KARE 11 Outed a Whistleblower to the Minneapolis Police. He Killed Himself.

How the Press and City Failed Alan Ditty

A Minneapolis city employee blew the whistle, and killed himself after he was identified and fired. Nearly six years later, there has been no official accountability nor substantive media coverage of this corrupt investigation.

Alan Ditty—union pipefitter, dedicated worker, son and brother*— died on March 12, 2016. He had worked for the city of Minneapolis for 32 years, and was only one year away from early retirement eligibility. He called in sick just three days over three decades.

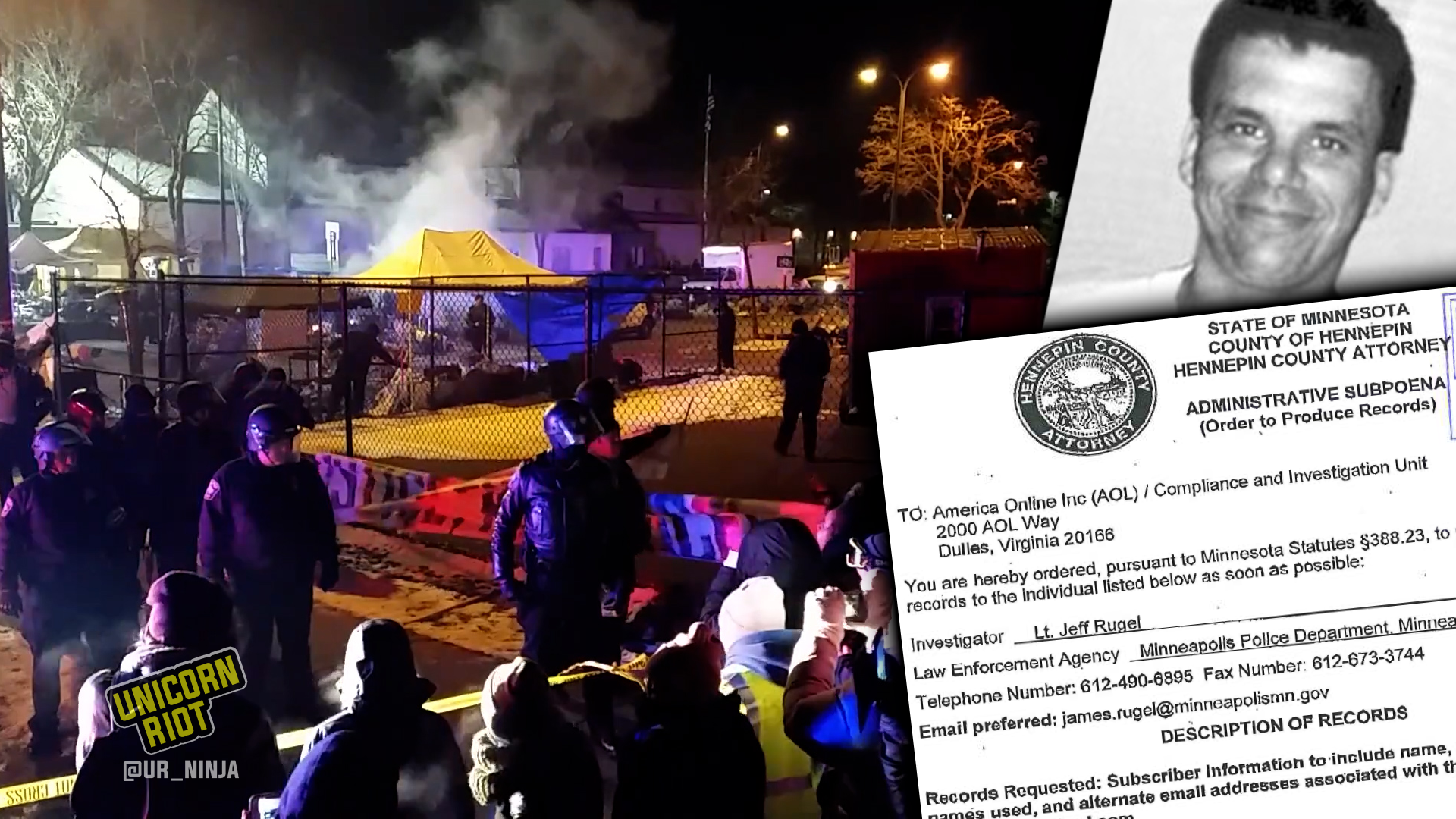

Ditty cared deeply and fiercely for his employees and the public he interacted with on a daily basis. When he discovered that a raid was imminent on a Black Lives Matter encampment after the fatal police shooting of Jamar Clark, he feared for everyone’s safety. The city planned to have police remove the protesters, and then sanitation workers would immediately clean up the remnants of the encampment.

Ditty was aware that in addition to tensions between protesters and police, men with handguns intended to come to the encampment (the men would later be identified as white supremacists; Allen Scarsella shot five unarmed protesters in November). Ditty and his workers were not trained to work in hostile situations, let alone those with a viable threat of armed conflict.

