Shipwrecked Synthesizers: How Electronic Music Came to Cabo Verde

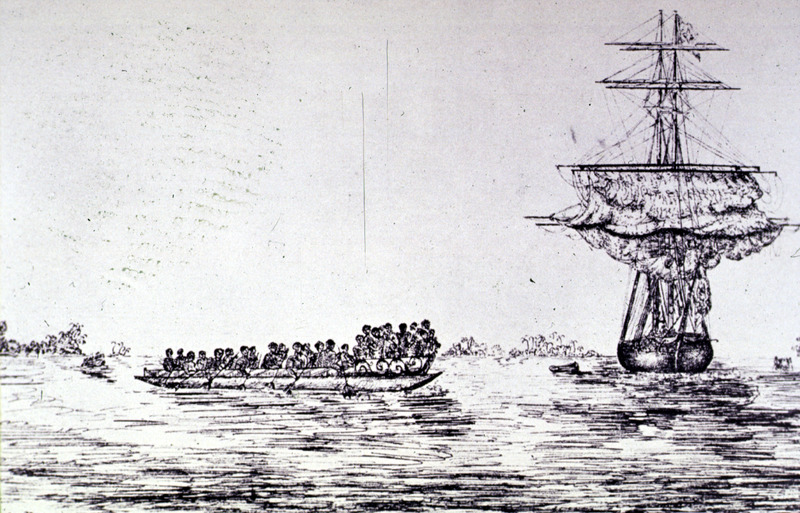

The archipelago of Cabo Verde had already been colonized by the Portuguese for hundreds of years in 1968 when a ship was discovered marooned on the São Nicolau island. To the surprise of local villagers in Cachaço, the ship was stranded eight kilometers from any of the isle’s coastline.

Disclaimer: The shipwreck anecdote has been subject to debate on whether it is myth or an oral history passed down by griots.

What they didn’t know at the time was the ship had embarked on a journey from the Baltimore harbor to the EMSE Exhibition (Exposição Mundial Do Son Eletrônico) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The expo was the first of its kind and was poised to present the newest synthesizers and electronic gadgets in the up-and-coming South American market spearheaded by Brazil and Colombia. Many of the leading companies in the field of electronic music agreed to participate and companies like Rhodes, Moog, Farfisa, Hammond, and Korg all packed up instruments to add to the cargo ship’s manifest.

Some reports claim passengers on board knew the route, given it had been traveled many times. If anything, for them, the passage should’ve been an easy one – boring, even. Other oral histories say it was a ghost ship and never intended to have any passengers. Even still, villagers were perplexed at the arrival of the unmanned vessel and after much deliberation and consultations with the village elders, they decided to open the containers to see what was inside.

But before they were able to move forward with their plan, the Portuguese colonial police arrived and secured the area. By this time, people from around the islands started to hear the news of the wreck, and excitement about what could possibly be inside began to mount. After a few trials, welders arrived on the scene, ready to pry open the heavily secured containers. Hundreds of boxes awaited their fate but enthusiasm and anticipation quickly dissipated once they realized all of the containers were just keyboards and other instruments which they had never seen before and moreover, proved useless to them considering few islands had electricity.

The Portuguese police, who had already banned local music styles like traditional morna, coladeira, and Funaná, decided to lock up the instruments by storing them in the basement of the local church – who knows, maybe the Americans would come back for them. “During the time I grew up in Cabo Verde, we were colonized by the Portuguese,” recounts Funaná artist Telo Peres in the ‘A Sweet Pain’ mini-documentary, “Certain things could not be said; certain things could not be sung. There was a lot of repression and we musicians could be punished if we were caught playing Funaná.”

“I myself was a victim in all of this,” Peres continues. “I was able to make music, I was able to rehearse with friends, even if it had to be in secret. For that reason, I was beaten many times.”

But even the looming threat of violence didn’t stop Verdeans from finding ways to enjoy themselves, namely with music “The Portuguese didn’t want to see the people happy or having fun,” claims Peres. “Funaná works as protest music, it is music against repression. And for that reason, the Portuguese didn’t like it because it’s music that expresses the joy of a people.”

Peres goes on to explain that when slaves escaped, they would hide in the mountains of Cabo Verde, knowing the Portuguese kept to the lowlands.

And it was in these mountains that an army began to grow.

Growing Unrest

There had been tension between the Verdeans and the Portuguese presence for many years before the synths were shipwrecked on São Nicolau. At the time, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) had been part of many violent guerilla attempts to free Portuguese Guinea and Cabo Verde from Portuguese control.

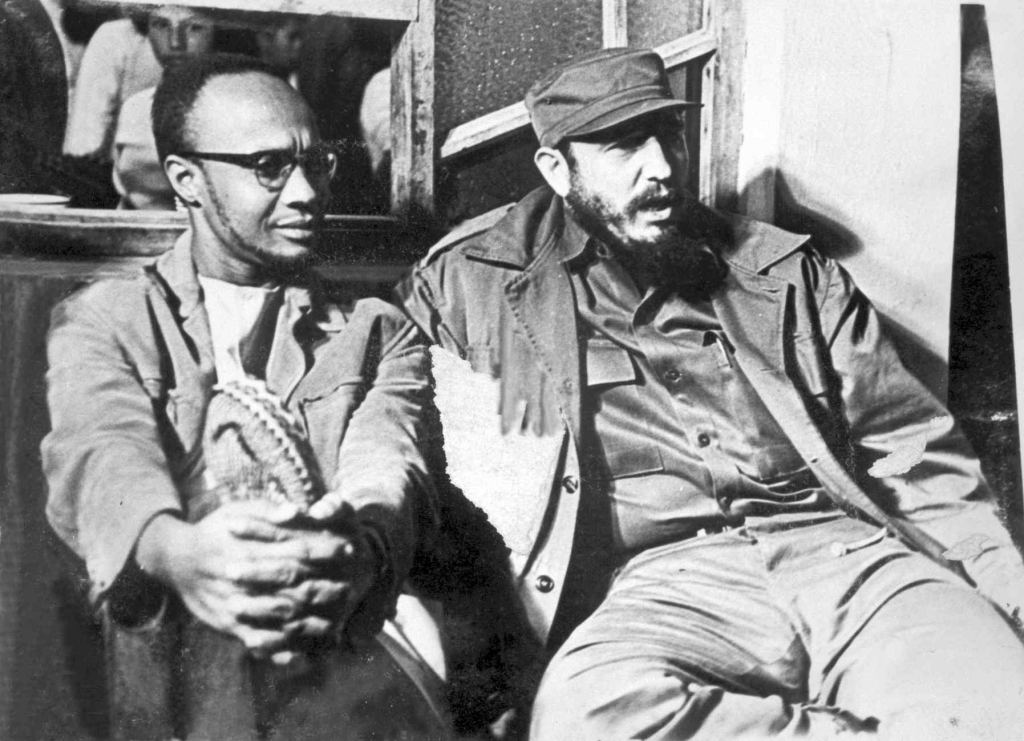

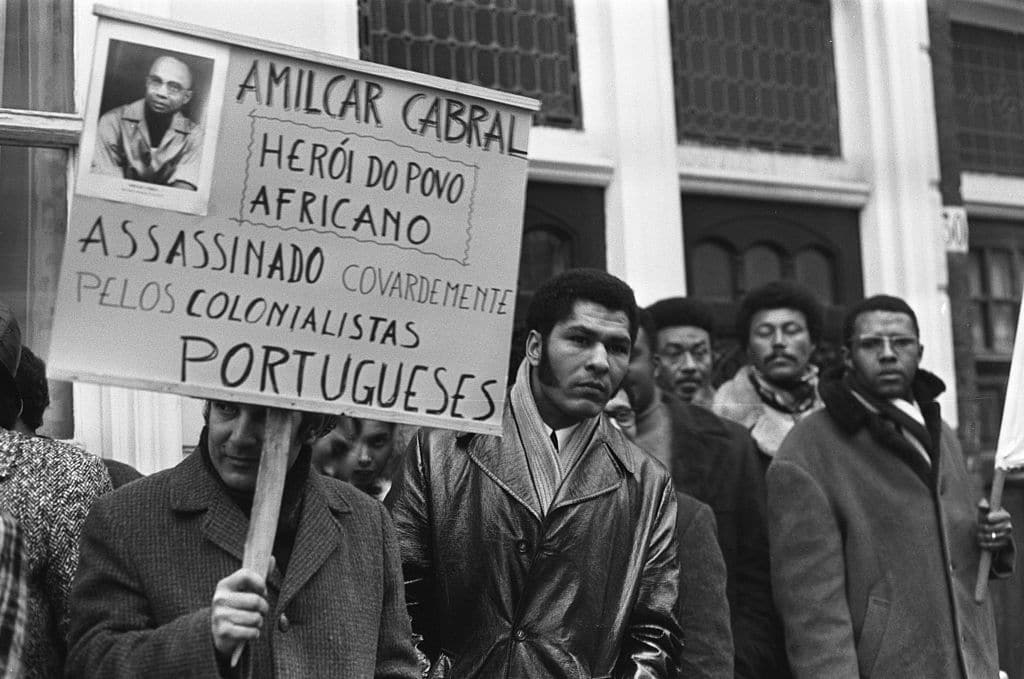

Initially formed peacefully in 1954 by anti-colonialists Amílcar Cabral and Henri Labéry, by 1959, peace for the PAIGC was no longer an option when Portuguese soldiers opened fire on dockworkers, killing 50 innocent people in the Pidjiguiti massacre. After this event, Cabral gained more support for the PAIGC from locals in both Guinea and Cabo Verde.

For nearly 15 years, Portugal saw no threat in the PAIGC and essentially ignored the population’s growing support of the movement. However, Cabral used this oversight to his advantage.

Using guerrilla warfare, the PAIGC continuously made attacks against Portuguese forces beginning in March 1962 and continuing on until the mid-70s. For logistical reasons, most of the attacks were largely concentrated in mainland Guinea but on the islands of Cabo Verde, Cabral, and the PAIGC moved more clandestinely.

After Cabral made friends with Fidel Castro in 1966, Cuba agreed to supply artillery experts, doctors, and technicians to assist Cabral in his quest for independence. By 1967, the PAIGC had carried out 147 attacks on Portuguese barracks and army encampments until they could effectively control two-thirds of Portuguese Guinea.

“It’s called a guerilla war because it came from Africa and our leader, Amílcar Cabral, was an expert,” explains Peres in the documentary. “He knew we were outgunned but saw that we knew the land better than the Portuguese and that we wanted it more than they were prepared to give.”

But Portugal wasn’t about to give up their territories so easily. In an attempt to gain favor, Portugal, still ignoring the effectiveness of the PAIGC, began a new campaign against the guerrillas.

Instead of battles, they brought in António de Spínola to govern the colonies. Spínola enacted a construction plan to build schools, hospitals, and new housing as well as improve the telecommunications and road system. These improvements changed the lives of the villagers, although maybe not in the way the Portuguese had hoped.

Hidden in Plain Sight

After the shipwreck, the synthesizers remained locked up seeing that they were of no use to a community without electricity. But once Amílcar Cabral learned about the shipment, he had another idea in mind.

Still banking on the aloofness of the Portuguese to his PAIGC, the anti-colonial leader arrived in the Verdean archipelago and suggested the instruments be distributed equally to the buildings that had access to electricity – most of them being schools.

“Cabral told them to take the instruments to the lowlands,” says Peres, “One of the few places with electricity, saying that ‘no Portuguese will think to look there because it’s in their house.’”

The synthesizers were welcomed in the presence of curious children and young people. Although their music was banned, these young students already had music in their blood and rhythms passed down through generations in their souls.

Once they figured out how to turn the new instruments on, songs began to flow almost immediately. Overnight, Cabo Verde’s youth became the owners and operators of some of the most exciting music technology of that time.

“The old musicians said, ‘No fist is big enough to hide the sky.’” remembers Peres. “These were the men who defied the Portuguese and kept Funaná alive, hidden away – unafraid of persecution if they were caught.”

The synths helped modernize the indigenous folk dances previously outlawed by the Portuguese. For many, the fun was in combining indigenous instruments with Portuguese accordions and now, these new synthesizers.

For years, the Verdean youth tinkered away on their Korgs and Moogs, working out how they functioned and then eventually using them to perform the traditional music of their island. Soon, a unique form of disco emerged, blending traditional morna, coladeira, and Funaná with choppy guitars, Latin rhythms, and cosmic synth solos.

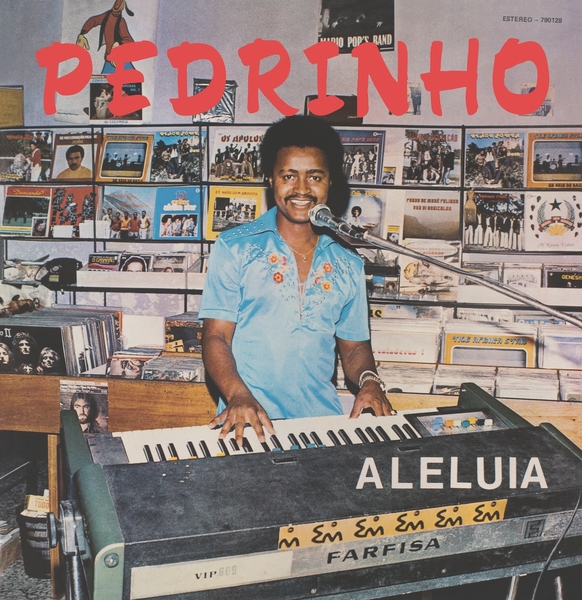

When the students who were gifted synths finally came of age, a cosmic disco wave swept throughout the country. “This new sound slipped past the Portuguese censor,” laughs Pedrinho, another Cabo Verdean artist featured in the documentary. “But we all knew what it was because it filled us with joy and hope.”

As cosmic disco grew in popularity, so did the nation’s independence movement, “Their music was like medicine and their struggle to keep it alive/living was like the battle Cabral’s resistance was fighting,” says Peres. “It was a symbol of a spirit that could not be killed and for that reason, it became the battle cry of our revolution.”

With Cabral leading the way, the PAIGC’s guerrilla movement became one of the most successful wars for independence in modern African history. By 1972, the group controlled much of Portuguese Guinea with Cabral becoming the de facto leader of what is known as Guinea-Bissau today.

However, after a coup within the PAIGC, which is suggested to have been influenced by Portuguese police, Cabral was assassinated.

Despite his passing, Cabral’s movement continued after his half-brother Luís Cabral picked up the reins. With majority control, Portuguese Guinea declared independence from Portugal in 1973, only eight months after Cabral’s assassination.

Independence for Cabo Verde came a little later after a military coup in Lisbon overthrew the authoritarian regime of Estado Novo in April 1974. Called the Carnation Revolution, this allowed for many socioeconomic and political changes, not just in Portugal but in all the Portuguese territories.

After the PAIGC and Portugal signed an agreement for a transitional government, Cabo Verde declared independence from Portugal on July 5, 1975, and Portuguese forces fled the archipelago shortly thereafter. Once colonial rule was lifted, the music which had been banned and played in secret was finally able to be played freely.

“For me, music means sadness but it also means joy,” says Pedrinho. “My song ‘Odio Sem Valor’ is in two parts: the first part says this land has no justice and talks about the injustice and abuse we Cabo Verdeans suffered. And then the next part says, ‘but that’s okay because we can dance the Funaná.’”

Space Echo

During the final years of colonial oppression and the beginnings of Cabo Verde’s independence, a large migration of locals moved away from the islands, given many of them still had Portuguese passports. Because their music wasn’t banned in the European cities they emigrated to, many musicians from the islands decided to record the music they had been playing in secret.

A big community grew in cities like Lisbon, Portugal and Rotterdam, Netherlands and here, these artists got the opportunity to record their traditional music with the help of smaller local labels.

These records, many of them by the young adults who were given access to the shipwrecked synthesizers, were directly responsible for the explosion of traditional music being fused with electronic sonics that happened in the late 70s and early 80s.

A compilation by Frankfurt-based rarities label Analog Africa called “Space Echo – The Mystery Behind The Cosmic Sound Of Cabo Verde Finally Revealed” collected some of the more popular songs from this era on a 2016 release.

The Sound of Joy and Resistance

“The Portuguese have a word that only exists in their language, ‘Saudade,’” explains Pedrinho, who’s not only featured on the Space Echo compilation but was also one of the kids who learned to play music on those synthesizers. “It describes that feeling of longing for something which has gone from you and may never return. The Funaná music of our islands is like the anti-saudade. It expresses our spirit of joy for living.”

That fateful day, when a ship brought synthesizers to their country, created an exciting new scene for Cape Verde’s cosmic disco.

“I often use this story of our music to describe the Portuguese state of Saudade,” Pedrinho goes on to say. “We the savages took their beloved accordion, put our filthy hands all over it, and played it better than them. We made it sing so beautifully that it shattered their concept of civilization. Their ape had taken their instrument and turned it into a weapon against them.”

This music wasn’t just a part of an artistic movement – it was the soundtrack for a movement that would eventually overthrow an oppressive government. Cabo Verde’s cosmic disco is the sound of freedom.

Cover image by Niko Georgiades for Unicorn Riot.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.