‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ – Iran is Undergoing a Revolutionary Process

A specter is haunting Iran – the specter of revolution. The Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) is experiencing the largest, most radical and most intense opposition movement in its 43-year history. Its motto is “Woman, Life, Freedom,” coined from the Kurdish movement. At least 500 people have been killed in nationwide protests since last year, about 20,000 arrested and at least four of them have been executed – numerous others could still follow according to the IRI’s jurisdiction. This movement, which has now been in existence for just under five months, has made its revolutionary claim crystal clear since day one: the mullahs and their Islamic Republic must go. There will be no compromise: either the revolutionaries win or they pay an extremely high price in blood – until they come back.

This article is a commentary piece reflecting research, local perspectives and opinions. The views and opinions expressed don’t necessarily represent those of Unicorn Riot.

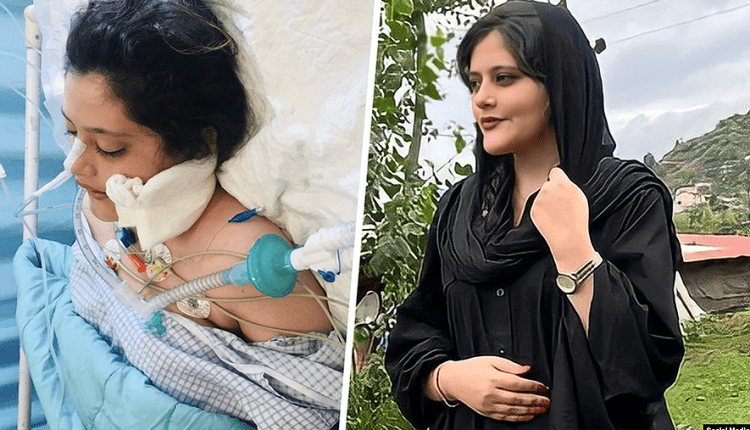

Say Her Name: Jina Mahsa Amini

On Sept. 13, 2022, Jina Mahsa Amini, an Iranian Kurd visiting her family in the capital, was arrested by the Iranian “morality police” in Tehran because her headscarf was not properly in place. The accusation was that there was too much hair showing, that it was “un-Islamic” and “indecent.” Amini was taken to the notorious Evin prison for an “educational measure.” When she was released from there, she was in a coma and died in hospital three days later.

The Iranian authorities took refuge in the typical explanations they have come up with for people killed in torture: Amini had died of an epileptic seizure followed by a heart attack; she had suffered from health problems before. Eyewitnesses have observed otherwise: Amini’s head had been hit on the bonnet of a car during the arrest. Other women in prison at the time said upon their release: “They killed someone there.” Amini’s family also clarified in an interview that their daughter had been in perfect health, and high-ranking Iranian medical experts also publicly stated that there was no evidence of death by heart attack. In fact, Amini’s leaked head CT shows signs of a brain hemorrhage as the cause of death. To this day, isolated members of the IRI establishment regret Amini’s death, but that is the highest of sentiments – never, ever will they admit that they were responsible for her death.

But the people in Iran, who know their regime’s tall tales very well, did not need any leaks or statements by independent medical experts. They knew immediately: a young woman was killed by state officials because of a piece of cloth or “because of a few strands of hair” (Amini’s mother at her funeral). The IRI and its misogynist ideology bears responsibility for this. Full stop.

Immediately after her death was reported, the first rallies and actions took place in the Kurdish part of Iran, especially in Sanandaj – Amini’s place of residence and capital of the Iranian province of Kurdistan – but within a few hours the protests spread nationwide, Amini’s picture and the hashtags #IranRevolution2022 and #MahsaAmini went through the digital world. While experts and reporters all over the world (consciously or unconsciously) are talking down the movement in line with the IRI, talking about “isolated protests” or talking about “reforms,” people are making it clear again and again, in slogans and on house walls: “This is not a protest anymore, this is a revolution.”

By Any Means Necessary

Demonstrations are only one form of action – but one that is already associated with an enormous risk. Any oppositional demonstrations are unregistered, because they are forbidden and their participation is in itself a sin, and thus a criminal offense in the jurisdiction of the clerical dictatorship of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI). “Mohareb” (roughly: “warrior against God”) is the charge, which carries the death penalty. The first such sentences have already been pronounced and carried out in show trials. Mohsen Shekari, Majidreza Rahnavard, Mahdi Karami and Mohammad Hosseini were executed in December 2022 and January 2023, respectively, despite intense international pressure.

