Greece Marks 50th Anniversary of Polytechnic University Uprising Against Military Dictatorship

The background of a popular revolt that was the start of the end for the Greek military junta

Athens, Greece — Over 50 years ago in 1973, a U.S.-backed military dictatorship controlling Greece killed dozens of people during a popular uprising against the far-right junta. Every year since then, remembrance of November 17 has been ingrained into the country’s anti-authoritarian fabric.

For the 50th year, Unicorn Riot heard from participants of the uprising, including a man tortured by the military, see our mini-documentary and report below.

When you are a schoolkid in Greece you are taught two important dates that are national holidays. One of them is Greece’s Independence Day, March 25, marking the date in 1821 when the Greek revolution started against the Ottoman Empire. The other one on October 28 is known as “Oxi Day,” to celebrate when Greece said “Oxi” (No) in 1940 to Italian fascist Benito Mussolini, who wanted Greece to surrender before Italy invaded.

Then there is November 17, a holiday in all levels of the Greek educational system. The day has been commemorated since 1973 when the military slaughtered students uprising against the military dictatorship, also called junta, that oppressed Greece from 1967-1974. “It was a heroic revolt of the students who were saying ‘down with the junta,’ and ‘bread, education, freedom,’” said Vaggelis Gkiougkis from the Association of Imprisoned and Exiled Resistance Members.

Every year there are demonstrations held by students of universities and schools in Athens and many cities and islands.

Massive demonstrations across #Greece marked the 50th anniversary since November 17, 1973, when the military junta killed dozens of students during the Polytechnic Uprising.

— UNICORN RIOT (@UR_Ninja) November 18, 2023

Thousands paid respect to the fallen at Polytechnic & upwards of 50,000 people marched in Athens today. pic.twitter.com/hRgo74Vzew

The “Regime of the Colonels” dictatorship started on April 21, 1967 with a coup d’état by right-wing Greek military officers who feared the election of a leftist government. This phase of Greek history can be seen as a continuation of the Greek Civil War in 1946-49 between Communists and right-wing monarchist forces which occurred after the fierce left-wing Greek resistance to German occupation during World War II.

Much like the fighting against leftist and Communists forces in the ‘40s, the Greek dictatorship was made possible by the support of the West. The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had a big interest in keeping Communist influence away from Greece and preventing leftists from winning elections.

Coup leader Giorgos Papadopoulos and his regime immediately established an atmosphere of fear with thousands of arrests. Many leftists and activists well known to the authorities were rounded up and transported to prisons and islands in the Aegean Sea like Gyaros, where they endured torture and hard climatic conditions and the denial of basic human needs.

Two elders who were exiled to the Greek island of Gyaros have spoken to Unicorn Riot over the past two years. Theodoros Tellidis was 89 years old in 2022 when he shared his story while at the Nov. 17 gathering in Thessaloniki. He said he was abducted by undercover police officers and sent to solitary confinement and then sent to Gyaros on a tanker after he refused to speak with them.

Also sent to Gyaros was Vaggelis Gkiougkis, who shared with us that in ‘67 after the dictatorship was taking over, he went to warn some of his friends and ended up being caught by the military and sent to the island.

Gkiougkis spoke of the forms of resistance to the junta and the torture doled out against those caught while giving a tour of the Greek military police’s special interrogation building. As he showed images of the island, he recalled the humidity and “the inability to sit in one place without having eaten dust.”

The dictatorship collapsed on July 23, 1974, after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus.

For more on the military dictatorship and Nov. 17 protests, see our 2022 report: Greek Students Riot on November 17, Commemorate Those Killed by the Junta

The Uprising, Its Reasons and Its Anti-Authoritarian Vision

For years, organizing against the dictatorship was a risky business. Everything had to happen discreetly and without many experienced people who were already in prison. The actions of the ongoing struggle were limited to secret distribution of flyers and newspapers, fast banner actions at central buildings and small-scale sabotage.

Public gatherings and demonstrations were practically non-existent. Occasionally funerals, like that of the well-known national poet Giorgos Seferis or the politician Giorgios Papandreou, were used by the masses to express discontent with the regime.

The student movement, which already started before the Polytechnic Uprising, was a welcomed chance to test the waters for more offensive and public actions. Before the student movement started it was very fragmented, consisting only of peer groups with different interests.

The authoritarian and traditional values of the military dictatorship produced an atmosphere of fear and thus had its negative effects on socialization and the articulation of collective political thought. But as long as the dictatorship seemed to hold, the more the students and university became the only possibility where public anger could be expressed. This was possible because students had the privilege to develop in the shadow of the university a counter-culture and address questions of democracy by meeting like-minded people. At the same time this privilege was only reserved for students and did not directly represent workers and thus questions of class.

The latter were part of the thoughts of the students — as the important slogan “Bread, education, freedom” declares — but not part of their reality. Similar processes happened also during student uprisings in Western democracies.

The spark of the protests was the demand for free and fair elections for the student unions and the interruption of deferred conscription on account of studies in attempts to hinder student syndicalism by decapitating the movement from its leadership. But from the beginning, the students aimed toward the bigger picture — the dictatorship itself.

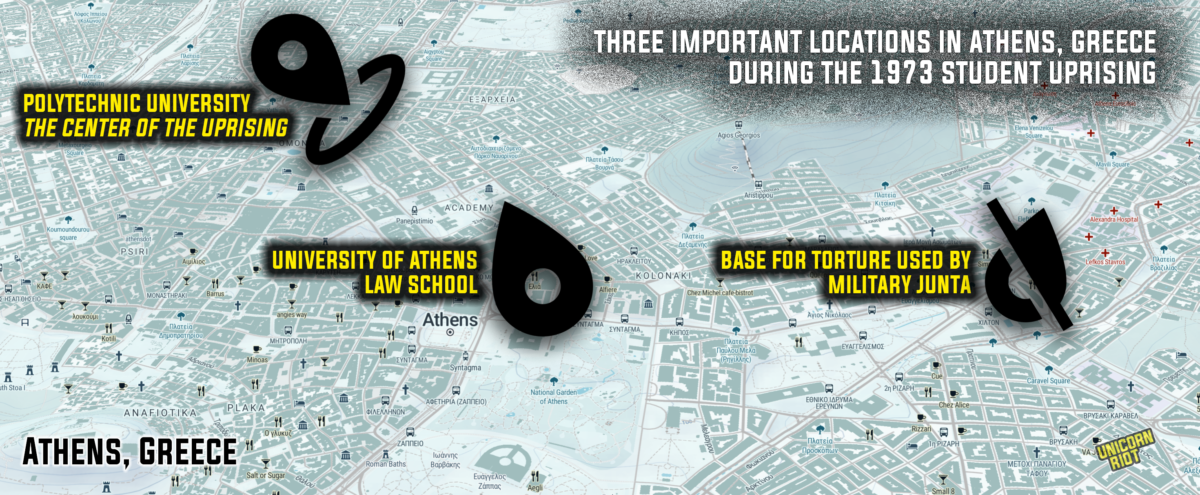

Starting in 1972, the student movement in Athens developed a dynamic of spontaneous demos and actions that culminated in the occupations of the law school at the University of Athens in February 1973 and the November 1973 occupation of the Polytechnic University (National Technical University of Athens).

Further important reasons for the birth of the student movement were:

- The complete failure of the regime to attract the young people. Nationalism, puritanism and authority were not appealing.

- Lack of economic perspectives in a future with a military regime.

- The necessity for spaces to produce counter-culture.

- Recent familial memories about resistance to the German occupation and the civil war in Greece, which formed a progressive contagiousness in the minds of the youth.

- The influence of the international ‘68 movement, resistance to the Vietnam War and the student movements bubbling up all over the world.

“The inner life of the anti-dictatorial student movement had elements that everyday life did not have. Collectivity, mutual respect, solidarity, comradeship, emotional commitment, dialogue and freedom of speech put you in another human sphere, where the individual yields to the collective,” said Olympios Dafermos, a participant of the Polytechnic Uprising, in his book.

“The moments of rebellion (the movement lasted 22 months) are intense and joyful. You feel you are shaping the social reality in which you live. In a way you create the world and you live it intensely. You are self-determining and at the same time you are going along with your colleagues. The community is also your affair. You belong to it. Within it you evolve, you collaborate, you give and take, you act, you dream and you are happy…”

1973: A Brief Timeline of the Greek Student Movement and the Polytechnic Uprising

February 12: The regime announces the law for the interruption of deferred conscription on account of studies.

February 13: Student demonstrations in Athens and Thessaloniki (second largest city in Greece)

February 14: Protests of around 1.000 students at Polytechnic in Athens. Brutal invasion of civil police and arrest of 11 students.

February 16: 3,000 students occupy the law school demanding the repeal of all anti-student ordinances, the interruption of deferred conscription on account of studies and the release of the detained students of February 14. The occupation lasts one day and ends with a demonstration that was attacked by police.

February 19: Pan-student gathering at the Polytechnic University. In almost all faculties students practice abstention from the courses.

February 21-22: Another occupation of the law school of Athens by 4,000 students. The building is encircled by police and students loyal to the dictatorship. Students end the occupation and start a demonstration with 30,000 people that was attacked by police.

March 20: Attempt to re-occupy the law school ends with 100 arrests.

November 4: Demonstration-turned-riot during the memorial for the politician Giorgos Papandreou. Over a dozen arrests were made.

November 13: Twelve of the 17 arrested during the November 4 demonstration were declared innocent by the court and the other five were released with suspended sentences.

November 14: Gatherings because of court decisions. In the morning, general assemblies took place in different universities across Athens to discuss the matter of student elections. Around noon, the information came out through word of mouth that scuffles broke out between students and police at Polytechnic University. More than 1,500 students marched from the law school, where a big assembly was taking place, to the Polytechnic, a kilometer away, and joined the protests there. The complete occupation of the Polytechnic was announced at 9 p.m. Around midnight the gates were closed and guarded by self-organized security groups. Preparations started for an illegal radio station.

November 15: After an extraordinary meeting, at 8 a.m. the senate of the Polytechnic decided to send a request to the regime to not intervene in the Polytechnic. The gates of the building opened at 9 a.m. and the declaration of the students Coordination Committee was distributed. Students arrived from other cities to reinforce the occupation. Operation of the radio station started from which the ‘voice of the Polytechnic’ calling for a “general uprising” and “general strike” was heard all over Greece. The University of Ioannina was occupied. Around 5 p.m., a police kettle around the Polytechnic was broken once more and many students and youth joined the occupation. Food, drinks, cigarettes and medicine were collected throughout the day. The information spread fast through word of mouth, the radio station and even the declarations posterized on buses. Workers and farmers also joined in the mobilization and quickly the occupation became a matter of the whole society.

November 16:

11 a.m. The senate of the Polytechnic repeats its decision and request to the regime that the university asylum should be respected and the forces of law should not intervene.

3:30 p.m. Press conference was held by the students.

6:00 p.m. Around 30,000 people gathered around the Polytechnic.

6:30-7:00 p.m. A spontaneous demonstration of 2,000 took place in the city center. The pirate radio station of Polytechnic declared: “We denounce two deaths from gunshots in Klathmonos Square… All here, in the struggle against the junta. Greek people, we need you! All united! Down with the Junta!”

8:00-9:00 p.m. Teargas was deployed by police around Omonoia Square and in the city center.

9:00 p.m. Demonstrators erect barricades in the streets around the Polytechnic by using buses, cars and other objects. Confrontations continued to gain tension.

9:30 p.m. Police announce curfew in the city center.

10:00 p.m. Armored vehicles appear in the streets around the Polytechnic and launch tear gas.

11:00-12 p.m. The center of Athens resembled an urban battlefield.

November 17:

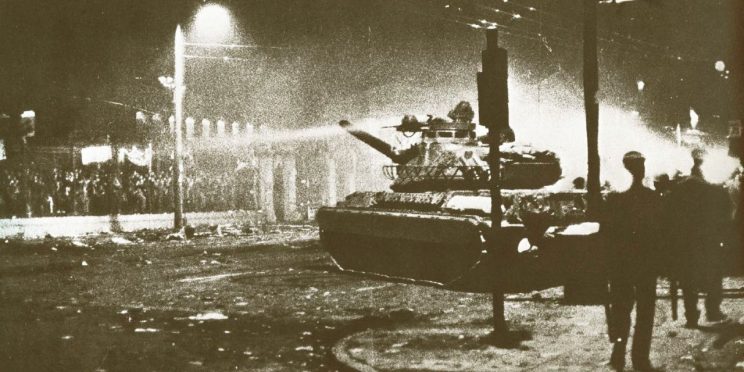

12:15 a.m. The first military soldiers and tanks appear in Ampelokipoi, a district close to Polytechnic.

1:00 a.m. Tanks appear at Patission Street close to the Polytechnic. Some demonstrators start to retreat and shelter in surrounding residential buildings. Snipers got positioned in buildings around the Polytechnic. Confrontations continue at the barricades.

2:00-3:00 a.m. Soldiers, tanks and police set up in positions in front of the Polytechnic. Negotiations take place.

2:30 a.m. Stationed with the commander of the special military forces and armored vehicles at the Acropole Palace hotel, the head of the police forces called for the students to leave the Polytechnic in half an hour.

2:59 a.m. Three tanks move toward Polytechnic. One of them crushes the gate and many people who were standing behind it. Confrontations continue in the Polytechnic from building to building.

3:35 a.m. According to eyewitnesses, the Polytechnic was emptied and ambulances were taking injured and dead people. Shootings and confrontations continue around Polytechnic.

6:00 a.m. The occupation of the Polytechnic in Thessaloniki, which started in the afternoon of November 16, was also evicted. It was encircled by tanks and many arrests and beatings occurred.

11:00 a.m. Military law was established. Demonstrations and confrontations continue until the night.

The exact number of the victims differ and many questions remain unanswered. According to Gkiougkis “the death toll of the uprising must be around 26.” But there are also several unidentified bodies and even many deaths that occurred later because of injuries and illnesses related to the events. “So basically there are more than 70 people who died because of the Polytechnic” emphasized Gkiougkis.

The court case against the initiators of the bloody attack on the occupation of the Polytechnic started on October 16, 1975 and ended on December 30, 1975. 20 of the accused were sentenced from prison terms to life imprisonment. 12 were acquitted.

The Uprising is Not Over

This year, the demonstrations and events around the 50th anniversary of the uprising were bigger than the years before. According to the student unions, there were 50,000 participants, according to the police, 25,000.

A central topic of this year’s demo was solidarity with Palestine — parts of the march continued to the Israeli embassy after reaching the traditional ending point at the American embassy.

One central slogan heard from different blocs of old resistance fighters to student unions and left-wing organizations was: “The Polytechnic was not just a feast, it was an uprising and a people’s struggle.”

For many of them, the struggle against fascism and authority is far from being over, especially under the current right-wing government of Kyriakos Mitsotakis and his party Nea Dimokratia. Mitsotakis won the last elections in June by a big margin: 41% against 17% of the left-wing party Syriza and govern alone without a coalition partner. Mitsotakis and ND have survived numerous high-profile spy scandals, the Pylos shipwreck which was the deadliest migrant shipwreck in modern history, a train crash that killed 57 people and claims of horribly handling ecological catastrophes like fires and floods.

Natasa Chondraki, a participant in the Polytechnic uprising, said to Unicorn Riot during the 50th anniversary, “One drama after the other escalates. To what extent? For how long? And how many people are going to pay for that? If I were younger, which I do feel that I’m still very young, I would think very seriously of leaving the country.”

For more media from Greece, see our Greece archive page.

Resources for timeline: Avgi, Protagon, Tanea.

Cover image by Niko Georgiades for Unicorn Riot — top three images taken on November 17, 2023 and bottom two on November 17, 1973.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: