Icebreaker Pt 6 – Leaked ICE Special Response Team Handbook for Planning and Executing Armed Raids

United States – Unicorn Riot obtained confidential Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE) special agent policy manuals, which were in effect during the agency’s earlier years under presidents Bush and Obama. Icebreaker Part 6 covers ICE’s “Special Response Team” (SRT) area of doctrine, the section of ICE organized along paramilitary lines.

At 40 pages, the SRT handbook, dated November 20, 2005, covers how armed raids should be structured and managed by ICE personnel.

The manual was published just prior to the reorganization within ICE of their Office of Investigations into the new, larger agency of Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), and was official policy for at least 11 years, according to the 2016 version of the Special Agent Handbooks obtained by GovernmentAttic.org.

Last week, the ICE SRT program got increased attention when the agency posted a notice that it is ratcheting up its training program with the purchase of “Hyper-Realistic™” raid simulation materials from Strategic Operations, a military contractor based in San Diego, California. (Strategic Operations has built similar immersive training sets for the U.S. military.

ICE did not adequately redact the delivery order approval notice, failing to conceal that the new training gear will be set up at the politically-sensitive site of Fort Benning, Georgia. The U.S. Army base is the home of the U.S. counterinsurgency and torture training center formerly known as the School of the Americas, which opposition groups like School of the Americas Watch have been trying to get shut down for decades.

Civil liberties expert Kade Crockford pointed out this is “some real boomerang theory in action. For decades the security state hosts a school for foreign services to teach how to violently quash left resistance” before expanding the same site into domestic training operations. The new ICE SRT training requisition includes “Arizona” and “Chicago” sets.

Related problems have surfaced inside ICE since the last release in this series, Icebreaker Pt. 5 – Confidential Homeland Security Undercover Operations Handbook last June.

#Icebreaker Series - Unicorn Riot series on ICE policy manuals

- Icebreaker Pt 1 – Secret Homeland Security ICE/HSI Manual for Stripping US Citizenship (Feb. 14, 2018)

- Icebreaker Pt 2 – Confidential Homeland Security Asset Forfeiture and Search and Seizure Handbooks (Feb. 22, 2018)

- Icebreaker Pt 3 – Confidential Homeland Security Fugitive and Compliance Enforcement Handbooks (Feb. 28, 2018)

- Icebreaker Pt 4 – Homeland Security Special Agent On-the-Job Training Manual (Apr. 27, 2018)

- Icebreaker Pt 5 – Confidential Homeland Security Undercover Operations Handbook (Jun. 22, 2018)

- Icebreaker Pt 6 – Leaked ICE Special Response Team Handbook for Planning and Executing Armed Raids (Sept. 18, 2019)

- Icebreaker Pt 7 - ICE Case Management Handbook Based on Federal Law Enforcement "System of Systems” (Dec. 13, 2019)

- Icebreaker Pt 8 – Leaked ICE Handbooks for T and U Visa Application Investigations (Dec. 18, 2019)

- Icebreaker Pt 9 – Leaked Interrogation and Arrest ICE Manuals (Jan. 1, 2020)

- Icebreaker Pt 10 – Leaked ICE Agent Private Bill and Commercial Trade Fraud Investigation Handbooks (Jan. 4, 2020)

- Icebreaker Pt 11 – Bush/Clinton Era Customs Investigators Manuals (Feb. 13, 2020)

ICE agency’s organizational problems, raids linked to pattern of increasing federal tactical team activity

ICE in 2019 consists of two wings: Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) and Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO). ICE and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) were both created in 2003 as an outcome of the U.S. 9/11 Commission recommendations and the early phase of the “War on Terror.”

ERO is the wing of ICE completely focused on locating, detaining, and often deporting immigrants for civil immigration violations. The platform of HSI, while often involved in supporting ERO, focuses on “the full homeland security enterprise“, including counter-terrorism operations.

HSI formed from parts of several agencies, including the U.S. Customs Service (USCS) Office of Investigations. It is the largest investigative body inside the Department of Homeland Security, second in staff numbers only to the FBI.

According to a 2015 Congressional Research Service (CRS) paper by crime policy analyst Nathan James, ICE had 25 federal tactical Special Response Teams (SRTs) in 2014, 17 of which were assigned to HSI. ICE’s Special Response Teams are the corollary to the FBI’s Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) Teams. Both are considered “Police Paramilitary Units” (PPUs) in academic literature.

