Distress Hotline Volunteer Speaks on 500+ Dead from Pylos Shipwreck

This summer, as climate disasters and human-made catastrophes compounded each other in and around Greece, one of the deadliest shipwrecks in recent history occurred off the country’s coast. The Adrianna, a boat carrying an estimated 750 migrants, capsized in the Mediterranean Sea, leaving nearly 500 people missing and presumed dead.

In the hours before the ship capsized, organizers at Alarm Phone, a self-organized hotline for refugees in distress in the Mediterranean Sea, were in contact with people on the ship. Over the course of nearly 12 hours, aid volunteers tried to coordinate with state and private ships to offer relief to those on board the Adrianna.

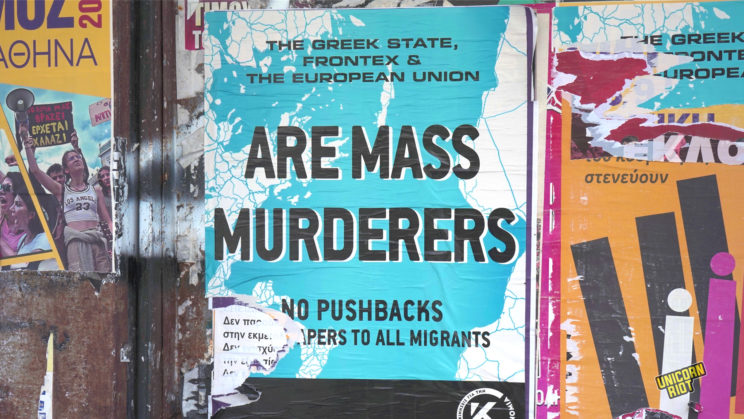

In an exclusive interview, Unicorn Riot heard from a volunteer at Alarm Phone about the deadly shipwreck off the coast of Pylos, the role of the Greek Coast Guard and the safety and rescue protocols at sea. Moreover, the general context of the anti-immigration policies of the European Union was examined along with the illegal practices of the Greek Coast Guard and deterrence policies in recent years, which have affected migration routes.

Pylos Shipwreck – Greek Seas: Europe’s Largest Migrant Cemetery – July 2023

On June 9, an overcrowded vessel named Adrianna departed from Libya set to arrive in Italy. Four days later on June 13, passengers contacted the Alarm Phone emergency hotline stating that they were in distress. In turn, Alarm Phone forwarded the location of the ship and the urgency of the situation to the Hellenic (Greek) Coast Guard and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (commonly referred as Frontex).

In the early morning hours of June 14 and over eight hours after the Greek Coast Guard was first notified, the vessel Adriana sank. According to passenger testimonies, up to 750 people were on board, most of which were migrants and refugees. The expected number of missing and presumed dead is currently around 500.

“We find it quite contradictory that during the events of the Adriana, the cameras were not working, but now, all of a sudden, the Hellenic Coast Guard is very happily “advertising” their rescues from other distress situations.”

Watch the Med Alarm Phone, or Alarm Phone for short, is a self-organized volunteer-run phone hotline for refugees and migrants who are in distress in the Mediterranean Sea. It was initiated in October 2014 by activists and civil societies in Europe and Northern Africa.

The Alarm Phone is not a rescue number, but an alarm number to support rescue operations.

“Our main goal is to offer boat people in distress an additional option to make their SOS noticeable. The Alarm Phone documents the situation, informs the coastguards, and, when necessary, mobilizes additional rescue support in real-time. This way, we can, at least to a certain extent, put pressure on the responsible rescue entities to avert push-backs and other forms of human rights violations against refugees and migrants at sea.”

Since 2014, the number of migrants recorded missing in the Mediterranean Sea is 28,089, according to the Missing Migrants Project. So far this year, an estimated 2,512 migrants have been documented dead and missing in the Mediterranean Sea by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, has recorded 178,537 sea arrivals to Italy, Greece, Spain, Cyprus and Malta this year as of Sept. 17.

INTERVIEW WITH A REPRESENTATIVE OF ALARM PHONE

Editor’s note: The following is the transcript of an interview that Unicorn Riot conducted with an anonymous representative of Alarm Phone. The name of the representative and certain portions of the interview have been redacted for security purposes.

Unicorn Riot: On June 13, you were contacted by the Adriana. What came out of your communication and what steps did you take?

Alarm Phone: In the morning of June 13, at 9:35 CEST, [Central European Summer Time] the X, formally known as Twitter user Nawal Soufi posted about a large boat in distress, carrying, according to them, 750 people. Over the following hours, Nawal Soufi adds further information, including the GPS position of the boat in distress and that authorities in Italy, Greece, and Malta have been alerted.

[The following timeline was provided by Alarm Phone]

14:17 CEST: Alarm Phone receives the first call from the boat in distress. It is difficult to communicate with the distressed. They say that they cannot survive the night, that they are in heavy distress. Alarm Phone tries to receive their current GPS coordinates in order to be able to alert authorities – but the call cuts. We try to reconnect with them.

14:30 CEST: The distressed call again, telling Alarm Phone that they would send their location. However, they do not.

15:52 CEST: The distressed called Alarm Phone twice but it was impossible to understand them.

16:04 CEST: We speak to the distressed again. They say that they would send their GPS position.

16:13 CEST: We receive the position from the people in distress: N 36 15, E 21 02. We try to gather further information but we cannot reconnect with them.

16:53 CEST: We alert the Greek authorities per email as well as other actors, including Frontex and UNHCR Greece.

17:13 CEST: We re-established contact with the people in distress. We hear “hello, hello,” then the call drops. We try to reconnect, which is not possible.

17:14 CEST: We receive a call from the boat in distress but cannot hear anything.

17:20 CEST: We speak to the distressed and they report that the boat is not moving. They say: “The captain left on a small boat. Please, any solution.” They say they need food and water.

17:34 CEST: We receive another call from the boat in distress and their updated position: N 36 18, E 21 04 – very close to the previous position. They say that the boat is overcrowded and that the boat is moving from side to side.

18:00 CEST: We call the company of the merchant vessel Lucky Sailor informing them about the boat in distress. They say that they only act under the authority of the Greek coastguards.

Over the following hours, Alarm Phone tries to re-establish contact to the distressed but either calls are not connected or it is impossible to understand one another.

20:05 CEST: Alarm Phone is informed by the distressed that they received water from the merchant vessel Lucky Sailor and that they have been in contact with the “police.” Alarm Phone also notices that a second merchant vessel, the Faithful Warrior, is close to the distressed.

Over the following hours, Alarm Phone tries to reestablish contact to the distressed but either calls are not connected or it is impossible to understand one another.

00:46 CEST on 06/14/2023: Last contact to the boat in distress. All we hear is: “Hello my friend. …. The ship you send is …” The call cuts.

UR: Survivor testimonies indicate that the boat sinking started when the Hellenic Coast Guard tried to tow the vessel. We cannot know for sure what happened there, but have you observed towings made by the Hellenic Coast Guard in the past as AP?

AP: Indeed we have observed the Greek Coast Guard using the towing method, directly or indirectly, in the past. I can recall one occasion where they had instructed a merchant vessel to tow a sailing boat towards the port of Kalamata on the Peloponnese. I can also recall another towing by the coast guard of a sailing boat in the area off Milos island. There was also another situation where, during a storm, a sailing vessel was also being towed in the area off Mykonos. The weather was very rough and reportedly, the Greek Coast Guard asset started towing the boat to some islet and it crashed onto some rocks. So, yes, we have observed towing as a way to bring the boats in distress that are immobilized to a specific location.

UR: In general, when a boat is in distress and in need of rescue, what is the operational procedure for the coast guard to follow?

AP: Well, there are safety protocols at sea in general. It’s not just the coast guards that perform rescues. It can also be other vessels. The law of the sea says that if a boat is in distress and a state authority is not there to coordinate the rescue, then nearby vessels are also obliged to provide assistance. And as we see also with the civil fleet in the central Mediterranean, the boats of the different NGOs and organizations that are rescuing migrants, the first thing to do is to stabilize the boat. Calm the passengers, distribute life jackets and once the danger has been assessed based on the state of the vessel, number of people and weather conditions, proceed with an evacuation of the vessel. Then the law requires that the people are transferred to a safe harbor to be provided with the necessary medical and psychosocial assistance.

UR: The Hellenic Coast Guard’s rescue vessels have monitoring systems, which must record every rescue operation, according to a FRONTEX directive. In the case of the Adriana vessel this did not happen, do you want to comment on this?

AP: Well, it’s quite interesting to mention that in the days following the Pylos shipwreck, the Twitter account of the Hellenic Coast Guard has posted several videos rom rescue operations, and you can tell that the cameras are on the boats, on the assets of the Hellenic Coast Guard. So we find it quite contradictory that during the events of the Adriana, the cameras were not working, but now, all of a sudden, the Hellenic Coast Guard is very happily advertising their rescues from other distress situations. One thing is for sure: the crimes have not stopped since the shipwreck. We reported about this on a recent account from a pushback survivor off the island of Chios in the Aegean.

UR: Have the Greek and EU policies against migration contributed to the changing of migration routes in general?

AP: What we have been observing as Alarm Phone since the pushback regime intensified in Greece in the beginning of 2020 is that the routes in the Eastern Mediterranean have gradually shifted. People on the move choose to avoid Greece altogether due to the violence. We now see sailing boats or fishing boats departing from Turkey, Lebanon or Eastern Libya and, instead of going to Greece – which would make sense because it’s a much shorter distance – they are traveling all the way to Italy. So we have been observing much longer routes, which are also much more dangerous because of the longer distances.

UR: What do you mean by pushback regime?

AP: According to the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, “pushbacks entail a variety of state measures aimed at forcing refugees and migrants out of their territory while obstructing access to applicable legal and procedural frameworks. In doing so, states circumvent safeguards governing international protection (including minors), detention or custody, expulsion, and the use of force.” Such pushbacks have become so systematic on Greek territory and SAR (maritime Search And Rescue) zone that they now constitute a regime.

UR: All over Europe we see building fences, new closed camps and the general externalization of borders. Does the European Union still place value on human rescue?

AP: If we look also at other regions, not just the Aegean or the eastern Mediterranean Seas, and also if we look at how the EU has been trying to block and obstruct the activities of the civil fleet of boats of the civil organizations and civil rescue, it is safe to say that no, the EU does not place any value on rescue. Their priority is deterrence.

UR: Survivor testimonies say that they were pushed to identify nine Egyptian men as smugglers. And in general, after (and before) the shipwreck, the Greek state continues to speak about trafficking networks etc. Are these smuggling networks responsible for all these deaths that we see in the last decades in the Mediterranean?

AP: The Greek and European states are doing their best to place the blame on the ‘bad smugglers’ or on people on the move themselves. They do this because it draws attention away from the fact that there are no safe and legal ways for people to come to Europe. They cannot just board a plane and travel the same way that others among us do. Globally, the criteria based on which certain humans are allowed to move freely and others are not are based on racism, colonialism, and classism. There is no equality. So when there is this kind of discrimination between people, a kind of market space is created on the lack of rights. The real responsibility lies with fortress Europe and state policies that impede the free movement of people and of course encourage those who try to take advantage of certain situations to profit from them.

UR: We see all this smugglers narrative serving also for the criminalization of the people on the move themselves and of people in solidarity. Is Alarm Phone also at risk of criminalization?

AP: Yes. Anyone that advocates for freedom of movement, anyone fighting against discrimination and against racism and against borders is an enemy. So it is not surprising that they are targeting solidarians* as well.

*Solidarians is a term frequently used in movement spaces in Greece and throughout Europe to describe people volunteering to help migrants and refugees.

As of the publication of this article, 40 migrant survivors are suing the Greek Coast Guard for the Pylos shipwreck, saying they deliberately neglected to save passengers. Nine Egyptians charged as the smugglers are still incarcerated.

After the shipwreck, a movement spread across Greece calling for justice for the migrants. See our video below.

Cover image by Niko Georgiades for Unicorn Riot.

Related:

Greek Seas: Europe’s Largest Migrant Cemetery [July 2023]

Greece’s First Housing Squat for Refugees & Migrants, Notara 26 [May 2018]

Life Vest Mural Draws Attention to the Plight of the Refugee [Nov. 2021]

Go Game [Film] [Feb. 2022]

Crisis: Borderlands [March 2017]

For more from Greece, see our archives.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

![[Cover Photo] sourced via Creative Commons.](https://unicornriot.ninja/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Untitled-1-420x236.png)