The Case of Marvin Haynes – Part Three: The Framing of Marvin Haynes

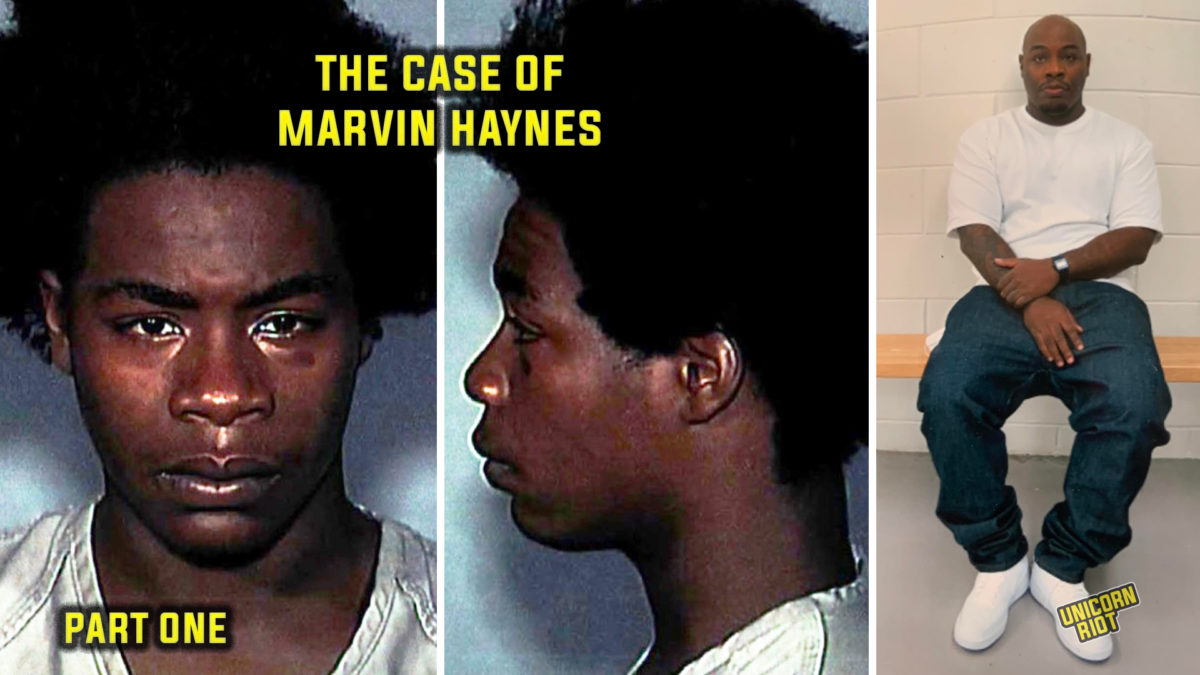

The third of four articles from Unicorn Riot’s investigative series into the case of Marvin Haynes, who was sentenced to life in prison in 2006 at the age of 17 for a murder he says he didn’t commit. As of this writing, he remains imprisoned at the Stillwater Correctional Facility.

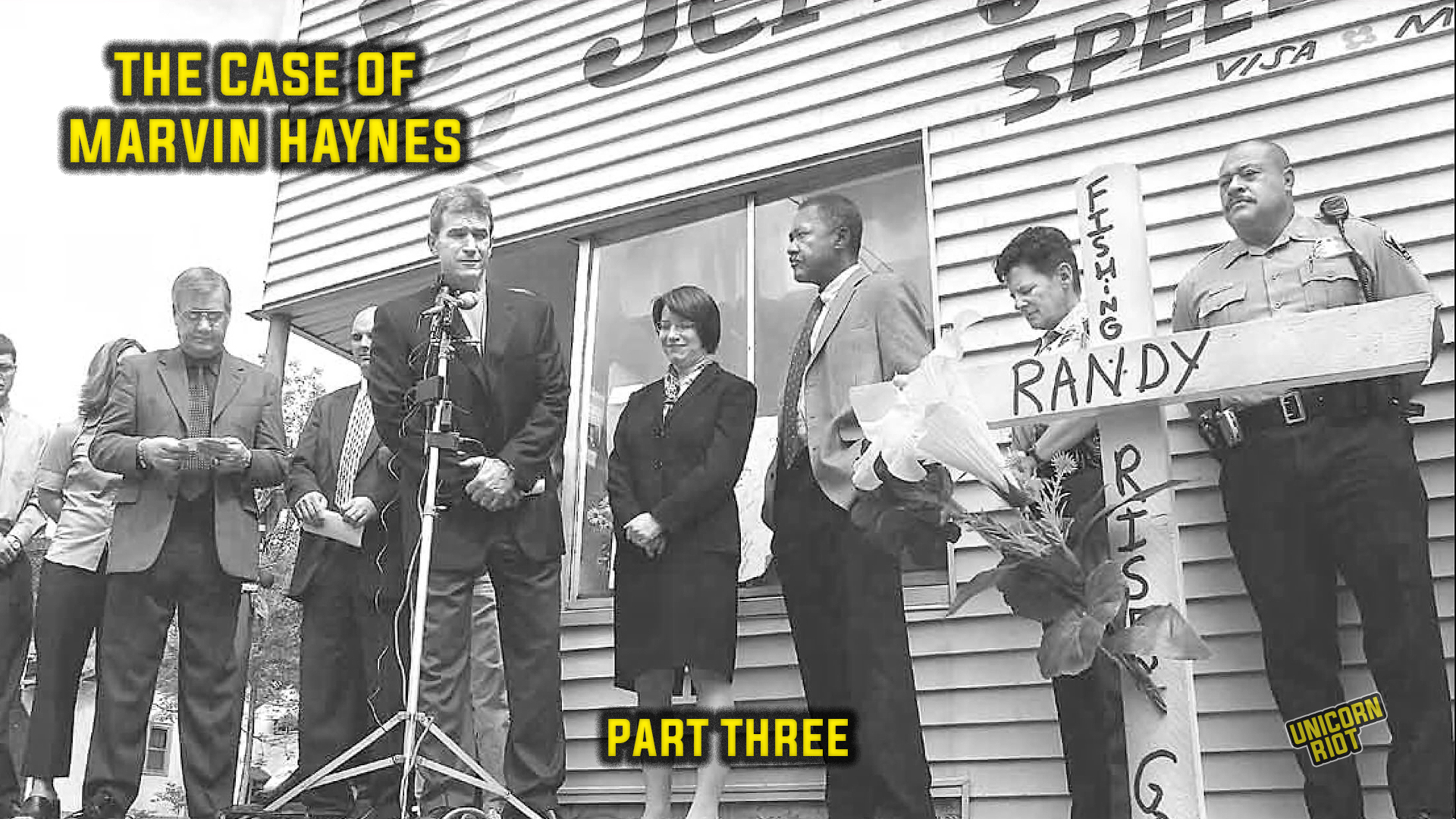

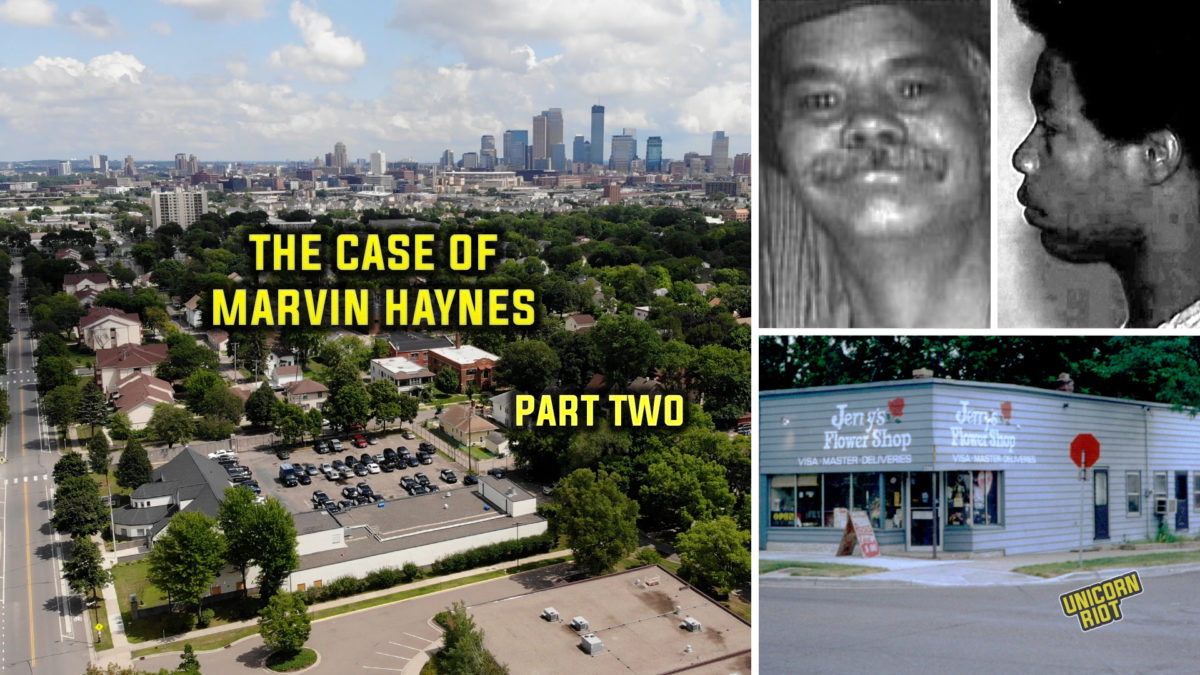

Minneapolis, MN – When Officers Rollins and Smelter pulled up in front of Jerry’s Flower Shop on Sunday morning, May 16, 2004, they saw a woman run out the front door. She was screaming.

She told the officers that her brother was inside and that he’d been shot. When they entered the building they found Randy Sherer, 55, lying dead in a pool of blood.

It would take less than three days for police to identify the suspect they became convinced, based upon very little evidence, had committed the murder. In less than four days, they would formally charge 16-year-old Marvin Haynes with first-degree murder with no physical evidence linking him to the crime, even though he did not fit the description of the shooter. In fifteen months, he’d be sentenced to spend the rest of his life in a prison cell.

In this article, we’ll walk you through the investigation and the resulting frame-up of Marvin Haynes. Our narrative follows a tortuous path created decades ago by county attorneys, overly ambitious, racist cops, faulty eyewitness identification procedures, pressure from those in power — including Black community leaders — to find the shooter quickly, and a series of coerced teenage witnesses. That path ends at Minnesota Correctional Facility-Stillwater, where Marvin Haynes and so many men like him sit behind bars.

Four of those teenage witnesses have since recanted their testimonies, providing statements to the Great North Innocence Project describing how they were coerced by police into going along with the frame-up. You can read their statements here. We also visited MCF-Faribault, the state prison where one of the teens who testified against Marvin is now incarcerated. Watch our film featuring the former witness along with Marvin’s sister, family investigator Robert Johnson, former Minneapolis Police Officer Sarah Saarela, and founder of Communities United Against Police Brutality, Michelle Gross.

Along with this article, Unicorn Riot is making thousands of pages of case documents, police reports, interview transcripts, affidavits of witnesses, trial transcripts, and a recent report from the Great North Innocence Project available to the public.

The Case of Marvin Haynes Investigative Series

Part One – Part Two – Part Three – Part Four – The Film – Haynes’ Exoneration

UPDATE: On December 11, 2023, Haynes was exonerated, had his murder conviction vacated and was released from prison. Read our full report.

Within thirty minutes of the shooting, Sergeants Michael Keefe and David Mattson of the Minneapolis Police Department arrived on the scene. As lead investigators on the case, they took charge of the scene and sent officers to interview any possible witnesses.

The sergeants directed officers to use police dogs to track the route the shooter took out of the flower shop. In two separate attempts, dogs tracked the shooter north up the alley at the rear of the flower shop to a concrete pad at the back of 3343 6th St. North, a block away. Police interviewed those living in the house and only one, a young man named Jerry Hare, matched Cynthia McDermid’s descriptions of the shooter.

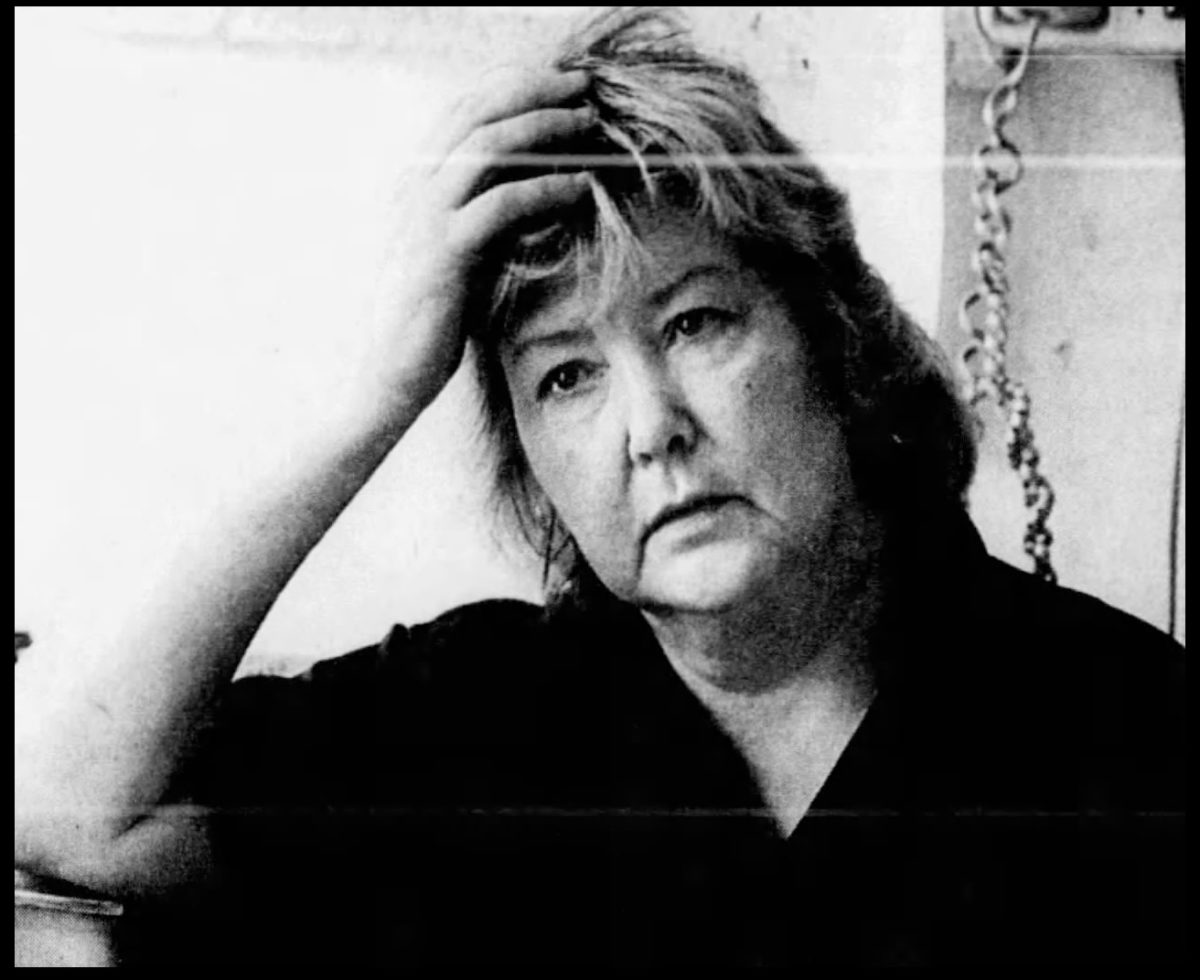

In her initial interviews with police, McDermid told them that the man who shot her brother was an African-American male, 5 feet 10 or 11 inches tall, with close-cropped, natural hair, who weighed about 180 pounds, appeared to be in his early 20s, and spoke “with clarity” and “as if he had an education.” Other physical characteristics, such as the tone of his skin, changed during her various descriptions from “real dark” on the 911 call to “medium” in an interview the following day.

Two hours after the shooting, Sergeants Keefe and Mattson took McDermid down to the police station to show her the first of three photo arrays they’d show her over the next three days. The photo lineup was conducted by another officer, Sergeant Rick Zimmerman, using a “double-blind” procedure designed to increase the integrity of the investigation and reduce bias. According to the officers, Zimmerman was not familiar with the case and did not know which of the photos, if any, contained the image of an actual suspect and which were fillers.

Investigators soon abandon this protocol, which was intended to prevent wrongful conviction of innocent people, without explanation.

The lineup contained six photos, including a photo of Jerry Hare, the young man living at the house identified by police dogs. McDermid was shown the photos one at a time and asked whether she recognized any of the young men. McDermid stopped at photo number two, Jerry Hare, saying that she recognized him from the neighborhood and that he may have been in the flower shop in the past. She also stopped at photo number four, who she said “looked like the suspect.”

The following day, McDermid was shown the same photo array a second time, this time with the photos enlarged. A different officer, Sergeant Bruce Folkens, conducted the lineup. According to Sergeant Folkens’ testimony later in court, McDermid again identified the same individual, number four, as the suspect, “and she further added that she wasn’t a hundred percent positive but more like 75 to 80 percent,” Folkens recalled.

The young man in photo number four was 20-year-old Max Bolden, whose photo had been used as a filler. Weeks later, police called Bolden’s mother at work to inquire about his whereabouts during the weekend of the murder. His mother, Tawanda Logan, told police that Bolden had been staying with family in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Police followed up with family members in South Dakota, who confirmed his alibi. Bolden is now serving a life sentence in South Dakota for an unrelated murder.

While McDermid was at the police station looking at photographs in the hours after her brother’s murder, police were collecting evidence at the scene. Sergeant Rodney Timmerman, with the Minneapolis Police Department’s Crime Lab, searched the flower shop for prints and other physical evidence. Timmerman found seven fingerprints, two of which would end up belonging to officers responding to the scene that day. None of the other five matched Marvin Haynes.

Forty-eight hours after the murder of Randy Sherer, Sergeants Keefe and Mattson found themselves with little to go on. Their only suspect, Jerry Hare, had been identified by their primary witness as just a kid from the neighborhood (police later confirmed that Hare was elsewhere at the time of the murder). In the process of identifying him, McDermid had shown how unreliable her memory was by pointing to a random filler photo and saying she was 75-80% sure it was the suspect.

Just then, according to a report (pdf) filed by Sergeant Mattson at the time, he got “an anonymous tip that the shooter in the flower shop murder was a 16 year old black male known as ‘Little Marvin.’”

The next morning, Sergeant Mattson called the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office to request Haynes’ juvenile records. They found that Haynes had failed to appear for court the previous day. Seeing it as an opportunity to bring Haynes in for questioning without any evidence linking him to the murder, Sergeant Mattson requested that a warrant be issued for Haynes’ arrest and sent officers to pick him up at his home. After interrogating him, they held him at the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center on suspicion of murder.

At trial, the prosecutor in the case spoke about “an unknown confidential reliable informant that provided some information to a member of the black community who provided it to us.” No information was ever given about the source of this information that appeared, just in the nick of time, and turned the police’s attention to a previously unconnected person, Marvin Haynes.

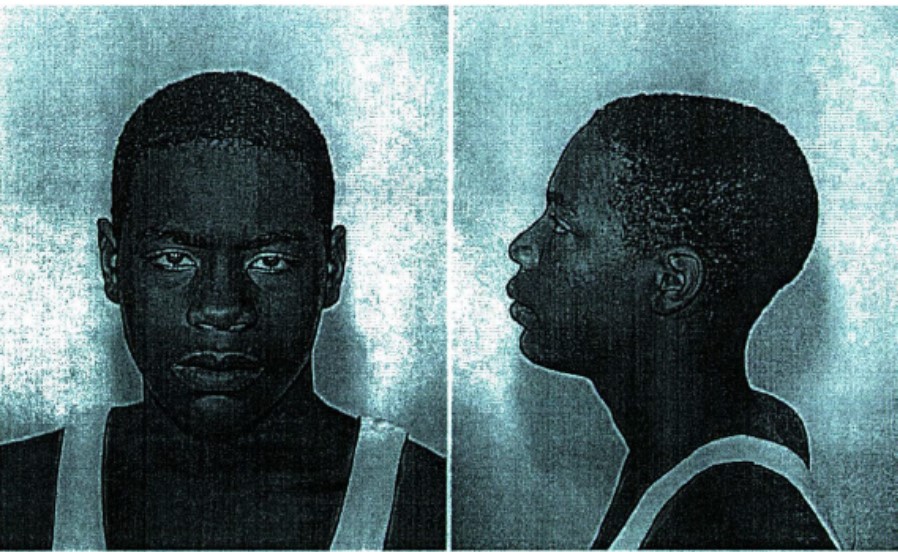

In some ways, Marvin was an unlikely suspect. According to booking records, he was 5 feet, 7 inches tall, weighed 130 pounds, had a 4-inch Afro at the time of the shooting, and didn’t look a day older than his 16 years. Police were looking for a suspect who was 3-4 inches taller, 50 pounds heavier, and at least 4 years older who spoke “with clarity” and “as if he had an education.” Marvin had dropped out of remedial school, could hardly read, mumbled his words, spoke in slang.

In other ways, he was the perfect suspect in the eyes of the Minneapolis Police Department. He was a young, Black male in a city that offered him few prospects. He’d had a string of past contacts with police and admitted to officers during his interrogation that he sometimes sold a little bit of weed. In cities all across the country, young men just like him were caught up in situations just like this. He was an easy target.

On the same day that Sergeant Mattson received his anonymous tip, a 14-year-old boy named Ravi Seeley reluctantly told a school police officer at St. Louis Park Junior High that he had been passing the flower shop after church when he heard a shot and saw someone run out the store. He described the person as “a slender black male” with a “natural haircut possibly faded on the sides.”

The next day, investigators showed McDermid and Seeley a photo array. While it was the first time Seeley was participating in a lineup, for McDermid it was the third. The day after that, they conducted an in-person, live lineup at the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center for both eyewitnesses. Both times, McDermid and Seeley identified the new suspect, Marvin Haynes, as the shooter, although Seeley would later testify in court that he “was very confused I think between two people,” that he was “shaky on it,” and that he had tried to tell the officers during the lineup that he wasn’t sure about his identification.

McDermid, on the other hand, said “he looks like him.” At trial, she would testify that she had “no doubt” in her identification.

Parsing through the evidence, it’s hard to understand the discrepancies between McDermid’s descriptions of the man who killed her brother and her later certainty that the shooter was Marvin Haynes. Unfortunately, modern psychology tells us that such discrepancies are not at all uncommon.

The explanation may lie in the fallibility of human memory.

In the mid-to-late 1970s, psychologists studying eyewitness identification began publishing some worrisome results (pdf). In experiment after experiment, they were able to show that witnesses could be easily swayed into misidentifying innocent people by those individuals, usually cops, administering the tests. In a variety of situations, the scientists got well-meaning people to wrongly identify suspects through simple manipulations of circumstances common in police stations across the country.

This information largely confirmed what those occupying the country’s prisons and overpoliced urban neighborhoods already knew quite well — the cops can get witnesses to lie on you.

In the 1990s, developments in forensic DNA technology made it possible to test claims of innocence in cases where defendants and their attorneys had previously hit a wall. Bits of evidence still on file could be tested, and, with greater accuracy than before, investigators could tell whether a defendant was guilty.

The result was a wave of exonerations of innocent people, some of whom had spent decades of their lives in prison for crimes they had not committed. The majority of those people had been convicted based upon eyewitness testimony that could now be proven untrue. Given the fact that only a small number of cases involved DNA-rich evidence that was still available, it was easy to extrapolate that the true number of people wrongfully convicted based on eyewitness testimony in the country was actually much larger. With the psychological data about the fallibility of eyewitnesses now on hand, it wasn’t hard to explain why.

The confluence of these two developments caused something of a crisis in a criminal justice system eager to justify itself to the public. In 1994, President Clinton had passed his now-infamous crime bill — still the largest federal crime legislation ever passed — which fueled an unprecedented prison-building boom over the next decade. Between 1990 and 2005, the number of state and federal adult prisons rose by 43%. If eyewitnesses couldn’t be trusted, how could politicians, police, and prosecutors justify their frenzied efforts to lock millions of people in cages based on cases that relied heavily on their testimony?

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, researchers and law enforcement specialists, in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Justice and city and county attorneys’ offices around the country, were stepping up to resolve the crisis. The system wasn’t broken, they assured everyone, it simply needed to be updated. One of those prosecutors responding to the call was then-Hennepin County Attorney Amy Klobuchar.

“In the interest of justice,” wrote Klobuchar in an article (pdf) in 2005, “the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office decided in 2003 that it was time to improve eyewitness identifications by adopting a new lineup protocol that would minimize the risk of mistaken identifications and would be workable for local police.”

This new protocol, which governed both in-person and photographic lineups, was initiated six months before the murder of Randy Sherer. It made some of the best practices known to researchers at the time the standard policy for all cases handled by the Minneapolis Police Department’s Central Investigations unit, which handled all violent crimes.

In 2020, a version of these protocols was made state law.

The protocols were designed in collaboration with Professor Nancy Steblay of Augsburg University in Minneapolis, one of the leading researchers in eyewitness science and field lineup identification procedures nationwide. Dr. Steblay had received a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice to conduct research, in collaboration with Klobuchar’s office, on the implementation of the new regulations.

In theory, the new regulations should have marked the beginning of a new era in Minneapolis criminal investigations by cutting wrongful convictions to a minimum. The reality, however, was quite different.

The procedures triumphantly spelled out by Klobuchar in her article were largely ignored by investigators working on the flower shop murder. Where they were followed, they were frequently followed incorrectly. Other aspects of the lineups, while not explicitly in violation of protocol, have since been shown to increase the risks of witnesses accusing innocent people of crimes.

“Mistaken eyewitness identifications have not been a notable problem in Minnesota,” wrote Klobuchar in 2004.

Unfortunately for Marvin Haynes, it would take 18 years to prove her wrong.

With Haynes now their primary suspect, Sergeants Keefe and Mattson drove to the home of Cindy McDermid, their main witness, to conduct the third lineup. This time, they would conduct the procedure themselves.

Without any factual evidence linking Haynes to the crime, they hoped to get McDermid to identify him as the shooter. Adding a suspect to a lineup based on a hunch, with no actual factual evidence linking them to the crime, is a common practice in police stations across the country. It’s also been proven to lead to wrongful convictions.

In 2020, the American Psychological Association (APA) convened a panel to produce a report making recommendations for handling eyewitness testimony. “Conducting lineups in the absence of evidence-based reasons for suspicion is a risk factor for mistaken identification,” wrote the authors of the 2020 report (pdf). Evidence-based suspicion means “that there is articulable evidence that leads to a reasonable inference that a particular person, to the exclusion of most other people, likely committed the crime in question.”

When they added Haynes’ photo to their array that morning, Sergeants Keefe and Mattson did not have evidence-based suspicion that Marvin Haynes was the shooter, and they still didn’t have it on the day Haynes was sent to prison for the rest of his life.

In previous photo lineups, the two investigators had followed department protocol by requesting that officers not involved in the investigation conduct the procedure. This protocol was designed to prevent the investigating officers from, intentionally or not, tipping the witness off about which photo contained their suspect and which was a filler.

After two occasions in which they didn’t get the results they were looking for, the pair abandoned the protocol, deciding instead to conduct the lineups themselves. Rather than using the booking photo taken three days after the shooting, which showed Haynes with a four-inch Afro, Mattson and Keefe chose to use a two-year-old photo that showed Marvin at 14 with close-cropped hair, more closely resembling McDermid’s description.

These decisions are not explained in their reports. According to Mattson’s report (pdf), when McDermid got to Haynes’ photo, she “gasped, placed her right index finger on his photo and said, ‘Oh my God that’s him.’”

The next day, Sergeants Keefe and Mattson conducted a fourth lineup, this time with live subjects instead of photos. They did it at the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center using five filler subjects chosen by Detention Center staff from the institution’s population. The sixth subject was Marvin Haynes.

“All of the fillers changed from the photo array to the live lineup,” wrote eyewitness expert Dr. Nancy Steblay in a report (pdf) on Haynes’ case. “Otherwise stated, Mr. Haynes was the only lineup member who was shown twice.”

Eyewitness identification science has shown that repeating the lineup process “contaminates” the witness’ memory. “There is only one uncontaminated opportunity for a given eyewitness to make an identification of a particular subject,” wrote the authors of the APA’s report. “Any subsequent identification test with that same eyewitness and that same suspect is contaminated by the eyewitness’s experience on the initial test.”

Professor Steblay wrote in her report that “a repeated lineup is a very bad idea […] ” In order to avoid false identifications, “a witness’s memory should be tested only once — and from a proper procedure.”

Further, showing a witness the same lineup twice can result in what researchers call the “commitment effect,” which occurs when a witness misidentifies a suspect and is then shown another lineup, also containing the suspect. “The initial identification,” wrote the APA authors, “even if mistaken, causes the witness to simply repeat the same identification in the second identification procedure.” Repeating a lineup procedure “leads to artificially elevated levels of eyewitness confidence.”

In fact, according to eyewitness science, McDermid should not have been considered a reliable witness after she wrongly identified a filler as the shooter during the first lineup. “In short, a filler identification should not be considered a ‘non-event,’” wrote Dr. Steblay. “Filler identifications are a form of exculpatory evidence for the suspect in the lineup and reflect poorly on the witness’s ability to take on future identification tasks.”

McDermid and Seeley each watched the lineup separately from behind a one-way mirror, with Sergeant Keefe leading the subjects into the room and Sergeant Mattson standing behind the witnesses. The video of the lineup shows a small office with cinder block walls and a door with a glass window. A wrinkled piece of paper taped to the door bears a message long forgotten. The door is open, and the camera shows what looks like a classroom beyond, with tables and chairs of cheap plastic. At the edge of the camera’s view large windows shine, saturating the frame with sunlight.

In the foreground is Sergeant Keefe, a lean, severe man with a short buzz cut. He’s holding a large, white sheet of paper awkwardly in both hands, staring into the camera. It has a numeral 1 on it.

“One,” he says and steps forward. “Come on in.” He gestures to someone in the hallway, out of sight.

A young man limps in wearing a V-neck smock of coarse material that looks hunter green in the grainy video. His hair is in two braids on either side of his head with a ponytail in the back. He moves with difficulty, favoring an injured foot or ankle.

“Turn to the right,” Sergeant Keefe orders him. And after a moment, “OK, turn back. Turn to the left.”

“OK, I want you to look at the window and show your teeth,” Sergeant Keefe tells him.

The kid, looking at the officer, bears his teeth. He looks at the window with an awkward, forced grimace. The camera zooms in on his face, showing gold grills on the bottom.

“OK, now I want you to repeat after me. Look right at the window and repeat after me,” says Sergeant Keefe, off camera, flipping through papers. “Say it in a loud and demanding voice. ‘Don’t move.’”

“Don’t move,” the kid repeats.

“Where’s the tape?” prompts Sergeant Keefe. The call-and-response continues. The kid says what he’s told to say: “This is no joke,” “I want the money,” “No till,” and “I want the money that is hidden here.”

Each subject is called in by number, six in total. A string of Black boys, paraded before witnesses, forced to show their teeth and speak on cue. The pattern repeats until subject number four, when Sergeant Keefe breaks the pattern.

“Number 4,” says Sergeant Keefe. “Come on in, Marvin.”

He goes through the same routine with Marvin Haynes, who looks even younger and more confused than the rest.

“OK that’s it Marvin, you’re done,” Sergeant Keefe says, using his name again. Throughout the rest of the lineup, none of the other subjects are called out by name.

In police lineups, the purpose of the fillers is to provide the witness a variety of subjects who fit the general description of the suspect. In 2005, Klobuchar, writing as Hennepin County Attorney, explained the importance of choosing fillers that match the witnesses’ description of the suspect, “at least as much as the suspect does.” Overall, Klobuchar writes, “the most important goal of this recommendation is that the suspect should not stand out relative to the fillers.”

It goes without saying that an investigator calling out only his prime suspect by name contaminates the lineup. Nonetheless, the veracity of the eyewitness identification that followed was used by police, prosecutors, judge, and jury to send a kid to jail for life.

When Marvin was led into the room, McDermid “sat bolt upright in her chair and gasped,” according to Sgt. Mattson’s reports, but then she said that “her mind went traumatic.” When the subjects came into the room for the second time, McDermid wasn’t able to positively identify Haynes, saying that she was “having problems concentrating” and “she felt she was blending them all together.”

Fourteen-year-old Ravi Seeley told police, “he looks like who I saw,” when Haynes came into the room, but also told police he wasn’t really sure. Later, at trial, he would repeatedly say that he wasn’t confident of his identification.

Eighteen years later, Seeley gave a statement (pdf) to the Innocence Project recanting much of his testimony. “I felt the police officers pressured me to make an identification both times around,” said Seeley, referring to both lineups. “The officers led me to believe this person was dangerous, that I needed to help them solve the case, and that I could get in trouble if I was not helpful.”

Seeley is just one of the many kids caught up in Sgts. Keefe and Mattson’s abusive investigation. Through intimidation and pressuring, the pair wielded their authority to get kids to lie, causing them enormous stress in the process.

“Only 14 years old,” wrote (pdf) Seeley last year, “I had never been interviewed by police or been involved in anything like this. I was terrified about what could happen to me if I was not cooperative […] As a young and impressionable teenager, the police officers pressured me into making potentially inaccurate identifications and telling the officers what I believed they wanted to hear.”

With positive identifications now secured from their two main witnesses, Sergeants Keefe and Mattson began building their case. Over the course of the next two months, they would speak to anyone they could, trying to find witnesses who would testify that Marvin had told them he’d killed someone or that they’d seen him with a gun. They would build a team of kids — ages 14-17 — willing to give statements against Haynes.

Four of these witnesses, either at trial or since, have said that police pressured them into talking. One of them, Isiah Harper, would become one of the state’s key witnesses, testifying that Haynes, his first cousin, had told him he had “hit a lick” and had shot an old white man.

In an interview with Unicorn Riot, Harper admitted that he’d lied on the witness stand after being threatened with decades in prison by police. He was only 14 years old at the time.

“If you see the statement you’ll see that I say that Marvin had called me crying saying that he’d killed a man on the corner,” said Harper. “That’s what they told me to say. And that’s what I went with after they put me in the jail cell and threatened me over and over.”

On October 11, 2004, Haynes would be tried for murder in Hennepin County District Court. Prosecutors would convict Haynes without any physical evidence linking him to the murder, based upon flawed eyewitness identifications, and the testimonies of a handful of kids.

This is the third of four articles in Unicorn Riot’s investigation into the case of Marvin Haynes. Part one brings you to the interrogation room with police and 16-year-old Haynes. Part two takes a close look at the murder of Randy Sherer and the context of the economic abandonment of Minneapolis’ Northside in which it occurred. Part four goes over the murder trial that led to Haynes conviction and life sentence. See our 33-minute film on The Case of Marvin Haynes below.

We thank Marvin Haynes and his family and supporters for sharing case documents with us.

UPDATE: On December 11, 2023, Haynes was exonerated, had his murder conviction vacated and was released from prison. Read our full report.

Cover image source Bruce Bisping/Start Tribune, 2004.

Documents for Download

- Judge William Koch’s order to vacate Haynes’ conviction – December 11, 2023, 6 pages

- Amended Petition for Post-Conviction Relief – October 4, 2023, 11 pages

- Minneapolis Police Department Case Report with Narratives – 190 pages (Separate and less-redacted supplements from the report are available in Unicorn Riot’s Vault Server)

- 911 Call Transcript – 6 pages

Trial and Appeal Documents:

- Marvin Haynes Trial Transcript – August 2005, 1,593 pages

- State of Minnesota, Appellant, vs. Marvin Haynes, Jr., Respondent. Court of Appeals Unpublished – April 5, 2005, 4 pages

- Marvin Haynes Appellant’s Brief – May 23, 2006, 50 pages

- State of Minnesota Respondent’s Brief – July 10, 2006, 48 pages

- State of Minnesota Supreme Court Opinion – January 4, 2007, 12 pages

Application to the Conviction Review Unit by the Great North Innocence Project:

- Application for Relief on Behalf of Marvin Haynes – Dec. 15, 2022, 72 pages

- Affidavits by the Innocence Project – 8 pdfs

- Marvin Haynes Certificates – 10 pages

The Case of Marvin Haynes – An Investigative Series

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.