As with SWAT teams, the most visible sign of ICE’s Special Response Teams is their huge armored tactical vehicles which can provide cover from firearms. Trucks are typically marked with “SAC“, meaning Special Agent in Charge, as well as a code indicating the field office. HSI is geographically divided into 26 SAC field offices in major cities around the United States.

In June 2018, serious concerns were raised by field directors from 19 HSI SAC field offices about non-transparent, inefficient and ineffective alignment of DHS’s “law enforcement assets“. The 19 ICE-HSI special agents in charge (SACs) called for splitting HSI off from ICE to form “two separate, independent entities“. The field directors agreed that the two sub-agencies within ICE had become so separate and specialized that the work of the government agency “can only be described as a combination of the two distinct missions (i.e., ‘Enforcement/Removal and Transnational Investigations’).”

In addition to the issue with ICE-HSI’s dual missions, there is tension in the labor force of ICE agents. Whereas ERO officers make up a bargaining workforce with more control over their work shifts and whom receive extra pay for “Administratively Uncontrollable Overtime” (AUO), HSI officers are subject to callouts at any hour and must make do with standard Law Enforcement Availability Pay (LEAP).

“This difference in bargaining status, the policies that govern union and nonunion-based operations, and the occupational specialization and training, makes it difficult for ERO and HSI staff to supplement each other if needed.” – letter (PDF) from SACs

The letter cites HSI’s difficulties with relationship-building due to both HSI’s large role in domestic operations such as the Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTFs), as well as the massive controversies around ERO-led practices. It read,

“Considering [Executive Order] 13773 and the fact that we believe ICE has reached a point of final maturation in its continued evolution, we propose to restructure ICE into the two separate, independent entities of HSI and ERO.”

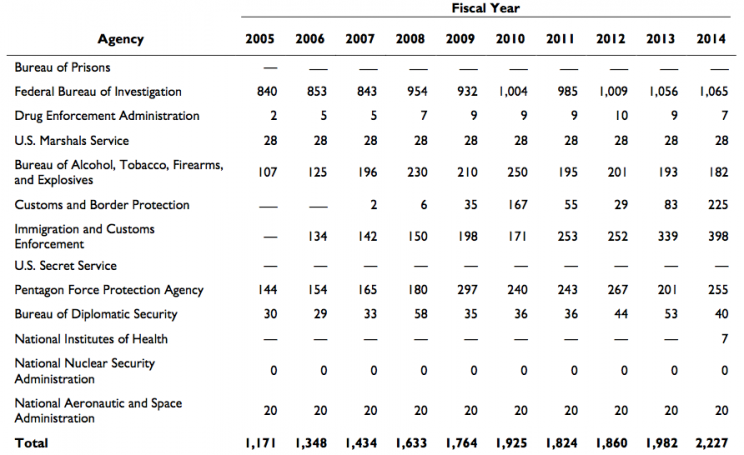

Federal tactical teams’ deployments have steadily increased over the 2005-2014 period examined by congressional researchers. In 2014, ICE deployed its Special Response Teams nearly 400 times, compared to 134 in 2006.

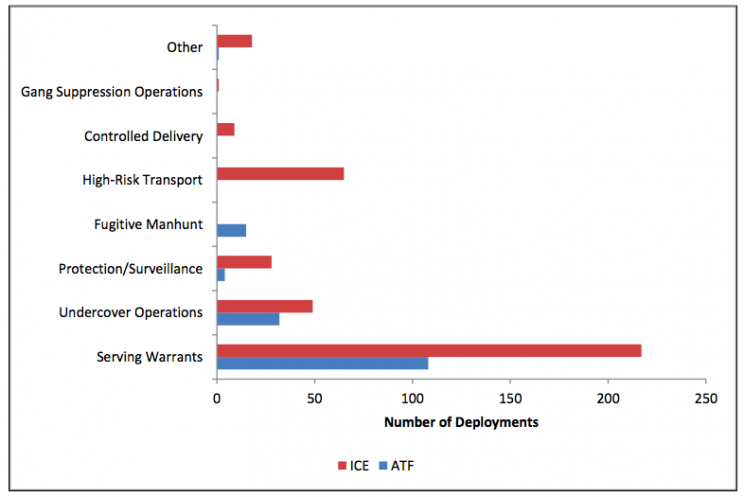

Data found in 2015 by the analyst in crime policy showed that more than four out of five times SRTs were “serving warrants, supporting undercover operations, and conducting high-risk transports” suggesting that federal tactical teams such as ICE’s SRTs

“… are being “normalized” in regular law enforcement operations. That is to say, they are being used for operations beyond those for which PPUs were originally established: responding to active shooters, barricaded suspects, or hostage situations.” – Nathan James, CRS crime policy analyst, 2015 (PDF)

The operating conditions of Special Response Teams are a critical component of union negotiations with the Department of Homeland Security. In 2009, a leaked union negotiation document, republished by PublicIntelligence.net, showed a number of pertinent details about how ICE SRT teams are organized.

Questions have been raised recently about whether employers have called in ICE enforcement to help union-bust during periods of labor organizing, particularly in the context of a large set of ICE raids this summer, some at plants organized by United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW).

The National Immigration Law Center published a partially redacted “Guidance on Civil Inspections of the Employment Eligibility Verification Form (Form I-9) During Labor Disputes” in 2016, which claims that any ICE/HSI investigation will be ‘de-conflicted’ with labor investigations in other federal agencies. This memo was signed by Peter T. Edge, Executive Associate Director, Homeland Security Investigations, another indicator of how closely HSI has become enmeshed in immigration investigations.

Leaked Special Response Team Handbook details how ICE plans armed raids

The entire handbook is embedded below:

hsi-special-response-team-finalPlanning conditions for running paramilitary law enforcement raids, with broad catch-all conditions, are included in HSI’s SRT internal handbook. Any hypothetical claims of increased risk could meet the planning threshold for sending in a SWAT-team style raid.

This kind of planning can result in paramilitary-style over-policing, increasingly used for “civil disturbance” control in US cities.

Previous Unicorn Riot coverage of state level “Mobile Field Force” and other special police operations and doctrine:

- Minnesota Police Train at Military Base as Line 3 Pipeline Protests Escalate, October 25, 2018

- Multi-Agency Task Force Prepares “Rules of Engagement” For Line 3 Protests, February 11, 2019

- Trump’s FEMA to Train Local Police for “Field Force” Crackdowns, November 16, 2016

“The SWAT unit and its military tactics were born a year after [Chief William] Parker left, in 1967, as a reaction to the Watts riots of 1965,” according to Dennis Romero in LA Weekly. (More about Watts here [1] and [2]).

The 2015 CRS report references a 2014 publication by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) on the excessive militarization of police forces in the U.S., as well as a 1997 scholarly work on the debate over police militarization:

“Some will see the rise and normalization of PPUs as a necessary and rational approach to today’s crime, gang, and drug problems; others will view it as bureaucracy building and as evidence of a government in crisis moving towards a police state.” – Peter B. Kraska and Louis J. Cubellis, ‘Militarizing Mayberry and Beyond: Making Sense of American Paramilitary Policing’

The Special Response Team Handbook consists of 40 pages including a cover, with seven chapters and six appendices. (Page numbers indicated here refer to PDF pagination, not the numbers on page footers.)

p2: The cover letter stamped November 28, 2005, from agency director Marcy Forman, says that there were eight SRT teams throughout the United States. This policy document provides “national direction” including “the team’s formulation, training, certification and establishment“.

p3: Foreword: This provides a “single source of national policies, procedures, responsibilities, guidelines and controls“.

CHAPTER 1 – OVERVIEW

p6: Each SRT is trained to conduct high-risk enforcement operations and must have at least 12 ICE trained, certified and active team members. Its policies are governed by the DHS Use of Deadly Force Policy (July 1, 2004), the Interim ICE Firearms Policy (July 7, 2004) and the Interim ICE Use of Force Policy (July 7, 2004).

“High risk” activities include fortified buildings, suspects with a ‘history of violence or resisting arrest‘ or ‘are members of organizations which advocate violence‘, as well as anything ‘above average risk‘ or a ‘disturbance in an ICE facility that poses a risk of physical injury to government employees, detainees or others.‘

Risk assessments for the need of having SRTs must be completed every three years by each SAC.

CHAPTER 2 – ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

p7: The ICE Deputy Assistant Secretary designates the National Firearms and Tactical Training Unit (NFTTU) to provide oversight and support for the national SRT program including reviews and certifications, and acquiring and testing specialized weapons and ordinance.

The ICE National Tactical Coordinator (NTC) is the agency-wide point of contact for local program managers and responsible to the Deputy Assistant Secretary. They consult on operations, prepare reports and control training curriculum, accreditation, and national training exercises.

p8: SRT Office of Investigations National Program Manager (NPM)

This officer is supposed to review this handbook every three years and maintain liaison with external law enforcement agencies, as well as review ‘sensitive circumstance SRT operational plans’, and create after-action reports following each tactical enforcement action.

p9: Special Agent in Charge

The SAC is responsible for “all SRT operational and administrative functions“, and all SRTs are under their immediate control. This includes approving operations and team selection, reviewing operational plans, and annual management reviews.

p10: Tactical Supervisors

Must be a supervisory special agent trained in the ICE SRT Basic Course delivered by the NFTTU. They will exercise command and control at all times through the Team Leaders during deployed operations, but only the SAC can actually deploy the teams.

The supervisors’ duties include briefing the SAC on status and readiness, coordinating objectives with case agents, ensure that search and arrest warrants are valid and that addresses match, and keeping files on each SRT deployment, managing training and equipment, and liaison both inside and outside of ICE with their Tactical Supervisors.

Local Training Coordinator

The LTC creates the local training programs and should be one of the most knowledgeable and experienced members.

p11: Team Leader

The Team Leader is responsible for preparing written, detailed operational plans. The case agents assist team leaders by providing all the information for the risk analysis. Team leaders submit operation plans through the tactical leader for approval. They also supervise unit members and assign tasks during planning and deployment, and know the status of all team members, suspects and weapons at the end of operations, and preparing after-action reports. They also provide ‘diversionary devices‘ (flashbang grenade type devices) before operations and collect any spent ones.

p12: Team Members. SRT team members are armed ICE officers approved by the SAC to join the teams. They must pass firearms and physical skills tests, and 8 hours of training a month.

CHAPTER 3 – SELECTION, TRAINING, AND STANDARDS

p12: SRTs are volunteers only and will not form if there are not 12 volunteers available at the SAC office. The criteria are “enforcement, experience, sound judgment, professionalism, discipline, compatibility, physical fitness, and firearms proficiency.”

Only training via the NFTTU is considered acceptable. Trainees may be admitted to training before they have full certification but cannot deploy with the team on operations.

Failing to meet physical skills and/or firearms standards and missing more than two training sessions in a row triggers inactive status, and are not allowed to go on high-risk enforcement actions.

The physical skills test is given annually and includes 20 push-ups in 1 minute wearing tactical gear, “III-A body armor, battle dress uniform (BDU), helmet, boots, and web gear with handgun“; vaulting over a 6 foot wall in tactical gear; a 1.5 mile run in 12 minutes without gear; and dragging 150 pound object 25 yards in 25 seconds.

CHAPTER 5 – DIVERSIONARY DEVICES

p18: Commonly known as flash-bang grenades, an extended policy on their use and management. These are small explosives (USDOT Class D “Detonating Fuzes”) that can daze or injure targets. Their use and possession is limited to trained SRT members and NFTTU personnel.

p19: “Diversionary devices utilized by the SRT shall only be deployed during the execution of search or arrest warrants, arrests without a warrant, other sanctioned SRT missions, or organized SRT training. Expended diversionary device hulls should be recovered and preserved as evidence when used in other than training situations…. The NFTTU shall be responsible for coordinating the testing and selection of all authorized diversionary devices used by SRTs.”

p21: Any use of these devices needs to be logged to through the NPM to the NTC within 72 hours of use.

CHAPTER 6 – GUIDELINES FOR THE USE OF AN SRT

p22: “All team operations will be planned in accordance with procedures taught by the NFTTU. Operational plans must include a “Risk Analysis for Tactical Operations” (see Appendix B) and a “Pre-Entry Planning Worksheet for Tactical Operations” (see Appendix C).”

p22: The Tactical Supervisor gets requests from ICE offices to deploy SRT teams.

p22-23:

“Sensitive circumstances” include politically unique conditions such as “An investigation of possible corruption or other criminal conduct by any elected or appointed official, or political candidate for a judicial, legislative, management, or executive level position of trust in a Federal, state, or local government entity or political subdivision thereof; An investigation of possible corruption or other criminal conduct by any foreign official or government, religious organization, political organization, celebrities, or the news media; and An investigation of any activity having a significant effect on, or constituting a significant intrusion into, the legitimate operation of a Federal, state, or local government entity.“

p23: In “Request Under Exigent Sensitive Circumstances” some of the steps can be skipped in “instances when an immediate activation of the SRT is necessary to ensure officer or public safety in the opinion of the Tactical Supervisor or SAC.”

p24: Chemical agents policy is similar to the national FEMA “Field Force Operations” doctrine first reported on by Unicorn Riot.

“The use of chemical agents must conform to the guidelines established in the Interim ICE Firearms Policy and Interim ICE Use of Force Policy, to include 12-gauge, flameless pyrotechnic ortho-chloro-benzal malonitrile (CS) devices and non-burning air discharge canisters of CS and oleoresin capsicum (OC). If an SRT is deployed in support of mobile field force/crowd control operations, then the use of pyrotechnic chemical munitions would also be authorized.“

Chemical agent treatment training is managed through NFTTU.

p24: “All less-lethal options and specialty impact munitions employed must be in compliance with the Interim ICE Firearms Policy and Interim ICE Use of Force Policy and all other appropriate directives and handbooks.”

p25: prohibited SRT uses: “The SRT will not be used for routine warrant service or other enforcement activities that do not meet the criteria established in this Handbook. The SRT will not be deployed in support of state or local cases outside the jurisdiction or official interest of ICE unless otherwise approved by the Director, OI.” [today the director of ICE HSI]

APPENDIX A – Risk Assessment Memorandum For Establishing and Maintaining Special Response Teams

p27: The criteria of whether or not to have a SRT set up in an a SAC. Two key criteria: “Other enforcement activities whose totality of circumstances presented a greater than normal risk” and “Arrests of suspects who were members of organizations which advocate violence.”

APPENDIX B – Risk Analysis for Tactical Operations

p29: A checklist of information sources to consult before a raid:

“Information Sources Check List with Dates Checked:

a. Utilities;

b. Driver’s license;

c. ICE Information Systems (TECS-II, NAILS, etc.);

d. National law enforcement database systems (NCIC, NLETS, etc.);

e. Other Federal law enforcement database systems (NADDIS, FBI, etc.);

f. Other DHS database systems;

g. Property records;

h. State and local law enforcement sources and database systems;

i. Coordination with any local deconfliction process; and

j. Other relevant information for risk assessment.”

TECS-II case management was covered in Unicorn Riot’s Icebreaker Pt 3: Confidential Homeland Security Fugitive and Compliance Enforcement Handbooks.

TECS-II is also referenced in the recently leaked Palantir data tracking purchase order, which had failed redactions (PDF redactions removed here by Unicorn Riot). Palantir’s Gotham platform is integrated with TECS-II. More about the Palantir platform here. Note this manual is dated from 2005 and federal law enforcement tracking databases have continued to change.

In this context ‘deconfliction process‘ would mean, similar to military use of the term, consulting other parties to see if they have something else going on that area, person or group.

p30: Other criteria for determining if an SRT team should be deployed:

“d. Mentally Unstable:

1. Legally;

2. Apparent; and/or

3. Other.

e. Military, Police, or Tactical Training

f. Associations:

1. Known criminals;

2. Criminal organizations;

3. Paramilitary;

4. Terrorist;

5. Religious extremist;

6. Separatist; and/or

7. Other.”

p31: The outcome is one of: SRT required, SRT not required, or other courses of action recommended.

APPENDIX C – Pre-Entry Planning Worksheet for Tactical Operations

p33: The types of operations are three:

Search Warrant, Cover / Protection / Undercover Operation, Other.

p34: Law enforcement personnel include both undercover and assisting personnel.

p35: Communications include a. Primary radio channel; Secondary radio channel; Go signal; Abort signal; Command post location. Also in Medical Emergencies, Ambulance on-scene; Tactical Emergency Medical Technician, are considered for planning.

APPENDIX D – Request for the Use of an SRT Under Sensitive Circumstances

p38: (as noted above these type of SRT operations are considered politically sensitive and more officials are notified; however details in this request structure summary are slim.)

APPENDIX E – Diversionary Device Inventory Control Sheet

p39: Form for filling in numbers of ‘flash-bang’ explosive diversionary devices including received and expended.

APPENDIX F – Acronyms

ENDNOTES

In the course of reporting, Unicorn Riot looked into the trademarking of “Hyper-Realistic” and found that the trademark had been rejected in the first attempt by the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The following files were extracted from the trademark.

Strategic Operations also provided military simulation packages.

Additional resource on immersive tactical training:

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: