The Different Facets of Gentrification in Greece and Beyond

Analysis for our ‘Gentrification in Greece’ Series

The closing of Exarcheia Square by the Greek authorities in August 2022 to build a metro station marked a significant blow to the historic district. As those who reside in sections of Athens, Greece face an onslaught of ‘development,’ this article provides analysis to this development and takes a deeper dive into the recent rise of gentrification in the second part of Unicorn Riot’s series from Greece.

Part 1 – Gentrification Endangers Historic Exarcheia Square

Part 3 – Altering Exarcheia From the Square to Strefi Hill: A Timeline and Film

In the modern digital times with global communication and outbursts of information, the power of the image and its aesthetics have been weaponized by authorities worldwide in attempts to create new unconsented normalities.

Globalization of capitalism and its mechanisms of enforcement, along with directives that emerge from think tanks with neoliberal alt-right agendas interconnecting through an international thread (as it became obvious with the example of Cambridge Analytica being behind both Brexit and Trump’s election), are giving authorities a global manual on how to impose and preserve their power. An ever-present keynote in these agendas is the term of gentrification. Used especially in its planetary form, gentrification offers a facelift for authority and a new illustrated cover for growth and progress whose false promises and disappointments have led to climate change, inconceivable inequalities and a global depression that only gets worse.

This article is an analysis piece reflecting lived experience, research and local perspectives written by an Exarcheia resident. The views and opinions expressed don’t necessarily represent those of Unicorn Riot.

Gentrification as a New Phenomenon

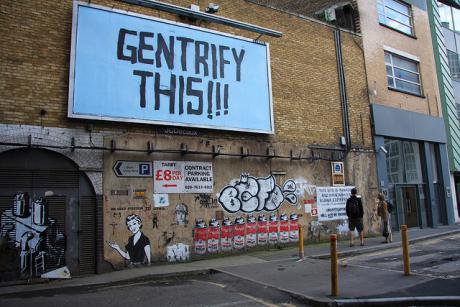

Gentrification was introduced as a term in 1964 by sociologist Ruth Glass when she tried to describe the rapid changes of the neighborhoods of London and the vast alterations that they brought to the social characteristics. Glass inverted the British upper class term ‘gentry,’ which is a step below nobility, into a negative term while observing the displacement of mostly blue-collared communities in the areas of Notting Hill and Islington by the wealthier middle class bohemian gentry population.

In the last decades, gentrification has become an omnipresent phenomenon in big cities globally. In Athens and throughout Greece, this phenomenon has been intensely visible over the last ten years.

To further understand these modern urban conditions, we should refer to some general characteristics and forms of gentrification. Locality is of the utmost importance and with it, a variety of forms should be thoroughly considered.

Speaking to different examples with different geographical or sociopolitical contexts, we can roughly note twelve core characteristics of gentrification:

- The commodification of social housing due to increasingly degrading conditions

- The phenomenon leads to the growth of slums or informal settlements because of the displacement in the ever-growing urban tissue

- Suburban expansion and development in peripheral areas, especially with fast-track ‘growth’ policies allowing land title regularization and de-normalization permitting the absolute reign of the rental market and home ownership by real estate funds or trusts.

- Gentrification does not have exclusively class characteristics since its causes and effects have not only a financial face but also cultural, aesthetic, social, political and repressive ones. Its temporality also provides a different process in each place which may not escalate around an economic axis.

- The gentrifiers have a less deeply rooted relationship with the neighborhood, its history and sociopolitical background, putting their armies of architects, builders and interior designers to mutate, perhaps permanently, entire parts of the city.

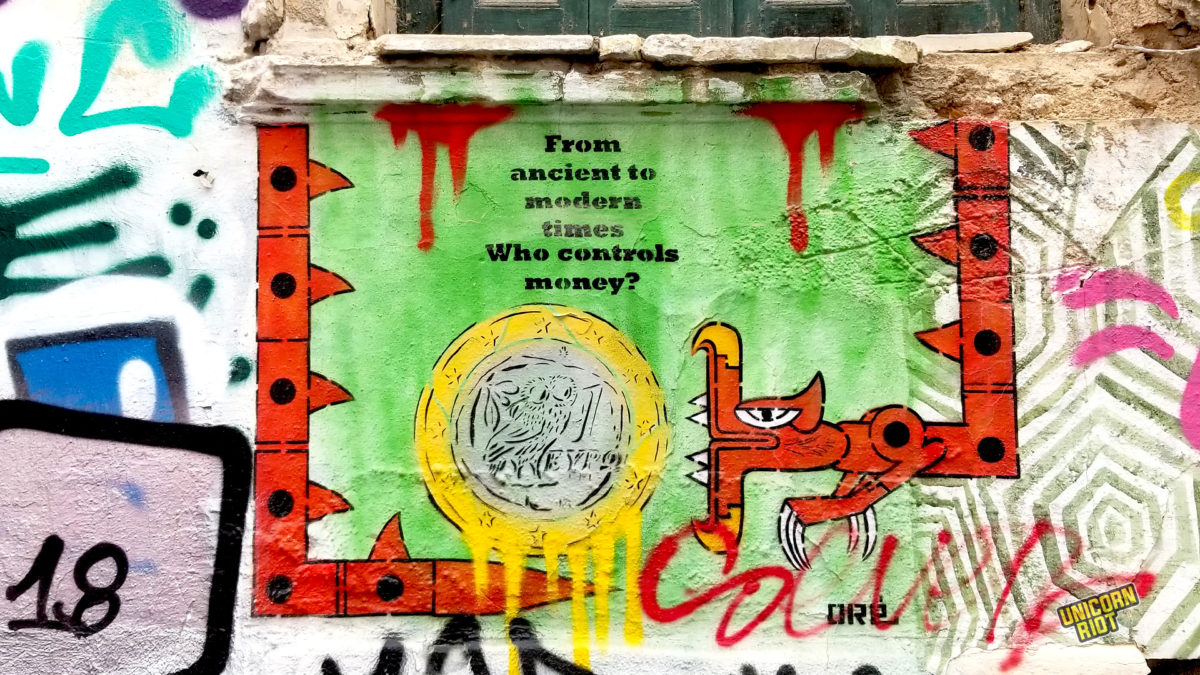

- Gentrification cultivates cultural appropriation by market state, ‘folklorization’ of cultural aspects especially where ‘touristification’ is intense, creating a museum or gallery-like approach of the public space. Artists are pivotal in these situations and aid through aesthetics to valorize the mundane and the meaningless. (For example, street art is repackaged for lobbies of new luxury apartment buildings.)

- Gentrification mostly does not stop, but changes phases. The landscape changes and the upcoming transformation of the neighborhood’s social character changes local politics, city planning and commercial needs, stimulating a wider gentrification.

- It spreads the commercialization of the public space and a panoptic surveillance over it, especially in new so-called “smart cities.” The upgrading of public space and services serves as a step toward a more controlled, sterilized, privatized hypothesis.

- Real estate, instead of a tool, becomes the regulator of access to housing and city planning. Rental and housing policies intensify displacement and exclusion of the locals. Real estate’s function is transmitted to previously irrelevant sectors such as finance and education etc. Real estate is not a labor sector, but a working sector as legal as gambling.

- Gentrification often revolves around communities which have the aura of authenticity. That authenticity appears as a meaning to fill the void of what can be considered a plastic neoliberal life and the notoriety of grittiness. Through commercialized aesthetics of the privatized individual, that authenticity is portrayed to the gentrifiers as an innocent guilt, or a forgivable sin, in their effort to touch the forbidden fruit without getting dirty. Through the lenses of a white spatial imaginary, the art world legitimizes the above since its dominant aesthetical regime identifies with gentrification aesthetics. Inclusion, diversity, or immigrant urbanisms become cheap opportunities or trends which offer a politically correct cover for racist reactionary organizations. So, in the end there is a destruction of the aesthetics of the neighborhood.

- Displacement has a huge psychological toll and impacts the living standard of the people who face it. Those displaced mostly try to move close to where they lived in order to retain personal, commercial or institutional ties that counter the economical or often racial restraints they face. This forces them into houses with inferior quality, less space and higher prices—a life less worthy of living. Exclusion of local populations is enhanced by the fact that in most cases “informal businesses” and local economies of neighborhoods based on solidarity, and not the laws of the market, become extinct for the regeneration process to take effect. (Crushing informal markets and unlicensed street vendors are often a sign of this trend.)

- Public green space and public transportation systems, especially the metro, are signs of gentrification in neoliberal cities. The privatization of recreation and health as ecological damage of the urban space turn them from commons for the people, as they should be, to commercial goods for profit and control. Social innovators, digital nomads and academics who approach these goods as a fertile ground to access funds, profit and to build careers have a short-term stay in the area producing a long-term gap leading to transient, abstract and socially faceless neighborhoods.

Forms of Gentrification

Gentrification seems to always wear a liberal smirk that embraces diversity, talking openly about white guilt, responsibility and equality. But in fact, it carries an empty liberal delusional mirror where others are fading under oneself and the meaning stops when it starts getting uncool and boring. Gentrification creates a progressive playground for the privileged until the game flexes in a new way.

As the above list of characteristics are deployed in various ways and intentions regarding locality and its interaction in the global canvas, we can also note different forms of gentrification. Scale and contextuality are pivotal for gentrification’s alterations. The forms include the size and the speed of growth, the racial, ethical, religious or cultural relationship of each of the populations, the segregation and decentralization that exists to different degrees, plus the social and financial infrastructures, that altogether with the above, dictate the city’s politics and planning.

Briefly put, gentrification is referred to in six forms:

- Perhaps the most recognizable is the new build gentrification through new homes and developments constructed in empty fields. Even if there is no displacement of the new upgraded neighborhood, it becomes gentrified.

- Rural gentrification which happens in rural places giving an ‘authentic’ ticket of living in nature.

- Super gentrification which appears mostly in big metropolises and in already heavily gentrified areas through further investments.

- Student gentrification where universities function as real estate holding companies, sometimes even turning entire cities into student consuming commercial zones. Often these entities benefit from tax-free status (Edinburgh, UK, Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts are good examples).

- Commercial gentrification where whole areas are turning into sterilized commercial avenues and trading places. (In the U.S., “big box retail” with very large square footage, supplants and displaces smaller locales, as Walmart expands near highways and old downtowns become abandoned and unviable. Eerie abandoned malls are testaments to the last wave of commercial gentrification.)

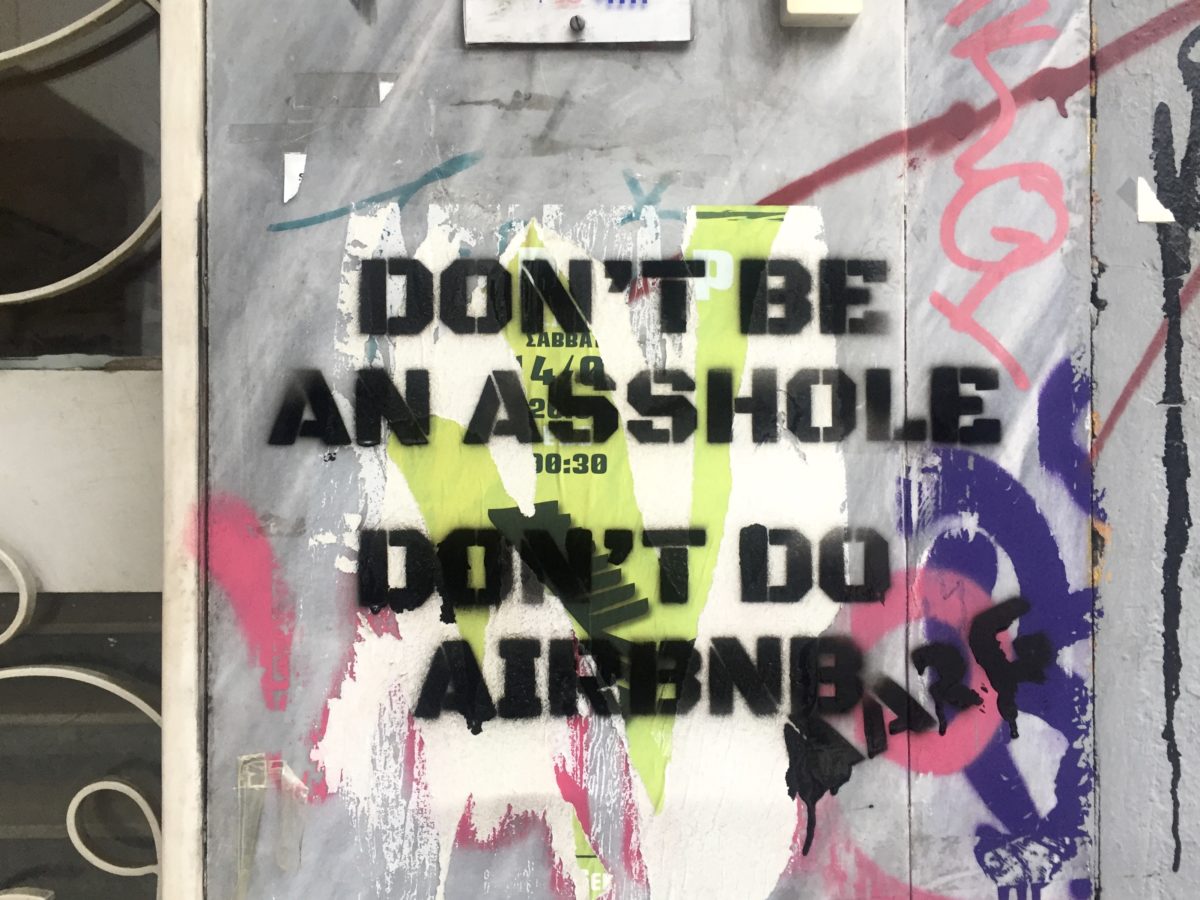

- Tourism gentrification, which as a plague invades every hidden inch of a city turning it into a huge hotel providing neverending exclusive services to the tourists, and misery and a sense of constant enslavement to the locals. (In recent years AirBNB has contributed to reducing affordable long-term rental options in many cities worldwide.)

“A cheap holiday in other people’s misery!” as the punk rock group Sex Pistols sang.

Touristification is aggressive and intensifying in Greece, leaving the country with an awful scar, especially in Athens and across the islands.

Finally ‘gentrination’ is the gentrification perceived on a national level rather than a neighborhood one. Being that there are words also about planetary gentrification, these phenomena are described as being interlinked, interrelated and on a global scale.

Further, green gentrification is an approach that describes how a closer proximity to passive or natural green space is accompanied with enormous housing prices.

Parameters of Gentrification – Toward a Panopticon

We should try to elucidate the phenomenon of gentrification by adding two important parameters.

The first parameter of gentrification is the mobility of the present societies. As the concepts of communication, information and technology continue to change in the digital era, distance and the relation that individuals keep with their place of origin has also changed. Financial globalization has forced sections of social sectors to be on a constant move—from tourists and digital nomads to immigrants and refugees.

These non-stop flows and their rising intensity create more fluid societies, often unstable due to the irrational inequalities that can spring from aggressive authoritarian government policies. This, in turn, leads to more opportunities of profit for the real estate companies and corporations. These companies benefit from the efforts to present whole areas as diminished and feed on economic and social instability, following the old recipe of turning misery into money.

The second parameter is the digital interface in which societies function, interlink and interact in the frame of the so-called smart cities. Maybe this approach of smartness hides a delicate unthinkable irony, but a smart city means in simpler words, urban digitalization.

Governance, labor, production and city planning are redirected through data-driven digital systems, platforms and services such as Google, Amazon or Uber, which drastically change the social, political and economic relations in and across cities.

San Francisco and Silicon Valley are both characteristic examples of thesis metamorphosis as they’ve been heavily gentrified for more than two decades now, leaving sterilized remains of meaningful pasts.

Gentrification is tightly coupled with ‘smart city’ trends, precarious employment based on smartphone apps, physical security and control of space imposed through digital systems like Amazon Ring cameras.

Surveillance and control are important elements rising through overinvestment in this digital mode of the gentrifying process. It’s not only the security cameras, the data mining, and the panoptic privatization of public space, it is also the furious assumption on behalf of the tech companies that they own the city. They don’t just want to draw value, but they seek dominion or domination over it. (The battle in Seattle saw Amazon prevail against a modest corporate worker ‘head tax’ in 2018; its supporters aimed to eject progressives from the city council.)

The city embodies a digital-friendly interface, and then authorities can utilize artificial intelligence to predict citizens’ behavior, prevent the unexpected and practice an algorithmic governance by creating controlled spaces of proximity or practicing strict social discipline with alert warnings on faceless mobile phones as it happened with the pandemic measures in Greece.

Learn more about the Minneapolis SafeZone, a smart city initiative aimed at ‘lifestyle offenders’

See our recent coverage of an anti-gentrification march in Philadelphia

Gentrification presents exactly this transition to the panoptic future and most importantly tries to bury all the public grounds in the city that the common people have ties to, those pockets which have cultivated dissent and protest, and provided the spaces for people who simply try to survive this mutation.. It is not by chance that the growth and progress which is promised to the gentrifier always means a new landscape of stores and services where time turns into value and meaning into commerce.

Sustainability, social justice and ecological proaction are the main promises in this illustrious tech driven pseudo-paradise. The last promise being of utmost importance since the neoliberal environment that these cities are anchored to in the last decades have caused an increase of instability and turmoil, a loud break of all kinds of social contracts and a possibly irreversible ecological catastrophe.

Gentrification is advertised as the exotic fruit by the natives, a promising growth, lifting to the face of empiric neoliberal cities, which crumble under the inherent vices of their leaders. Athens, after many years of a mainstream effort to break away from its Balkan, Eastern, mystified origin, is finally part of the West. Undoubtedly European with a heart of Euros, it’s now an accountable geopolitical player available to the appetites of the superpowers.

Strefi Hill and Exarcheia Square

This privileged relationship between Greece and the EU will ensure the panoptical character similar to the new Lofos Strefi (Stref Hill), and provide opportunity for their private interests to blossom. Strefi Hill is a massive hill located in central Athens with an integral importance to the Exarcheia neighborhood, which is increasingly threatened by gentrification. Just months ago, construction and security contractors from Unison, connected to Athens’ mayor and the Prime Minister of the country, began to fence sections of the hill off.

The reduction of the green element of the hill is not treated like another ecological error, but as a minor appropriate misdemeanor in the name of growth and prosperity. This sense of anthropocentric, ecologically hostile progress together with sustainability are the key illusions that gentrification tries to sell to its willing or unwilling clients without a receipt of freedom, of course.

In the beginning of August, engineers accompanied by numerous praetorians of the state, arrived and tried to work on Strefi Hill, but were stopped by residents and people from the Assembly Against Strefi Regeneration. This was met with a repressive stance by the police, making it clear that the cops will happily execute their masters’ orders to oppress, beat and arrest brutally. Their goals, to build Attiko metro—adding a station where a square once was and “develop” the hill. Using Prodea, the biggest private real estate investment company in Greece and Unison facility services, the government seeks to deliver a safe private yard for their customers and the real estate vultures to take the profiting feast to the next level. All this happens with the total exclusion of the locals and residents from any decisions and planning regarding the neighborhood they live and function in everyday.

The resistance through residence assemblies, initiatives against the metro or Strefi privatization and the hundreds who act and keep the square’s character alive all these years are the only breaks that could delay or even cancel the procedure. Therefore it is urgent that this resistance message breaks the walls of the monopoly of state control over the media and spreads massively into society. A message that echoes hope against the future they have planned for us, a future painted black with the brushes of exception, asphyxiating control and a survival mode imposed with unbearable living costs.

More on Lofos Strefi – Large Treefilled Community Hilltop Threatened

It is important to raise awareness beyond the borders. Exarcheia has symbolic importance in the global movement, but also this can create dynamics in groups and individuals. People can add to and broaden the struggle with priceless experience from similar fights in their realities, and, importantly, interconnect and interact with each other.

Since the visionary sociologist and philosopher Henri Lefebvre’s 1968 book The Right to the City, and the white plans of the Provos, housing, city planning and ecological urbanism have been among other pivotal starting points or distinctive moments in the request for freedom and the pursuit of a meaningful everyday life.

The arsenal of resistance is full, but it has to be used directly with unity, imagination and persistence. Activists with the Exarcheia assembly go by the motto: “If we don’t resist in our neighborhoods, our cities will become modern prisoners. Stop Gentrification. Free Exarcheia!”

Cover image of art in Athens, Greece taken by Niko Georgiades, Unicorn Riot.

For more media from Greece, see our Greece archive page.

UPDATE: Altering Exarcheia From the Square to Strefi Hill: A Timeline and Film

Additional documents (PDFs):

What’s Race Got to Do With it? Looking for the Racial Dimensions of Gentrifícation – The Western Journal of Black Studies (2008)

“Listening Through White Ears”: Cross-Racial Dialogues as a Strategy to Address the Racial Effects of Gentrification – Journal of Urban Affairs (2011)

The geography of gentrification: Thinking through comparative urbanism – Progress in Human Geography (2012)

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: