The Story of Chris Kaba: How London Police Hide Behind the Thin Blue Line

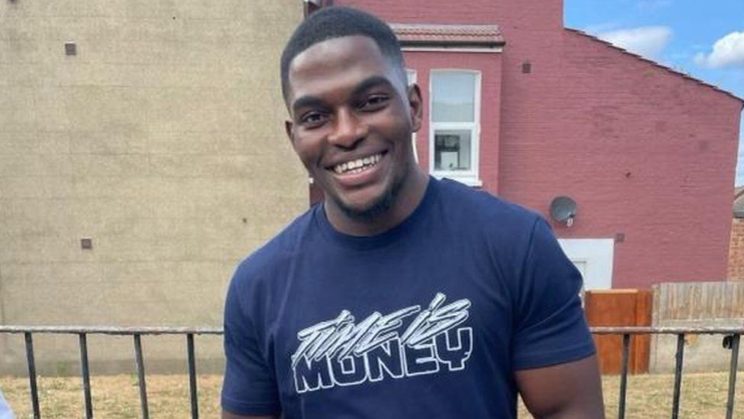

London, United Kingdom — Chris Kaba, 24, was unarmed when he was fatally shot by police in Streatham Hill, South London on Sept. 5, 2022. Kaba was the eldest of three brothers raised by parents from the Democratic Republic of Congo. He lived in Wembley, west London, worked on a construction site and was expecting his first child with his fiancé.

On the night of what’s now officially charged as a murder by prosecutors, Kaba was driving a car that had been allegedly linked to a “firearms incident” the previous day through an automatic number plate recognition system (ANPR).

Kaba was a drill rapper with the hip-hop collective “67” and went by the stage name “Madix” and “Itch.” 67, like other drill groups has been labelled as a “criminal gang” by police and has thus been under significant police surveillance and repression over the years. Kaba’s family has not pointed to his rapping past as a reason they believe he was killed.

Kaba was followed by an unmarked police car in which armed officers from the Metropolitan Police’s Special Firearms Command were riding. Around 10 p.m. Kaba was subjected to a “hard stop” and his car was blocked by two patrol cars. A forced stop – or “hard stop,” as it is often referred to by the public, is when a vehicle is stopped by the police without prior warning or by the positioning of police vehicles to block the movement of a car.

Firearms Officer NX121 approached the car on foot and fired a single shot through the windshield of the car, hitting Chris Kaba. At 10:07 p.m. an ambulance was called. Kaba died at two hours later at 12:16 a.m. on September 6 in a nearby hospital. A post-mortem examination showed that Kaba died from a single gunshot wound to the head. Police immediately notified the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC). Chris’ family was notified of his death at 11 a.m.

Two days after the killing, in a statement released through the organization INQUEST, the family demanded to know whether Chris was carrying a weapon, called for a homicide investigation and questioned whether he would have been shot if he were white. INQUEST is a longstanding organization that labels themselves as “the only charity providing expertise on state related deaths and their investigation to bereaved people, lawyers, advice and support agencies, the media and parliamentarians.”

“We are devastated; we need answers and we need accountability. We are worried that if Chris had not been Black, he would have been arrested on Monday evening and not had his life cut short.”

The same evening, the IOPC confirmed that he was unarmed. It took 48 hours to search his car. According to the IOPC, “no non-police firearms” were found in the car or at the crime scene. On Sept. 9, four days after the fatal shooting and after protests from the family, the IOPC announced that a homicide investigation would be conducted.

On the Saturday after the killing, thousands of people took part in a large protest in Scotland Yard. Two days later on September 12, 2022, Officer NX121, the officer who shot Chris Kaba, was suspended from duties. The officer remained anonymous as the IOPC investigation was ongoing and has since been granted CPR 39, a law allowing his identity to be kept secret.

Calling for justice one year after Kaba was killed, hundreds gathered to protest in London. See video below.

Just days after the justice march, on September 20, 2023, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) announced that the Metropolitan Police officer who shot Chris Kaba had been charged with murder.

Over the past year, Chris Kaba’s family has repeatedly complained about delays and lack of information on the part of the IOPC and the CPS. Prosecutors have been in possession of the evidence file compiled by the Independent Office of Police.

INQUEST has published the following statistics based off reporting since 1990:

- There have been 1,873 deaths in or following police custody or contact in England and Wales.

- There have been 80 fatal police shootings; 33 of them by London’s Metropolitan Police.

- The murder charge against Officer NX121 is the twelfth murder and/or manslaughter charge to have been brought against an on-duty police officer involved in a death since 1990, and the fourth murder charge to be brought in relation to a police shooting.

- Only one successful prosecution of a police officer for manslaughter has occurred and it happened in 2021 following the death of Dalian Atkinson. There have been none for murder.

Who is watching the watchdog? Police Accountability in the UK

Like many others before them, the Kaba family had to deal with the Independent Office for Police Conduct in their quest for justice. Established in 2018, the IOPC is the latest attempt to restore legitimacy to police allowed to investigate, judge and often whitewash their own wrongdoing. It is the successor to the discredited Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC). The Home Office promised in 2018 that the new body would ensure “greater accountability to the public.”

The IOPC is meant to oversee the police complaints system, which is the only way an individual police officer can be disciplined, suspended from duty or prosecuted for their misconduct. However, the IOPC does not actually investigate many allegations of police misconduct on its own. The IOPC’s task is to investigate more serious complaints of police misconduct, such as when someone dies in police custody, and to decide whether the personnel involved will face an internal hearing for misconduct or a criminal prosecution. As a result, the majority of complaints are handled internally by local police forces.

There are some improvements over its predecessors: the IOPC can now take over investigations directly without waiting for the case to be referred to it by the local police authority. The IOPC can also reopen investigations that were previously closed. However, advocates and families continue to say that it appears not much has changed and that the IOPC is not using its new powers.

Of over 23,000 complaints made about poor policing between 2020-2021, only 18 resulted in a police officer facing a misconduct meeting or hearing.

Data released in 2022 by the Home Office showed that 14,393 complaints were made against police officers in England and Wales from January to April 2021. Of those, 92% faced no action and only 1% were referred to a formal process to hear cases, initiated when an officer has a case to answer for misconduct or gross misconduct.

Nearly half of the IOPC’s senior investigating staff are themselves former police officers; 40% of them as of 2019.

Many impacted families who’ve lost loved ones to police killings and their advocates question whether the IOPC is truly independent of the police forces it is supposed to monitor.

INQUEST released a survey in February 2023, saying their research found that Black people are seven times more likely to die than white people following the use of restraint in police custody or following contact. The survey condemns that despite this evident racial disproportionality, none of the accountability processes through the IOPC effectively and substantially consider the role racism might have played in these deaths.

These are some of the results of the survey:

- Not a single officer had a case filed against him for racial discrimination between 2015 to 2021.

- There have been no findings of misconduct or gross misconduct for discrimination on the grounds of race against the officers involved.

- No police officer was referred to the Crown Prosecution Service for racially aggravated charging.

- Coroners are unwilling to allow a wider discussion about discrimination in relation to the circumstances of deaths.

These findings contradict the official narrative on institutional racism within the Metropolitan Police as expressed for example by Cressida Dick, New Scotland Yard chief. Dick stated in July 2019: “The label [of institutional racism] now does more harm than good, it is something that is immediately interpreted by anyone who hears it as not institutional but racist – full of racists full stop, which we are not. It is a label that puts people off from engaging with the police. It stops people wanting to give us intelligence, evidence, come and join us, work with us.”

INQUEST describes in the conclusion how this affects families seeking justice:

“The absence of race in inquests examining police restraint-related deaths of Black men means the process does not fulfil their objective of establishing what happened in such cases. Instead, bereaved families are left feeling that police misdeeds have gone unpunished; that lethal malpractice will continue, and shameful conduct is never publicly acknowledged. Without significant consequences over the years, families conclude that investigatory processes are designed to protect the police, not to deliver justice.”

‘There is no justice, there is just us’ – Marcia Rigg

The tension between the police and BME communities is long-standing. Racist anti-Black policing has a long-history in London and accompanies neoliberal development plans that lead to gentrification of Black and multi-ethnic neighborhoods.

The shooting of Chris Kaba has direct parallels to the fatal shooting of Mark Duggan in 2011. Both are Black men. Both were subjected to a “hard stop” and then shot by police. Both were unarmed when they were shot. Both had their character assassinated by the local police and media who victim blamed them and criminalized them after they were killed. One of the biggest riots in UK history, the London Riots, followed Duggan’s killing.

With both the internal and external police accountability structures failing to produce consequences for police officers, impacted families have repeatedly said they’ve lost faith in the British state in their fight for truth and justice. After their loved ones are killed, families face multiple stages of re-traumatisation in their unequal battle against the state.

Nevertheless, while their wound is open and bleeding, some impacted families, like the family of Chris Kaba, find reserves of courage and strength to fight for the memory and justice for their loved ones. This is the reality in England for Black and minority ethnic (BME) communities.

A large ecosystem of community organizations has been developed along with victim support campaigns, networks to monitor racist police violence, mental health support for families, legal services for victims of in-custody deaths. At the center and at the forefront of this ocean of community resistance are the families of the victims.

Leading the way among many others is the United Friends and Family Campaign (UFFC), a coalition of those affected by deaths in police, prison and psychiatric custody. Founded in 1997 as a network of Black families, UFFC has expanded to include people from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds affected by these killings As it has every year since 1999, on October 29, 2023, UFFC will hold its annual procession to remember their loved ones who have been killed by police.

The British Thin Blue Line

Similar to the U.S., police in the U.K. put a thin blue line in the middle of their flag and use the insignia on social media platforms as a form of unity with police forces. Over the last decade, the symbol has been widely commodified into merchandise and sold for profit by police charities and foundations worldwide.

The term “thin blue line,” according to Black Lives Matter UK, is a police reference to “a line which keeps society from descending into violent chaos. Colloquially, the term also refers to the idea of a code of silence among police officers used to cover up police misconduct. The code of silence follows being branded as a traitor or an outcast within the unit or service and would frown on whistle blowers.”

Earlier this year, in July 2023, Met Police Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley banned officers from wearing the thin blue line badge, prompting backlash from police and their families.

From the very beginning of the Chris Kaba case, the thin blue line was at work. London Metropolitan Police officers were quick to lobby, express their concerns and leak to the media about how a proposed charge against their colleague would negatively affect them.

Immediately after Kaba’s killing, the Metropolitan Police Federation said it “supports a brave firearms colleague involved in a recent incident in south London. And we also support his family. Our thoughts are with all those affected.”

Following the suspension of Officer NX121 in the opening of the IOPC homicide investigation, police units came out in support of their colleague and threatened to hand in their weapons.

After the Crown Prosecution Service announced on Sept. 20, 2023, that the Metropolitan Police officer who shot Kaba was charged with murder, a number of police officers stopped their armed duties in protest. More than 100 officers handed in the so-called ticket allowing them to carry firearms, expressing concerns that they will face years of legal action for adhering to the tactics they learned and the training they were given.

Officers are prevented from striking in London, despite this, there was a de facto strike in the ranks of the London Metropolitan Police. These actions forced New Scotland Yard to call in additional police officers from neighboring police forces.

The Metropolitan Police denied recent media reports that Met firearms officers had resigned from their posts, saying most of them had returned. Pressure from within police ranks still appears to be strong with recent media reports citing the willingness of “thousands” of firearms officers to hand in their weapons if the order to not name Officer NX121 is lifted by the court.

At the officer’s first court appearance facing a murder charge on Sept. 21, 2023, District Judge Nina Tempia banned any publication identifying the officer, granted him bail and took his passport with orders to not leave the country.

Assistant Commissioner Matt Twist has released the following statement prior to the next stage in the legal process following the CPS decision to charge firearms officer NX121 with the murder of Chris Kaba. pic.twitter.com/BLMLFabwMj

— Metropolitan Police (@metpoliceuk) October 4, 2023

According to the BBC, a plea and trial prep hearing are scheduled for Dec. 1 with a possible trial date of Sept. 9, 2024.

Related Coverage from Europe:

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: