Hundreds Set to Launch Hunger Strike Inside Stewart Detention Center

Lumpkin, GA — Last weekend, hundreds of people detained at the Stewart Detention Center announced plans for a hunger strike in response to inedible food and inhumane conditions inside the notorious Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility in rural southwest Georgia. Though detainees have continued to eat while they negotiate with the facility’s staff, as many as 800 people are set to refuse food starting this week if their demands are not met.

On the morning of Saturday, Aug. 26, roughly 300 people held inside the Stewart Detention Center were brought out of their holding cells for their morning meal. But when they were presented with the standard meal trays containing “disgusting” food in small quantities, the detainees refused to eat and returned to their cells, Victor Puertas, who’s currently being held at Stewart Detention Center (SDC), told Unicorn Riot.

For two days, detainees refused to eat the food served to them in protest of what current and former detainees have described as inedible meals made with rotten ingredients and served without any fresh produce. But inadequate food is just one issue detainees face inside of the notoriously inhumane detention center, and those planning to strike hope to compel the facility to address their concerns, starting with the food they provide.

After refusing food all weekend, detainees asked to speak with the warden on Monday, Aug. 28, to explain their grievances, according to Puertas, who is among those who refused food last weekend. Though warden Russell Washburn did not meet with the hunger strikers, detainees spoke with an SDC employee and issued their demands, he said.

To start, people inside Stewart are asking the center to honor its menu and serve palatable food in larger portions. Though the facility’s menu boasts dishes such as country stew, jambalaya and vegetable sides, detainees are served starch-based meals with no fruits or vegetables to speak of, Puertas said. Additionally, the portions are too small and the food that’s provided is often moldy.

When the hunger striking detainees spoke with an SDC employee on August 28, they were assured the facility would take steps to address their concerns, Puertas said. Those who refused meals over the weekend opted to continue eating for the rest of the week while waiting to see if SDC makes good on its promise to improve the food.

If the facility doesn’t meet their demands, or show signs of good-faith efforts to improve the conditions detainees are subjected to, as many as 800 people across multiple cell blocks in SDC are set to join in a hunger strike, Puertas said.

While the strike was announced last weekend, tension has been building inside Stewart for weeks.

According to Puertas, tensions boiled over when a group of about 36 people detained at Stewart – a facility known for its lengthy detention periods – were set to be deported. The deportation process, which is a source of relief for many inside SDC, began and the detainees were transferred to an airport. But after being transported, the group was brought back to the center later the same day without explanation, Puertas said.

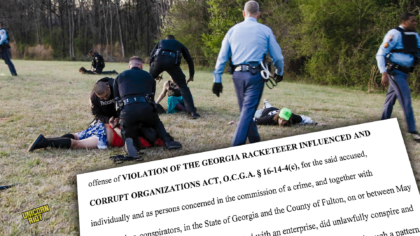

Once back inside Stewart, the detainees refused to return to their cells, leading to a confrontational standoff with center staff and state police. The detainees were ultimately sent to segregation units, and word of the event spread throughout the facility, Puertas said.

The frustration at the failed deportation process added to the already tense atmosphere. Detainees commiserated and shared their frustrations, and roughly three weeks after the confrontation, they decided to take action to push for more dignified treatment.

Advocates, immigration rights organizers and former detainees describe the atmosphere at Stewart as heavy and often hopeless. As a facility, Stewart has a reputation for being something of a dead end for people without immigration cases, Xavier T. da Janon, an attorney who regularly visits detainees in SDC, told Unicorn Riot. As a result, people without cases often spend months locked up without a clear timeline of when they might be released or deported.

“It’s like a no-man’s land,” de Janon said. “If you end up in Stewart, it’s because you’re going to have difficulty getting out.”

Stewart’s long detention periods are compounded by a culture of medical neglect, inadequate staffing practices and inhumane treatment at the hands of a for-profit prison contracting company, Nilson Barahona-Marriaga, a former detainee at SDC, told Unicorn Riot.

Barahona, who was transferred to SDC from the Irwin County Detention Center after participating in a hunger strike there in 2020, described Stewart as a place of despair designed to punish immigrants. Medical neglect, unhealthy meals and language barriers between staff and detainees all add to the heaviness felt inside Stewart, Barahona-Marriaga said.

Stewart is owned and operated by CoreCivic, formerly the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), a multi-billion dollar for-profit prison contractor. It’s not only one of the largest ICE detention facilities in the country, but also among the deadliest. Since 2017, nine people held at Stewart have died – some from medical neglect and COVID-19, others by suicide. Hundreds of inmates have also reported ” a systemic pattern of sexual abuse by detention officers, contractual guards, and ICE employees,” the majority of which aren’t investigated.

Since it’s inception in 2004, public criticism against the facility and calls for its closure have grown, but Stewart County and Georgia state have, so far, resisted these calls mainly on the excuse that it acts as a “essential moneymaker for the area.” Like many prisons across the U.S. the Stewart Detention Center also uses prison labor to turn a profit, where detainees have said that they were paid as low as “$1 and $4 per day.“ Barahona said his experience inside Stewart left him feeling mistreated by a company profiting from the detention of thousands of people like him.

“It’s a business. They’re making money off of everything they can,” Barahona-Marriaga said.

The only way people were able to be heard, he said, was through agitating and organizing against the conditions they faced inside the detention centers. In 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Barahona-Marriaga participated in a hunger strike at Irwin County Detention Center. For at least nine days, Barahona went without food, water, or medicine to demand the facility take measures to stem the spread of the virus.

Speaking from his experience, Barahona said that what detainees are doing inside Stewart right now is the perfect way to get the attention of people who can affect change.

Puertas told Unicorn Riot that while the pending hunger strike is one example of resistance, people regularly agitate for humane treatment inside Stewart. From small acts including refusing meals and sabotaging infrastructure, to larger confrontations like the standoff a few weeks back, detainees are constantly rebelling against the conditions they face in Stewart, he said.

With a larger, organized push, Puertas and other hunger strikers are hopeful to find some lasting relief from the conditions they’re subjected to inside SDC.

Related coverage:

Indigenous Climate Activist Victor Puertas Remains in Custody Despite No Indictment [July 2023]

Clergy Demand Release of Indigenous Climate Activist Victor Puertas from ICE Detention [June 2023]

Reports of Forced Sterilizations in ICE Facility Spark Protest [Sept. 2020]

Immigrant Children Eulogized at ‘Close The Camps’ Rally [Aug. 2019]

‘I Can’t Take This Shit No More’: Alabama Prisoner Takes a Stand [Aug. 2023]

Prison Strike 2018: Tipping the Scale of the Conversation [Aug. 2018]

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.