The Case of Marvin Haynes – Part Four: The Trials of Marvin Haynes

This is the fourth and final article in Unicorn Riot’s investigative series into the case of Marvin Haynes, who was sentenced to life in prison at the age of 17 for a murder he says he didn’t commit. As of this writing, he remains imprisoned at the Stillwater Correctional Facility.

Hennepin County District Court, Minneapolis, Minnesota. September 2, 2005. The trial of Marvin Haynes began 12 days ago, just 15 ½ months after the murder of Randy Sherer at Jerry’s Flower Shop on the Northside of Minneapolis. Haynes, now 17, sits at the defense table and he watches as the jury files in and takes their seats and they glance up at him and make eye contact and look away.

Haynes has been in jail these 471 days and the days have aged him. Gone is the crying boy in the interrogation room, asking for his mother. He has followed closely as the prosecution builds its case, as his cousin and three other kids from his neighborhood lie, saying he told them he’d shot a man, that he was planning to ‘hit a lick.’ Still, he has maintained some hope, some faith in the system of justice and in its ability to sort truth from falsehood. For if there is no justice here, then where?

The following occurs at 7:23 p.m. in a courtroom in the Hennepin County Government Center.

The Court: Members of the jury, have you selected a foreperson? Jurors: Yes, we have. The Court: And have you reached a verdict? Jurors: Yes, we have. The Court: Will you please hand the verdict to the deputy? Defendant please rise. The clerk will now read the verdict. The Clerk: We, the jury, find the defendant guilty of the charge of murder in the first degree. We, the jury, find the defendant guilty of the charge of assault in the second degree. The Court: Would the defendant request the jury be polled? Mr. Benson: Yes, Your Honor.

At the Defense attorney’s request, each juror stood and accounted “yes” for their decision.

Like a divine invocation or a desperate plea for justice, just at the moment when the people of Minneapolis finally rendered Marvin silent, he instead spoke:

The Defendant [Marvin Haynes]: Man, I didn't kill that man. Man. They all going to burn in hell for that, I swear. The Court: Court will set sentencing for September 27th, nine o'clock. The Defendant [Marvin Haynes]: They can all burn in hell for this right here.

Whereupon, the proceedings conclude at 7:25 p.m.

The Case of Marvin Haynes – A Unicorn Riot Investigative Series

Part One – Part Two – Part Three – Part Four – The Film – Haynes’ Exoneration

UPDATE: On December 11, 2023, Haynes was exonerated, had his murder conviction vacated and was released from prison. Read our full report.

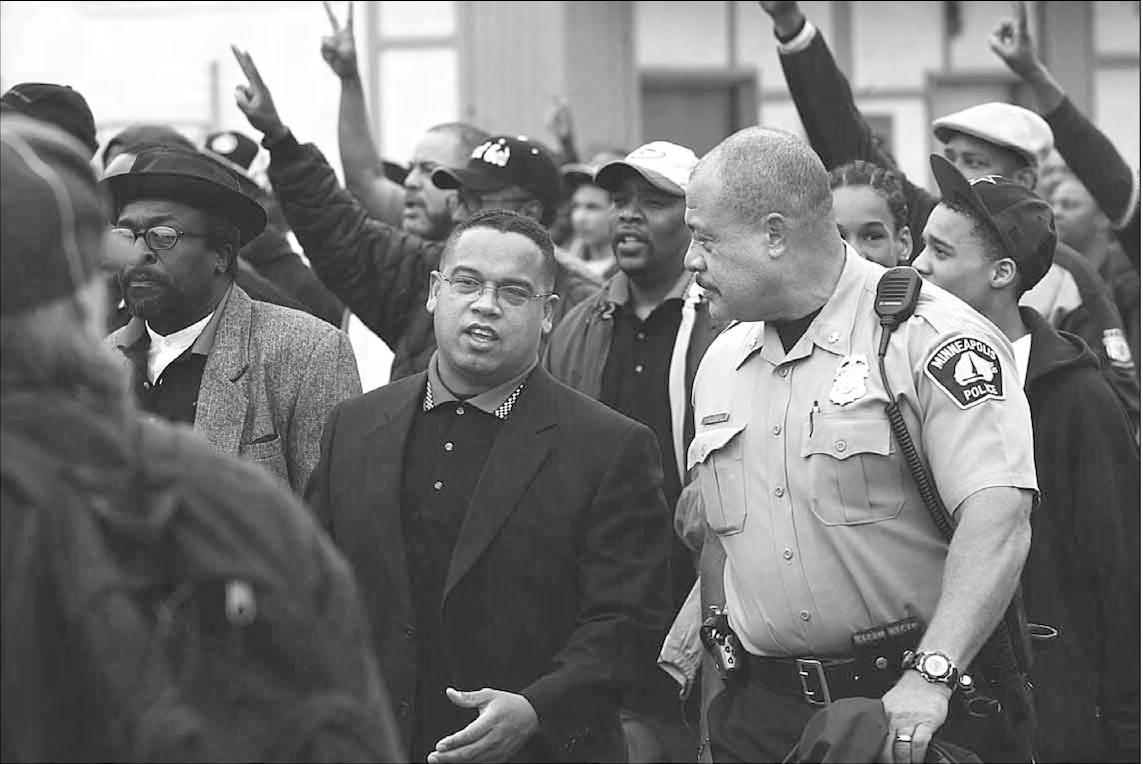

The streets of North Minneapolis. Friday, May 21, 2004. It’s 15 ½ months before a jury will find Marvin Haynes guilty of murder in the first degree.

About 500 residents, politicians and police officers, mostly Black men, march through the residential neighborhood. Tall oaks and maples shade the lawns. People watch from their porches, driveways. Lyndale Avenue North, Lowry Avenue North, 33rd Avenue North, Fremont Avenue North.

Randy Sherer is already dead. He was shot five days ago during a botched robbery at Jerry’s Flower Shop, which stands in the background. The windows of the shop are covered with handmade signs scrawled with messages of mourning and support. A light post out front is dotted with dyed pink, red, and blue carnations, packing tape clinging to their plastic wrappings. A makeshift cross bearing Randy’s name stands hammered into the grass reading “Randy” and the words “fishing” and “golf.”

The crowd walks slowly through the streets and a reporter weaves through the crowd, getting quotes from community leaders, cops, young men. “We’re policing ourselves,” says Spike Moss, a Black community organizer with close ties to the police. “We’re taking back our streets. We’re the ones who are putting our own into the ground.”

The reporter speaks to Minneapolis Police Inspector Don Banham, who walks the entire length of the march. “I’m glad they’re showing unity in the community and raising the consciousness level,” says Banham. “I’m in full support of any participation to help police make their communities safer. We can’t do it alone.”

The leaders of the march implore people to cooperate with police. “We have to debunk this notion that this is snitching,” says Jerry McAfee, president of MAD DADS, a group which performs “patrols” on the streets of North Minneapolis. “Our people know who did this and yet they say nothing. Who are you protecting? Murderers, who if they did it once, they will do it again. What type of vehicle do we need to put forward to get folks to speak up?”

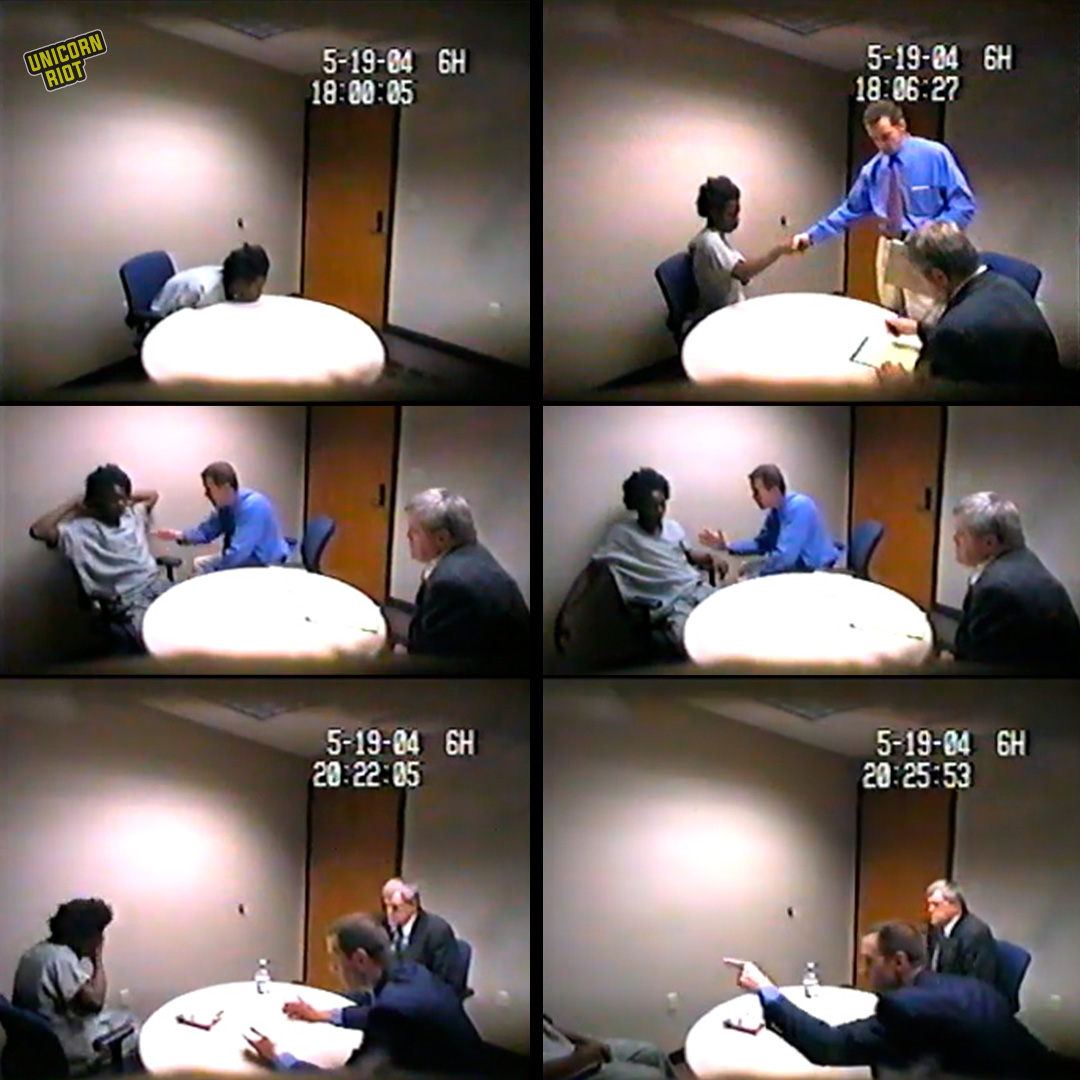

When Sgt. David Mattson received an anonymous tip from a “source within the community” that a 16-year-old kid named Marvin Haynes had shot Randy Sherer, both he and his partner, Sgt. Michael Keefe, became convinced, based upon very little evidence, that it was true. They had Haynes picked up on an outstanding warrant for failing to appear to court on an unrelated misdemeanor charge and, when he wouldn’t crack under interrogation, they started scrambling to find other ways to build a case against him quickly.

The two investigators were moving fast. The pressure upon them to solve this case was immense.

While Sgts. Mattson and Keefe were preparing for a trial in Hennepin County District Court, another trial was taking place in the streets and in the news. A coalition of Black community leaders, politicians, and police declared Haynes guilty long before he ever entered a courtroom.

Five days after the shooting, with no physical evidence whatsoever linking him to the murder, Police Chief Bill McManus described a “double tragedy” to reporters–Sherer’s death and the “murder by a young man who lived in the neighborhood who is now lost.” It would appear that Haynes, who sat confused and bored at the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center, had already been declared guilty by those holding power in the Twin Cities.

Local organizers sympathetic to the police had already called for a “1,000 Man March” in response to “rising violence,” which they blamed, in large part, on Black men. They declared the need for “unity” and closer ties to the police.

The day after the shooting, Rev. Albert Gallmon Jr., Pastor of the Fellowship Ministry Baptist Church, had announced that he’d already fundraised $2,000 of at total $5,000 he planned to set up as a reward for anyone who called the police with information leading to the arrest of Sherer’s shooter.

With pressure from across the political spectrum and community leaders backing a mass incarceration agenda, the investigators knew they had to gather evidence fast. With the reward putting informants on high alert, the stage was set for a wrongful conviction.

As physical evidence came up dry, Sgts. Keefe and Mattson turned to a reliable source of bad information: jailhouse snitches.

On May 21, 2004, Sgts. Keefe and Mattson interviewed Daquan Bradley and Perez Wrencher, both of whom were locked up at the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center where Haynes was also held. Both Wrencher and Bradley claimed that they had overheard Haynes in jail claiming to have “hit a lick” and “come up.” Wrencher told police Haynes had told him about all the guns he has and about how when he gets back to the block he’s going to “sell dope” and “get his money.” Standard, vague fare of the jailhouse informant.

But Bradley said more. He claimed to have been with Marvin at a mutual friend’s house named Muffy on the morning of the murder and that Marvin had asked him to come along on a robbery. He said Marvin had later told him he “hit a sweet lick and came up” and that he’d shot someone.

“Did he tell you who could have done this robbery with him?” asked the investigators.

“Him, his cousins Six and Poopey,” replied Bradley.

Poopey was a family nickname for Isiah Harper, Haynes’ 14-year-old first cousin. The investigators went to speak with Harper and in him they found their most ambivalent witness. He was close enough to Haynes to make his testimony invaluable, but over the course of the investigation he would prove increasingly unpredictable—oscillating between saying Haynes had told him he’d shot someone and testifying that it wasn’t the case. Later, with the help of a public defender, he’d try to avoid testifying by calling in his Fifth Amendment right to avoid self-incrimination.

More than 18 years later, Harper told Unicorn Riot that police had pressured him to talk. According to Harper, police threw him in a holding cell with adults at the Hennepin County Jail when he wouldn’t say what they wanted him to say. They showed him photos of cars they claimed he’d stolen. “You know you can get half of his time?” Harper remembers them telling him. “If he get 30 you get half of that, if he get 50 you get half of that.”

Eventually, the pressure became too much. Unable to stand up to the adults threatening him, he caved, agreeing to whatever the police wanted him to say. “If you see the statement you’ll see that I say that Marvin had called me crying saying that he’d killed a man on the corner,” Harper told Unicorn Riot in an interview late last year. “That’s what they told me to say. And that’s what I went with after they put me in the jail cell and threatened me over and over.”

Harper’s story offers a view of Sgts. Keefe and Mattson’s interrogation technique, in which they alternate between leading questions and threats. According to Harper, the first conversation he had with the two investigators went like this: “Basically, first they brought me down there. We talked,” said Harper. The cops started by asking how he knew Haynes. “Oh that’s my cousin,” said Harper. “‘Oh, do he call you?’” they asked. “‘Yeah he call me a lot.’ ‘Did he call you and tell you that he killed somebody?’ I’m like, ‘no.’ And then he like ‘you sure?’ I’m like ‘I’m positive.’ Then he got to showing me pictures of stolen cars and stuff that we had. ‘Oh well, do you know we found your fingerprints in his car?’”

After threatening him with jail time for the stolen car, the investigators pivoted back to their leading questions. Harper tells the story: “So that’s when…he got back to the question like, ‘So, did Marvin call you and tell you that he killed someone?’ I’m like, ‘no,’ he like ‘yes, he did.’ I’m like ‘no, he didn’t.’ He’s like, ‘are you going to sit in here and lie?’ I’m like ‘I’m not lying.’ He’s like, ‘so he didn’t say he killed the man on the corner?’ I’m like, ‘no.’ That’s when they started playing the good cop, bad cop situation.”

After several rounds of questioning, Harper agreed with police that Haynes had told him he’d planned to “hit a lick,” that he’d been carrying a chrome revolver and that later Haynes had indeed called him and told him he had “shot a white man.” When asked if Haynes had said why he’d killed the man, Harper responded, “because he wouldn’t give up the money.”

On June 10, 2004, Harper testified before a grand jury convened to formally indict Haynes on first degree murder charges. According to Harper, he testified from the jury stand that the story he’d given police about Haynes’ involvement in the murder was made up, that police had forced him to say it. “And they stopped the tape in there and said, ‘you know you lying on the grand jury, you know you can go to jail for this,’” recounted Harper. “And I’m like ‘I’m not lying, this is the truth.’ And they said, ‘say what was said on the tape.’ And so I did.”

Over a year later, Harper would again testify, this time at Haynes’ trial, and a similar scene would play out. The prosecutor questioned Harper, and he told the jury that everything he’d said in his statement to police was a lie.

“Now you are saying that, that you made everything up that you put in this May 28th statement,” asked Michael Furnstahl, the Hennepin County Prosecutor.

“I been saying that,” responded Harper.

“Excuse me?”

“I been saying that because they threatened me with 15 years.”

Rather than taking Harper’s statements at face value, the judge and jury believed the prosecutor, who told them Harper was afraid to “tell the truth” because of the consequences of snitching in his family and in the broader Black community.

“And he was conflicted in doing that because on the one hand he knows that he could face some jeopardy himself,” said the prosecutor in his closing argument. “On the other hand if he tells the truth he hurts his cousin, his own blood cousin and he has to go home and face his relatives and he did not like that, obviously. So didn’t his conduct speak volumes to you?”

Over the course of the next several months, Sgts. Keefe and Mattson would interview seven other teenagers in an attempt to build their case against Haynes. In late 2022, The Great North Innocence Project released a report (pdf) that included affidavits from four teenagers who say the police pressured them to lie and used interrogation techniques designed to elicit the answers police wanted.

“I felt the police officers pressured me to make an identification,” said Ravi Seeley, the 14-year-old who had seen someone run out of the flower shop moments after the shooting. “The officers led me to believe this person was dangerous, that I needed to help them solve the case, and that I could get in trouble if I was not helpful. In fact, I did not get a clear view of the face of the person running from the flower shop. Only 14 years old, I had never been interviewed by police or been involved with anything like this. I was terrified about what could happen to me if I was not cooperative. That same fear is the reason I did not provide these additional details during my trial testimony. I worried that if I did, I could get in trouble.”

Ashley Toten and Anthony Todd, two more teens pulled into the investigation by Sgts. Keefe and Mattson, told similar stories. Although neither claimed to be witnesses to the shooting, in each case, they had claimed in 2004 or 2005 that Haynes had told them about the murder or that they’d seen him with a gun.

Todd testified at Haynes’ trial. He told the usual story: that he’d seen Haynes at Muffy’s house that morning, that he’d said he planned to ‘hit a lick,’ that Haynes had driven off in a stolen car. Although the basic story repeats, the details change depending on which teenager is telling it. Sometimes the car is a white Chevy, other times a green Explorer. Sometimes Haynes got there at 8 a.m., sometimes not until 11 a.m. Testimony about which other individuals were also there change wildly.

In fact, the only testimony that seems to not change, from his initial interrogation on May 19, 2004, to the present day is the testimony given by Marvin Haynes, who says he stayed out until 3 a.m. the Saturday night before the murder and slept all day Sunday. His testimony is corroborated by his sisters, four of whom provided affidavits to the Innocence Project claiming that they saw Haynes asleep at home shortly before the murder.

When Marvin Haynes walked, shackled, into the Hennepin County District Court on the last day of his trial, he believed that justice would prevail. He looked around the stately courtroom, at the agents of the court—the bailiff with his badge and gun, the judge in his robes, the prosecutor, the ladies and gentlemen of the jury. These were the adults tasked with the maintenance of justice in Minneapolis, the only world he’d ever known.

Since his arrest, from his interrogation in Room 108 at the Minneapolis Police Headquarters to the in person lineup performed by investigators at the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center, Haynes had approached the adults guiding the investigation with a naïve good faith.

In the video of the lineup, Haynes looks up at Sgt. Keefe, mouth slightly agape, awaiting his next order. He is compliant, even submissive, and guileless, turning left and right on command. Even showing his teeth to the witnesses when ordered. During the interrogation, he explains to police over and over what he was doing on the day of the flower shop robbery, how he’d never kill anyone. For hours, he responds to their questions, sharing anything they ask – even opening up about past girlfriends.

Later, at trial, as Assistant Hennepin County Attorney Michael Furnstahl berates him, shoots rapid fire questions at him and twists his words, Haynes’ answers are again abundantly forthcoming. He seems to believe that if he obeys, if he explains himself as clearly as possible, this will all be cleared up. One can imagine him glancing over at the jury as he answers, testing their reactions, even seeking their approval.

When the jury’s foreperson handed the verdict form to the court deputy who read aloud the guilty verdict, Haynes’ world fell into crisis. Not only because he knew he would soon go to prison, but because his faith in man and in man’s systems of justice had crumbled. All that was left to him was some faith that the goodness of the universe could still prevail, that those who had ordered him to the living hell of prison would, upon death, face cosmic justice.

“Man, I didn’t kill that man. They all going to burn in hell for that, I swear.” – Marvin Haynes

To this day, Haynes maintains hope that, despite all evidence to the contrary, those holding positions of power in Minneapolis—Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, Hennepin County Attorney Mary Moriarty, Minnesota Conviction Review Unit Director Carrie Sperling—will act in the interest of justice. That they will finally weigh the evidence for themselves, see the truth, and exonerate him of any wrongdoing.

Since the day he was arrested more than 18 years ago, Haynes’ story has not changed. He has maintained a belief in both the justice of man and the justice of God. It remains to be seen, as the Innocence Project’s report sits gathering dust on the desks and in the file cabinets and inboxes of the powerful, whether his faith is entirely unfounded.

This is the final of the four articles in Unicorn Riot’s investigation into the case of Marvin Haynes. Part one brings you to the interrogation room with police and 16-year-old Haynes. Part two takes a close look at the murder of Randy Sherer and the context of the economic abandonment of Minneapolis’ Northside in which it occurred. Part three examines the investigation into Randy Sherer’s murder and the framing of Marvin Haynes. See our 33-minute film on The Case of Marvin Haynes below.

UPDATE: On December 11, 2023, Haynes was exonerated, had his murder conviction vacated and was released from prison. Read our full report.

Cover image via screenshot from The Case of Marvin Haynes film by Niko Georgiades for Unicorn Riot.

The Case of Marvin Haynes – An Investigative Series

Part One – Part Two – Part Three – Part Four – The Film – Haynes’ Exoneration

Documents for Download

- Judge William Koch’s order to vacate Haynes’ conviction – December 11, 2023, 6 pages

- Amended Petition for Post-Conviction Relief – October 4, 2023, 11 pages

- Minneapolis Police Department Case Report with Narratives – 190 pages (Separate and less-redacted supplements from the report are available in Unicorn Riot’s Vault Server)

- 911 Call Transcript – 6 pages

Trial and Appeal Documents:

- Marvin Haynes Trial Transcript – August 2005, 1,593 pages

- State of Minnesota, Appellant, vs. Marvin Haynes, Jr., Respondent. Court of Appeals Unpublished – April 5, 2005, 4 pages

- Marvin Haynes Appellant’s Brief – May 23, 2006, 50 pages

- State of Minnesota Respondent’s Brief – July 10, 2006, 48 pages

- State of Minnesota Supreme Court Opinion – January 4, 2007, 12 pages

Application to the Conviction Review Unit by the Great North Innocence Project:

- Application for Relief on Behalf of Marvin Haynes – Dec. 15, 2022, 72 pages

- Affidavits by the Innocence Project – 8 pdfs

- Marvin Haynes Certificates – 10 pages

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.