African Coups Boot French Colonizers, Leave Power Vacuums

On July 26, 2023, the presidential guard detained Nigerien President Mohamed Bazoum and placed him under house arrest. The perpetrators then appeared on national television and announced to the nation they were seizing power to end Niger’s deteriorating security situation and bad governance. Days later, head of Guard General Abdourahamane Tchiani was declared head of state. This is only one of the eight coups in Africa since 2020, six of which were in former French colonies. Niger, Mali, Chad, Guinea, Gabon, and Burkina Faso have all come under the control of a military leader in what some are dubbing the ‘Francophone Spring’ as countries seek further independence from French control.

Although no coup is identical, military regimes now control a contiguous bloc of African nations that stretch from the Red Sea in the east to the Atlantic Ocean in the west. The French military withdrawal from states like Niger has created a vacuum that other foreign influences like Russia’s Wagner Group, among others, have been prepared to fill.

This is an analysis on the coup in Niger, among others, the collapse of French influence in Africa, and the wider implications for these massive shifts in the region.

A Military Coup in Niger

A day after Bazoum’s house arrest, the army threw its support behind the emerging junta to “avoid a deadly confrontation between the various forces” The new head of state, General Abdourahamane Tchiani, promptly suspended Niger’s constitution.

The justifications for this have overlapped with other similar coups in the region. The junta cites security failures and economic mismanagement. The security situation in the area is extremely alarming, as can be seen by the fact that 43% of global deaths due to terrorism occurred in the Sahel region in 2022. However, this has already been a consistent problem for the past decade, and the economic “justification” is hard to reinforce.

Niger’s economy before the coup was projected to grow by an impressive 6.9% in 2023 and even further by 12.5% in 2024. The overthrow was, in fact, likely opportunistic, pragmatic, and self-preserving. Bazoum had planned to install new military leaders, and General Tchiani’s position as head of the presidential guard was under considerable threat. These plans, coupled with the wave of hostility towards civilian-led governments across Niger and all of Africa, made General Tchiani’s decision seemingly straightforward.

Not long after the overthrow, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) sent an ultimatum to Tchiani and his junta. Members would suspend their air and land borders with the newly led state, along with any diplomatic relations, if Bazoum was not returned to power. The European Union (EU) backed ECOWAS in its demand. On August 20, Tchiani appeared on national television to reiterate his plans for the country and add that Niger would defend itself if foreign influences attempted any sort of military intervention.

Very quickly, the bordering military-led states of Burkina Faso and Mali issued a joint statement warning ECOWAS that any intervention in Niger would be “tantamount to a declaration of war against Burkina Faso and Mali.” These two nations resting on Niger’s western border have also both undergone military coups within the past three years. On September 15, all three signed a mutual defense pact against jihadism and any ‘external aggression.’

The coup has taken a toll on the nation. ECOWAS sanctions have affected Niger’s food supplies, leading to an increased cost of basic goods. It is also documented that international organizations, especially in rural areas, provide services to roughly 700,000 internally displaced people. The presence of these organizations is under threat.

On top of this, the EU has frozen over €500 million in security aid. Local pharmacies are running out of stock, and hospitals are struggling to provide the necessary vaccines for infants. According to the United Nations, Niger is ranked last on the Human Development Index, and this struggle will only be exacerbated under such circumstances.

Despite winning 56% of the vote in February 2021, President Bazoum’s ousting has been widely celebrated in Niger. This is largely because of his closeness with French President Emmanuel Macron and Western influences in general.

Françafrique

No coup in Africa is identical to another. But the civilian government giving way to a military junta in Niger as well as the people’s vitriolic anti-French sentiments do overlap considerably with those of other Francophone nations.

One of the justifications for the removal of Bazoum is that he is simply a puppet for French interests. The displacement of such an alleged ally of Macron led to popular protests and even hostility towards the French embassy in Niamey. This resentment towards the country’s former overlords has been brewing for years.

One of the issues many African nations have with the French presence is the unfair extraction of valuable natural resources. For example, in Niger, there has been condemnation of the French company Orano for exploiting Niger’s uranium supplies by using political influence to secure favorable contracts.

Despite producing 5% of the world’s uranium and being the EU’s second-largest supplier of uranium in 2022, exports have failed to boost Niger’s economy. Further feeding into popular unrest is the fact that 100,000 people could have their health threatened by the dangerous radioactive gas, radon, which is exhausted from the mines.

In 1994, the founder of the non-governmental organization Survie, François-Xavier Verschave, defined the term Françafrique as “the secret criminality in the upper echelons of French politics and economy, where a kind of underground republic is hidden from view.”

Seven of the nine Francophone states in West Africa still use the CFA (African Financial Community) franc, which requires its members to deposit half their foreign exchange reserves in the French treasury. This imposition is transparently fraught with elements of the stubborn historical Françafrique, despite the illusion of tidy modern diplomatic relations.

A case such as Vincent Bolloré’s in 2018, where the billionaire was charged with corrupt contractual ties with the leaders of Guinea and Togo, only brings to light an ongoing and poorly disguised imbalance. The French military has also regularly intervened on behalf of pro-French leaders in African nations.

Influence in Africa gives France renown and “plays a key role in justifying France’s permanent seat on the UN Security Council,” argues Professor Tony Chafer of the University of Portsmouth. The justification for such a heavy presence for the past decade, as the French defense ministry claims, has been the mission to combat Islamic militant groups, particularly in the heavily affected Sahel region. The beginning of this was Operation Serval in Mali, shortly after jihadists took over the north of the country. This was replaced a decade later, in 2022, by Operation Barkhane, which concluded in November. Both operations have, simply put, failed.

Today, the French military presence appears redundant, as the security situation has only deteriorated. The people see this foreign intervention as plainly ineffective and unnecessary.

As the popular French newspaper Le Monde wrote, “French influence in the Sahel has collapsed.”

The Francophone Spring

The overthrow of French-aligned civilian governments has been perceived by many as a form of modern decolonization. The generational exploitation of such domineering relationships dates all the way back to the slave trade, and activists such as Beninese writer Kémi Séba applaud the breakaway.

Emerging juntas and their adoption of an explicitly anti-French outlook are currently a populist policy for the new regimes and a way to disassociate from the previous government they label ineffectual.

As Mutaru Mumuni Muqthar, executive director of the West Africa Centre for Counter-Extremism, says, “There is a strong anti-French sentiment due to the exploitation on the part of France.” There have been numerous displays of such feelings in former French colonies.

In Gabon, after military officers deposed President Ali Bongo, many ordinary people took to the streets in elation. Ali Bongo’s plea for intervention from international communities was swiftly turned into a meme and mocked by Gabonese citizens on social media.

In Guinea and Niger, overt displays of anti-French sentiments were broadcast to the world. In Mali, Colonel Abdoulaye Maiga delivered the message personally by launching an attack on the French leadership in September 2022, claiming they had stabbed Mali “in the back.”

Like his predecessors, Macron claims that the neo-colonial Françafrique has been long dead and, although only fractionally fulfilled, as a show of such faith, he pledged to ship back artifacts to nations such as Kenya, South Africa, Angola, and Ethiopia.

In February, Macron also promised to reduce military presences and create a different nature to any such relationships with a more cooperative outlook on operations.

Francophone nations in Africa have truly sprung, and French influence has waned. However, although 78% of the 27 coups since 1990 in sub-Saharan Africa have occurred in former French colonies, it must be noted that this is not a movement on the continent exclusive to these select states.

Beyond France

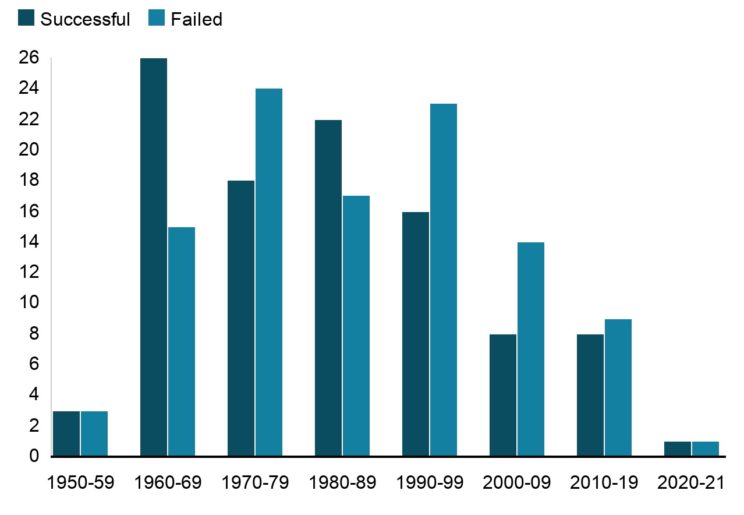

According to American researchers Jonathan M. Powell and Clayton L. Thyne, of the 486 attempted or successful military coups to occur across the world since 1950, a staggering 214 were in Africa. 106 of these were successful, and studies suggest this change is generally perceived domestically as positive.

Weak democratic processes and deepening economic inequality have contributed to what Afrobarometer CEO Joseph Asunka notes as a democratic deficit. Increasingly uncertain security, especially in the Sahel, means many believe the iron fist of military leadership is required to combat such activity.

Across 36 African nations polled in 2021-22, only 38% of citizens believed the democracy of a civilian government was delivering what was required of them. Such dissatisfaction has manifested increasingly in younger generations.

As well as this, according to Afrobarometer, 56% of Africans aged 18-35 tolerate military intervention if their democratically elected representatives are deemed to be abusing their power. This is higher than the over-55 representatives, of whom only 48% agreed.

Because of the continent’s widespread military coup attempts, it is hard to label the issue an exclusively Francophone one. Since 1952, former British colonies have experienced countless coup attempts, and to highlight just a few examples, Sudan has had 17, Sierra Leone 10, Ghana 10, and Nigeria has had eight. This is despite a somewhat more laissez-faire approach from Britain towards their former colonies compared to the French.

Despite the increasing support for military government, findings from 28 African nations in 2022 found that 43% of adults still believe the military should never intervene in politics. This lack of comprehensive support, coupled with the French withdrawal, means newly installed regimes require supplementary backing to stabilize their rule, not only from neighboring militarily led states but also from larger foreign forces.

Some have identified what they dub as a new “scramble” for Africa with recent developments. Turkey, China, India, and the United Arab Emirates all appear to have a vested interest in the continent, but the most prolific foreign influence is Russia and its private military company, The Wagner Group.

The Wagner Group in Africa

Since the 2010s, the Wagner Group has been influencing countries across the continent. Particularly in states that help them disrupt the Western bloc. Wagner not only provided its highly valued military security and training to newfound African governments but also developed mining and energy deals to exploit natural resources just as the previous French regime did.

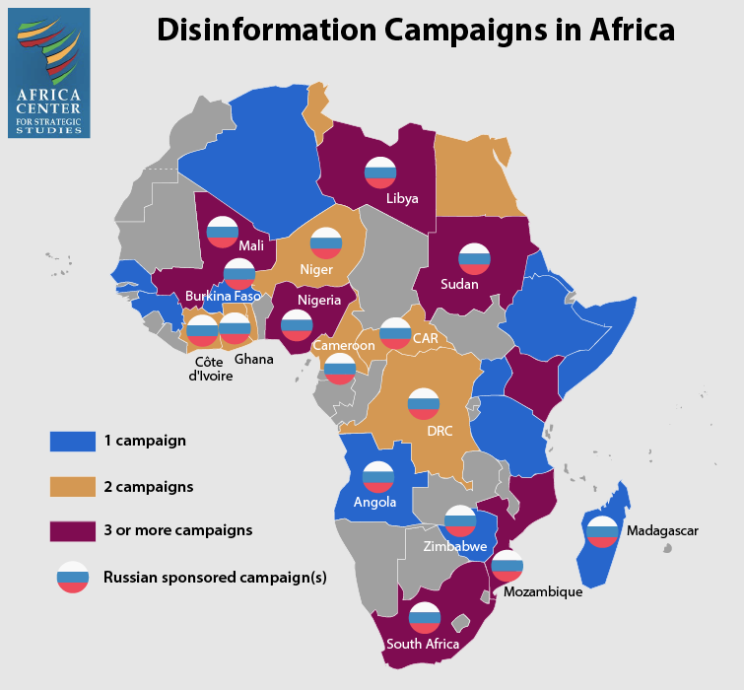

In September 2021, Mali’s military leadership signed a security deal with Wagner to deploy 1,000 personnel. The junta agreed to a monthly cost of $10.8 million, and since the deal was signed, Wagner’s mounting activity has also managed to reach states such as Mozambique, Madagascar, the Central African Republic (CAR), Sudan, and Libya.

African expert Sergey Eledinov said of Moscow’s rationale for using Wagner Group in Africa, “Russia doesn’t know how to do business in Africa. Wagner does.” This highlights the autonomy the group is permitted to exercise when seeking profit in their African endeavors. Another benefit for the Russian leadership is the disassociation that can be employed when, for example, the group is accused of human rights abuses in central Mali.

Russian influence has filled the vacuum left behind by France. It has been a replacement, celebrated by many. In Niger, Russian flags were waved by supporters of the coup. On July 30, one sign amongst a jubilant crowd in Niamey said, “Down with France, long live Putin.”

The positive sentiment has potentially been fostered by Russian disinformation campaigns throughout Africa dating back at least to 2014, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. Many of these campaigns target social media platforms such as TikTok, Twitter, Telegram, and Facebook to sow distrust in rival actors in the region, such as France and the UN. Since 2021 alone, there have been reported trolling and disinformation campaigns to undermine the West, undermine democracy, and promote Russian interests in Mali, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Sudan.

Russian activity in Africa is generally frowned upon outside of the Kremlin. In June, Macron claimed Russia is “Destabilizing Africa,” and Nigerian President Bola Tinubu, along with other West African nations, has drawn up plans to create an “anti-coup” force, an explicit rejection of newly installed juntas and their associations with The Wagner Group’s mercenaries.

The politics in the region and Wagner’s activity remain complicated. U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken publicly denied any possibility of Russian involvement in the Niger coup, despite Wagner’s former leader Yevgeny Prigozhin’s presence in Niamey only a day after the coup.

It is also germane to the discussion to acknowledge the hypocrisy of the Western bloc’s disapproval. Just one recent example is the fact that France and the U.S. backed the military coup in Chad in 2021, yet today condemn the Wagner Group for assisting militarily led governments. As well as this, there are some reports that Wagner Group’s interference is being exaggerated in some cases. For example, in December 2022, Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo alleged that Burkina Faso had hired Wagner mercenaries, despite these reports being unconfirmed.

There is no doubt that the Wagner Group is the embodiment of Russia on the continent. In August, Prigozhin declared from the ground in Mali, not long after the short-lived mutinous march to Moscow, that their goal is “making Russia even greater on every continent – and Africa even more free… justice and happiness for the African nations.” With the military chief’s death and the ever-more numerous and convoluted power struggles in the likes of Burkina Faso, Niger, Sudan, Mali, and the CAR, the Wagner Group’s ongoing role in Africa remains increasingly important and equally complex.

In Summary

The wave of military coups across Africa has been labeled by some as a modern wave of decolonization; however, it is hard to believe in true liberation when other foreign actors, such as Russia’s Wagner Group, are so quickly filling any vacuum left behind by the French.

Democracy has failed in the region because of exploitative practices and corruption. Many of these states are the poorest in the world, and the security situation, particularly in the Sahel, is only getting worse.

It is doubtful that new military regimes will truly benefit the people any more than the civilian governments did, despite some jubilation in the streets. This is a period of explicit uncertainty on the continent, and particularly in the Francophone states.

Cover image with soldiers of the Republic of Niger in 2015 via Creative Commons.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.