Going to such a demonstration therefore means risking one’s life; quite a few demonstrators, especially young ones, therefore say goodbye to their parents and other people they care about every time they leave the house – they do not know if and when they will return home.

A specific form of accepted gathering has been established that occurs for a few days, namely that of the days of death: here, sometimes thousands of people gather at the cemeteries to commemorate killed demonstrators together with their relatives. Either at the funeral or on the fortieth day after the death of a person – according to Islam, mourning lasts 40 days, at the end of which the relatives come together for a ceremony. This form of gathering is tolerated by the clerical dictatorship, and it is claimed by the movement. Not only to come together and sometimes grow into mass demonstrations (where people are shot again, so that the death toll goes on and on), but actually to mourn and process. Often nothing happens until the mothers or fathers of the dead make moving, highly political speeches and call for an uprising.

Most importantly, this practice is directed against the state anonymising the dead. The IRI does not want these dead to become martyrs – they themselves know the power that such a thing can develop, they used it themselves in the revolution against the Shah in 1979. For this, they do not release corpses at all or very late, even kidnap them, carry out secret burials themselves and threaten the families not to go public. The form of collective mourning and demonstrations is directed precisely against this and is therefore so powerful: it gives the deceased names, faces, stories – and sparks anger.

Most often, these demonstrations end in militancy. Clashes with the heavily armed IRI security forces ensue, barricades are set alight and village intersections are blocked, entire municipal government buildings are occupied – often all these things happen together. The militancy of the movement is not only qualitatively more intense than usual, but also unambiguous and unmistakable in its language: it is directed exclusively against symbols of the repression of the IRI, i.e. against the police as well as the hated Bassij militia, their vehicles and barracks, against banks and companies of the Revolutionary Guards, against training centers of the mullahs, but also against all the likenesses of high-ranking government representatives and other propaganda posters. The message is clear: we do not want this Islamic Republic.

Beyond the militancy and demonstrations in the city center, there are two other venues that are shaping this revolution, namely the workplaces on strike and the schools and universities.

The social disruption that has been going on for years (more on this below) has been fuelling strikes and other actions in workplaces for a long time. They bring the class question to the table in a range of sectors, from the oil refineries in the south of the country, to the metalworking and steel industries, to teachers, farmers and truck drivers.

The most significant impact, however, has been the strikes by bazaars and retail workers, who have been on almost continuous strike in certain regions for months. This may not be the most economically significant sector, but it is very formative for Iranian society and is omnipresent in the cityscape; it is simply noticeable in everyday life when entire shopping streets, department stores or politically charged places like the Tehran bazaar are closed.

Universities and schools as venues also characterize the protests beyond the gatherings on the streets. This is where Iranian youth – a large part of the whole society – comes together and makes it clear: for them, this is about the future, which they consider incompatible with the IRI and its old arch-religious and authoritarian seniors.

Both strikes and the protests at schools and universities, shape the content of the movement, here slogans against exploitation, privatization, patriarchy, authoritarianism, capitalism and for equality, solidarity, justice and freedom are developed and carried into the movement. It is therefore no wonder that the IRI attacks these protests particularly harshly and kills or arrests the organizers in an even more targeted manner.

The revolutionary attitude does not pause in everyday life either. Footage circulating from all parts of the country in which women have simply taken off their headscarves in quite unspectacular situations – in a restaurant, while shopping, relaxing in the park. In some cases, one thinks that the headscarf requirement has already been abolished by the people from below. Just a reminder: it is precisely in such situations that the morality police stop and arrest women – as in Amini’s case. Some go even further and burn their headscarves in the open street, for which they usually receive a lot of encouragement. Others knock (expectant) mullahs’ turbans off their heads and “take revenge” in a peaceful and usually also funny way for the massive, encroaching and often violent harassment of those clerics against women (and men) in everyday life. Even at night, in many neighborhoods and blocks of flats, it is: no justice, no peace, no silence. People shout slogans of revolution to each other for hours from their homes. This movement has no happy hours, but is active 24/7.

War Against its Own People

The IRI knows only one language for all major and minor oppositional uprisings and dissent: that of repression, terror and war against its own population. There is no other way to describe what the Iranian state is doing, especially in the border areas inhabited by minorities – as seen currently in Kurdistan in the west and Sistan-Balochistan in the south. The narrative is always the same: the protesters are either direct agents of Western secret services or have lost their way and need to be put on the right track, if necessary by being killed.

The familiar scenario of many observers of uprisings from the outside wishes for some kind of compromise: the demonstrators courageously take their displeasure to the streets, at some point the government has to reach out, allow reforms here and there, the movement would also have to make concessions, there are agreements and everyone lives happily ever after. It is questionable whether this construct will hold up in reality at all. But one thing is certain: it is absolutely useless for Iran.

This regime is neither willing nor able to admit reforms; it only knows its own line, everything else is a threat. On the one hand, this has to do with its character: in such exceptional situations, it becomes particularly clear that the IRI sees its way as absolute and does not understand its citizens as a population, but as subjects – it behaves like an occupier with a zero-tolerance policy. Secondly, the IRI knows from its own experience what concessions can mean. After the Shah made the first concessions in 1978/1979 in the hope of pacifying the revolutionary dynamic, his verdict was in. Now it was: now we will go ahead and only leave when the monarch has abdicated. The mullahs were on the other side of the barricade then and they never wanted to show this weakness. This is not a wild theory or interpretation, they themselves said in the context of the 2019 protests, “If we leave, we leave scorched earth.”

Accordingly, a regime that has built one of the most complex security and repressive apparatuses in the world is cracking down on the movement. From day one, people were beaten, kicked, shot and killed, arrested, kidnapped, abducted and raped (including men) behind the high walls of the numerous prisons and camps, tortured and tried to break souls and wills to live. Not unsuccessfully, considering that some arrestees commit suicide after their time in prison. The very high rate of those arrested shows that this time the regime – presumably due to very high global attention – is not waging the fight against the movement in the open streets and murdering rows and rows of people every day (as in 2019, when up to 1,500 demonstrators were killed in three days), but wants to destroy them physically and mentally in the prisons.

However, the psychological terror does not only take place in the prisons. Again and again, security forces raid entire neighborhoods, put out spotlights and loudspeakers in the middle of the night, from which sweeping statements are made against all fantasies of violence and murder. Afterwards, the troops shoot tear gas into homes and destroy flats, cars, etc. This is not hooliganism, but the rule of law in the Islamic Republic.

Massacres also take place, as in the “Bloody Friday” of Zahedan, the capital of Sistan-Balochistan. Here, almost 100 demonstrators were killed and over 300 injured in one day. The deployment of military troops against those in the Kurdish areas, the heart of the revolution, has also probably cost hundreds of people their lives. We don’t know exactly yet, but some videos of eyewitnesses and residents from cities such as Mahabad, Javanroud and other localities in Kurdish areas show streets with many dead bodies and wounded.

Behind all this is a simple, almost banal strategy: the demonstrators should get scared, be broken, and refrain from their engagement, stay at home, or even leave the country. The IRI is an expert in the business of fear. But when people don’t believe their propaganda and anger trumps fear – then the regime gets a problem. Despite all these terrible practices, people keep coming out, calling new days of action and showing solidarity with each other. The IRI has shown it can hold this line for a long time, but it has been challenged for so long.

Can the movement that has adopted the motto “Woman, Life, Freedom,” familiar from the Kurdish movement, as its program bring down the IRI? And why is this motto far more than just a demonstration slogan, but the program of a revolution of Iran?

WOMAN – Patriarchy and the Women’s Movement

Amini’s death is so unnecessary, so banal, that it brought a long boiling country to the boil and overflowed. Millions of Iranian women know this harassment, and have already experienced it first hand. Amini’s death resulted from a controversial everyday act over a piece of cloth. At the same time, the hijab in Iran is much more than that: it is a key to understanding the ideology of the Islamic Republic and the most important issue of the largest and most significant social movement in the country, the women’s movement.

In the 20th century, the monarchist dynasty of the Pahlavais – Western-oriented, authoritarian modernisers from above – had banned the wearing of the hijab. In the 1979 revolution, which was supported by many different forces in the country, it was reinterpreted as a symbol of resistance against the Shah; many women, including leftist, progressive and feminist ones, donned it for strategic reasons.

After the revolution, the mullahs, led by the IRI’s first head of state Ayatollah Khomeini, secured power through massive use of violence and terror against former allies. By means of bans, imprisonments and mass executions, they destroyed the formerly strong communist parties as well as the People’s Mujahedin and thus secured sole rule for themselves.

Forced veiling was of paramount importance to the Islamists. Their image of women focused on the role of women as supportive companions who had to take care of the reproductive tasks within the family. At the same time, women were held responsible for the moral decay of society and deplored by the new regime. The new rulers saw the solution to this decay in the wearing of the hijab. Khomeini once said: “If the Islamic revolution has no other result than the veiling of women, then that is per se enough for the revolution.“ In other words, the mullahs control society through women.

However, the compulsory headscarf also provoked resistance from the women’s movement, which at least delayed the introduction of the hijab. But even after the establishment of the IRI, women repeatedly scandalized the deeply sexist reality of life in the country. After all, the charged piece of cloth was only the tip of the iceberg. This also included issues beyond the dress code, such as marriage and divorce laws, the right to have a say beyond male caregivers, the minimum age for (forced) marriage and criminal responsibility, the right to abortion, the existing occupational bans, representation in politics, etc. But the hijab symbolically united all these shortcomings of society, especially in everyday life.

See a detailed description of the variety of IRI‘s laws discriminating against women in Majid Mohammadi’s report, “Iranian Women and the Civil Rights Movement in Iran: Feminism Interacted” In: Journal of International Women‘s Studies Vol. 9 #1. S.3.

Today, women have been fighting against the regime for decades with means of civil disobedience. They have been able to enforce that, especially in big cities like Tehran and Isfahan, the headscarf is deliberately worn more and more carelessly and more hair is shown.

A few years ago, campaigns were launched in which women without hijabs and/or in “garish” clothing go out into public spaces and film each other doing so. In Dec. 2017, Vida Modavahed – a single mother from a humble background – climbed an electricity box on Tehran’s iconic Revolution Street, removed her white headscarf and waved it on a pole – the iconic photo went around the world and seems almost prophetic today. For in the current protest movement, too, the removal of the hijab and the strong presence of women in the front row is the sign that characterizes this wave of protest and does lasting damage to the legitimacy of the IRI.

LIFE – Social Powder Keg

The current movement, like the last waves of uprisings in Iran, did not fall from the sky. One cannot understand its intensity and radicalism without the context and situation in which the country finds itself politically and economically.

First, the IRI has a core defect in how its personnel lack the know-how for many issues in the complex world of the 21st century. In the IRI’s politically authoritarian system, the few truly influential positions are occupied exclusively by religious scholars who have undergone a strictly clerical education.

Secondly, the IRI is highly corrupt. A conglomerate of mullahs and the industrial-military-economic complex of the Revolutionary Guards divide all key sectors of the economy into so-called bonyads, i.e. that award each other contracts, permits and decisions with the aim of maximizing their own profits.

The gigantic social gap between the members of the state apparatus and the population is becoming ever more apparent as a result of the sanctions: while the rulers do not budge one iota from their luxurious lives, more and more people are plunging into existential crises and do not know whether they will still be able to feed themselves and their families the next day.

Inflation for 2022 was close to 40%, and it is estimated that 40%-50% of Iranians live below the poverty line of $200 a month. This state of affairs is exacerbated by the IRI courting sympathy and proclaiming that all budgets in the country must be cut, while at the same time billions continue to flow to proxies in the region to continue the proxy war against the West – in Syria, Israel/Palestine, Yemen, Iraq and elsewhere.

The reality of recent years also includes the fact that the people of Iran are so desperate, the country is becoming a powder keg. Various occasions become the famous drops that bring the barrel to overflowing; it can be unaffordable food or petrol prices, ecological crises or, as happened now, the death of a young woman because of the hijab. Since 2018, the lower classes and poorer people are regularly on the streets; once they were seen as the social base for the Mullahs, but this base has turned into a dangerous oppisition. It was these people who were responsible for a radicalization of the

protests. The slogan “Reformers, conservatives – the game is over” manifests that trust in the political system has been shaken and the population has lost all faith in the pseudo-democratic procedures.“

The people’s response has been continuous strikes and other actions in the workplace. In Iran, over the last few years, hardly a day has gone by without such strikes, which are admittedly mostly small. It should be noted that the official trade unions in Iran are an extension of the state and thus a sham institution. Any independent trade union organization is forbidden and is also severely punished.

After almost every action, sometimes hundreds of workers are arrested, which damages any organizational momentum. And yet the workers refuse to be intimidated. In particular, the independent teachers’ union Iranian Teachers’ Trade Association (ITTA) has established itself as a kind of unifying spearhead of a new workers’ movement. It is well networked, receives a lot of support from all sectors and has organizing strength: in 2021 it organized a strike wave in which there were actions in over 300 places nationwide. Thanks to them and the entire Iranian workers’ movement, a large number of strikes are currently a central element of the movement and make it clear that it is also to a large extent about class struggle.

1) #IranRevolution: A week ago, many contract workers in the oil and gas industry went on strike in many regions and cities. So far mostly temporary workers in this sector have been on strike. How should the strikes be assessed?

— DunyaCollective (@DunyaCollective) January 24, 2023

A thread with Hamid Mohsen (@balaclav04) pic.twitter.com/1DbHuvP6YB

FREEDOM – The Kids are Alright

Two elementary aspects of the IRI’s rule are thus currently their undoing and are fueling the protests: the oppression of women and the massive social disruption of the last decades, especially against the numerous minorities in the multi-ethnic state. This leads to the composition of the movement, which this time can justifiably claim to be one that represents the whole of Iranian society: Women, men, all ethnic and religious minorities and virtually all classes. But also and above all: the youth.

Iran is an extremely young country, the average age is 31.7. By comparison, the average age in the USA is 38.7 (middle of the pack), in Germany even 47.8 (second oldest in the world). So, almost by necessity, the youth is always part of movements – this shows the traditionally important role of universities as venues or multipliers of protest movements over the last four decades.

What stands out this time, however, is the Iranian Generation Z: minors and teenagers are an important motor of the movement, especially at girls’ schools (in Iran, the school system is gender-segregated, partly still including up to university). There have been, and still are, impressive scenes of young women and girls literally chasing away school staff loyal to the regime or representatives of the Ministry of Education with shouts of “bisharaf” (which means “honorless,” an insult claimed by the youth from their religious authorities).

However, many of the demonstrators who were killed are also exactly this age. The fact is that the Iranian Gen Z is developing and radicalizing itself as a political subject, and no matter what the outcome of this wave of the revolutionary process, the break with the system is irreconcilable for them.

This is no wonder, after all, this generation, like all people in Iran, is at home in the digital age. Public spheres such as politics, culture and education in Iran are constricted by clerical authority and are inaccessible to many, so they flee into the digital sphere. This flight can be traced like a red thread through the history of the IRI: In the late 1990s-early 2000s, when a brief reformist episode allowed the country some breathing space, many progressive and critical blogs and websites emerged; the green movement was one of the first major ones in the world to organize and express itself through social media; during the Coronavirus pandemic and the period of digital education, many families felt compelled to get their children smartphones.

Iranian society, especially the youth, is at home in the digital age and is informed: they are well aware – in the pre-digital era through contact with their families in exile – of the lifestyle, cultural preferences, political-philosophical debates and much more in the West. The social question is imperatively global in the age of digitalism – Iran is a prime example. And this creates a massive clash in lifestyle, habitus, character and soul between the young Iranian population and the aging mullahs: here a cosmopolitan, life-affirming and informed youth, there a clerical dictatorship with Sharia laws from the Middle Ages as well as death and ancestor worship. This clash is currently more noticeable than ever.

Brave Iranian youth write “Death to Khamenei” all over the city.

— Sara Bahari (@Bahari_Sara) February 16, 2023

Shiraz, #Iran

Thursday, February 16,#IranRevolution #مرگ_بر_ستمگر_چه_شاه_باشه_چه_رهبر pic.twitter.com/F0PGLiyOR0

Prospects – Where are we Heading?

It is currently completely open in which direction the charged situation in the country will develop. It is quite conceivable that this movement will bring the IRI to its knees. For the time being, the IRI has survived the first, long-lasting and intensive wave, however, among other things also due to the onset of winter- But this is still far from a long-term victory over this movement. It has often looked as if fear would set in and people would stay at home, but each time it has resumed. One thing is certain: in the medium and long term, the youth affected by social and political misery will no longer tolerate the old men, patriarchs and dictators of the IRI.

Solidarity has been shown across the globe, which is very important for the revolution to keep up the attention. Germany and Berlin – with a traditionally big Iranian diaspora – have seen many solidarity actions and demonstrations. On Oct. 22, 2022, around 100,000 people showed solidarity with the revolutionary movement in Iran on a day of historic mass demonstrations, the biggest ever in Iranian diaspora.

Furthermore, there are permanent picket lines in front of the headquarters of the German green party (part of the government and in responsibility for ministry for foreign affairs) as well as in front of the Iranian embassy. On Jan. 16, 2023, 35,000 people gathered in Strasbourg (France) to demand the listing of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard as a terrorist entity by the EU.

Several demonstrations take place, also with the as well very vibrant Kurdish community. The attacks against Kurds carried out by Turkey and Iran are answered with the chant: “Erdogan and Khamenei – fascists“ and “Kurdistan, graveyard for fascists.”

The people in Iran see these actions in Berlin and elsewhere and are empowered by them. Not only they see it – the Islamic Republic is held back by even more intense repression by the global attention. Its secret service and their supporters have a tradition of insulting, harassing and killing opposition leaders beyond their borders. Numerous attacks have been reported on organizers of solidarity events in the UK, the US and also in Berlin, including an assault with a knife. This shows that the vast support in the diaspora has an effect.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: