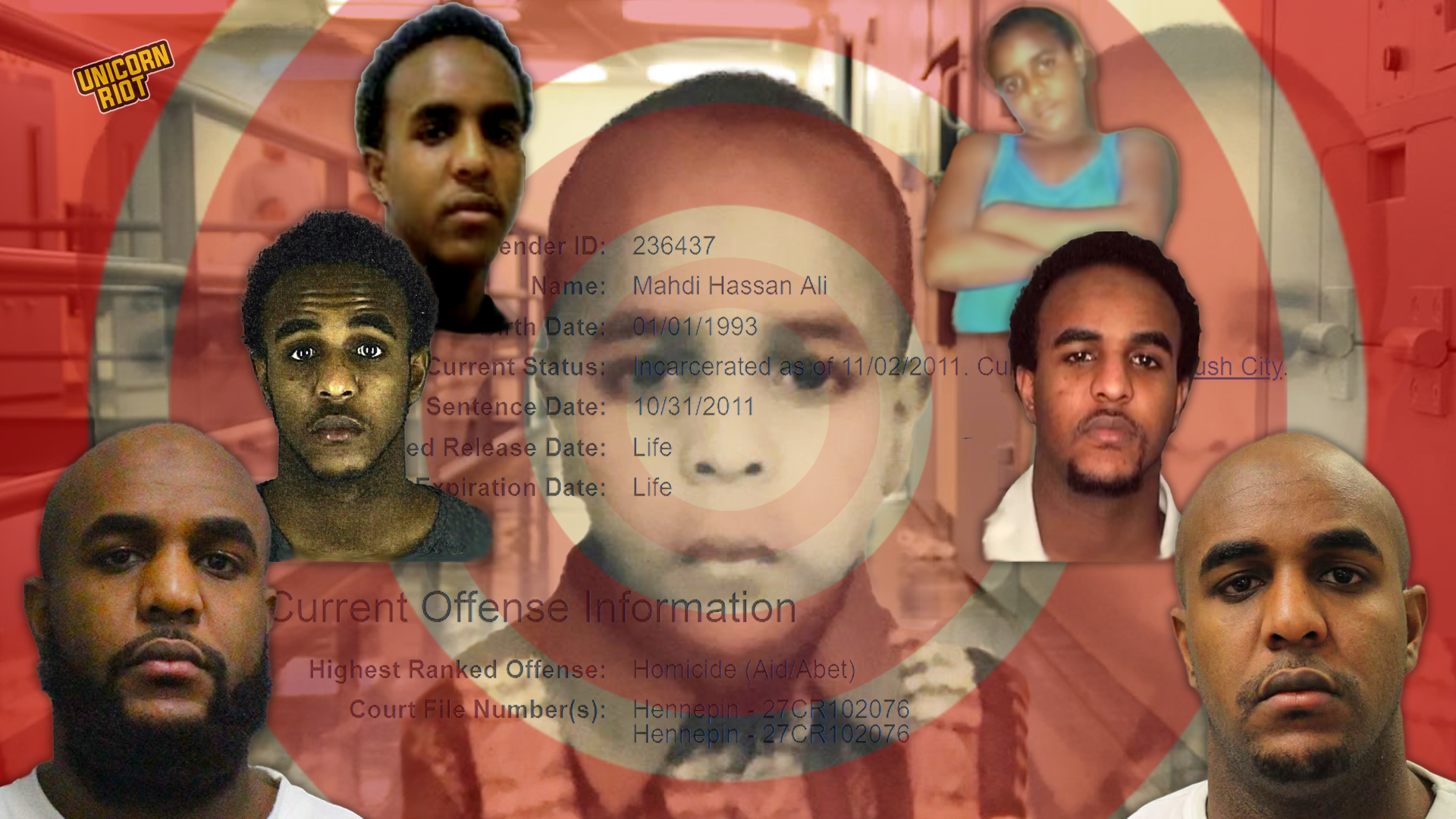

Target, ‘Junk Science’ and Unreliable Testimonies: The Contentious Conviction of 15-Year-Old Mahdi Ali

Part 12 in the series: 21st Century Jim Crow in the North Star City

Minneapolis, MN — Overlooked details have emerged casting serious doubt on Mahdi Hassan Ali’s conviction for a 2010 triple murder, as well as the integrity of the investigation by the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) and the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office.

“I was the perfect scapegoat.”

Mahdi Hassan Ali

Part 12 – The final installation in the series: 21st Century Jim Crow in the North Star City

The remarkable story of Mahdi Ali, who is serving a life sentence for a triple murder that he says he didn’t commit, was once compared to a Charles Dickens novel. His supporters say he is provably innocent.

Unicorn Riot’s independent investigation of his arrest and prosecution found dozens of issues in the case and found that his conviction was largely based on unreliable testimonies from two people implicated in the crimes, along with the multinational retail giant Target Corp’s forensics team, who testified at trial against the teen.

Ahmed Shire Ali, the accomplice in the crimes, served 12 years in prison and testified against Mahdi, but before he was released from prison he recanted his claims of Mahdi’s involvement. “I was protecting someone else. And he (Mahdi) ended up taking the fall for something he didn’t end up doing.”

Editor’s notes: 1. When referring to the three suspects in this report, we use their respective first names to avoid confusion. 2. Documents’ page numbers refer to case file pages indexed in the “Case Documents” section. Refer there to see which pages are located in each PDF file.

Interview: Breaking Down the Mahdi Ali Case

Marjaan Sirdar breaks down the major elements people should know about this contentious case.

Content advisory: the following section details violent acts.

On the night of January 6, 2010, within 62 seconds of sheer horror, three men, Anwar Mohammed, Mohamed Warfa and Osman Elmi, were slain at the Seward Market in South Minneapolis during a robbery that went wrong.

At 7:43 p.m., two masked suspects entered the market. The first suspect pointed a gun at the two men working near the cash register, Osman Elmi and Mohamed Warfa, and demanded the money, while the second unarmed suspect ran to the back of the store where he attempted to subdue the two customers inside the market.

Thirty seconds into the robbery, a customer, Anwar Mohammed, walked into the store startling the gunman, who turned around and shot him. Elmi and Warfa rushed the gunman from behind as he attempted to flee. That’s when he turned back around and shot Warfa, leaving his body in the doorway, as he fled the store. The second suspect followed the gunman out of the store as soon as he heard the shots. Elmi pulled out his cell phone appearing to call for help; seconds later the gunman returned and chased him to the back of the store and shot him three times in the back. On his way out, the gunman shot Anwar Mohammed again, who was apparently still alive.

Three people were gruesomely killed in a botched robbery which was captured on surveillance video.

The Fallout

Within the first 48 hours of the murders, police positively identified one of the suspects as 17-year-old Ahmed Shire Ali (p. 100). He later pleaded guilty to three counts of aggravated robbery and received a 12-18 year sentence.

Charged with being the shooter, Mahdi Ali, who was just 15 years old at the time of the killings, denied any involvement and pleaded not guilty. He was tried as an adult and convicted September 23, 2011 for one count of premeditated first-degree murder, two counts of second degree murder, and three counts of first-degree felony murder. Mahdi Ali was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole (p. 2052-2053). He is currently in MCF-Rush City.

For more than 14 years, Mahdi has ardently maintained his innocence. He believes Ahmed committed the crimes with his cousin and had every reason to frame him.

In 2013, Mahdi unsuccessfully appealed his sentence at the Minnesota Supreme Court, which ruled against him the following year, but he continues to fight for his freedom to this day.

An Extraordinary Story

Mahdi said growing up in the system and having a guardian who was illiterate and didn’t speak English made him an easy target for police to pin the murders on. “I was the perfect scapegoat,” he exclaimed.

Mahdi’s life story is something movies are made out of. He told Unicorn Riot his real name is Khalid Farrah and the couple that brought him to the U.S. from a refugee camp in Kenya when he was 9 years old were not his real parents. They changed his name and birth date to January 1, 1993 for immigration purposes. Mahdi Ali was the name of their child who died in Kenya.

Khalid and Mahdi were friends and when his friend died, the parents offered him an opportunity to go to America, but he would have to assume the identity of their son, and keep it a secret, which he did.

Upon arriving in the U.S., the couple separated and abandoned Mahdi, he told UR. He ended up in and out of foster homes, group homes, and juvenile detention centers, until he was reunited with who he thought was his grandmother, after she arrived from Kenya and won custody a few years later when he was in high school.

Mahdi admitted that he wasn’t an angel. “I had to take care of myself,” he explained.

“How could they blame me for surviving when I was just a kid and they put me in that situation in the first place?” Mahdi continued to get in trouble as a teen, though he said he never carried guns and mostly got into trouble for theft and stealing cars. “But I am not a killer,” he insisted.

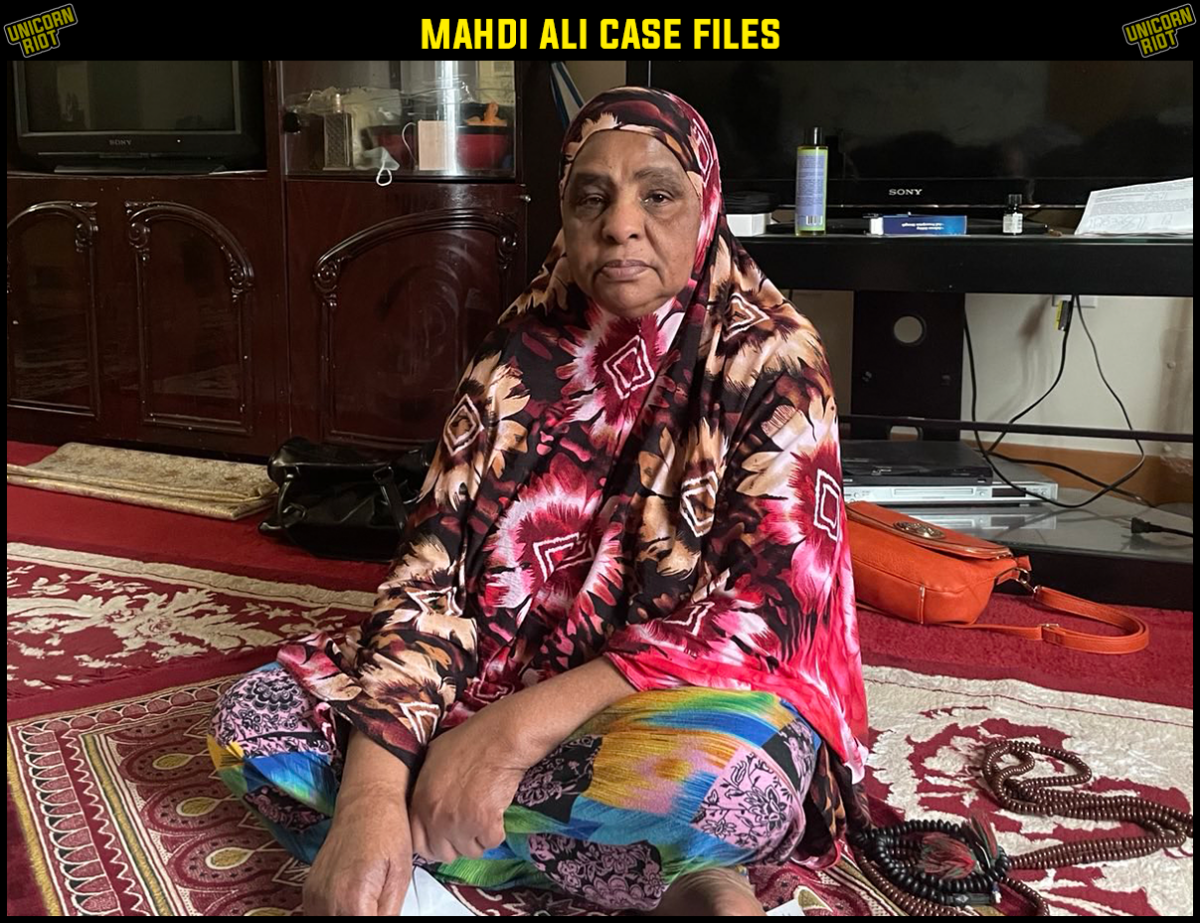

After Mahdi’s arrest, the woman he believed was his grandmother, Sainab Osman, revealed that she was really his biological mother, which was also backed up by DNA tests. Osman, with whom Mahdi shares a striking resemblance, spoke to UR through an interpreter.

She explained that she was sick and nearly died during delivery and had no choice but to give the baby over to her niece and her husband, whom Mahdi always believed were his biological parents. The couple who brought Mahdi to the U.S. were neighbors and knew his parents.

Before trial, Osman produced Khalid Farrah’s Kenyan birth certificate stating that he was actually born on August 25, 1994, in Nairobi, making him 15 years old at the time of the murders, requiring his case to remain in juvenile court. But Hennepin County Judge Peter Cahill rejected the document and instead allowed the state to have a dentist examine the teen’s teeth, a practice that is widely criticized as questionable science. The state’s witness testified that his teeth made him at least 17 years old, allowing the state to try him as an adult.

Osman said that she has always believed in her son’s innocence. “There’s no way I would’ve thought that he was involved,” she explained, adding, “the family supports him and we all want him home.”

Renewed Interest in the Case

The case was featured on See No Evil, a true-crime TV show based on solving cases using surveillance video forensics. An episode called “Too Much Video” aired in February. Two retired detectives who led the investigation for the MPD, Ann Kjos and Luis Porras, as well as then-county prosecutor Chris Weber, retell their versions of events surrounding the Seward Market murders. The program revealed that the same two suspects stopped at the Dahabshiil check cashing store at Franklin and Nicollet Avenues more than an hour before the murders, in what they reported was an apparent attempt to rob it before abandoning the plan. Unsurprisingly, the show portrayed the young Mahdi Ali as a cold-blooded killer and the case was closed, as far as they were concerned.

However, Unicorn Riot’s investigation found that it’s not so simple. UR reviewed more than two thousand pages of documents, including the police report, trial transcripts, news reports and other legal documents. We conducted numerous phone interviews with Mahdi from prison, interviewed Mahdi’s mother, his friend he was with the night of the killings and several other sources, as well as reviewed parts of surveillance footage related to the crimes, all creating a very different version of events than the official account.

This report documents nearly thirty issues we found in the official investigation of the Seward Market murders, from minor to major — detailing unethical practices used by police and prosecutors including the use of a paid informant and a jailhouse snitch, circumstantial evidence that points to other suspects, and the statement from Ahmed Ali that he lied about Mahdi’s involvement — all showcasing a fixation by authorities to convict Mahdi while the evidence suggests that the real killer escaped accountability.

Mahdi Ali case documents (PDFs):

- Minneapolis Police Report:

- Trial Transcripts from September 2011:

- Sentencing Hearing Transcript: 10-31-2011

- Appeals Court Ruling [Oct. 2014]

Unicorn Riot redacted witnesses’ personal information from police reports.

This investigation covers 27 separate issues. As options for the reader’s preference, page through the timeline-style collection below, or underneath the collection, click the right-arrows to reveal issue details within the story page. The text in each display is the same but some image placements are different; there are no links in the collection.

Issue #1: Two Cousins Turned On Mahdi

Ahmed Ali was initially charged with six counts of murder (p. 1156) including three charges of first-degree premeditated murder, and was facing life in prison (p. 1143), according to the trial transcripts. But instead, Ahmed blamed Mahdi for the murders after receiving a deal from prosecutors. Ahmed pled guilty to three counts of attempted aggravated robbery and received a reduced sentence of 18 years in exchange for testifying against his friend. Former prosecutor Chris Weber told See No Evil: “Often, we wouldn’t make such an offer but there was pressure from the community.”

It should be noted that the judge did not allow Mahdi’s murder trial jury to hear that Ahmed had a life sentence hanging over his head before he agreed to testify against Mahdi in exchange for a reduced sentence (p. 1147).

There is speculation that Ahmed Ali’s cousin Abdisalan Ali, who also testified in the trial against Mahdi, did so in exchange for not being charged with a crime. He was the only one of the three teens who got off, yet much of the evidence and witness statements pointed to him as being the killer. Mahdi is not related to Ahmed nor Abdisalan, although they have the same last name.

The day after Mahdi was convicted, Abdisalan appeared to brag on X (formerly Twitter) about killing people, among dozens of other posts about guns and violent rap lyrics. Interestingly, Abdisalan told the detectives during one of his interviews that he wanted to be a cop (p. 245). According to community members, Ahmed Ali and Abdisalan Ali moved to Dallas, Texas. Abdisalan’s X page seems to confirm that he was in Dallas in the years following Mahdi’s trial. Unicorn Riot has been unsuccessful in tracking down either of the cousins for a response to this story.

Issue #2: Mahdi Claimed He Had an Alibi

Mahdi confirmed that he was with Ahmed and Abdisalan earlier that day. He told Unicorn Riot he picked up the cousins from school around 4:30 p.m. on January 6, 2010, and drove to SuperAmerica gas station on 22nd St. and Lyndale Ave. S., Wilsons Leather Coat Outlet Store on Glenwood Ave. N., and the city impound lot next door where he unsuccessfully tried to retrieve his car because he was short $20, he explained. All of the stops were confirmed by surveillance videos except the coat store. Mahdi said he then dropped both cousins off at Abdisalan’s house near Lake St. and drove around until it was time to pick up his friend whose red Crown Victoria he was driving.

Mahdi’s friend A.J., who asked to be referred to by a pseudonym in this report, confirmed to detectives that Mahdi was driving his car and had picked him up from work at the time of the killings.

Although some details are a little fuzzy, both Mahdi and A.J.’s stories are consistent with one another: they picked up another friend and drove to Wells Fargo Bank near Mahdi’s home so A.J. could get money out of the ATM, they drove to Brooklyn Center to buy some cannabis, stopped at a gas station, parked, smoked, then drove back to South Minneapolis to Mahdi’s apartment where he got dropped off. Mahdi recalled a large police presence and several neighbors gathered in front of his building. When he walked inside, he learned from a neighbor about the killings. According to the police report (p. 88), detectives spoke with the manager of Nutrition Services at Fairview Riverside Hospital, where A.J. worked, who confirmed that he clocked out at 7:36 p.m. on the evening in question. A.J. told Unicorn Riot he waited no more than 15 minutes for Mahdi to pick him up. But according to the police report, A.J. told them he used the library and didn’t leave the building until 8:15 p.m.

A.J. said he trusted Mahdi with his car because Mahdi had been responsible in the past. A.J. was adamant that police lied.

“I know for a fact I didn’t wait an hour because I would have been angry. That would have been a violation of our agreement. I waited 10 minutes, 15 max,” he insisted.

Mahdi told UR that he picked up A.J. around 7:45 p.m., but certainly no later than 8 p.m., making it impossible for him to commit the murders. The problem was, Mahdi did not originally tell investigators the truth about where he was, which gave them a reason to make him a suspect.

He admitted it was a mistake, but said he was only a kid at the time and just wanted to go home. “It was late at night and I was just telling them anything I could think of to get out of there. That’s the truth!”

Mahdi became emotional: “I never thought I’d be incarcerated for a crime I didn’t commit.”

A.J. was adamant about Mahdi’s innocence and rejected the notion that his friend would commit a triple murder and then pick him up and behave completely normal. A.J. is still employed at the hospital more than 14 years later.

Issue #3: Mahdi Believes Police Manipulated the Report

According to the police report, detectives say they were able to confirm surveillance video from the hospital with A.J.’s pick up time at around 8:30 p.m. rather than 7:45 p.m. like he maintains (pp. 88, 260). Cops timed themselves driving the route that Ahmed said they took after the killings and argued that the extra 45 minutes allowed Mahdi to commit the crimes and still pick up his friend. But A.J. and Mahdi remain steadfast that the police lied and manipulated the report.

Issue #4: Key Surveillance Footage Never Secured

Mahdi said surveillance video from the hospital confirming his alibi was never turned over to his attorney or introduced during the trial. Detectives never recovered the video from the hospital, only still images were requested, according to Detective Kjos (p. 88). Instead, a security guard from the hospital testified at trial that he reviewed the hospital surveillance videos from the night of the killings and it matched the cops’ narrative, that A.J. was picked up at 8:26 p.m. — not 7:45 p.m. Although the guard acknowledged in court that the time in the video was off 15-20 minutes (p. 1580). Mahdi believes it was all too convenient for the police.

Surveillance footage from Wells Fargo of A.J. getting money out of the ATM was never secured or even mentioned by the investigators. Neither was the surveillance video from the AutoZone car parts store on Lake St. next to Abdisalan’s house, which could have verified Mahdi’s claims that he dropped the cousins off after their trip to the impound lot.

Issue #5: Excluded Interviews

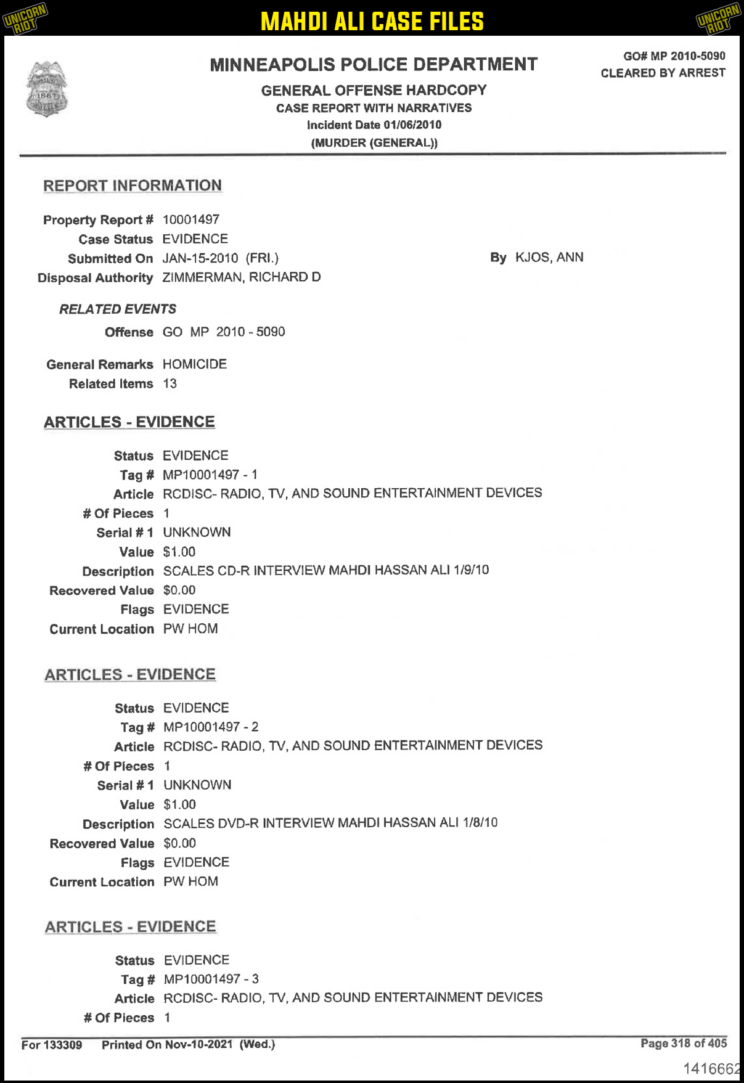

Recordings from police interviews with suspects and informants are listed on the police report inventory (pp. 318-319) but were never introduced in court; only transcriptions of those interviews were shown. The transcripts from Mahdi’s and Ahmed’s numerous interviews with detectives, however, are excluded from the police report that Unicorn Riot obtained, and instead police provided their own summaries of the meetings.

Issue #6: Height Contradiction

Although prosecutors argued that “the shooter appears to be much shorter than the person who goes to the back of the store,” (p. 740) it was never credibly established that the killer in the video was indeed shorter than the accomplice. Mahdi was nearly a half foot shorter than both Ahmed and Abdisalan. Mahdi was listed as 5 feet 8 inches tall in the police report although he told UR he was really 5 feet 7 inches at the time.

Ahmed Ali, who was positively identified as the accomplice in the surveillance video from the Seward Market, was listed as 6 feet 1 inches in the report. Court records from 2013 also confirm Abdisalan’s height as 6 feet 1 inches.

An elderly Somali man, who was one of the customers in the store that night, testified in court through an interpreter that the shooter was shorter than his accomplice, but he could not say by how much (p. 947). According to the surveillance video, the elderly man did not appear to be in a vantage point to see the shooter and accomplice standing next to one another.

Abdisalan testified in court that Ahmed was about a half-inch taller than him when the murders occurred (p. 982). Ahmed also had a big afro at the time, which would have made him appear even taller.

Issue #7: Target’s Scientific Racism

For years, Target investigators have worked alongside local, state and federal law enforcement in criminal cases that go far beyond shoplifting. Unicorn Riot’s years-long investigative series has reported on the rise of Target’s public-private partnership, divulging its financial ties with the City of Minneapolis and Hennepin County. Findings in this series illustrate that neither MPD nor the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office have demonstrated independence from its corporate funder and have essentially served as “hired guns” for the retailer, operating a racialized surveillance program that has helped roll back civil rights on Black residents and is at the core of this reporting.

Two members from Target’s forensics team assisted police with the investigation and testified against Mahdi, including James Schoering, who left the retailer to work for the FBI. (Schoering was no longer working for Target at the time of his testimony, but was testifying on their behalf, not on behalf of the FBI). He claimed that the gunman in the video was shorter than the man who entered the store after him, but never specified by how much (p. 1304). Schoering also admitted under cross-examination that he could not positively identify Mahdi in the surveillance videos, nor could he exclude Mahdi or Abdisalan as suspects (pp. 1328-1331), although there is nearly a half-foot height difference between them.

After the trial, Target Forensics Specialist Jake Steinhour described to MPR News the process of “ghosting images,” which takes several images or video sources and creates a composite image or video; a technique Target forensics team utilizes during its investigations. He took the stand at Mahdi’s trial claiming that the jeans worn by the killer in the video appeared to be similar to the jeans MPD recovered in Ali’s home. This was never credibly established as factual during the trial. Under cross-examination, Steinhour said he could not positively identify the jeans found in Mahdi’s home as the jeans on the surveillance video, nor could he exclude them (pp. 1492, 1494).

Mahdi’s supporters believe Target’s testimony was based on questionable science and it was really the corporate giant’s credibility that swayed jurors and moved the court.

Michelle Gross, a paralegal who works for Mahdi’s post-conviction attorney Zorislav Leyderman, told Unicorn Riot, “Clothing mark analysis in mass-produced articles of clothing such as jeans has no legitimate basis and should never be used to deprive someone of their freedom. It is junk science, plain and simple.”

Although no scientific conclusions were established with their testimonies, the Minnesota Supreme Court heavily cited Target’s forensics team in its ruling striking down Mahdi’s appeal.

Mike Freeman, then-Hennepin County Attorney, and the prosecutors who worked on this case never disclosed the office’s partnership with Target at Mahdi’s trial. Only after Mahdi’s attorney unearthed the multinational corporation’s funding to the county attorney’s office did the jury hear about this relationship (p. 1319).

However, it was never revealed in court the extent of how much Target has helped reshape Minnesota’s criminal justice system by not just funding the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office, but also funding the Minneapolis City Attorney’s Office and the Minneapolis Police. The judge that presided over Mahdi’s trial, Peter Cahill, worked for the Target-funded Hennepin County Attorney’s Office before being appointed to the bench. The current Chief Judge of the Minnesota Court of Appeals, Susan Segal, previously served as the Minneapolis City Attorney whose office was funded by Target and its subsidiaries.

Target does not offer its forensics services to defendants, only to prosecutors (p. 1319).

Issue #8: Mahdi Insists Police Planted Blood Drop

Detectives alleged that they found a small blood stain from one of the victims on Mahdi’s jeans that were seized during MPD’s raid at his apartment. The blood evidence was contaminated with the DNA of three other people (p. 1834), however, including a state investigator. Mahdi insists the blood drop was planted. He said it was not a coincidence that MPD did not discover that blood until months after they recovered the jeans in question (p. 143).

“How else do you explain them finding blood inside the pocket but nowhere else? Not on any of my clothes or shoes or inside the car I was driving that night. That don’t make no sense,” he said, considering how bloody the crime scene was.

“Why would I get rid of all the other clothes but keep the jeans?” he argued.

Issue #9: No Evidence Found in Alleged Getaway Car

Prosecutors and police maintained that it was the red Crown Victoria that was used as the getaway vehicle after the killings. Yet, A.J. told Unicorn Riot that he got his car back the day after his interview with detectives on January 13, a week after the murders. Police did not find any evidence inside the vehicle linking it to the crimes. Mahdi believes that if the car was really involved in the crimes, then police would have kept it much longer, which is standard practice.

Issue #10: Adbisalan’s Friend Told MPD He Confessed to the Killings

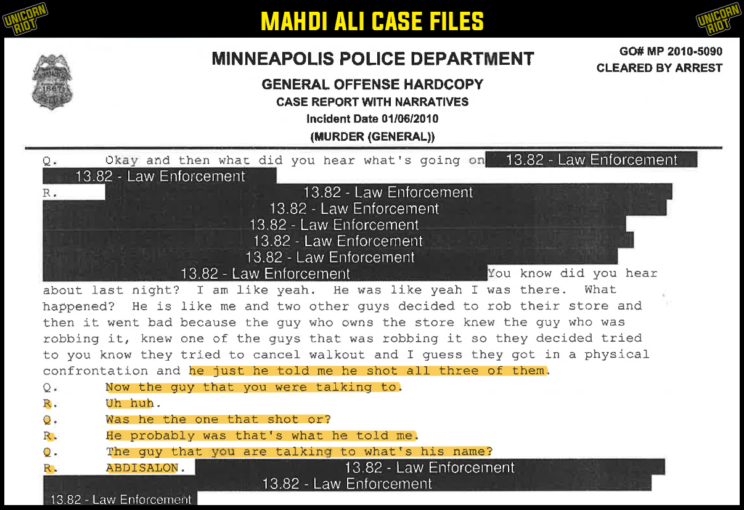

Abshir Asse, who is referred to as a “concerned citizen” and a classmate of Ahmed and Abdisalan in the report, went to the police after the killings and initially named Abdisalan Ali as the gunman. Asse’s name on the police report is redacted except where MPD mistakenly forgot to hide his identity. He said Abdisalan told him all about what happened the next day at school, implicating himself in the killings and Mahdi as his accomplice (p. 97).

According to the report, “this concerned citizen gave details about the events during the murders that only persons involved in the murders could possibly know” (p. 47). Abdisalan told his classmate that he took the gun off safety and shot a customer that walked through the door during the robbery and on his way out of the market, he had to step over two dead bodies. Asse explained, “he told me he shot all three of them” (p. 97).

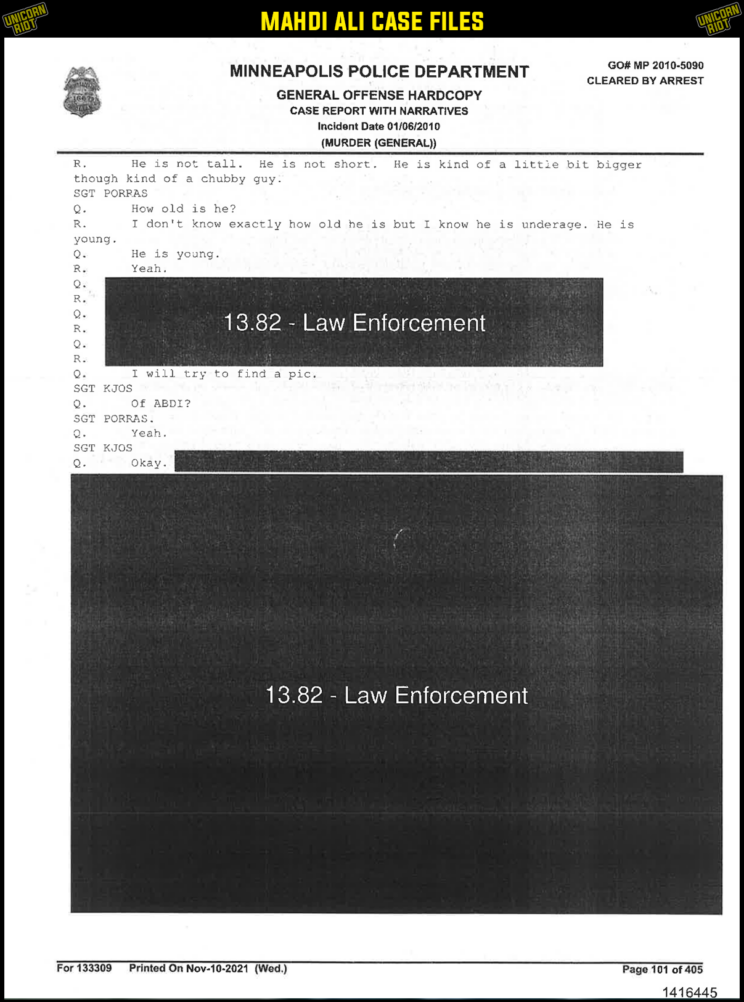

Detectives showed him surveillance footage of the two boys talking at school. “The guy that you are talking to,” Detective Porras asked, “What’s his name?” Asse confirmed it was Abdisalan. Yet, key paragraphs from this interview were redacted where the informant began providing details, hiding important information about the crimes (p. 97).

Issue #11: Second Informant Fingered Abdisalan

At one point during Abshir’s interview, detectives asked him to call his friend Mohamed Farrah to obtain information about the suspects. Farrah, who reported information about the suspects online the day after the murders implicating the two cousins (pp. 97-98), gave him Abdisalan’s address. Before ending the call, Asse asked Farrah if he knew Mahdi’s last name to which he replied, “No, I do not know his name at all.”

On June 14, 2010, detectives interviewed Mohamed Farrah. He acknowledged that he sent the information and repeated in person what he had shared electronically in a Crime Stoppers’ tip: that Abdisalan Ali and his cousin Ahmed Ali committed the crimes. He included Abdisalan’s address. “[T]he type of offense is triple homicide and your notes are … ‘he is running around bragging about it and plans to leave the country’. Is that correct?” detectives asked. Farrah responded affirmatively. They then asked him how he learned this information, but the three paragraphs where he answered them were redacted on pages 182 and 183 of the police report.

Issue #12: Evolving Accusations

After Abshir Asse ended the call with Farrah during his first interview, police asked him again if Abdisalan was the gunman, in which he inexplicably changed his story, now saying Mahdi was the shooter (p. 100). Two pages in the interview, pages 101 and 102, are redacted by detectives, potentially hiding crucial details in the case.

During Farrah’s June interview, his story suspiciously changed following three redacted paragraphs. He now said Mahdi and Abdisalan were both the killers (p. 183).

Issue #13: Abdisalan Implicated Ahmed As He Hid

Detectives found out that Ahmed was on the run from the police. When they interviewed Abdisalan they asked him why Ahmed was hiding out and the first thing he did was implicate his cousin in the killings: “[H]e’s probably hiding because he knows that he committed a crime. … That murder stuff that happened” (p. 200).

Issue #14: Abdisalan Didn’t Like Mahdi, Had Motive to Frame Him

Shortly after naming his cousin, Abdisalan put Mahdi at the crime scene with him, and a few minutes after that, revealed that he and Mahdi didn’t get along (p. 115).

This proved important later for the defense during the trial when Mahdi’s attorney confronted Abdisalan. He asked him if he and Mahdi got along. Abdisalan initially lied and said that they did. After being pressed by counsel, he admitted, “I mean, I probably didn’t get along with him, we probably fought a couple of times, it’s not that I hated him or anything” (p. 1009).

Abshir Asse, Abdisalan’s classmate, also told police that he and his friend Mohamed Farrah had reason to believe the cousins were trying to frame Mahdi (p. 97). This is among other evidence implicating Abdisalan in the killings that were seemingly disregarded by detectives.

Issue #15: Abdisalan Threatened Mahdi

According to the police report, Abdisalan told his classmate he was going to silence Mahdi. Asse disclosed: “He… said that he was going to try to go kill Mahdi,” adding, “So to cover everything up. He thinks that Mahdi will tell on him” (p. 104). This is inconsistent with Mahdi being the killer and having the most to lose. The next paragraph in the interview was redacted by the police.

Mohamed Farrah, who sent in the Crime Stoppers’ tip accusing Abdisalan and Ahmed of the crimes, also confirmed to detectives that Abdisalan threatened to kill Mahdi to silence him so he can protect him and his cousin (p.184). Mahdi confirmed to UR that he also heard this rumor in the community the day after the killings.

Issue #16: Abdisalan Talks ‘Killings and Stuff’ at School

Detectives showed Abdisalan surveillance footage of him and Abshir Asse talking at school on January 7, the day after the murders, and asked him what they were talking about. He said they were talking about the “killings and stuff,” but said he was referring to battles back home in Somalia. (Heavy fighting in Somalia did occur on January 10, 2010, three days after Abdisalan talked to his classmate and a day before the interview). Apparently this didn’t raise red flags for detectives, despite Asse’s claims during his interview on January 8 that Abdisalan was really talking about how he killed three people at the Seward Market the night before (p. 97).

Issue #17: Cop Coercion

The cops seemingly coerced Abdisalan after he began having second thoughts about answering their questions and tried to end the interview. “I need you to give me this interview,” Detective Kjos pleaded (p. 110). Moments later her phone rang, “Hold on a minute.” She answered the call. After hanging up, she told Abdisalan, “We know who did it and they’re in jail right now” (p. 111). She told him she just needed him to corroborate the events that happened earlier that day before the killings, to which he agreed.

Issue #18: Abdisalan Offers Up His Cousin

Early on in the investigation, detectives requested Abdisalan’s help in tracking down his cousin after he allegedly fled to Canada. “If the people are already talking about him [Ahmed] and Mahdi being involved,” Detective Porras said, “you know not everybody is [as] calm about the thing as you are,” appearing to suggest their willingness to downplay his alleged involvement in exchange for his assistance. According to the transcripts, that’s when Abdisalan promised to look for and turn over his cousin (p. 202).

Issue #19: Did Abdisalan Receive A Secret Deal?

On January 11, during his second interview at MPD headquarters, Abdisalan implied that detectives had already cleared him of the crimes: “the investigators … you all said now I am clean, right? I can say whatever and do whatever, right?” (p. 247).

From the jump, detectives made him aware that his third interview on January 13 wasn’t an interrogation and they were simply taking a statement from him as a witness who was with the suspects earlier in the day. “We have no evidence to show you were at the scene when this thing went down,” Kjos said. “So… what I’m asking you is not up at the scene. I won’t ask you any of that because you went home. Right?” (p. 108).

Prosecutors even acknowledged in court that after Abdisalan’s first interview, “investigators concluded that he had not been in the market at the time of the murders,” and from that point on they focused on confirming Abdisalan’s story and made Mahdi Ali their main suspect (p. 741).

Despite investigators clearing Abdisalan’s alibi, the previously stated evidence and witness statements lead to speculation that Abdisalan wasn’t charged in exchange for testifying against Mahdi.

Issue #20: Abdisalan’s Alleged Alibi

Abdisalan told police that he and his cousin Ahmed drove around with Mahdi for a while, made a few stops, including the Dahabshiil check cashing store, placing himself at the scene where surveillance showed the same two suspects from the Seward Market apparently casing the place. However, Abdisalan said it was Mahdi and Ahmed who went inside while he stayed in the car. Mahdi denies ever going there.

Abdisalan said Mahdi then dropped him off at home by 6:40 p.m. Before he departed, he claims that he pleaded with his older cousin to go home, saying, “Just don’t do no stupid stuff,” because he didn’t trust Mahdi (p. 248). According to him, he told Mahdi to take Ahmed home, then went inside to his room and went straight to sleep. He repeated his claim on the witness stand – that he went home and went to sleep – although he said the sun hadn’t even gone down yet, which was provably false (p. 993).

However, according to Mahdi’s attorney, Abdisalan’s cell phone data proved that he wasn’t at home at 7:04 p.m. when he made a call to Ahmed’s brother, but rather his phone pinged on a tower north of his home, which is in the direction of the Seward Market (p. 2001). Unicorn Riot has not been able to secure Abdisalan’s cell phone records to verify these claims.

Issue #21: An Unserious Investigation

At one point during his interview, detectives seemed to run out of patience with Abdisalan. Detective Kjos turned up the pressure, “Your name came up right away” (p. 246). Porras said, “There’s something not right here.” Kjos echoed her partner. “Somehow, some way somebody was given specific details about what happened inside that convenience store. Details only either the person who was in there or at least somebody who was in there told them what happened” (p. 247).

Porras reminded Abdisalan how helpful he had been but warned him that if he was lying he could be charged not with murder but with obstructing a murder investigation (p. 247).

According to police transcript time stamps, Abdisalan’s first interview was rather short for a murder investigation (p. 200) and throughout all three of his interviews, detectives never once asked him if he killed those three people, or if he was involved in the crimes. Abdisalan was never charged with any crime related to this case.

Issue #22: Abdisalan Implicated in Another Killing

Shortly before Abdisalan’s classmate’s interview with police ended, he dropped a bombshell on detectives. Abshir Asse implicated Abdisalan in another murder: “It was a thing … a killing in Apple Valley. I don’t know exactly when this was.” Detectives confirmed that a cab driver was killed in August 2009. “Someone got stabbed to death,” he continued, “and I think you have someone in custody already,” adding, “and that Abdisalan kid was with that guy that day” (p. 107). These vital details never made their way into any news reports at the time, nor were they mentioned during the murder trial.

Abdirahman Abdikarim, who was convicted for murdering the cab driver in Apple Valley, was incarcerated with Mahdi at Minnesota’s Oak Park Heights maximum security prison. Mahdi said Abdikarim confided in him that Abdisalan was indeed involved in his case but did not provide any details.

Issue #23: Ahmed’s Brother Had Stolen Gun Connected to Murder Weapon

In September 2010, Ahmed’s brother Abdirahman Ali was caught by police with a stolen gun in his car that was from the same batch of guns as the Seward Market murder weapon that were stolen shortly before the killings.

Mahdi’s attorney believed Abdirahman might have been involved in a gun store robbery just weeks before the triple homicide from where the murder weapon originated, but it was never proven.

At Mahdi’s trial, Detective Kjos acknowledged phone records from the day of the murders identifying two phone calls between Abdisalan and Abdirahman within one hour of the murders (p. 1704).

In 2013, Abdirahman killed bicyclist Jessica Hanson in South Minneapolis with his car and received a sentence of three years in prison.

Issue #24: Controversial Use of Paid Informant

Mohamud Galony, who testified against Mahdi, was described at the time of the trial as an ESL (English as a Second Language) teacher’s aide and a well-respected community member. But it was revealed at trial (p. 1706) that Galony was a Confidential Reliable Informant (CRI) for MPD Officer Mohamed Abdullahi, or in other words, a paid snitch. It wasn’t disclosed by the prosecution when they put Galony on the stand, however (p. 1102). (MPD investigators and Hennepin County prosecutors have a long history of using informants, whether paid or coerced, to wrongfully convict people i.e. Myon Burrell, Marvin Haynes, etc.)

Galony said under oath that he recognized Mahdi from the community, but acknowledged he didn’t know his name until after his arrest. He explained on the witness stand how Mahdi told him two weeks prior to the murders that he was planning on robbing the market. His testimony was so full of inconsistencies that the prosecutor was allowed to show him a transcript to refresh his memory (p. 1115).

The defense pressed Galony under cross examination: “The person that you’re asking this jury to believe told you about his plan to commit crimes, serious crimes, you did not even know his name, did you?” (p. 1110). Defense counsel then asked him his clan affiliation, to which Galony argued, “Why does that matter?” He eventually admitted that he is from the same clan as Ahmed and Abdisalan, a different clan than Mahdi, and was friends with Ahmed’s older brother (p. 1112). (Somali clans are based on biological relationships which means members of the same clan are extended relatives).

During his testimony, Galony said that Mahdi used the word “mission,” implying he was going to commit a robbery (p. 1117-1118). However, Detective Kjos testified under oath that Galony never used the word mission (p. 1707), and under cross examination Galony admitted that he never said that to police. The date of his interview with detectives was May 11, more than four months after the killings, though they claim he spoke to Officer Abdullahi on the night of January 6, 2010 (p. 160). Unicorn Riot found no substantiating documents that show Galony talked to police on January 6 other than what is stated by MPD in the police report.

Mahdi told Unicorn Riot that Galony completely made his statement up. He believes Galony never spoke to police the night of the murders and that his script was manufactured by MPD only after they had their suspects in custody. He said police found an informant, after the fact, to repeat their lies in court to secure his conviction, a documented pattern by MPD.

“It doesn’t make any sense that I would rob the store across the street from my own home, and it makes even less sense that I would tell this man who I didn’t know,” Mahdi said.

UR reached out to Galony and asked him about working for the police and if he stood by his past statements. He said Mahdi wasn’t “the best kid,” but denied being an informant and suggested that we run the story without further comment.

Despite his denial, Detective Kjos acknowledged during Mahdi’s trial that Galony was a CRI (p. 1706).

In late 2008, Galony was charged with gun possession and convicted less than a year before the Seward Market murders. In 2022, he legally changed his name to Ibrahim Jamac Adan, and on his name change application he failed to disclose his gun conviction.

(Read Galony’s interview with detectives beginning on page 160 of the police report. Police redacted his name in the report except in one instance on page 162 where they seem to have left his first name written in the transcript.)

Issue #25: Use of Jailhouse Snitch

During the trial Judge Peter Cahill allowed a jailhouse snitch to testify against Mahdi. Leandro Garcia, depicted as a career criminal by the defense, was incarcerated with Mahdi at the Carver County Jail. At Mahdi’s trial, Garcia described a special relationship he had with the jailers and said that’s why he was placed in the segregated medical unit where he met Mahdi (p. 1024, p. 1060-1061).

He testified under oath that Mahdi Ali, “a complete stranger,” confessed to him about the Seward Market murders while they were watching the true crime television show, “The First 48 Hours” (p. 1028). He claimed that Mahdi had told him the gun he used was from Ahmed’s brother (p. 1069), who was arrested in 2010.

But Mahdi flat out denied saying more than two words to Garcia; he told UR that the accusation was absurd. He accused Garcia of lying in order to get out of jail or receive some sort of favor.

Issue #26: Killer Identified Wearing Abdisalan’s Coat

Abdisalan admitted on the witness stand that he committed crimes the day of the killings when Mahdi drove them to Wilsons Leather Coat Outlet Store where he stole a Sean John jacket. Investigators identified the coat the killer was wearing on the Seward Market surveillance video to match the gray coat Abdisalan was wearing earlier that day. But he claimed under oath that he gave the gray coat to Mahdi after he stole the Sean John jacket.

The prosecuting attorney, Robert Streitz, presented an image from the surveillance video of the killer to Abdisalan. Abdisalan identified the jacket as his although he said, “I can’t recognize who’s wearing [it], but I gave the jacket to Mahdi” (p. 1018).

This confession by Abdisalan, that the coat the killer was wearing belonged to him, contradicts detectives’ statements during his interview: that they did not have any evidence linking him to the crime scene (p. 108).

Mahdi denied wearing Abdisalan’s jacket and said he does not understand why anyone would believe the person wearing the coat in the surveillance video was anyone other than Abdisalan. Yet, Mahdi chose not to take the stand in his own defense.

Issue #27: Ahmed Recanted, Says Mahdi’s Innocent

Ahmed Ali’s plea deal was contingent on him telling the truth in court while testifying against Mahdi. Despite perjuring himself on the witness stand with contradicting statements, he received a “sweetheart deal” and was sentenced to 18 years and released from prison after 12 years with good time (p. 751).

In 2021, a year before his release, Ahmed told a Fox 9 news reporter that he lied against Mahdi in exchange for reduced prison time, and Mahdi is really innocent. “He ended up becoming the scapegoat, I guess.”

The real killer, he claimed, was neither Mahdi nor his cousin Abdisalan. However, Ahmed disappeared after he was released from prison and failed to follow through on signing an affidavit, which would’ve made his claim of Mahdi’s innocence binding by the law.

A Dishonorable Judge

Mahdi’s mother believes he did not receive a fair trial, stating that she was not happy with how Judge Cahill treated her son and their family.

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that it is unconstitutional to give minors life sentences without the possibility of parole and a chance at rehabilitation. When Judge Cahill was forced to re-sentence Mahdi, he gave him three consecutive life sentences (in Minnesota a life sentence is 30 years imprisonment), stating that he wanted to send a message to future generations, “no matter what the change in the law is.” He was roundly criticized by Mahdi’s supporters for undermining the high court because the new 90 year sentence effectively keeps the 15 year old in prison for life.

Cahill was appointed to the bench in 2007 by Gov. Tim Pawlenty (R) after serving as a prosecutor in the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office under Amy Klobuchar. He presided over the murder trial of former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin, who was convicted of murdering George Floyd in 2021. Prior to that trial, Mahdi’s trial was his highest profile case.

In March, the Minnesota Supreme Court overturned a separate murder conviction based on Judge Cahill abusing his discretion by providing false instructions to the jury. In 2022, he was in the crosshairs of community activists after it was revealed that he signed MPD’s no-knock search warrant that led to the police killing of 22-year-old Amir Locke.

Ready For Redemption

Many people in Minneapolis’ Somali community aren’t sympathetic to Mahdi’s sob story. Few have been enthusiastic to support him over the past 14 years after coming to believe he was guilty. One man who went to high school with him told Unicorn Riot that Mahdi was the victim of what appeared to be a coordinated campaign against him.

During our investigation, community members (who did not want to go on record) told Unicorn Riot, based on reviewing the surveillance videos of the crimes, that they don’t believe the killer was Abdisalan or Mahdi, but instead believe the killer’s profile more closely matched Ahmed’s brother, Abdirahman, who is linked to the murder weapon.

Content advisory: the following section mentions self-harm.

Mahdi has never wavered. He has maintained his innocence for nearly half of his life that he has spent, he argues, wrongfully incarcerated. He told Unicorn Riot that he would rather kill himself than admit to a crime he didn’t commit. He disclosed that he was placed on suicide watch after his conviction. But he quickly recovered: he found God and renewed his faith in Islam. While in prison Mahdi received his GED and earned a paralegal degree. He was a model prisoner at Oak Park Heights Correctional Facility, where he was incarcerated for 10 years, according to a source who was incarcerated with him.

Another source told Unicorn Riot that fellow inmates at the Rush City Correctional Facility, where Mahdi is currently incarcerated, described him as someone who “stands out,” and is very much “a leader and a mentor” to the younger guys.

Mahdi said he would be an asset to society if he was exonerated and set free. He knows he has a lot to prove to his community and believes if granted that opportunity, he wouldn’t let the people down.

“I just wanna give back to my community and show them that I’m not the person everyone was misled to believe.”

Mahdi Ali’s family has created a new petition on Change.org to help push for a new trial and exonerate him.

Interview: Breaking Down the Mahdi Ali Case

Cover image and graphics by Niko Georgiades for Unicorn Riot.

NEW Publications

New Conviction Integrity Unit Agrees to Review Mahdi Ali’s Case – June 30, 2025

Target of Injustice: Free Mahdi Ali Campaign Kicks Off – May 12, 2025

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: