Greek Seas: Europe’s Largest Migrant Cemetery

‘Fortress Europe’ is killing thousands of people seeking asylum

An Egyptian boat set sail from the city of Tobruk, in Libya, on June 9, 2023. The overcrowded Adriana is carrying more than 600 refugees from Pakistan, Egypt, Syria and Libya. The vast majority of them are held in the cargo hold. Some will pay an extra $55 to — luckily — travel on deck.

Hellenic (Greek) Coast Guard and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (commonly referred as Frontex) spot Adriana in Greek SAR (Search and Rescue zone) on Tuesday morning, June 13, and start monitoring its movement. It’s another ship with poor infrastructure that will pass through Greek waters destined for Kalavria, Italy. However, its story ends up differently.

A call from the boat was made to The Med Alarm Phone, an emergency hotline for refugees in danger at the Mediterranean Sea, stating that the boat is in distress. Based on information from Frontex at 09:47 UTC, the ship was navigating north-east at slow speeds of 6 knots. Several calls were made and the first was received at 12:17 GMT, a few hours after Greek authorities had spotted the ship.

After the first call, three boats reached Adriana in attempts to provide help. The first one, Lucky Sailor, after being enlisted by the Greek coast guard, provided food and water around 15:00 local time. The Greek coast guard visits the ship a few minutes later and reported that the boat is moving.

Based on Marine Traffic data that BBC have verified, more than two hours later, around 18:00, a ship called Faithful Warrior that was located in the same spot as the Lucky Sailor and also enlisted by Greek authorities, provided some more food and water to the refugees calling for rescue.

While the refugees contact Alarm Phone, the smugglers in charge of Adriana deny rescue and any other help from the Greek authorities. In most cases they are paid after the transfer is complete. According to the coast guard, when Greek authorities offered to help the ship, people on board replied that they didn’t need any help and that they just wanted to continue their journey to Italy.

Read: Distress Hotline Volunteer Speaks on 500+ Dead from Pylos Shipwreck – Sept. 2023

However, the boat is clearly in distress; in fact it’s barely moving. The Greek coast guard insists on stating that the boat was moving with a steady speed, from 19:40 until 22:40, in order to explain why it didn’t intervene earlier for a rescue mission.

The vessel of the Greek coast guard operating in the area, named ΠΠΛΣ-920, is equipped with two state-of-the art thermal cameras. However, the coast guard stated that the cameras were not active during the rescue operation. Moreover, Frontex recommended the use of such cameras and the continuous recording of operations as early as 2021 in a letter to the Greek authorities.

The operating coast guard vessel was 90% funded by Frontex itself and had to follow these orders. The coast guard claims that the cameras were not working because the attention of its officers was focused on the rescue operation. However, according to the Solomon research team, the cameras with which the ΠΠΛΣ-920 is equipped are capable of monitoring without continuous human handling, and therefore the ship could be aligned with Frontex instructions.

Eleven hours after the initial call of a passenger to the Med Alarm Phone for help, the boat sunk around 02:00 on July 14 with the pin being close to Pylos at 36°17.6Β and 021°03.17Α. This spot was only 3.3 miles away from where the boat was first spotted by the Greek Coast Guard.

“The location was within the Greek search and rescue zone and therefore Greece was obliged to rescue. But beyond that, once the Greek coast guard vessel was in the area, they were obliged to rescue under International Maritime Law, which obliges any coastal vessel to intervene in the rescue so that no lives are lost at sea,” says Giannis Skenderoglou. Giannis has been a rescuer at sea since 2016, having contributed to rescues of refugees in the islands of northeastern Aegean sea, while now located and working in the Central Mediterranean.

In order to learn more about the current international maritime legal framework, Unicorn Riot spoke with Danae Angeli, lawyer and member of the The Initiative of Lawyers and Jurists for the Pylos shipwreck in the Athens Bar Association. According to Angeli, when a boat is in danger at sea there is an explicit obligation to rescue it.

“International rules stipulate that a vessel is in danger when the lives of its passengers are at risk. It is not required to be sinking at that moment. Even the possibility that lives may be at risk is enough. In this case (i.e. the Pylos shipwreck), under international law the vessel was certainly in danger,” she explains. “The vessel did not have the safety conditions, there were no life saving equipment on board, it was overcrowded, it was out of food, the engine was broken down, etc.”

Angeli noted that all these factors highlight the need for an immediate rescue by the Greek authorities which “did not happen in this case.” She added, “The Greek authorities may claim that the boat was floating or that the people did not ask for help, but this is not a determining factor. The fact that a vessel is floating does not mean that it is not in danger at any time because there are all the other criteria of whether it is in danger.”

The shipwreck ended up with a total of 104 survivors and 82 dead, while the number of the missing people remains unknown with some estimates of around 500. In accounts captured by Reuters and Kathimerini, nine rescued refugees reported separately that the ship sank when the Greek coast guard put a tow rope on and attempted to move the vessel outside of Greek waters, towards Italy.

According to Skenderoglou, the use of such a rope is highly prohibitive in rescue operations. “Neither a rescue, nor any other operation should be carried out using a tow rope” he told UR. When we asked him what his rescue team would do in a similar situation he replied:

“In case there are large boats in the area, we would ask them to stand as a “shield” in any weather conditions to create the right conditions at the rescue site. With our rescue boats we would approach to control the situation and create confidence in the people, with the help of our translators. The most correct and safest rescue operation is from the stern, from where we would slowly transfer people to the ship.”

After the Shipwreck

After the shipwreck, the survivors were taken to the city of Kalamata in Southern Greece. There, the Greek authorities arrested 9 of them, all of whom are Egyptians, as the alleged traffickers, who were charged with serious offenses, such as illegal trafficking, causing a shipwreck and negligent homicide. Many of those arrested were identified by other passengers as the traffickers.

However, these arrests may not be enough. “The plan is to pin the blame on some traffickers. To put all the blame on them and end the case,” Petros Konstantinou, coordinator of KEERFA (United Against Racism Movement), tells UR. He explained that these traffickers are simply the scapegoats of the policies adopted by the Greek government and the coast guard, which are the real cause of the shipwrecks, such as the one in Pylos.

The survivors of the shipwreck, after Kalamata, were taken to the Reception and Identification Center (RIC) of Malakasa (Malakasa Refugee Camp), a locked facility where many are still being held to this day.

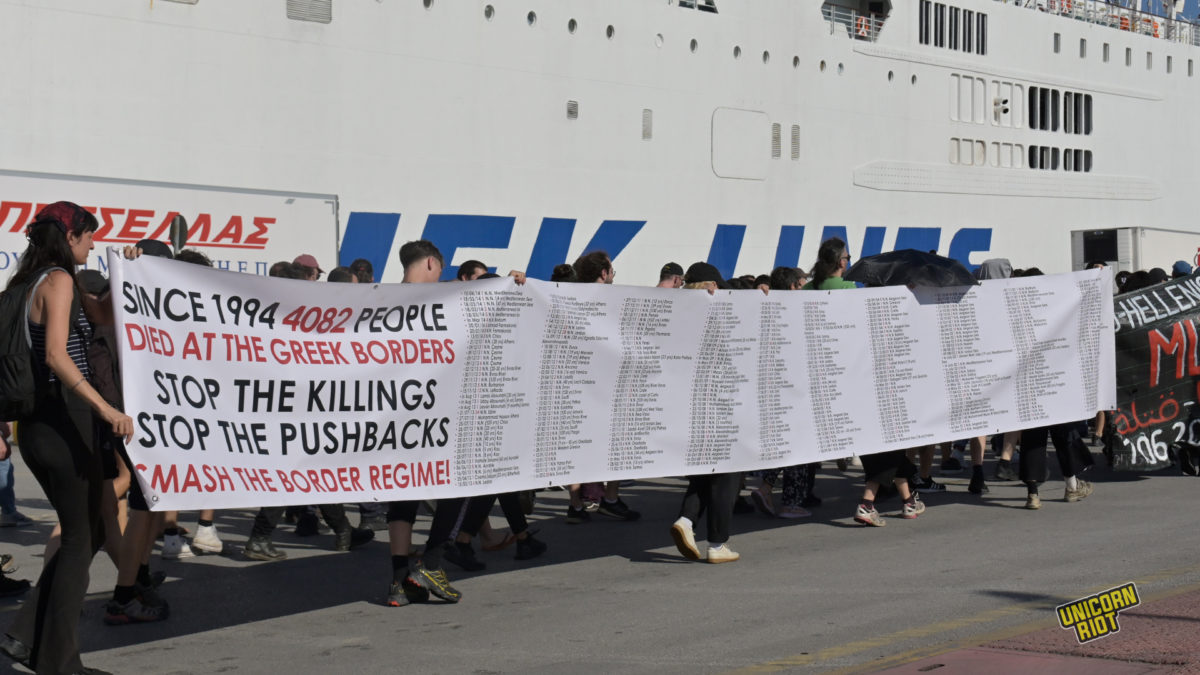

The shipwreck of Pylos was followed by protest marches in all the country’s major cities. On June 15, one day after the tragic event, thousands of people demonstrated in downtown Athens against the policies that led to the shipwreck and in solidarity with the refugees.

A few days later, on June 24, people gathered outside the camp in solidarity and support for the rescued refugees, some of whom they managed to talk to. Konstantinou said that KEERFA is “in contact with the survivors and we are asking for solidarity for what happened from the international movement.” He didn’t stop there however, Konstantinou called for mobilizations against “the choices of the Greek state” and to initiate a “campaign for open borders, to bring down the border fences, for papers to refugees and migrants. We are on the side of the victims and against any attempt to cover up these tragic events.”

Fortress Europe – Aegean and Fences

In 2015, more than 850,000 people arrived in Greece from Turkey crossing the Aegean Sea. Most of them refugees coming from Syria and Afghanistan, traveling for several days, crossing small villages of Turkey, and then getting on a boat to hopefully arrive in Greek territory. Some of them arrive on the Greek island of Lesbos (Lesvos), and then they head north to cross the borders, but some don’t.

In 2015 alone, 799 people were reported dead or missing on this deathly route. Since 2015, over 2,000 persons seeking safety have died or gone missing in their attempt to cross the Eastern Mediterranean route, according to data from the UNHCR.

The so-called “Balkan passage” came to an early end after just a few short years. The refugees arriving on Lesbos from Turkey don’t visit Athens and a Northern European country anymore. Instead, they will stay trapped in restrictive closed detention camps.

Countries such as North Macedonia, Bulgaria and Hungary then started building border fences. Greece has its own policy for anti-migration fences and is currently extending the Evros fence at the border with Turkey with an additional 35 kms at a cost of €99.2 million. The measure brought forth by the right-wing government has also been accepted by the liberal-left wing party of SYRIZA.

These methods of deterrence havn’t prevented thousands from continuing their attempts to make it to Europe. In 2023, one-fifth of arrivals are children, while almost half of them are below the age of 12. Twenty seven percent of all children were registered upon arrival as unaccompanied or separated.

EU-Turkey Agreement and Drift-Backs

The EU-Turkey deal is an agreement between European Union (EU) members and the Turkish Government signed back in March 2016. The main point of the deal was that every refugee who arrives “irregularly“ from Turkey to a Greek island will be returned to Turkey. For every refugee that will be returned, the EU would accept another that was waiting in Turkey’s refugee camps.

Additionally, the EU funded Turkey with €6 billion, in a pact that was criticized for the way that the European Union treated asylum seekers like exchangeable numbers rather than people who fled from a war produced by NATO allies.

People arriving in Greek waters have to deal not only with the sea, but with the Greek coast guard and Frontex.

Between March 2020 and March 2022, Forensic Architecture investigated the practices of the Greek state in the Aegean Sea and revealed that 27,464 people traveling across the Aegean to Greece from Turkey have faced drift-backs — a policy that involves a life-raft or inflatable boats with no engine, through which people on floating vessels on the water are not rescued but are pushed back to Turkey. Drift-backs are also called pushbacks which include ground and water.

Forensic has verified over 1,000 cases of drift-backs and created an online platform for these verified events. Drift-backs have become well-practiced for the Greek coast guard and Frontex is aware of more than 417 cases, noting them in their own archives as ‘preventions of entry.’ New York Times published a video from such an operation conducted on April 11, 2022, in Lesbos.

One of the events noted in Forensic’s platform is close to Pylos where the shipwreck took place. On May 11, 2021, at 01:40, 44 asylum seekers onboard a sailing vessel in distress were rescued in rough weather conditions by the Greek coast guard who towed them to a location off Kalamata.

The distressed vessel was then driven eastwards for approximately 12 hours by a larger coast guard vessel with masked ‘commandos’ onboard who reportedly beat and intimidated the asylum seekers. They were eventually forced onto two life rafts and cast adrift before they were picked up by the Turkish coast guard off the coast of Datça, Muğla.

Pushbacks Made the Kalavria Route

Τhese practices of deterrence have made it almost impossible for refugees to reach Greece, and that was a publicly announced goal of the government: refugees are not welcomed in Greek islands.

Smugglers paid by those who want to flee to Europe invented a new route in 2021, the route of Kalavria. Boats from Turkey start a much longer and more dangerous trip crossing the whole Aegean trying to stay in international waters, so as not to be intercepted by the Greek coast guard. However, it is unclear whether smugglers have such a great understanding of sea maps and maneuver techniques.

The Greek government’s policy on the refugee issue reflects a so-called prevention plan. From the aforementioned Evros fence to the pushbacks in the Aegean Sea, this plan tries to prevent any attempt of refugees/migrants to enter the country.

According to KEERFA coordinator Petros Konstantinou, these types of policies, both from Greece and the EU, are responsible for the death of people, as happened in Pylos. “These types of policies push refugees into the hands of the traffickers, who have now established the so-called Kalavria route as the only passage. What happened off the coast of Pylos is a crime at the hands of the Greek coast guard.”

If the ships want to end their trip in Italy, the Greek coast guard routinely fails to intervene and acts like there is no ship. That’s the same route that ended up in the shipwreck near Kythira in the summer of 2022. That’s also the case of Adriana, with the exception that the boat departed from Libya.

As with the pattern of the many reported drift-backs, a boat with more than 600 people seeking asylum is not welcomed by the Greek authorities. Adriana had to be pulled in another destination.

Investigation Started into the Pylos Shipwreck

The Greek justice system launched an investigation into the Pylos shipwreck, pledging to examine the role

of the Greek coast guard. Some survivors allege they were pressured to conceal the coast guard’s responsibility. Victims’ relatives, survivors, and attorneys filed a petition for the wreck to be raised and the recovery of hundreds of bodies from the seafloor.

As this long journey towards uncovering the truth and accountability continues, the exact number of deaths in one of the deadliest refugee shipwrecks in modern history in the Mediterranean will remain unknown.

Cover image of a protest on June 21, 2023, in Thessaloniki, Greece in solidarity with refugees and migrants after the Pylos shipwreck, contributed by Thomas Giotopoulos.

Related:

Distress Hotline Volunteer Speaks on 500+ Dead from Pylos Shipwreck [Sept. 2023]

Greece’s First Housing Squat for Refugees & Migrants, Notara 26 [May 2018]

Life Vest Mural Draws Attention to the Plight of the Refugee [Nov. 2021]

Go Game [Film] [Feb. 2022]

Crisis: Borderlands [March 2017]

For more from Greece, see our archives.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: