Kendrick Lamar in Africa – Big Stepper’s Heritage Plug

The following article is a cultural commentary on the music career of American rapper Kendrick Lamar, and how his tours of the African continent has influenced his music. The views and opinions expressed within do not necessarily reflect those of Unicorn Riot.

Kendrick Lamar’s hip hop career is a never-ending attempt to go back home. Despite American novelist Thomas Wolfe’s singular warning, “You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your romantic love, back home to a young man’s dreams of glory and fame” or “back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting but which are changing all the time,” the highly regarded rapper wants to remember and return to his grounded place with each new album.

But Kendrick soon finds, like many a prophet before him, that the direction home is not so much a circle as it is a road with a thousand forks. His moments of duality are neither the rights and wrongs of his cruel self-probing nor the tension between the Black prophetic mantle and the bright lights of Hollywood. The ultimate duality is that home is split in itself. Whether home means Compton on “good kid, m.A.A.d city” (2012), Africa on “To Pimp a Butterfly” (2015), ego on “DAMN!” (2017) or family on “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers” (2022), its contours never settle in time to welcome the native.

On the Black Power masterpiece “To Pimp a Butterfly,” the question is never decided whether the often repeated phrase, “I came home,” refers to Compton or Africa. Kendrick knows this. That’s why a giant map of Africa labeled “Compton” provided a backdrop for his recent performance in Rwanda. The Compton native was back in the Bright Continent to headline the inaugural Move Afrika concert at BK Arena in Kigali, Rwanda, on December 6 and Hey Neighbor Festival at Legends Adventure Farm in Pretoria, South Africa, on December 9, 2023. He was back home for the third time, having previously toured South Africa in 2014 and visited Ghana in 2022.

Kigali, Rwanda

Mr. Morale kicked off his Rwanda performance to the full-throated African drums of his 2022 album opener, “United in Grief.” The crowd ecstatically sang along to “N95,” performed second in order of the tracklist. Making good on its rejection of digital civilization, the song was greeted with the life-size fabric placing Compton at the center of Africa, complemented with stage lighting, filtered overhead through multi-colored Agaseke baskets by Nyamirambo Women’s Centre and Kitenge fabrics by Dolf Benza and Stufish. The Pan-Africanist backdrop was, of course, a relic from Lamar’s iconic 2016 Grammy performance.

After crowning his five Grammys with performance of the night credit then, Kendrick told the Recording Academy that he had written “To Pimp a Butterfly” under the stimulus of his 2014 tour stop in South Africa. The recollection equally explained his choice of backdrop that night: “I felt like I belonged in Africa. I saw all the things that I wasn’t taught. Probably one of the hardest things to do is put together a concept on how beautiful a place can be, and tell a person this while they’re still in the ghettos of Compton.”

A few times between his 70-minute Move Afrika performance on December 6, Kendrick stopped the music to appreciate his spectators, mostly from Rwanda but also neighbors, Kenya and Uganda. “It’s my first time on stage in front of my people,” he told the 10 000-seater BK Arena, deep-diving into confessions and epiphanies along the set. “Every individual here, y’all truly inspired me and I’m sure everyone on my team feels the same way,” he said but reserved special thanks for his spirited steppers, ballerinas and child dancers, hired from Rwanda’s Sherrie Silver Foundation for the occasion, his fellow performers, including DJ Toxxyk and Bruce Melody, also from the host country, and Zuchu from Tanzania.

Where TPAB is concerned, Oklama was understandably high on his own stash. “‘To Pimp a Butterfly!’ If I recollect properly, the reason of this album was because of Africa,” he said in between a TPAB section that started with; “King Kunta,” followed by “i,” “Institutionalized,” “The Blacker the Berry,” interrupted by “Love,” dedicated to Rwanda for the occasion, and closed by “Alright.”

Some 12 Rwandan rappers, including Kivumbi King, Pro Zed, Angel Mutoni, Joe Logan, Bruce the 1st, Kenny Kshot, Maestroboomin and Prime got to pick Kendrick’s brain before the Kigali concert, while some went on to curtain-raise for him after President Paul Kagame’s speech. The young artists treasured nuggets from the “brother time,” including the Compton emcee’s advice to “…like yourself and be comfortable in positions of fear.” For his part, the “Savior” rapper wants to be “to be fearless in every word that I say, to be child-like” so creative ideas come his way.

“I was saying to your local artists when I started doing music, I was just doing music for me, talking about my experiences, where I come from, giving medicine to the people around me that was going through things. That was the whole inspiration behind ‘good kid, m.A.A.d city’,” Mr. Morale went into “brother time” again at BK Arena.

“Many years from that day, I wouldn’t have known I would be in Rwanda, Africa. But not only I am touching people in my community, but I am touching people right here,” he intimated. “I think from the moment I started writing, without me even knowing, subconsciously, my whole purpose was to evolve and learn myself and find myself and continue understanding who I am. And removing the perception of who I’m perceived to be, I’m still learning to this day,” explained Mr. Morale.

Towards the end of the show, Kendrick shared an epiphany in which his life was reflected in a young Rwandan interlocutor. Notably, the 2015 album owes some of its deeper cuts to Oklama’s mythic encounters in South Africa: the young boy who turns out to be his ancestor in “Momma,” the old beggar who turns out to be God in “How Much a Dollar Cost” and the “ghost of Mandela” at Robben Island Prison in “Mortal Man.” “No matter where you’re around the world, if you really mean what you say, it don’t matter where you at; you gon’ respect, you gon’ feel that shit,” Kendrick repeated his exchange with the young man from the meet and greet.

Move Afrika, a partnership between Global Citizen, a humanitarian agency, and Lamar’s at-service company, pgLang, will be held annually in Africa to “promote health and equity, defend our planet, and create jobs and economic opportunity.” 70% of Move Afrika concert tickets were exchanged for humanity-improving services, including healthcare, agriculture and climate action. According to Global Citizen,1,000 trees were planted as part of the inaugural Move Afrika event.

President Kagame of Rwanda addressed the crowd before Kendrick’s performance. “What a good way of ending the year, with music, with energy, with optimism!” Kagame said. “I want to dedicate this moment to the community health workers who keep us healthy,” he added.

Nelson Mandela’s grandson and Global Citizen chief vision officer, Kweku Mandela, said Move Afrika aimed to create a “robust touring circuit to the continent,” especially since Africa is usually omitted from the global touring commitments of pop notables. “We are putting a marker in the sand around live touring events and showcasing the creative economy on the African continent – you’re talking about the world’s youngest population, over 700 million people with the median age of 19,” Mandela said.

Pretoria, South Africa

For South Africa, Kendrick took a different visual approach, performing in front of giant fabric resizes of critically acclaimed American artist Henry Taylor’s acrylic-on-canvas paintings. Taylor’s talents, previously tapped for the limited-edition vinyl release of “DAMN!” single “DNA,” have already been a notable feature of the record-grossing Big Steppers Tour. For Hey Neighbor Festival, Kendrick used four Taylor paintings, “Resting” (2011), “Sweet” (2013), “The Love of Cousin Tip” (2017) and “‘Batman’ Part Alien” (2018) as his backdrops.

Mostly themed around the Black family, the paintings are also inside-captioned Los Angeles and California, Kendrick’s city and state. Both photos for “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers” album art are a possible nod to “Resting.” In the painting, this is captured in a “No Warning Shots Required” sign in the young couple’s background and a list of items for an imprisoned relative on the table, while Kendrick’s own “resting” on his inside art embodies tension, just as his family photo gives away a gun and a diamond crown of thorns.

Taking up the TPAB theme from the Kigali concert, Kendrick told his South African hosts how the country lit his fire when he painted his masterpiece. “It was 2014, the first time I came to South Africa, right? And that shit inspired a particular album, one of my favorite albums. ‘To Pimp a Butterfly’! Beautiful! I said when I go back to the city, I got a story; I got some inspiration; I gotta tell both sides of the page, huh? I tried my best to make it all make sense. I think it’s a decent album,” he told a proud crowd in Pretoria.

Having previously performed in Cape Town, Durban and Johannesburg, Kendrick was in Pretoria for his second dance with South Africa. The Heineken-powered and unity-themed Hey Neighbor Festival featured Khalid, The Chainsmokers, Swedish House Mafia, H.E.R. and South African stars including Nasty C, Musa Keys, Zakes Bantwini, Mafikizolo and Tyla of “Water.”

You Can’t Go Back Home

In the Argentinian movie, “The Distinguished Citizen,” a homecoming Nobel laureate must put up with local artists and politicians who demand his public endorsement for their narrow interests. He will soon find that, “You can’t go back home,” as Wolfe warns in his novel of the same title, “to singing just for singing’s sake, back home to aestheticism, to one’s youthful idea of ‘the artist’ and the all-sufficiency of ‘art’ and ‘beauty’ and ‘love’ … away from all the strife and conflict of the world.”

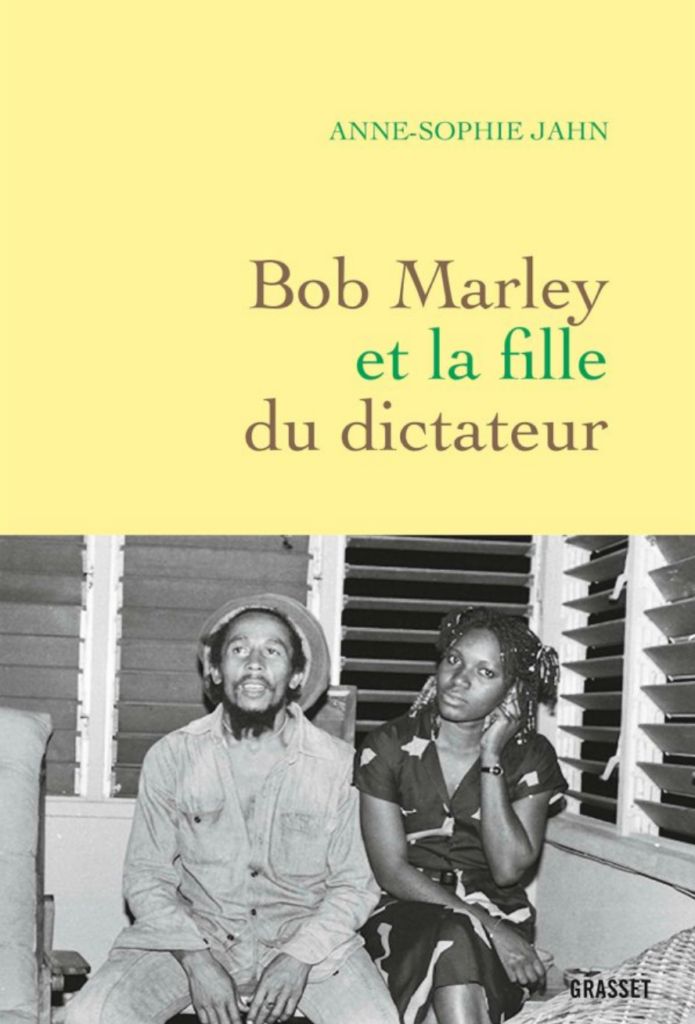

Beginning with Bob Marley in Gabon, homecoming Pan-Africanists will soon find their love of the people and nostalgia for the mother continent complicated with governance problems at home.

Kendrick’s homecoming too, has not been without controversy. A BBC article describing the Kigali concert as a “soft power” move by Rwanda, a country recently ruled an unsafe haven for refugees handed down from Britain because of its poor record on human rights, set off an echo chamber. Widely seen as the West’s favorite dictator for maintaining social and economic stability beyond his country’s fractured past, President Paul Kagame maintains a chokehold on free speech and incarcerates opposition activists.

A disciplinarian and diplomat, Kagame has also been the envy of dictators who seek economic benefits from good relations with the West without ceding the civic space.

In Zimbabwe, his admirers have been engaged in a public relations campaign whereby international celebrities, including American rapper Rick Ross, American boxer Flyod Mayweather and South African actress Pearl Thusi, have been reportedly paid to make public appearances with a flag-scarf associated with the ruling party.

However, one does not lightly pass Kendrick’s African jeremiads for romanticized nostalgia. Mr. Morale’s raps can, indeed, be thought of as a “critical home theory” – with home representing all that is sacred and innermost, from the ego, to the family, the hood, the culture and the race.

A master of duality, Kung Fu Kenny’s steel cuts both sides, so that songs like “i” and “u,” “Alright” and “The Blacker the Berry” sit side by side. To hear psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud tell it, “I believe that when poets complain that two souls dwell in the human breast, and when popular psychologists talk of the splitting of people’s egos, what they are thinking of is this division… between the critical agency and the rest of the ego…” Lauded as the voice of a persecuted people, Kendrick has also been accused of victim-blaming, particularly for the racially charged “The Blacker the Berry,” which calls out community violence. But one aspect of being Kendrick is that neither himself nor his own are simply forgiven for belonging home.

Kendrick’s “Humble” bragging, “Get the fuck off my stage; I am the Sandman,” evokes the classic American character of the Apollo Theater but the rapper could be a closer relation of Freud’s Sandman. The psychoanalyst used the German novel, “Sandman,” by E.A Hoffman to develop his theory of the uncanny, defined as a frightening encounter with an oddly familiar feel. Freud stresses the German word for uncanny, “unheimlich,” to explain the uncanny as the unsettling vibe unconcealed out of homely situations. Kendrick is no stranger to the uncanny, if only because of his last album’s prelude video, “The Heart Part 5,” whose character-morphing deepfakes stress the signature, “I AM ALL OF US.” Aside from the 2022 video, the rapper makes extensive use of doubles and epiphanies not just to make peace with his demons but also to sustain a critique of his own environment.

Freud’s “unheimlich” can be extended to the Rwanda concert where Sherone Silver Foundation dancers’ automated vibe and uniformed force-like outfit, against Lamar’s gold-embellished black suit, gave off the optics of Africa’s officialdom, not least Rwanda.

In “United in Grief,” Kendrick runs off a checklist of his acquisitions, describing it as his way of “grieving different,” a coping mechanism for generational trauma. African heads of states, typically decolonial orators, also “grieve different” with a keen taste for colonial capitals, commodities and customs.

The opening subtitles of TPAB video, “For Sale,” “They say if you are afraid go to church; but remember he knows the Bible too,” set the stage for “The Heart Part 5.” “He,” of course stands for Lucy (Lucifer) interchanged with the industry and Uncle Sam throughout “To Pimp a Butterfly.” In other words, the system pressing African-American people down also wills itself to speak the language of their environment – a continued cycle of cultural expropriation. This is Kendrick’s basis for refusing fixed narratives, political correctness, cancel culture and finally self-immolating his Black prophetic statue on “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers.” On “The Heart Part 5,” Kendrick wants to “go to church” and whom does he expect there but the devil with his finger on a Bible quote? He puts the culture on blast because, though we have come to think of it as sacred and innermost, it has also been appropriated, corrupted and shot through with generational curses.

New Butterfly on the Radar?

It is interesting to parse the impact of Lamar’s latest Africa tour in terms of potential music. K.Dot had rapped about “racing with Marcus Garvey on the freeway to Africa” on “Section.80”’s “HiiiPower” but when manager Dave Free came to organizing his 2014 shows in South Africa, nobody in Lamar’s record label TDE had background information on the continent, aside stereotypes soaked up from public education and the media. Looking back on the experience in a 2017 interview with comedian Dave Chappelle, Lamar described his tour stops in Durban, Cape Town, Johannesburg as his “I’ve arrived” shows.

“This is a place that we, in urban communities, never dream of,” Lamar said. “We never dream of Africa. Like, ‘Damn, this is the motherland.’ You feel it as soon as you touch down. That moment changed my whole perspective on how to convey my art.” Returning to L.A, Lamar would cancel three albums worth of music and build a new album around the Bright Continent.

Free recalled Kendrick’s call to him from South Africa, in a 2021 interview with the Big Hit Show podcast. “Bro, I just went through a village,” Lamar told Free. “I never felt that much love in one place. Just love, like the energy of that.” At Robben Island Prison, Lamar sat in Nelson Mandela’s cell, immersing himself in the spirit of “Mortal Man.”

“I remember going inside that cell and you know the way I felt and how humble I was,” Kendrick said on the same podcast in 2021. “You know that this man that was fighting for equality served 27 years, 18 months in that little cell but still kept his mental capacity and still kept his integrity and his enthusiasm to motivate not only himself but the people around him. It inspired me a hundred percent.

“And I kind of took that experience and looked within myself for my own experiences. Okay, I come from a background of a neighborhood that wasn’t so much perceived to be great but I can’t let these four corners define who I am or define who my homeboys are.

“You know, so I took that experience, man, and the whole concept about ‘To Pimp a Butterfly’ was to share that experience with them. To go back to Compton and to tell them what I have learned. It was me explaining my experiences and what emotions it brought up from those experiences. And tell them, ‘Y’all, it’s something bigger than Compton where we from,'” Oklama explained.

If Kendrick’s 2023 African tour speeches stress the impact of the Bright Continent on his career, his biographer, “The Butterfly Effect” (2020) author Marcus J. Moore readily agrees. “Ultimately, South Africa played a significant role in Kendrick’s career, and in many ways, the time he spent there helped redirect the course of mainstream Black music If he hadn’t taken that trip, or opened his eyes to the country’s grand splendor, there’d be no ‘To Pimp a Butterfly.’

“Free and avant-garde jazz might still struggle to attract bigger groups of fans, and sonically challenging art might still be relegated to smaller venues. South Africa set the stage for Kendrick’s greater act. It also allowed him to return to where it all started, this time with a clear head and a full heart.” And, perhaps, there would be no “Black Panther” soundtrack, at least not in the form that Kendrick curated it.

Three years after TPAB, Lamar brought together South African music acts, Yugen Blakrock, Sjava Babes Wodumo and Saudi with more established American artists for the “Black Panther” soundtrack. As Move Afrika expands its footprint on the home soil, more studio collaborations with Africa’s globally outbound music scene will definitely be game-changing.

Onai Mushava is an independent Zimbabwean journalist and writer who regularly covers African politics, arts and culture. You can read his previous articles on Zimbabwe’s ongoing electoral crises below:

Zimbabwean Opposition ‘Disengages’ From Parliament in Protest of ‘Illegal Recalls’ – October 26, 2023

Zimbabwean Government Mounts Post-Election Propaganda Campaign – October 12, 2023

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.