Listen to a nearly hour long audio episode summarizing the Ditty investigation below. For more context and background and to hear perspectives from Alan’s family, listen to the podcast at the bottom of this article.

First, he went to his immediate supervisor Dave Herberholz with his concerns and those of his workers. But according to his mother and sister, he received no response. Ditty’s sister Sheila said that in his personal handwritten notes, he wrote that a sergeant with the Minneapolis Police Department used the “f-bomb” at him, saying that he did not have a choice, and that sanitation workers would participate in the cleanup.

Out of options, Ditty opted to write to Kare 11, Minneapolis’ local NBC affiliate. Because Ditty feared retaliation for blowing the whistle, he created a new AOL email address that did not include his real name or indicate his identity.

On the evening of Friday, November 20, he used this email address to send a copy of the police department’s plan to raid the camp, which was set to take place the next Monday. His hope was that with news cameras around, all sides would behave more civilly and there would be a level of accountability.

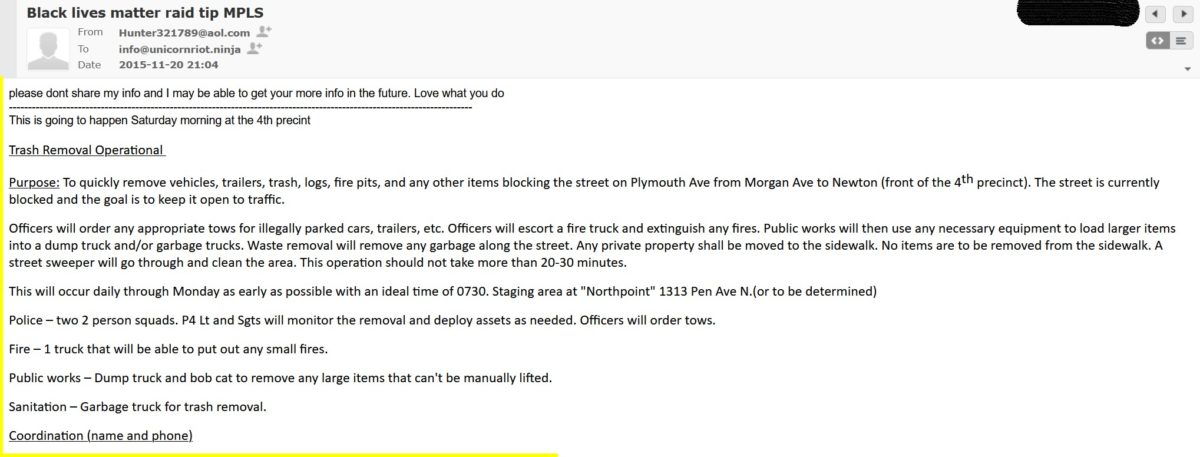

Although the content of his email was redacted in the copies received through a public records request, Ditty sent an email to Unicorn Riot on November 20 as well, titling it “Black lives matter raid tip MPLS.” Ditty wrote that the raid would happen on Saturday and included what looks like copy/paste from the city’s “trash removal” operation.

After Ditty sent the anonymous email to KARE11 and Unicorn Riot blowing the whistle on the raid he didn’t have to wait long before receiving an email explaining that the city canceled the raid for “several reasons.” He wrote Unicorn Riot back on November 21 at 3 a.m. saying “City leaders higher up put a stop to this event.“

(The raid eventually happened in the early morning of December 3, 2015, in a similar fashion that Ditty sent in the email.)

The same night he sent the message to KARE 11, managing editor Rita Hathaway forwarded it to Scott Seroka, a spokesman for the Minneapolis Police Department. Seroka had recently departed from KARE 11 for a new job with the City as a police spokesperson.

“Hmmm. Is this legit?” Hathaway wrote to Seroka on November 20. Since it included the entire original tip, Hathaway’s message included Ditty’s AOL email address.

What followed was a collusion by Minneapolis’ police and public works departments to punish Ditty for acting to protect the safety of his workers.

It is a fundamental journalistic principle that the reporters should never reveal their sources, who could face retaliation for communicating with the press. KARE 11 may have thought that because Ditty’s original email did not include a name, he could not be identified. Unfortunately, every online communication leaves a trail of digital breadcrumbs unless one takes intentional steps to cover them.

Alan’s tip was not the only email communication that was forwarded by KARE 11 directly to Minneapolis Police without identifying information being scrubbed.

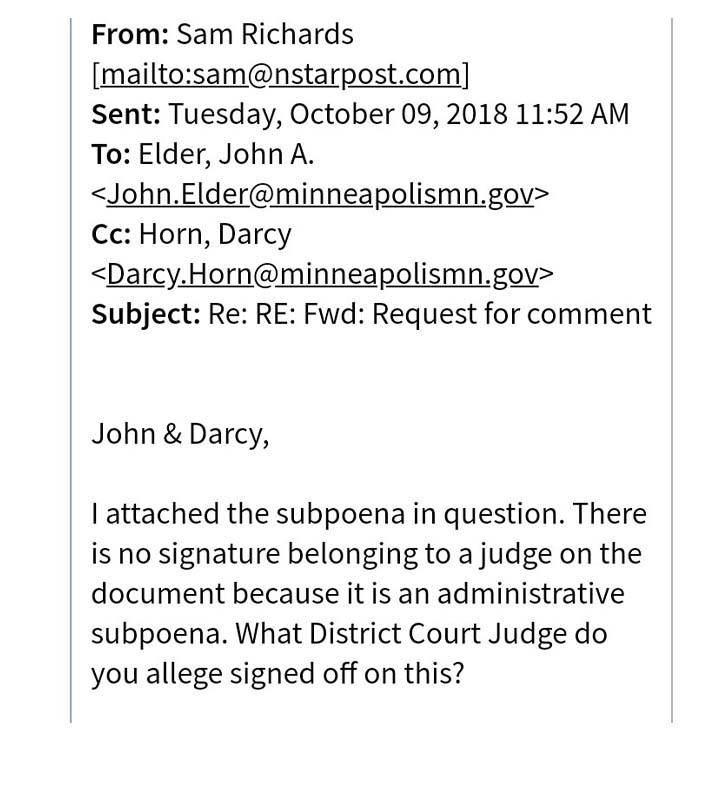

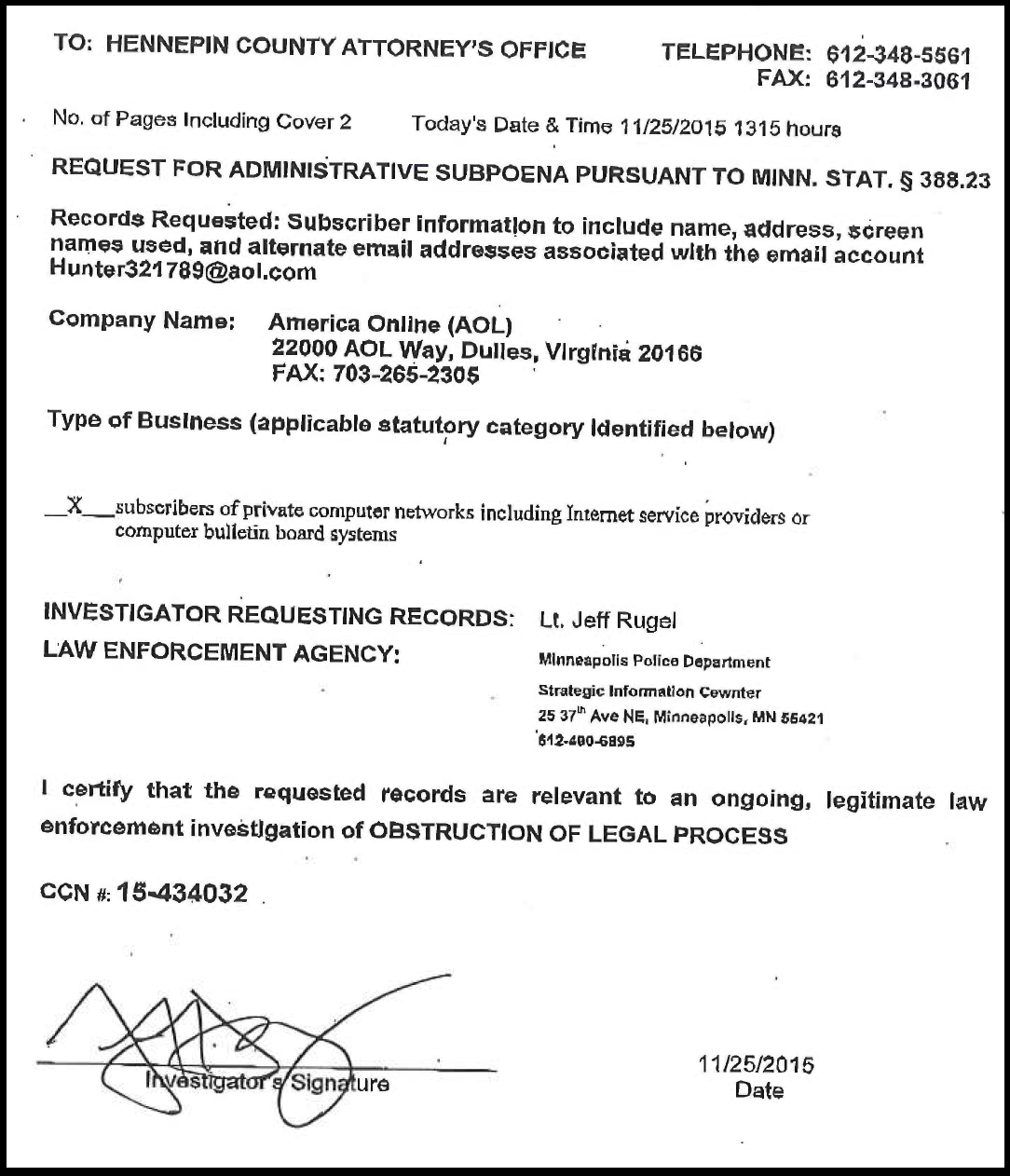

Lt. Jeff Rugel of the Minneapolis Police Department’s Strategic Information Center (SIC) sent an administrative subpoena on November 25 to AOL. Administrative subpoenas are not approved or seen by judges before being issued – a detail that MPD spokespeople continued to lean on as justification for this surveillance. “Records Requested: Subscriber information to include name, address, screen names used, and alternate email addresses associated with the email account [email protected],” it read.

(In 2019, Unicorn Riot exposed that MPD Lt. Jeff Rugel, was using fake social media accounts to monitor 2015 protests after Jamar Clark was killed by police. On March 31, 2021, Rugel testified during Derek Chauvin’s trial about his role leading MPD’s Business Technology Unit, working with the city’s surveillance camera network and how he helped create the SIC which functions as a fusion center where police monitor news broadcasts, surveil social media, and coordinate their response to events like natural disasters or social unrest and protests.)

At the end of January, he was called into the office and placed on paid suspension. Ditty’s sister said that at the time, he had no idea why he had been suspended. For five or six weeks, she said he was forced to sit, speculate and ruminate in his own thoughts which had become increasingly dark.

“The only thing he could think of was the tip he sent to KARE 11, and that they were angry,” Sheila Ditty said. “But he didn’t know.”

He was told he could talk to no one—including friends and family—about being on paid suspension. His coworkers were told he was out sick. When asked for documentation from this supposed internal investigation, the City was unable to produce a single document.

When he was finally asked outright about leaking the plan to KARE 11, Ditty admitted he had done it and told them he had done so to protect his employees. Several days later on March 4, he was fired.

Throughout this process, Ditty was distraught. Sheila Ditty said that he wrote at the time in his personal notes that he felt like a squirrel trapped in a cage. “He was bullied and tortured,” Sheila said. Additionally, none of his friends from work were in communication with him – adding to his foreboding sense of isolation.

One week after he was terminated from the job he loved, Ditty took his own life in his Brooklyn Center home. He left no suicide note.

Sheila said her brother had had no idea what the consequences would be for speaking up. She said he thought it was “all confidential and all private, that his name would never be given out.”

KARE 11 promised the incident would be investigated. In response to an email request for comment, John Remes, president and general manager of KARE 11, said that “when we were made aware of Mr. Ditty’s passing… we reviewed our records and were not able to identify an email outgoing to police due to the fact that the original correspondence occurred many months earlier.”

Remes said that because deleted emails are removed permanently from servers after 60 days and the email in question was redacted in documents produced through FOIA requests, “we are unable to see exactly what it included.” He did not respond to further emails including questions about KARE 11’s source protection policies or the status of the investigation.

Years after a KARE 11 reporter sent a whistleblower’s email to the police, it’s unclear if the outlet has taken any steps to ensure revealing sources is avoided in the future. The reporter in question has retained her position as managing editor.

Following these revelations this reporter in conjunction with 98.9 KRSM-FM produced a 4-part radio series about Ditty’s story including interviews with his sister, mother, union appointed lawyer, the ACLU of Minnesota and others intimately involved in the scandal. This remains the vast majority of coverage of this sordid affair. The circumstances around his death were reported in a City Pages article, but the story of the press and the city failing Ditty received no national media attention. (City Pages’ website has been removed from the Internet by the publishers of the Star Tribune, which then crushed an independent archiving effort.)

An aggressive political climate which has put journalism under greater scrutiny requires media outlets to demonstrate greater accountability. An inability for a local media market to cover stories of such vast import increases the odds that such malfeasance will reoccur and with greater frequency.

The main objective of journalism is to hold power to account – not maintain access to officials in order to churn out crime-related stories often told only from the police’s perspective. The story of Alan Ditty is known widely throughout the Twin Cities media establishments yet none have offered any coverage to the Ditty family nor pressed police for answers.

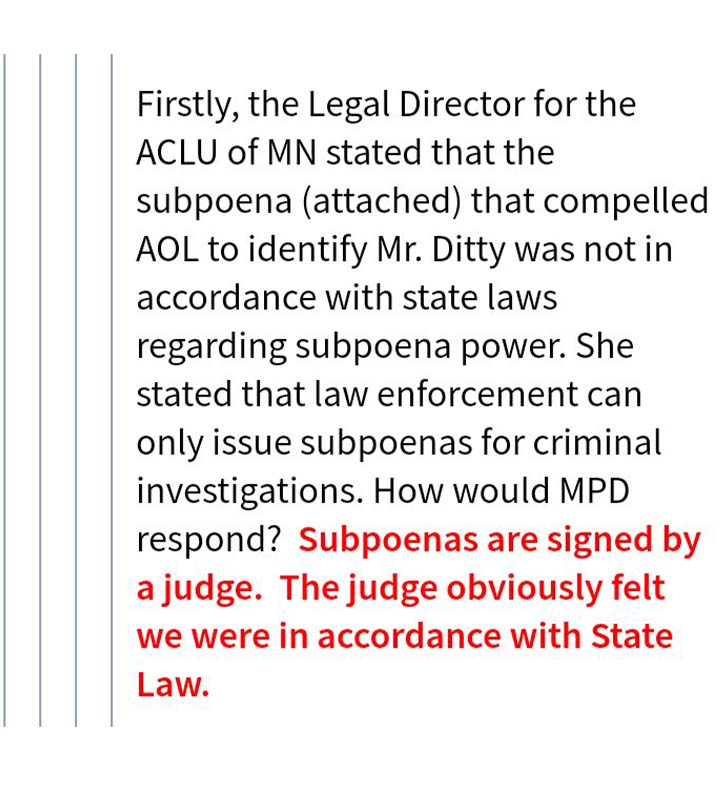

After months of outreach through emails and calls to Minneapolis Police Department spokespeople that were mostly fruitless, an in-person attempt was needed. Of particular interest was the legality of issuing a subpoena for someone who was not the target of a criminal investigation. Theresa Nelson of the ACLU of Minnesota asserted that using subpoena power in this way is not within statutory authority under state law. When asked in emails to comment on this alleged improper use of subpoena power, PIO John Elder stated that a district court judge signed off on the subpoena — which a County Attorney spokesperson refuted.

After waiting outside the public information office at City Hall for about thirty minutes, PIO John Elder opened the door, handed journalist Sam Richards a sealed letter, then slammed the door as Richards attempted to ask why Elder claimed the subpoena had been approved by a district court judge.

An email to the MPD Public Information Office attempting to seek clarification after they claimed a judge approved the subpoena targeting Ditty’s AOL account.

Numerous emails attempting to question the Minneapolis Police about subpoena power and judicial oversight were dodged.

Soon thereafter, Richards ran into PIO Elder in the hallway as he and another PIO were exiting. This awarded Richards the opportunity to ask questions without any obfuscation. Elder insisted that he “made a mistake” when he repeatedly claimed that a district court judge signed off on the subpoena.

When asked if the MPD uses subpoena power against those not under criminal investigation with any frequency, Elder directed him to ask the County Attorney. When asked if anyone from the MPD had spoken with the Ditty family, Elder was similarly dismissive.

Elder and the MPD also refused to release the unredacted plans for the raid that Alan forwarded to KARE 11; the name of the officer that was in charge of the raid and allegedly swore at Alan; nor would comment on whether the MPD has changed policies or learned anything from this scandal.

John Elder has since departed the Minneapolis Police Department but the callous indifference displayed for the life of a man who worked tirelessly for Minneapolis for decades remains a hallmark of the Department. According to the Ditty family, no one from the MPD nor any other City official ever reached out to express their condolences. The family still seeks and hopes for justice.

The story is never solely the content of a leak. How officials respond to, prosecute, and even punish whistleblowers at all levels of government is critically important.

News outlets must take active steps to protect the confidentiality of their communications. When journalists fail to protect their sources, the consequences can be severe. Sources could lose their jobs, face retaliation, or even go to prison. Failure should be acknowledged as such, and internal source protection policies reviewed and modified.

When asked about her son and what closure might look like, Alan’s mother Dorlene sighed heavily. “I don’t know. He was just such a great person, he cared so much about those people at work. I don’t know. It just makes me so sad.”

Listen to the nearly hour long recap of this investigation to hear from Alan’s family, the ACLU, Alan’s lawyer and numerous others. Former Mayor Betsy Hodges declined to comment for this article.

If you or a loved one is in crisis, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255). For resources in Minneapolis see here.

p. 343 Alan’s Tip subject line redacted

P. 706 Alan’s Tip subject line not redacted

Listen to a conversation with Ditty’s sister and mother, below. They explain what happened to Alan and what was not yet known at the time of the interview.

Correction: Original publication noted Ditty as a “husband, and father of two” that has been corrected to “dedicated worker, son and brother.”

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: