Families Gather to Demand Justice for Those Killed in Tucson’s Jail

Tucson, AZ – A crowd of about 60 people slowly converged on the empty plaza and parking lots of Pima County Jail Friday night. Bathed in the yellow glow of the streetlights, some gathered in groups and chatted while others hurriedly constructed frames for their custom-made vinyl banners commemorating their family members whose lives were lost in the jail.

“We’re out here trying to get our voices heard, for him especially because he doesn’t have one anymore,” said Vanessa Palacios, whose cousin Pedro Xavier Martinez Palacios, 24, died in the jail in January of this year. “So we’re here for him, speaking for him too. We’re not going to stop until we get answers.”

Fathers lit candles and packs of teens gathered around their phones wearing t-shirts bearing the faces of the dead—a lost tío, a friend or cousin missing from their lives. Young children ran holding hands and taunting a 12-foot tall puppet of the grim reaper. Around its neck hung a sign with the name of Pima County Sheriff Chris Nanos: “Nanos, La Muerte.” The children dared each other to touch it, calling it a “monster.”

Stephanie Madero, whose husband Richard Piña died in the jail in 2018, addressed the crowd on behalf of the No Jail Deaths Coalition, the group organizing the event. She told the story of her husband’s death from what she said was a treatable infection.

“He’d been sick for about three weeks,” Madero explained. “If he’d gotten any kind of medical…he probably could have lived. But they waited. He never got to see medical. He passed out in his room and they found him unconscious. He died two weeks later.”

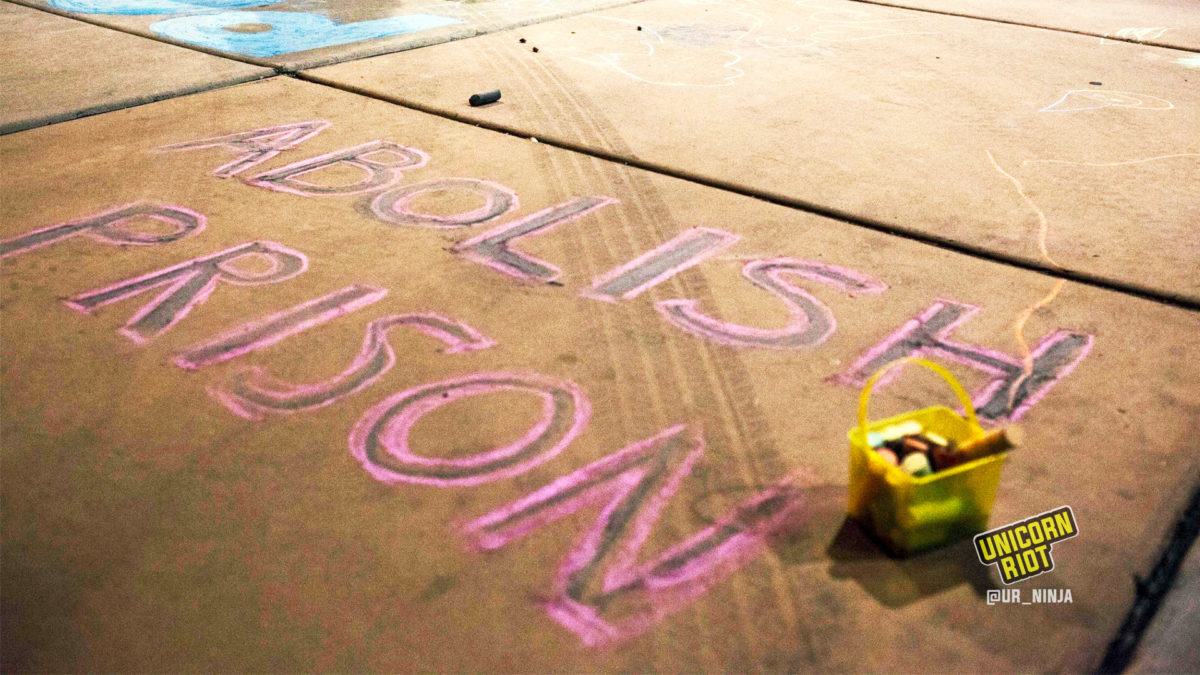

After about an hour of discussion and preparations, a portion of the crowd began to march in circles through the roundabout banging pots and pans while others drew with sidewalk chalk. People banged on street signs with sticks and rocks. Detainees flashed the lights of their cells in silent communion while Lil’ Boosie’s anti-cop anthem blasted from the mobile sound system. Mourners carried prayer candles as they shouted along with the music.

At moments the event seemed less like a protest and more like the funeral processions of six fallen youths that converged in a single place and erupted into a furious, atonal chorus of grief and anger.

A mother walked around the circle, her pace her own, her steps erratic, clutching a large framed portrait of her dead son. As she walked she screamed “fuck the police!” over and over with her voice hoarse, like a mantra or a prayer for redemption. Those around her repeated her screams, but she seemed not to notice.

The No Jail Deaths Coalition was organized late last year as the jail mortality rate turned from anomaly to crisis. A coalition of activists and family members of those who died in the jail, started regularly gathering in front of its razor-wire-topped walls in fall 2021.

That year, ten people lost their lives in the jail and two more died in 2022, as of early May. Last year, the jail’s mortality rate was more than three times the national average with one person dying in its custody every 36 days. Only three of those deaths were attributed to COVID-19. This massive loss of life resulted in little more than words on the part of those in power in Pima County.

No Jail Deaths’ website hosts a memorial page commemorating each person who died in the jail in the last three years.

Liz Casey, a social worker with the Florence Project, represented two clients who died in the jail in 2021—William Omegar, 37, and Jesus Aguilar Figueroa, 70.

“Both of them had been diagnosed previously with mental health issues, some very severe issues like schizophrenia,” said Casey. “William was a refugee who experienced a massive amount of trauma in his life and just never got the culturally competent care he needed to live safely in the community. He was in the jail a lot and also used drugs a lot to cope with the trauma and his mental health.”

Casey now sees her role as advocating for her clients even in death.

“These two individuals specifically don’t really have family around to be able to advocate for them or to let people know that it’s not right for them to die in the jail. I don’t want them to be forgotten or just brushed aside like they didn’t matter. Like their life didn’t matter and their death in the jail didn’t matter.”

Liz Casey

With some exceptions, the roster of jail deaths reads like a chronicle of the city’s most marginalized. Disproportionately Black and Latino, many experienced drug addiction and a huge proportion suffered from serious mental health conditions for which they were not receiving proper support.

“There’s so many people who end up in the jail and have nobody who’s really paying attention to what’s going on with them. To give them legal advice if they get abused in the jail. Really nobody to protect their rights if they’re being violated.”

Liz Casey

The demonstration occurred just a few days before the County Board of Supervisors is set to decide upon a $3.6 million budget increase for the sheriff’s department. Speaking of the proposed budget increase, No Jail Deaths asked in a press release “what good will it serve a dysfunctional at best, and deadly at worst, organization?”

The four most recent deaths at the jail have all been attributed to drug overdoses, according to autopsy reports.

In the face of mounting criticism, Sheriff Nanos announced on March 1 that all jail guards now have access to Narcan, the overdose reversal drug, and will no longer have to wait for medical teams to arrive to respond to an overdose. In contrast, Tucson police announced five and a half years ago that they would begin carrying Narcan.

According to Casey, help for the city’s most desperate simply doesn’t exist at the scale required to meet the need.

“There’s a narrative being pushed in the mainstream by the city that we have very good services and resources—that people can get into housing, that people can get mental health services, that we have a crisis line that we have a homeless outreach unit with TPD who care for people instead of jailing them. And it’s just not true. We’re not significantly different than other cities who have killings by police and in the jails. At this point, we’re probably worse than a lot of cities in terms of death rate by our police and in the jail.”

Liz Casey

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the average mortality rate for all local jails in the United States in 2019 was 167 per 100,000 detainees. In the Pima County Jail, 10 people died in 2021 despite a record low jail population, estimated to be an average of 1,700 detainees per day. That translates to a mortality rate of 588 per 100,000 detainees, or more than three times the national average.

With all the attention the jail is getting, No Jail Deaths’ organizers say people keep approaching them, largely through Facebook, to tell their stories of abuse and misuse of authority on the part of the Pima County Sheriffs and Correctional Officers at the jail.

A 19-year-old man who spoke with Unicorn Riot under conditions of anonymity said that sheriff’s deputies arrested him in March 2022 for little more than walking down the road, booking him into the jail for “refusing to provide truthful name when lawfully detained.” During his arrest, the man said deputies slammed his head into the side of their car, giving him a concussion.

“I didn’t even do anything,” the young man said. “They didn’t read my rights, they just took my wallet out…and put me in the cruiser. It was all like a 30 second process. It was so quick. They put me in that cruiser not even knowing why. They just wanted to mess with me.”

After transporting him to the jail, the man said the deputies put him into a restraint chair because they didn’t like the way he was speaking to them. “I’m all amped up so I’m talking shit,” the man said. “All [of] the sudden I had five sheriffs on me like I’m acting erratic. Freedom of speech is not a crime. I’m not resisting, I’m not being physical, I’m not pushing nobody. I’m doing what you guys are telling me to do, but I’m speaking for myself because it’s wrong what you guys are doing.”

According to the young man, deputies left him in the restraint chair facing the wall for two hours while he screamed for help and asked for water. After an initial court appearance in the morning, he was released.

A search of court records confirmed the time and location of the man’s arrest as well as his charges.

“Jail is for dangerous criminals…” wrote Sheriff Nanos in a 2021 statement on police reform. “By working with our courts, prosecutors, and defense attorneys to find jail alternatives for those serving time in our jail for low level, nonviolent misdemeanors, we not only provide for a safer community, we also save taxpayers millions of dollars.”

As Sheriff Nanos prepares to request millions more taxpayer dollars, family members of those who died in the jail are asking the county not to invest in the future the sheriff has planned.

“3.6 million and he hasn’t even addressed our family members and their deaths or what needs to be done to help stop people from dying in these facilities,” said Madero to those gathered in front of the jail. “That money isn’t going to go to any of them. It’s going to go to staffing, like that guy on the roof over there,” she said, gesturing to the deputies stationed on the roof, observing the crowd.

Under the watchful eye of the sheriff’s department, a motley assortment of people gathered their strength, preparing for the battle ahead.

“We’re going to be in his face as much as we can. We’re not going to give up,” said Madero. “Because our families matter. Our people matter too.”

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: