about staff wanting to harm him, and perseverates on wanting to press charges and the events leading up to the situation.”

The reports also show that Crook refused to have his wounds cleaned by staff because he wanted to preserve evidence of having been beaten by police. Crook “refused each time stating it was his right and that he need [sic] it for evidence against custody,” staff wrote in the report. Staff later wrote that Crook said, “I want to go home bloody so I can press charges.”

Records also indicate that jail medical staff may have been performing their interview and treatment in the presence of jail staff or police who Crook did not trust or from whom he feared violence. “I won’t let you touch me until they [custody staff] are gone,” the report quotes Crook as saying.

Despite noting in their earlier reports that Crook seemed to be under the influence of methamphetamines, jail staff took no steps to enact any overdose prevention protocols in his case. In an email to Unicorn Riot, the PCSD explained that they took no detox or substance use precautions in Crook’s case because he refused medical treatment at the jail.

“Normally, an inmate identifies and cooperates with medical staff on substance use and withdrawal,” a representative of the PCSD said in an email statement to Unicorn Riot. “This is not the case as Mr. Crooks [sic] refused all attempts by medical staff to do an evaluation.”

The jail reports, mostly covering the period from 2 a.m., when Crook was brought to the jail, to 8 a.m. the same day, paint a picture of Crook as combative and uncooperative. “Current presentation is consistent with methamphetamine intoxication,” jail staff wrote in their report at 6:10 a.m. But surveillance camera footage from a few hours later shows Crook unrestrained and seemingly calm, changing into an orange jumpsuit at the request of guards and calmly walking with them through the halls to his cell.

At 11:47 a.m. on May 30, Crook was led unrestrained to Unit 4A, cell #13 and walked into the cell without resistance. In the footage, he appears to be talking normally to the guards and shows no signs of the agitated state one would expect from someone under the influence of a fatal dose of methamphetamines.

The PCSD said in an email that jail staff perform “rounds” every 20 minutes and that, according to their review of surveillance footage, jail staff checked on Crook at 2:12 a.m. and 2:33 a.m. Based on medical reports from the time of his death, Crook was likely already dead when guards performed these rounds, but did not notice or provide him help.

Despite the hours of surveillance camera footage and the dozens of pages of reports, for Crook’s family and friends, the mystery of his death remains. “There are a lot of dots that are not connecting,” said Sierra Lee, Crook’s friend. “And there’s no answers.”

“The Autopsies Say Nothing”

According to the medical examiner’s autopsy and toxicology reports, at the time of his death Crook’s body contained many times the average single dose of methamphetamines. According to these findings, Crook at some point consumed enough meth for the medical examiner to rule that he died of “acute methamphetamine intoxication.” If that finding is correct, the key questions become: When did he take those drugs and where did they come from?

The Pima County Medical Examiner ruled Crook’s death an accident. Graham doesn’t accept that explanation: “How do you overdose from methamphetamine intoxication when he was on their property for 30 hours? That makes no sense.” Although she doesn’t dispute that her son had issues with drugs, Graham says she doesn’t think the jail’s story adds up. “It’s just a lot of red flags there. Their stories are inconsistent. You know, they did not expect me to pursue this.”

As has been noted, information from autopsy reports is often manipulated to obfuscate the involvement of law enforcement in the deaths of those in their custody. In an interview with Perilous Chronicle earlier this year, Dr. Gregory Hess, Chief Medical Examiner for Pima County explained that autopsy reports prepared by his office do not take into account superseding conditions, such as the inherent dangers of incarceration, forced confinement within a congregate setting during a pandemic, medical neglect, or conditions of confinement.

“We’re just the cause of death folks,” said Hess. “We tell people what happened as factually as we can. So when people have questions about standard of care and whether things were done correctly, people can have those questions but it’s not usually us who’s opining about it.”

Autopsy reports in the case of Carlos “Adrian” Ingram-Lopez, who was killed by Tucson police in April 2020, initially found that he had died of “sudden cardiac arrest in the setting of acute cocaine intoxication and physical restraint.” A later, independent autopsy found that Ingram-Lopez died of “suffocation” and body camera footage clearly shows his slow suffocation by Tucson Police Officers who ignored him as he told them he couldn’t breathe.

The officers later resigned, but no criminal charges were brought against them. Autopsy findings in the case were used by the former Pima County Attorney, Barbara LaWall, to justify her refusal to indict the officers.

In the case of George Floyd, who was murdered by the Minneapolis Police Department in May 2020, an autopsy report was used to bring attention to the presence of drugs in Floyd’s system and a preexisting heart condition and away from the knee on his neck that killed him.

“They almost beat me to death”

Graham believes that her son’s death has something to do with an incident that occurred in the jail almost one year earlier, when Crook was arrested on a misdemeanor warrant and failure to appear at his court date.

“They ended up beating the crap out of my son,” Graham said. “Put him in the hospital.”

In May 2020, Crook was arrested after Tucson Police Officers responded to a call from Graham who was concerned about an argument Crook had gotten into with his girlfriend. “I just called them to go over and do a wellness check,” Graham said. When they arrived, officers found drug paraphernalia and arrested Crook on several misdemeanors including “disorderly conduct” and refusing to give his name.

Crook was released and, after missing his court date, Tucson City Court Judge Susan Shetter issued a warrant for his arrest. Crook was arrested three weeks later and incarcerated at the Pima County Jail.

Accounts of what happened next differ. According to Corrections Officer Fernando Amador, Crook, who he claimed he’d never spoken to before in his life, sucker punched him in the face without provocation. In response, CO Amador and several other officers “entered the room in attempt to secure that inmate to the ground,” according to incident reports obtained by Unicorn Riot. “CO Amador stated he struck the inmate a couple times in the face area,” the report reads. “Ultimately, a taser was utilized by another CO and they were able to get the inmate out of the cell and secure him into a restraint chair.”

Crook’s side of the story is harder to obtain as he did not author the many reports of the incident and has since died in the jail, taking his story with him. What does remain is an interview with Crook, conducted by an investigator with the PCSD. The recording, conducted shortly after the beating, is his only remaining testimony of the event.

In audio of the interview obtained by Unicorn Riot, Crook’s voice is tense, almost a whisper. His breathing is labored and he struggles to speak though a swollen mouth. He sounds exhausted, and his voice cracks with emotion. He repeatedly says that he is giving his testimony under duress, that he does not feel he has a choice, that he fears retaliation for what he says.

At one point, the investigator tells Crook to not worry about the guards and to just focus on telling his story. Crook replies, eerily, “It’s hard to do with the person who almost killed you standing right behind you.”

When asked what happened between himself and CO Amador, Crook admits to punching the officer as he opened the door of his cell. When asked why he did it, Crook says: “He said a remark about my dead friend.”

“I’m not a fucking punk,” Crook continues, “I miss my friend. I’m not gonna be cool with nobody disrespecting his presence. And I’m willing to die for that. OK? So I almost did.”

Surveillance camera footage of the incident obtained by Unicorn Riot shows Amador and a group of officers moving a detainee down the hall of Unit 1S and stopping in front of cell #3. As the jail cell door slides open, a hand emerges from the cell, punching Amador in the face. Amador and two other officers—C.O. Quijada and Corrections Sergeant Grimsey, immediately enter the dark cell, disappearing from direct view of the camera, while a fourth—CO Reyes—leads a detainee down the hall, securing him in another cell.

When Reyes returns, he stops in the doorway of the cell, staring intently inside, watching. He does not enter the cell. He makes no move to help the officers inside, as one might expect if a detainee were resisting. He fidgets with the cell door, adjusts his mask. Several times he seems to consider turning to leave. He remains at the cell door, staring. Over a minute later he disappears into the dark cell.

Six-and-a-half minutes after the officers initially enter the cell, they drag Crook out and put him into a restraint chair. A nurse approaches to check Crook’s vital signs, managing the body so recently damaged by her co-workers.

In the interview with Crook, despite being severely injured and certainly aware that he will face assault charges, Crook expresses no remorse for his actions. His voice, previously restrained and low, becomes strong as he describes his actions as well as the code to which they adhered.

“He disrespected my friend,” he says. “You think I give a fuck about getting beat up for that? It was the right thing to do.” “I’d do it again,” he says.

“What was your friend’s name?” the officer asks.

“Anthony Garrett.”

The officer repeats the name, “Anthony Garrett?”

Like a call-and-response, or a sacred invocation, Crook says the name again. “Anthony Garrett.”

Anthony L. Garrett, 24, was killed by security guards in June 17, 2019, at a business on East Broadway Boulevard where his ex-girlfriend worked. According to official accounts, Garrett had been involved in a domestic violence situation with the woman earlier that month and had gone to her work looking for her. During a gunfight with security guards, Garrett was killed.

In the recording, Crook’s voice cracks with emotion as he talks about his friend in whose honor he has brought upon himself so much suffering: “I just wanted my friend to know…I love you and miss you bro. Straight up.”

As a result of the altercation at the jail, Crook was charged with “Aggravated Assault on a Corrections Employee,” a class five felony. None of the officers involved were charged with crimes. In December 2020, Crook pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of “Attempt to Commit Aggravated Assault on a Corrections Employee,” a class six felony, and was sentenced to three years’ probation.

“I personally think he was too good for this Earth.”

Justine Crook, Justin’s twin sister, says she wishes she could have taken some of her brother’s suffering into herself. “You can tell when someone’s really sick,” said Justine, “and I felt like my twin was really sick.”

Mental health issues run in Crook’s family, and in adolescence he started showing signs of the mental illness and substance abuse he would wrestle with the rest of his life. Years later, he would be diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia as well as post-traumatic stress disorder.

In her hardest moments, Justine thinks her successes in life may even be attributable to the suffering of her twin, her mirror image and lifelong counterpoint in the world. “He took all the bad problems when we were in the womb,” Justine said. “He took everything bad.” Like a sponge that absorbed all her hardships, leaving her to succeed.

In the weeks before he died, Crook had been working a new job and writing music and trying to get his life on track for his daughter. “We got some blessings with this music shit,” said Crook in a text to his friend Dale Francisco, a Tucson hip-hop artist and producer who uses the alias Teknik, two weeks before he died.

“Been a long time coming but I think we can really jump off at least locally for sure,” Crook wrote. He told Francisco he had a notebook full of songs and asked the more established rapper to help him record an album: “I wanna work on my mixtape all year then release it in January. 10 songs perfected.”

Despite his mental health struggles and occasional problems with the law, Crook never stopped reading and never stopped rapping. “He could just sit there all day and read a book,” said Justine. “He was the smartest person I’ve ever known.”

“I personally think he was too good for this Earth,” said Justine. “I feel like God took him because he was way too good to walk this Earth.”

On the night of his death, Crook messaged his mom on Facebook, saying he was having a hard day. He was worried about his daughter Jazlin and an argument he’d gotten into with her mother. Graham could tell he was feeling down. “I told him, son tomorrow could also be a better day,” said Graham. “And so those were my last words to my son.”

Crook’s friends and family still don’t have the answers they need, and the institutions that ended his life remain unresponsive to their demands. Nevertheless, they find solace in their memories, in watching Crook’s daughter grow, in the support of others who have lost children to the jail, and in their efforts to seek justice in his case.

Graham and her husband have hired an attorney, Amy Hernandez, to investigate their case and filed a lawsuit against the PCSD in November.

A week after Crook’s death, Justine went to North Carolina to visit the ocean and to mourn the loss of her brother. As she sat on the sand, watching the waves crash onto the beach, she knew that from that point on her twin would be looking through her eyes and experiencing the world through her.

“You feel this twin?” she asked her brother aloud, watching the waves. “This is what life is about.”