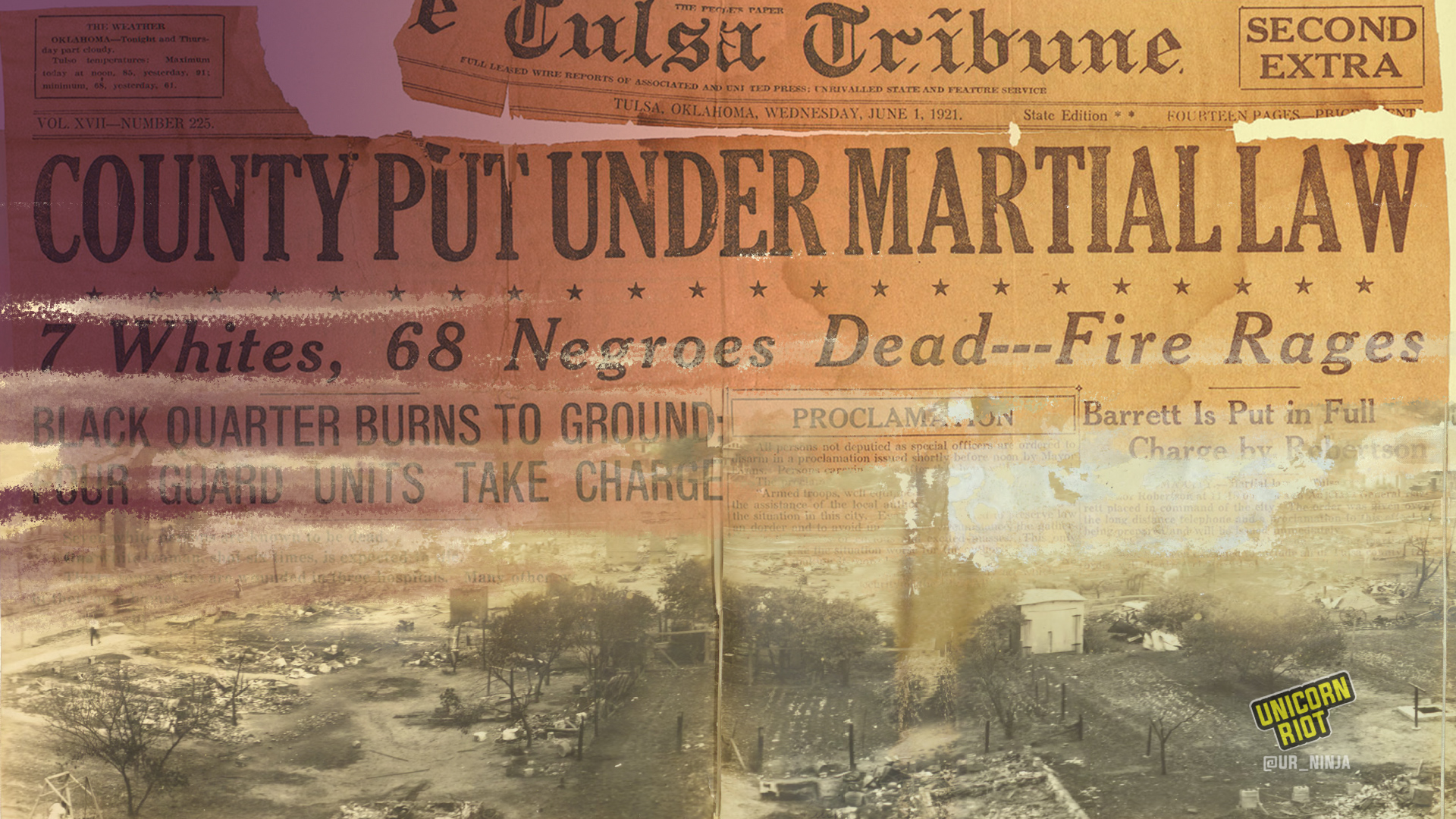

The Dead Are Rising: Understanding the Planned Attack in Tulsa 100 Years Later

Understanding the initial incident in Tulsa and the events that precipitated it are critical to truly understanding what took place 100 years ago. Calculated white men organized a mob of up to 10,000, deputized by local law enforcement, and massacred the prosperous Black Greenwood community, all based on a lie.

Today the world knows the story of the Black 19-year-old Dick Rowland, accused of assaulting white 17-year-old Sarah Page. Following news of Rowland’s arrest, a white lynch mob came for Rowland and were met by an armed group of Black World War I veterans at the courthouse. From there battles took place and the massacre ensued, destroying Greenwood, also known as Black Wall Street, so the story goes.

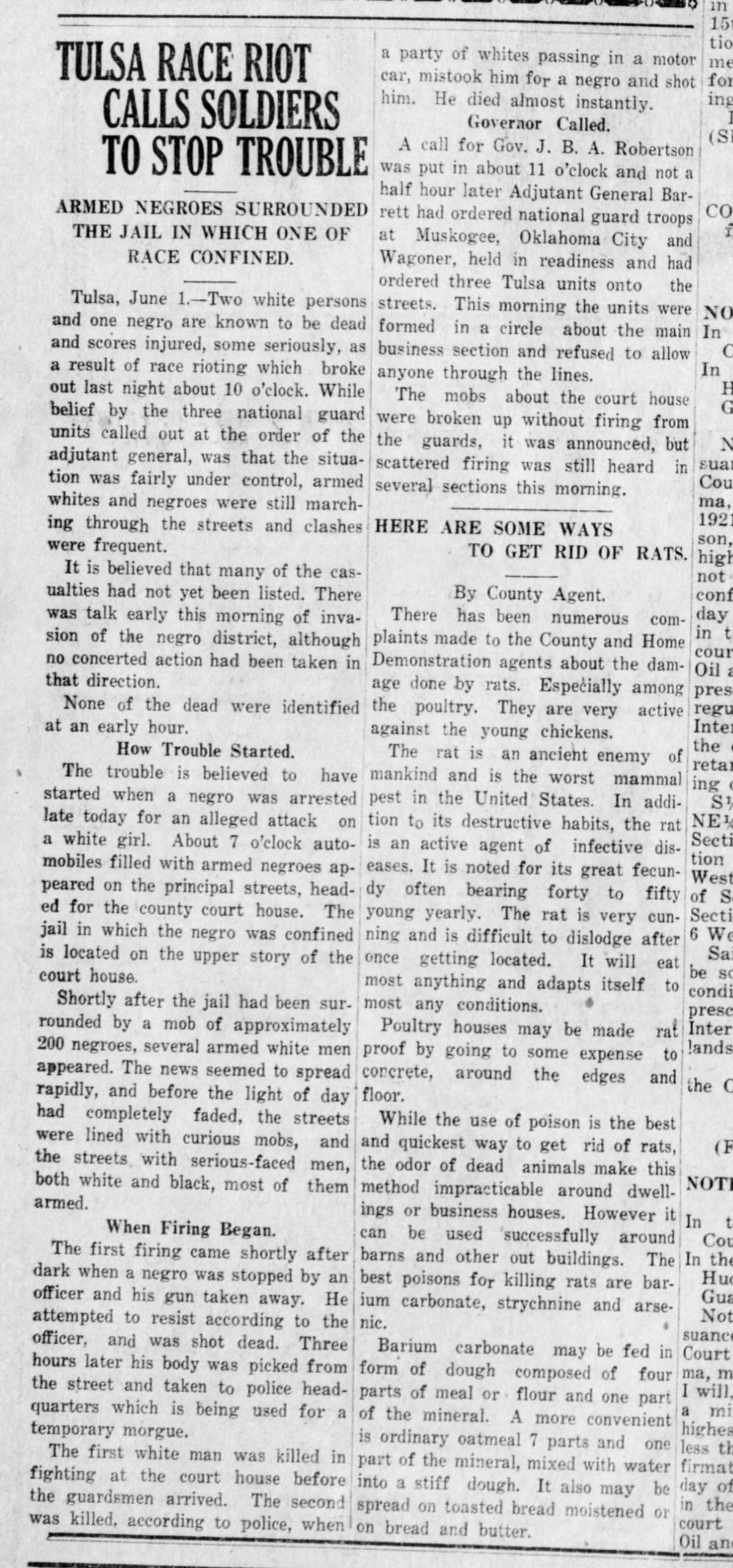

“The first firing came shortly after dark when a negro was stopped by an officer and his gun taken away. He attempted to resist according to the officer, and was shot dead.”

– The McCurtain Gazette, June 1, 1921

White newspapers blamed armed Black men for starting the violence, including local newspaper The McCurtain Gazette, which noted on June 1, 1921, “The first firing came shortly after dark when a negro was stopped by an officer and his gun taken away. He attempted to resist according to the officer, and was shot dead. Three hours later his body was picked up from the street and taken to police headquarters which was being used for a temporary morgue.“

“The first white man was killed in fighting at the courthouse before the guardsmen arrived. The second was killed, according to police, when a party of whites was passing by in a motor car, mistook him for a negro, and shot him,” claimed the Gazette.

Labor Disputes

In the summer of 1921, America was raging with labor strikes including clothing workers who were just ending a nationwide strike when the massacre took place. Stonecutters in Oklahoma were on strike at the time and railroad workers nationwide were being hit with massive cuts in wages, upwards of 15%, and on the verge of striking.

Understanding post-World War I labor struggles in the U.S. is necessary to fully comprehend the race massacre in Tulsa. There were consistent labor shortages on plantations following the civil war. After the end of WWI, white and Black men returning home from overseas competed for jobs. White labor agitation led to racial violence against Black people around the country, with the ‘red summer’ of 1919 being the most infamous. (‘Red’ referred the blood of Black people flowing in the streets.)

“Three hours later his body was picked up from the street and taken to police headquarters which was being used for a temporary morgue.”

– The McCurtain Gazette, June 1, 1921

Segregated Tulsa

Despite brutal segregation throughout the Jim Crow south, there were always still interracial relationships, ranging from the intimate, to the platonic, to strictly business. Blacks and whites were interdependent on one another in their daily lives, according to Keith Mayes, associate professor of African-American and African Studies at the University of Minnesota.

And yet, Tulsa was notorious for racial segregation. It was the only city in America that boasted of separate telephone booths.

Tulsa was two different cities: one for Black people and one for whites.

“There is complete separation of the races so that a colored town is within the white town.”

– W.E.B. Dubois

It is nonsensical to believe Dick Rowland, in between shining the shoes of white segregationists, boldly defied Jim Crow laws on his bathroom break by assaulting a white girl at her place of employment.

On May 31, 1921, the Tulsa Tribune published the front-page headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator,” and an afternoon edition “To Lynch Negro Tonight!,” which inflamed racist white residents. Walter White investigated the incident for the NAACP and wondered why people were willing to believe that Rowland was foolish enough to attack a white girl on an elevator on a holiday during a time of terror, according to the National Endowment for the Humanities.

It is more logical to believe that Rowland and Page knew each other prior to that dreadful Memorial Day and likely had regular encounters.

Defying Jim Crow

Not only did Rowland and Page know each other before he stepped on the elevator, but they were in love and were planning to defy Oklahoma’s Jim Crow law banning interracial marriage, according to Ellouise Cochrane-Price, the daughter of massacre survivor Clarence Rowland and a cousin of Dick Rowland. Cochrane-Price recently told an audience at the Oklahoma Black Caucus gala that the two “were planning on getting married. They had spent many Sundays over my grandma’s house, at family dinners.”

Lead investigative journalist of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, Deneen Brown, recently discovered that it was Page who freed Rowland: “[T]he charges were eventually dropped and Page later wrote a letter exonerating him…”

It’s likely Page’s employer found out about this relationship and fabricated the assault.

We may never know who really initiated Rowland’s setup, but whoever they were. they used it as the pretext to carry out the massacre at Greenwood, meaning it was almost certainly a planned attack.

“Our country’s national crime is lynching. It is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob.”

– Ida B. Wells

Public-Private Corruption

The 2001 report published by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 did not unanimously conclude that the attack was planned, but they included this in their findings: “At the time, many said that this was no spontaneous eruption of the rabble; it was planned and executed by the elite. Quite a few people — including some members of this commission — have since studied the question and are persuaded that this is so, that the Tulsa race riot was the result of a conspiracy.”

Nepotism, often in the form of “good ole boy” networks, was commonly practiced in Tulsa and throughout the Jim Crow South. The study quoted one massacre survivor saying: “There were a lot of big shot rednecks at that courthouse who ran the city and still do” (pg. vii of the 2001 Oklahoma Commission report).

The overarching corruption between local government and the private sector in 1921 Tulsa is clear from a cursory glance at archived records from that time.

Comments by Tulsa police chief John Gustafson about allowing the lynching of Roy Belton (a white man) to take place nine months before the Tulsa Race Massacre made clear that local law enforcement not only were uninterested in protecting Blacks, but they were in cahoots with white lynch mobs: “Any demonstration from an officer would have started gunplay and dozens of innocent people would have been killed and injured.” (p. 52 of the 2001 report)

In the days that followed, the chief applauded the lynching, saying: “‘[I]t is my honest opinion that the lynching of Roy Belton will prove of real benefit to Tulsa and the vicinity. It was an object lesson to the hijackers and auto thieves.” (p. 52 of the 2001 Oklahoma Commission report).

Slavery by Another Name

The most flagrant form of public-private corruption in 1921 was the peonage system: a debt system, implemented by local authorities and plantation owners, designed to re-enslave Black men.

“Jim Crow laws also known as “black codes” allowed police to arrest young Black men for vagrancy, loitering, lurking and curfew,” according to Mayes. Being Black and unemployed was essentially criminalized, and once such a person was convicted by a county judge, local law enforcement, usually the county sheriff, would sell the prisoners’ bond to local plantations where these men were put back into slavery.

In many ways the peonage system was worse than chattel slavery because plantation owners had no incentive to take care of their workers. They were disposable, with a steady supply of prisoners to replace them, according to Mayes.

The trial for the massacre of 11 Black men held captive at the John S Williams plantation in Georgia was taking place during the Tulsa Race Massacre. Oklahoma farmers engaged in the same peonage system.

A day after the fighting in Greenwood ended, “Farmers rounded up negroes and took them to the detention centers,” wrote the Oakland Tribune on June 2, 1921.

A collection of contemporary newspaper clippings (PDF collected by Unicorn Riot, 20 pages – zoom in for high-resolution scans)

Truth Bombs

Although several survivors of the Tulsa massacre said they witnessed planes above shooting and dropping bombs, local newspapers scrubbed these accounts from the public record. A 1921 American Red Cross report added, “Eye witnesses also claim that many houses were set afire from aeroplanes” (p. 7). The two Black newspapers in Greenwood themselves were bombed, according to the findings published in the 2001 report (p. vii).

A railroad porter who witnessed some of the 1921 air assault on Greenwood was quoted in the 2001 report: “We reached Tulsa about 2 o’clock.“

“Airplanes were circling all over Greenwood.

We stopped our cars north of the Katy depot, going towards Sand Springs. The heavens were lightened up as plain as day from the many fires over the Negro section.

I could see from my car window that two airplanes were doing most of the work.

They would every few seconds drop something and every time they did there was a loud explosion and the sky would be filled with flying debris.”

– Survivor Testimony from The Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921

Despite the attempted erasure of the bombing of Greenwood, the Morning Tulsa Daily World, a white newspaper, published an article, “Tulsa Man First to Transport Nitro by Means of an Airplane” on April 20, about six weeks before the massacre. The article declared one D.A. Wilcox to be first man to transport the dangerous nitroglycerin by airplane, stating that a careless movement “may only leave a grease spot.” The irony was also noted in the report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

One survivor recalled “Sinclair Oil Company owned one of the airplanes used to drop fire bombs on people and buildings,” according to the study (p. vii of the 2001 report).

Another survivor, Veneice Dunn, Simms said in a 1999 videotaped interview for the study, “we [heard] planes and knew the fighting was going on; hearing the shootings and things. All you can hear was boom, boom, boom.” (Featured in the PBS documentary: Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten).

On June 1, with Tulsa “race riots” covering papers’ front pages, there was an ambiguous article tucked away on page five in the Oklahoma City Times headlined: “Bomb Explosion Toll Fixed at Five.”

More research confirms that 1200 miles away, the U.S. was playing “war games” at the exact moment when Tulsa was bombed. The army was performing a drill and accidentally exploded a bomb, killing 5 soldiers at a military base in Aberdeen, Maryland.

The New York Times said of the accidental explosion in Aberdeen: “The tragedy casts a damper on the enthusiasm of the officers…at the camp, where extensive preparations had been made for the coming contest between air and sea armaments of the nation.”

Causation

The feds placed unwavering blame on local authorities for the massacre at Greenwood. According to the Oklahoma City Times on June 2, 1921, National Guard commander of state troops in Tulsa, Adjutant General Barret was “emphatic in charging that a complete fall down of the local peace officers was responsible for the riot and said that the factors which led to it were an “impudent negro, a hysterical girl and a yellow reporter.”

“Men holding special permits to carry weapons were chiefly instrumental in inciting the outbreak and did most of the shooting,” Barret said of the thousands of deputized white men who made up the mob.

The New York Times wrote on June 3:

“The Tulsa race riot has been described as the worst outbreak of its kind in the history of the country.

… The cause must lie deeper. Friction between the whites and the negroes has been growing in Oklahoma. It is not altogether racial; in part it is economic. … The savage outbursts in Tulsa leaves no room for doubt that the rough element among the whites was ripe for a rising to teach the negroes their place.”

Early civil rights giant W.E.B. Du Bois, co-founder of the NAACP and editor of its newspaper, The Crisis, plainly tied the massacre to an economic war between white and Black Tulsans. Accusations against Dick Rowland were merely a pretext to escalate into full blown war, Du Bois wrote:

“I have never seen a colored community so highly organized as that of Tulsa. There is complete separation of the races so that a colored town is within the white town. I noticed a block of stores built by white men for negro business. They had long been empty, boycotted by the negroes.

“The colored people of Tulsa have accumulated property, have established stores and business organizations and have also made money in oil. They feel their independent position and have boasted that in their community there have been no cases of lynching. With such a state of affairs it took only a spark to start a dangerous fire.”

W.E.B. Du Bois

It was noted by several publications that the white mobs first robbed and looted Black businesses before setting them ablaze.

Ida B, Wells, also an early civil rights fighter and co-founder of the NAACP, said lynchings were never about protecting white women: “This what opened my eyes to what lynching really was: An excuse to get rid of negroes who were acquiring wealth and property. And thus keep the race terrorized and ‘keep the niggers down.’”

In the aftermath of the massacre, on June 14, 1921, at the meeting of the Tulsa City Commission, the words by Mayor T.D. Evans are notable: “[T]his uprising was inevitable. If that be true and this judgment had come upon us, then I say it was good generalship to let the destruction come to that section where the trouble was hatched up, put in motion and where it had its inception. All regret the wrongs that fell upon the innocent Negroes and they should receive such help as we can give them. It…is true of any warfare that the fortunes of war fall upon the innocent along with the guilty. This is true on any conflict, invasion, or uprising…” (p. 178 of the 2001 report).

Historian Karlos K. Hill recently remarked: “The Negro Wall Street wasn’t just a prosperous Black community. It was a symbol for what was economically possible for Black people in Jim Crow America.”

Reports of Arson Plots

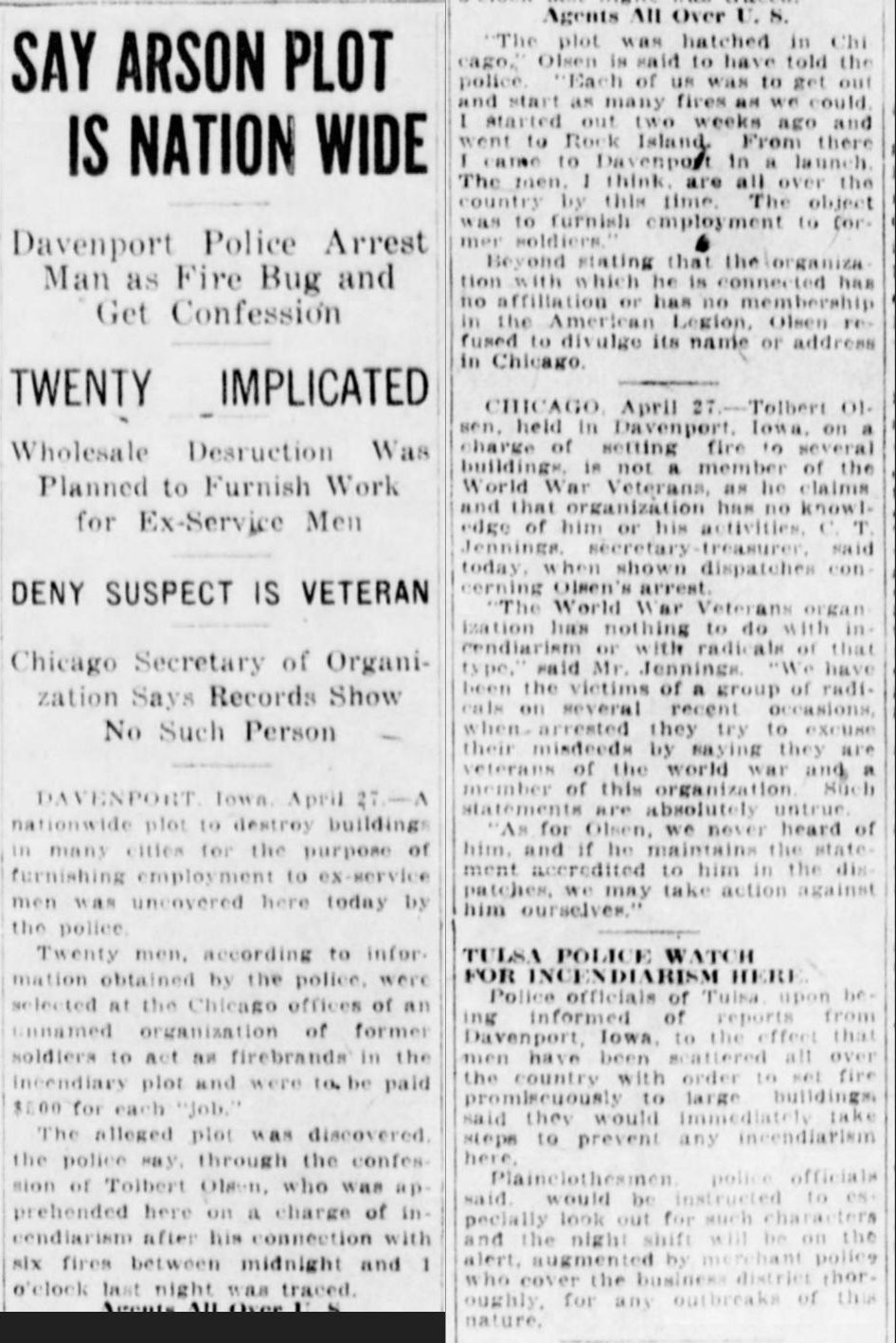

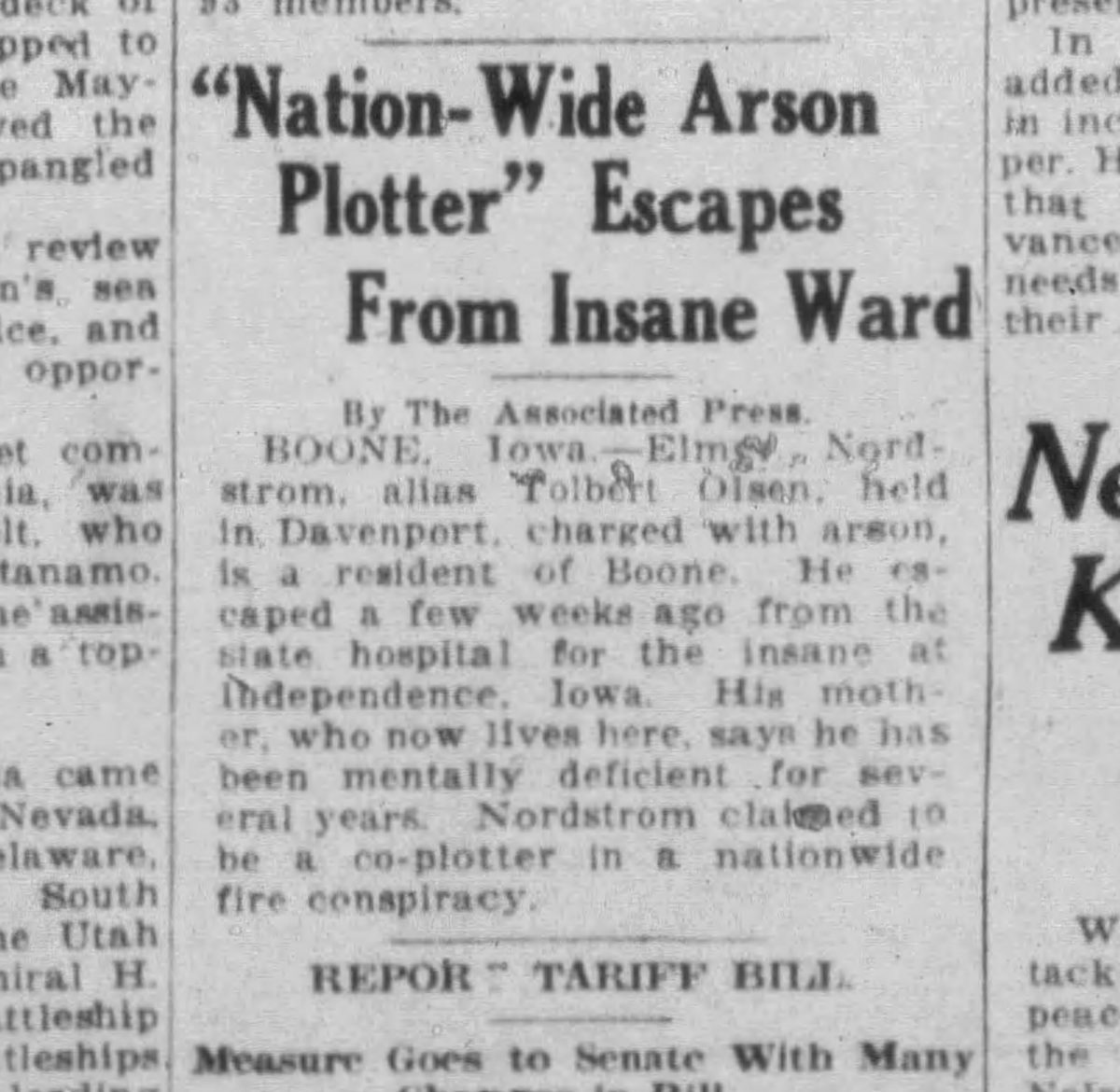

There is more evidence suggesting the massacre could have been a more calculated attack, rather than a spontaneous riot.

Research unearthed a 1921 nationwide arsonist plot, perhaps connected to the American Legion, designed to create jobs for white veterans. On April 28, just one month before the Tulsa Race Massacre, the the Morning Tulsa Daily World reported:

“A nationwide plot to destroy buildings in many cities for the purpose of furnishing employment to ex-service men was uncovered today by police.

… [F]ormer soldiers [were] to act as firebrands in the incendiary plot and were to be paid $7.00 for each job.”

– The Tulsa Morning Daily, April 28, 1921

Tulsa police along with police around the country were on high alert.

Furthermore, Tulsa county agents published this in the McCurtain Gazette on June 1, the day the bombing began, making explicit white desires to exterminate the Black population by comparing them to rats:

“There has been numerous complaints made to the County…about the damage done by rats. Especially among the poultry. They are very active against the young chickens.

The rat is an ancient enemy of mankind and the worst mammal pest in the United States. In addition to destructive habits, the rat is an active agent of infective diseases. It is noted for its great fecundity often bearing forty to fifty young yearly.”

– The McCurtain Gazette, June 1, 1921

Recalibrating the Narrative

Paul Spies, professor of urban education at Metropolitan State University said, “Black Wall Street wasn’t Reconstruction, it was construction. The same terrorism the KKK reigned down in the south to squash Reconstruction and force Jim Crow, happened on a mass scale in Tulsa. And that wasn’t successful without deep collaboration from different entities.”

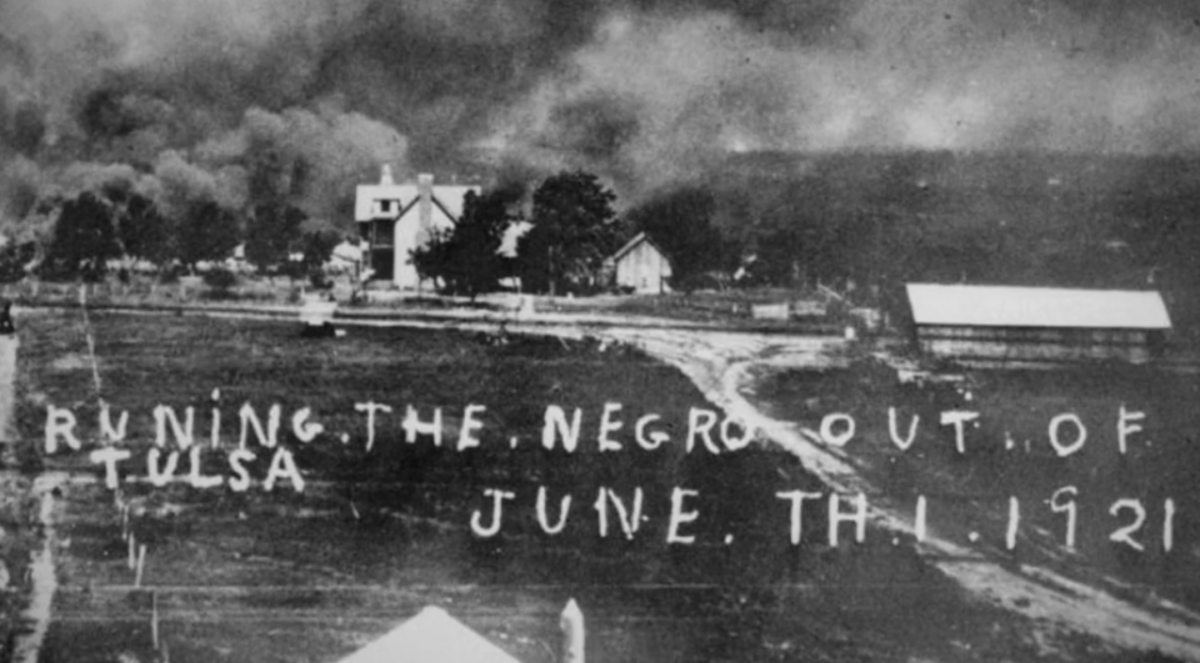

According to human rights investigator Eric Stover, the Tulsa Race Massacre was state-sanctioned when law enforcement deputized upwards of ten thousand white men who participated in the events. Approximately 300 Black Tulsans were massacred, according to the Red Cross. Thousands of Black Tulsans were made homeless and sent to internment camps.

“When we got to the convention hall, they searched us before they let us go in,” survivor Eunice Jackson said in a 1999 interview. Authorities took her mother’s revolver she had kept for protection before letting the family inside. Jackson noted how they already had the ID cards for the Black refugees when they arrived.

The Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 offered this: “For some, what occurred in Tulsa on May 31 and June 1, 1921 was a massacre, a pogrom, or, to use a more modern term, an ethnic cleansing. For others, it was nothing short of a race war. But whatever term is used, one thing is certain: when it was all over, Tulsa’s African American district had been turned into a scorched wasteland of vacant lots, crumbling storefronts, burned churches, and blackened, leafless trees,” (p. 24).

Tulsa was not a “race riot” according to Spies. “As a white person looking back at what happened 100 years ago, it seems pretty clear to me that what the white folks in Tulsa did was an act of ethnic cleansing. By trying to burn out, and bomb out, and shoot out, and wipe out a whole thriving Black community of more than ten thousand people.”

“Their very existence threatened white people’s belief in white supremacy,” Spies asserted.

Observers must question if white Tulsans knew the truth, that Dick Rowland never attacked Sarah Page: would the masses still have participated in this ethnic cleansing?

Following the “race riot”, Tulsa Police Chief Gustafson was fired and indicted, not for involvement in massacring the Black community, but for dereliction of duty and corruption for connection to a car-theft ring.

Further Resources

- A collection of contemporary newspaper clippings (PDF collected by Unicorn Riot, 20 pages – zoom in for high-resolution scans)

- Red Cross Condensed Report (National Archives)

- Featured document display: Black Wall Street (National Archives Museum)

- Pieces of History: The Tulsa Massacre (National Archives)

- Photo album of the Tulsa Massacre and aftermath (National Archives Catalog)

About the author: Marjaan Sirdar is a freelance writer and the host of the People Power Podcast. He dedicates this piece to his ancestors Elijah and Clara Poole, their small children, their parents and siblings, who all boarded a train in April 1923, abandoning Jim Crow Georgia for the factories of Detroit. He is a great-grandchild of Black Power icons, the Honorable Elijah and Clara Muhammad of the Nation of Islam.

Cover image composition by Dan Feidt.