Origins of the PKK and the ‘Rojava’ Revolution: PT. I

The Arab Spring movement of 2011 – 2012 initiated one of the largest and most impactful international waves of protest in recent world history. This movement began in the small North African country of Tunisia, which soon toppled its longtime dictator, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, in a mostly bloodless coup. Egypt followed the same path when it also overthrew its longtime dictator, Hosni Mubarak, that following year. Despite the name however, the impact of the ‘Arab Spring’ movement wasn’t strictly limited to Arabs.

When the Arab Spring came to Syria, it presented the ethnic-minority Kurdish people a unique and historic opportunity to create their very own “autonomous region”, now officially known as the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). The autonomous region’s struggles for feminism, cooperative economics, and radical ecology has produced hope in what many call ‘Rojava’.

Who are the Kurds? What is Rojava?

‘Rojava’ is a Kurdish word which translates to ‘Western Kurdistan’. The Kurds are a middle eastern ethnic group who predominantly inhabit mountainous regions within the borders of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Some envision a ‘Greater Kurdistan’ which includes portions of current day northern Syria, northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, and southeastern Turkey, although political figures like Nazim Dabbagh, who represents Iraqi Kurdistan in Iran, dub this concept “impossible and […] more like a dream” due to the divided geography. Kurds also form significant parts of the population in large Turkish cities like Istanbul and Ankara.

A sizable Kurdish population lives in the southern portion of the ethnically diverse Caucasus Mountains as well as portions of eastern Iran. There is also a significant Kurdish diaspora in Europe consisting of about 1.5 million Kurds. More than half of the Kurdish diaspora (around 800,000) lives in Germany. The total worldwide population of Kurds is estimated to be somewhere around 30 million. Although most Kurds identify as Sunni Muslims, Kurdish people practice a wide range of religions, including various forms of Islam and Christianity as well as Zoroastrianism, an older monotheistic religion centered in present-day Iran.

Kurds Marginalized in Modern Turkey

Throughout their modern history, the Kurds, like other ethnic minorities in the Arab-dominated Middle East, have been subjected to generations of racism, colonialism and genocide at the hands of various empires, regional powers and nation-states. The breakup of the Ottoman Empire, in particular, led to a wave of nationalism across the empire’s former territories, including Kurdistan.

At the end of World War I, victorious Allied powers, namely the United Kingdom, France and Greece, occupied the defeated Ottoman empire, resulting in the rise of Turkish nationalism and the subsequent Turkish War of Independence. The Turkish nationalists, led by now revered ‘founder of the nation’, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, would emerge victorious in this war and establish the modern Turkish Republic on October 29, 1923.

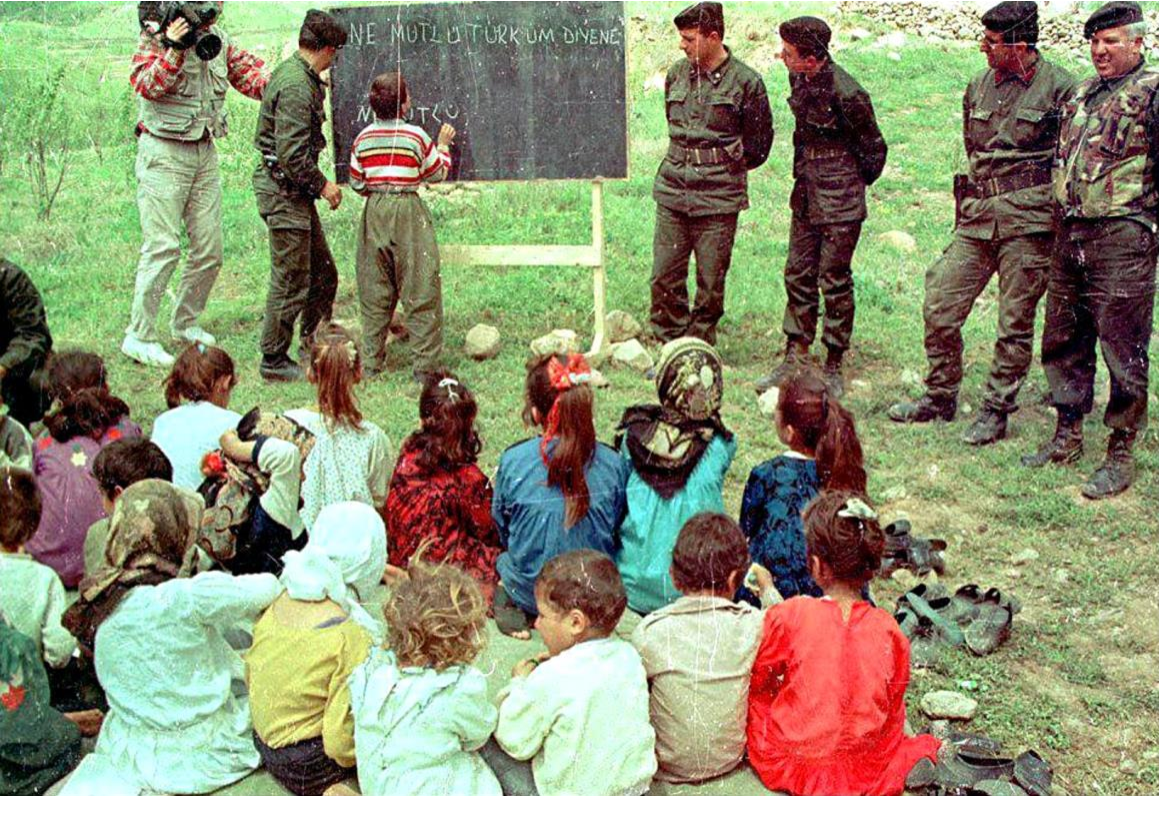

After securing Turkish independence, Atatürk initiated a series of significant reforms — he secularized the government and initiated a national campaign of ‘Turkification’. The explicit aim of this campaign was to unite all of Turkey’s diverse ethnic populations under one singular Turkish identity. This resulted in the state’s rejection and suppression of all non-Turkish ethnic identities. As such, the Kurds were no longer recognized as a distinct group but rather forcibly redefined as ‘Mountain Turks’.

These changes towards a exclusively Turkic identity represented a radical departure from the old Ottoman imperial system, which endured for centuries as a system of ‘suzerainty‘. The Ottomans divided administration into feudal regions, under an overall Islamic government (the sultan was also the caliph, claiming religious leadership of all Sunni Muslims), with local autonomy to traditional tribal village chiefs.

These issues only fed a growing Kurdish nationalist movement as more Kurdish chieftains (agha) began to demand an independent Kurdish state. This led to a series of Kurdish rebellions between 1925 – 1937, all of which were defeated by the new Turkish state.

Though the early Kurdish revolutionaries failed, others would later take note and inspiration from their example. One organization in particular picked up where its predecessors left off. That organization being the Kurdistan Workers Party (Kurdish: Partîya Karkerên Kurdistanê), otherwise known as the PKK.

Origins of the PKK

The roots of the PKK go back to the 1970s at a time when Turkey was experiencing intense political upheaval. A series of military coups between 1960 – 1971 had left the government fractured and weak. This combined with a failing economy contributed to the rise of a strong leftist revolutionary movement which began to challenge the status quo. One of the most prominent revolutionary organizations, and a precursor to the PKK, was the The Revolutionary Youth Federation of Turkey (Turkish: Devrimci Gençlik, DEV-GENÇ).

DEV-GENÇ played a crucial role in the movement by organizing numerous demonstrations against the government as well as protesting against the U.S military’s presence in Turkey. After the 1971 military coup, DEV-GENÇ was banned throughout Turkey, and many of its alleged membership were imprisoned. Though DEV-GENÇ continued to operate underground, it would never fully recover from the government ban and subsequent repression.

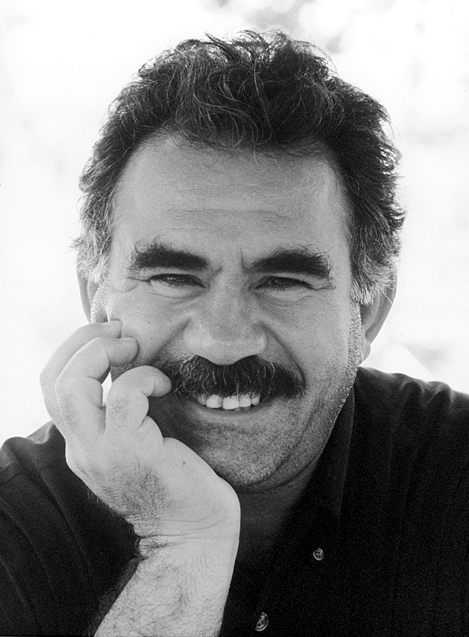

Angered by the continued brutalization and suppression of Turkish leftists and Kurdish students alike, in 1973 former DEV-GENÇ member Abdullah Öcalan formed an organization known as the “Kurdish Revolutionaries” in Ankara, Turkey’s capital city. It was in 1978 at a meeting in Diyarbakir, Turkey, that this group formally adopted its now most commonly known name, the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).

The PKK was formed with the explicit goal of organizing a communist revolution in Turkey, inspired by Marxist-Leninist ideology. As such, the organization initially had no initial desire to form an independent Kurdish state but rather a unified communist Turkey.

The rise of this leftist revolutionary movement provoked a violent right-wing reaction from both the state and its numerous affiliated right-wing militias. Thousands of people were killed during this wave of political violence as right-wing militants fought running street battles with left-wing groups. The PKK was heavily active in these battles as it armed its members for self-defense and carried out its own attacks against a variety of different right-wing and pro-government groups.

The political turmoil and division of that time had reached such heights that during the 1980 elections the Turkish government was unable to elect a president. As a result, the Turkish republic experienced a third military coup d’état led by Turkish military officer Ahmet Kenan Evren, triggering a huge wave of domestic political repression.

World-renowned Turkish journalist Mehmet Ali Birand reported that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was directly involved in the 1980 Turkish coup, a claim the CIA denies. The report centers around Minnesota native Paul Henze, who served as CIA station chief in Ankara at the time of the coup. Birand reported in his conversations with Henze that after the coup Henze reported back to Washington saying “our boys did it.” Henze was also involved in the CIA-funded anti-communist broadcasting outlet Radio Free Europe.

Due to Turkey’s strategic importance during the cold war (it joined NATO in 1952), the CIA was actively surveilling leftist political organizers in Turkey. The notorious and currently-incarcerated KGB double agent, Aldrich Ames, managed to infiltrate and identify members of DEV-GENÇ back in 1971 during his time with the CIA.

The 1980 coup would see the military seize absolute political control by suspending parliament, disbanding all political parties and banning free media. The Turkish government also escalated its repression against the Kurds by banning the Kurdish language. The PKK was a prime target of this repression, with many members executed or imprisoned. As a result, much of the organization was forced to retreat to the Turkish countryside and across the Turkey’s borders to neighboring countries where the PKK worked to reorganize in preparation for a sustained guerrilla warfare campaign against the Turkish state.

No Friends But The Mountains

After the 1980 coup, the subsequent political crackdown meant that very few leftist revolutionary organizations were still standing in Turkey. The PKK managed to survive this crackdown by moving its operations away from its traditional base in Turkey’s urban centers and into the rural Qandil Mountains where it continues to be based to this day.

This mountainous region runs across the Iraq-Iran-Turkish borders and has historically offered PKK fighters excellent protection from Turkish military interference.

Training and logistics bases were constructed in the neighboring countries of Syria, Iraq, Iran and nearby Lebanon. This move into other countries would see the PKK grow its international profile and activities as they established greater ties with other anti-imperialist movements around the world.

This strong sense of internationalism allowed the PKK to grow and thrive well beyond its original Turkish homeland. Its organizational flexibility is such that when the Turkish state applies pressure in one country, it can simply move operations to another. This strategy has been utilized by the PKK for decades and has played a large role in its massive international expansion.

Some of the PKK’s expansion can also be understood within the context of the global Kurdish diaspora. As a result of violence at home, many Kurds elected to leave Turkey during the 1970s – 1980s for western Europe. The PKK’s reach was assisted by this fact which led it to form an international chapter in Germany.

Out of all the countries that the PKK currently operates in, perhaps none of them are more strategically important than Iraq and Syria.

Enter Iraq and Syria

The Kurds of Southern Kurdistan (Kurdish: Başûrê Kurdistanê), otherwise known as northern Iraq, face a very similar, yet slightly different fight as their kin across the Turkish border. Much of that fight has been led not by the PKK but rather the Kurdish Democratic Party (Kurdish: Partiya Demokrat a Kurdistanê KDP), which rules much of Northern Iraq today.

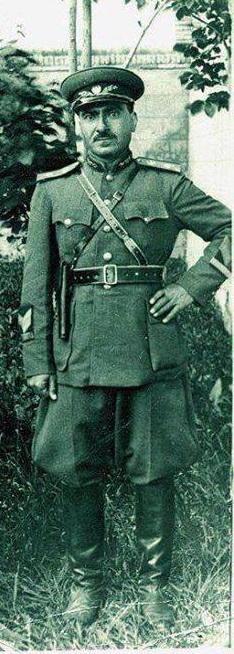

The KDP was founded by Mulla Mustafa Barzani in 1946. The Barzanis are a prominent Kurdish tribe from Southern Kurdistan (Northern Iraq) which continue to dominate Kurdish politics in Iraq to this day. Mustafa Barzani got his start as a military commander for a short-lived Soviet-supported Kurdish state called The Republic of Mahabad. It was here where Barzani was appointed Minister of Defence and led his Kurdish army to numerous victories against Iranian forces. The KDP’s fortune turned sour when the Soviet Union announced it was pulling out of the region in accordance with the Yalta agreement after the conclusion of World War II.

After the Soviet pullout, Kurdish forces continued to fight but were unable to stop the Iranians. Iran at that time was under the control of monarch and dictator Mohammad Reza Shah, who received significant financial and military assistance from the U.S. government.

The Republic of Mahabad was crushed by Iranian troops on December 15, 1946, after only two years of existence. Despite the seeming betrayal by the Soviets, Barzani fled to exile in the Soviet Union where he continued to lobby Soviet officials for support in creating a Kurdish state. That same year, the KDP was founded in Iraq and elected Barzani its president-in-exile.

When Barzani returned to Iraq in 1956, his relationship with the communists began to sour as the KDP sought more help from western countries, or any country that had disputes with the Iraqi government for that matter. Still, Barzani knew that the communists held significant political sway and continued to maintain tactical alliances with them. One of the KDP’s most tense and volatile relationships revolves around their history with the PKK.

That relationship dates back to the very beginning of the Turkish-Kurdish conflict in 1984. In that same year, Iraq was already five years into its own bloody US-backed war with Iran. the KDP found itself loosely allied with the Iranians against Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi forces in exchange for Iranian help in forming a Kurdish state in Iraq.

Due to the intense fighting of the Iran-Iraq war in the south, Iraqi-Turkish borderlands in Northern Iraq were left virtually abandoned. As a result the KDP was able to establish a strong military presence there and allowed the PKK to base its forces there as well. This new presence in Northern Iraq formally gave the PKK one of its two most important vectors of penetration into Turkey.

The other critical vector of attack was Syria. During the 1980s, Syria was experiencing its own political turmoil as the Syrian state battled political enemies from both inside and outside the country.

One of Syria’s greatest political enemies was, and still is, the Turkish government, with whom the Syrians have a significant territorial dispute over control of the commercially important Euphrates River. The shared interests of combating the Turks allowed the PKK to form a tactical alliance with the Syrian government which led to the establishment of PKK training bases in Syrian government-controlled territory.

In 1982, the Second Party Congress of the PKK was held in Daraa, Syria. It was here where the PKK developed its initial plans for its guerrilla operations in Turkey. Two years later, on August 15, 1984, the PKK launched their first attacks against Turkish military forces in the towns of Eruh and Şemdinli. This attack would effectively mark the beginning of the PKK’s ongoing guerrilla war against Turkey.

The Beginnings of the ‘Turkish-Kurdish Conflict’

By 1984, the PKK had gone from being a little-known secretive organization of only a handful of intellectual students to a formidable and well-funded guerrilla army of thousands with a vast local and international support network. Using its bases in Iraq and Syria, the PKK continued to launch cross border hit-and-run attacks against Turkish forces.

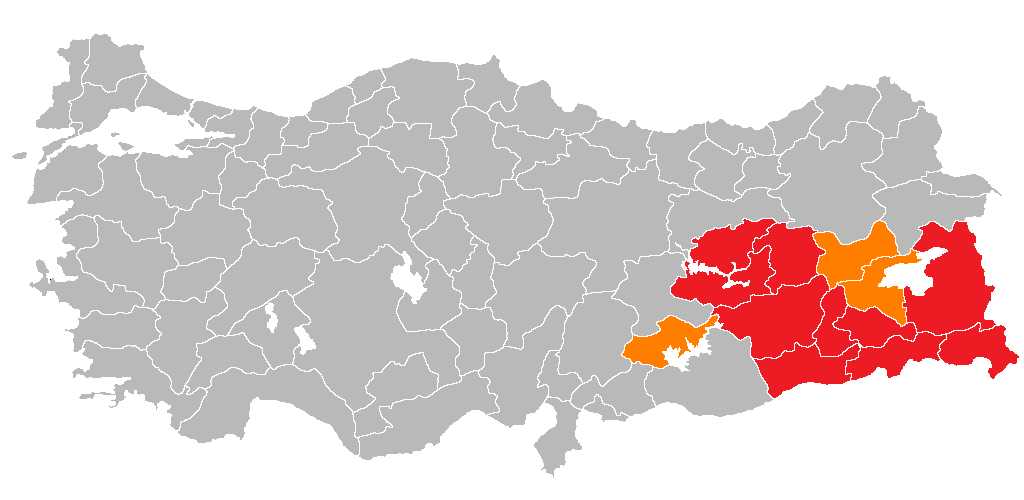

The war continued to rage out of control in the Southeastern Turkish countryside and reached its peak in the early 1990s. In response to the PKK rebellion, the Turkish government declared a state of emergency in the predominantly Kurdish regions of Turkey labelled above.

This state of emergency was initially declared in 1987 and was extended 42 times until 2001. This meant that citizens living in these areas could be subjected to forced relocation at virtually any time, without warning. Curfews and roadblock checkpoints were enforced by the Turkish military as local governors were given broad and sweeping powers to restrict freedom of movement and basic human rights. Freedom of the press was also non-existent as journalists were not allowed to access these areas.

In an effort to stamp out PKK guerillas the Turkish state employed a strategy of state terrorism against any and are believed to be affiliated or collaborating with the PKK. Turkish military massacres/executions against civilians is believed to have resulted in the deaths of thousands of people during this period.

Systematic torture and disappearances of Kurdish civilians by the Turkish security services was also detailed in a 1993 Human Rights Watch report.

Though it pales in comparison to Turkish atrocities, the PKK’s human rights record during this period is also marred by intense violence. The PKK often attacked civilian workers such as teachers and doctors and any Kurdish elites that it deemed as government collaborators/infiltrators. These attacks were justified by the PKK within the context of needing to stop Turkish imperialism by any means necessary. As a result, it is estimated that thousands of civilians were killed in PKK military operations/executions between 1988 – 1999.

The organization is also accused by pro-Turkish/American government sources of being involved in the international drug trade as well as utilizing child soldiers in its army. These claims in particular have consistently been denied by the PKK and the majority of them have yet to be substantiated by independent sources.

Strong international condemnation of the PKK’s reported human rights violations led to a decrease in these activities, though allegations of human rights abuses by the PKK persist to this day. In particular, a recent 2020 United Nations (UN) report alleges several abuses against children perpetuated by PKK-affiliated forces in the ongoing Syrian Civil War.

Frenemies Become Enemies Again

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent Gulf War of 1991 led to significant changes in global geopolitics. As a result, for the first time ever in 1992, the Turkish military launched a joint military operation with the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) against the PKK in Iraq. It’s suspected that the KDP’s sudden change of alliance came as a result of wanting to forge better relations with the western world via Turkey.

The Turkish-led military operation included tens of thousands of Turkish/KDP troops backed up with tanks and airplanes. Despite possessing a clear numerical and technological advantage, the operation failed to remove the PKK from its bases in northern Iraq.

A year later, for the first time in 1993, Abdullah Öcalan announced a unilateral PKK ceasefire. Then Turkish president Turgut Özal agreed to the peace process but died soon after under suspicious circumstances on April 17, 1993. Özal had previously dodged at least one documented assassination attempt on his life five years earlier in 1988. His son and former politician Ahmet Özal further claims that his father was the target of another assassination attempt two months prior to that attempt.

After Özal’s death, then-current Turkish Prime Minister, Süleyman Demirel, was elected to replace Özal. As President, Demirel and the Turkish government rejected the ceasefire, resuming and escalating its war against the PKK using “scorched earth” tactics. This amounted to the systematic de-population and de-forestation of Kurdish rural villages in southeastern Turkey. It’s estimated that during this time thousands of Kurdish villages were destroyed and tens of thousands of Kurdish people were executed by Turkish forces. Millions of Kurds were also internally and externally displaced as a result of the Turkish campaign.

After the failure of the first ceasefire, the Turkish-Kurdish conflict continued to escalate in Turkey and Iraq. With Saddam’s blessing, Turkey would continue to launch search-and-destroy operations in Iraq in pursuit of PKK forces. The PKK’s leadership and associates became high-value targets for assassination, kidnapping and extortion by pro-Turkish government militias.

Further economic and legal pressure was put on the PKK’s international activities after the U.S. added it to the list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO) in 1997.

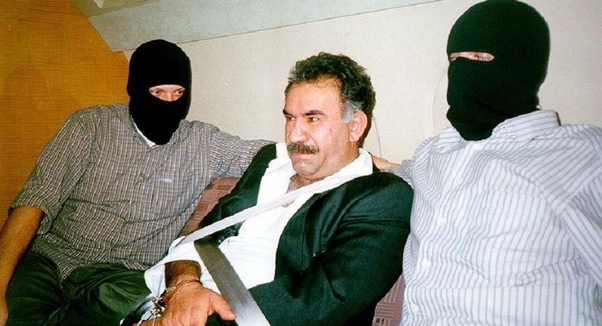

Öcalan’s Capture

Above all, Öcalan remained at the top of Turkey’s most wanted list and had managed to evade efforts to capture or kill him for well over a decade. Since the beginning of the conflict, Öcalan had been based in the Syrian capital of Damascus. This all changed in 1998 when the Syrian government caved into Turkish and American pressure and expelled him from the country.

Öcalan would once again be forced on the run, fleeing to several countries in search of another sanctuary. The American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in conjunction with the Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MİT) spied on Öcalan everywhere he went, working to ensure that he would not find a safe haven.

Öcalan eventually ended up at the Greek embassy in Nairobi, Kenya. At that time there were over 100 U.S. intelligence operatives in Kenya investigating the unrelated 1998 bombing of the American embassy. As a result, Öcalan’s presence in Kenya was immediately reported back to the Turkish government, which dispatched a group of commandos to Nairobi to capture him. With the help of an unnamed Kenyan intelligence operative, the commandos succeeded and Öcalan was sent back to Turkey to stand trial for his alleged crimes against the state.

Öcalan was immediately put into isolated detention on the small, island prison of İmralı, where he has remained for the past 22 years. During his trial, his legal team says they were targeted, harassed and repeatedly denied access to their client. On June 29, 1999, Öcalan was charged with the crimes of “treason and separatism” and sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment after Turkey abolished the death penalty in 2002.

Political Transformation

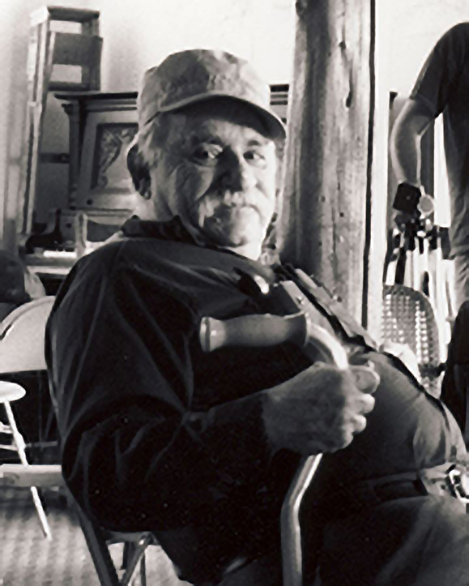

While in prison, Öcalan began to reflect and re-examine many of his traditional communist beliefs. He began to read a wide variety of various philosophers published works. He took particular interest in the writings of anarchist philosopher Murray Bookchin. It was from Bookchin’s political concept of ‘Communalism’ that Öcalan developed his own concept called ‘Democratic Confederalism.’

Both concepts combine various forms of Socialism (Anarchism, Communism, etc) and explicitly reject the top-down, vanguardist government model in favor of decentralized communes/councils to organize society. Democratic Confederalists further emphasize the importance of feminism (Jineology) and ‘radical ecology’ as guiding principals of the movement.

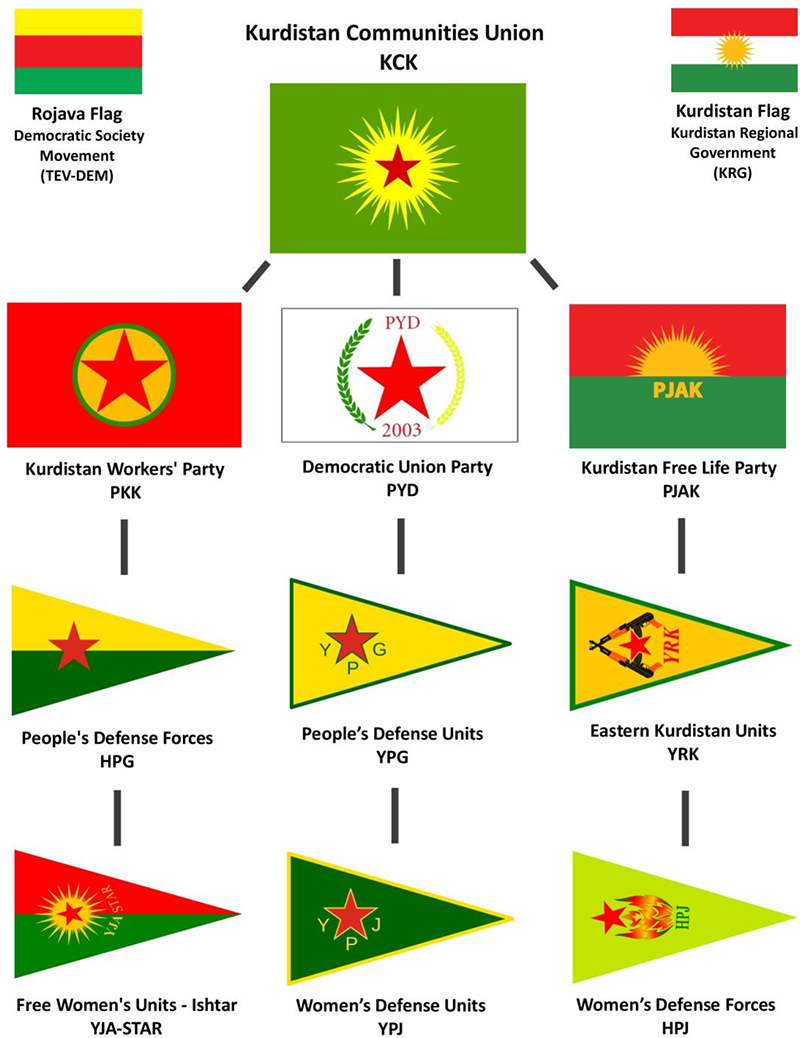

Öcalan’s political transformation led the PKK to make drastic changes to its structure. After his sentence was commuted in 2002, perhaps in an attempt to get around legal restrictions imposed by the U.S./Turkey, the PKK underwent a series of name changes from the PKK to the Kurdistan Democratic and Freedom Congress (KADEK) to the People’s Congress of Kurdistan or “Kongra-Gel” (KGK). The organization finally reverted back to its original PKK namesake in 2004.

The same year that Öcalan’s sentence was commuted, the PKK’s affiliated organization in Iraq, the Kurdistan Democratic Solution Party (Kurdish: Partî Çareserî Dîmukratî Kurdistan PÇDK) was founded. This was followed by the establishment of the Syrian Democratic Union Party (Kurdish: Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat, or PYD) in 2003 and the appearance of the Iranian based Kurdistan Free Life Party, or PJAK (Kurdish: Partiya Jiyana Azad a Kurdistanê) in 2004.

In 2005, the PKK established the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) which functions as the umbrella political organization for the PKK’s affiliates in Turkey, (KGK) Iraq, (PÇDK) Iran, (PJAK) and Syria (PYD). In this way, the KCK works to implement the political directives and objectives expressed in Öcalan’s democratic confederalism across all PKK affiliated organizations.

These PKK-affiliated organizations have achieved varying levels of success in their respective countries. The most successful of them all, however, has been the Syrian PYD, which is credited as being the political driver for the ongoing ‘Rojava revolution‘ in Kurdish areas within the borders of northern Syria.

Seeds of Rebellion Spark a Revolution

After expelling Öcalan in 1998, the Syrian government banned all Kurdish political parties, including the PKK. In Syria, the PKK once again found their political activities forced underground. This would lead to the creation of a separate yet almost identical political party in the PYD.

The PYD first showed its impressive organizing ability during the 2004 Qamishli riots, which grew out of Arab-Kurdish conflict following a football match. It was during this particular uprising that the Syrian government first took note of the PYD’s ability to organize and turn out large numbers of people to their demonstrations. After these riots, the Syrian government amped up its repression by jailing many Kurdish activists. Some of those arrested say they were physically and psychologically tortured, with the worst punishment being reserved for alleged PYD members.

Despite this, the PYD continued its existence as an underground organization right up to the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011. By that point it had become one of the largest (if not the largest) Kurdish-led political parties in Syria.

When the Arab Spring came to Syria in 2011, the Syrian state responded with a systematic campaign of mass brutality and repression that shocked the world and angered millions. A mass armed resistance movement grew rapidly and governments hostile to Bashar al-Assad (USA, Saudi Arabia, etc.) began funding various anti-government militias in Syria. In turn, the Russian, Chinese and Iranian governments would ally themselves with the Assad regime, turning the Syrian civil war into one of the deadliest and most complex proxy wars in modern world history.

At the outbreak of civil war in Syria, the PYD initially aligned itself with the Syrian revolutionaries in the Free Syrian Army (FSA) but was also critical and suspicious of some of the more conservative, well-funded Islamist elements within the resistance, such as the Islamic State (IS) and Al-Nusra front.

To help protect their Kurdish communities, the PYD formed its military wing, the People’s Protection Unit’s (Kurdish: Yekîneyên Parastina Gel – YPG) at the beginning of the war in 2011. Initially, YPG was a mixed-sex militia but as recruits started to pour in, a separate yet parallel all-female militia was created in 2013: the Women’s Protection Units (Kurdish: Yekîneyên Parastina Jin – YPJ).

The Syrian government’s preoccupation with the civil war against the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and Islamist rebels gave the Syrian Kurds a free hand to establish their own autonomous territory. Accordingly, government forces mostly withdrew from the Kurdish-dominated areas of northern Syria, facilitating the creation of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). Although previously called ‘Rojava,’ it was decided to drop that name in favor of AANES so as to better reflect and respect the multi-ethnic/religious diversity of the region.

2014 saw the dramatic escalation of the NES’s fight against Islamist rebels, particularly the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) or “Daesh” during the siege of Kobanê. ISIL initiated this siege in an attempt to cripple the YPG/YPJ which had its headquarters stationed in Kobanê. Though outnumbered and outgunned, the YPG/YPJ and their allies held out in the city center for many months, fighting ISIL forces to a standstill.

This improbable outcome shocked many in the international community who expected Kobanê to fall within days. When asked why the U.S. wasn’t doing more to help the besieged Kurds, then U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry bluntly stated, “Kobanê does not define the strategy for the coalition in respect to Daesh (ISIL).”

Due to its strategic military relationship with Turkey, the U.S. made it clear that it had no intentions of helping the Syrian Kurds. Instead, U.S policy poured military aid into the Arab-dominated FSA militias, some of who had close links with reactionary Islamist groups like ISIL.

As the siege of Kobanê dragged on, political pressure began mounting on the U.S. to do more to help the besieged Kurds defeat ISIL. As a result, the Obama Administration was forced to reverse course and escalate its air bombing campaigns against ISIL targets in and around Kobanê. U.S. air support was pivotal in breaking the siege and led to an eventual YPG/YPJ victory over ISIL forces in the region.

After the YPG/YPJ’s successful defense of Kobanê, the U.S. reversed policy by ending its failed $500 million dollar program to train and equip the more Islamist-aligned FSA factions and instead poured its funding into the newly established Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). This move deeply angered Turkey, who saw support for the SDF as a U.S. realignment that could create conditions for a possible new de facto Kurdish state on its southern border.

The ensuing American-Kurdish alliance proved to be the death knell for ISIL and the borders controlled by the new Kurdish-led autonomous territory grew substantially. After the SDF largely defeated ISIL in 2017, the Turkish military and its proxies responded with a series of operations meant to nullify and contain the Rojava revolution.

The Kurds petitioned their American allies to do something to stop these Turkish invasions and while the Americans would criticize the Turks in public, on the ground, in 2019 it would actually pull its forces away from the Turkish-Syrian border, effectively giving Turkish forces a green light to continue their invasion and carry out atrocities against Kurdish populations.

Today Turkey and its proxies control the northwestern Afrin district of Syria and other areas farther east, while, as of late July 2021, Turkey continues to bombard areas in the Aleppo district such as Manbij in an effort to consolidate control. Turkish advances in military drone technology, seen in conflicts in Libya and a war in 2020 between Armenia and Azerbaijan, have been increasingly pivotal to its military strategy.

It should also be noted that turmoil continued in southeastern Turkey as well. In 2016 a massive campaign severely damaged Diyarbakir, leading to the displacement of tens of thousands of Kurdish residents. Such campaigns are seen by some observers as an effort to erase the legacy of centuries-old multicultural areas. The People’s Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi – HDP) has attempted to defend minority rights of Kurds and its leaders have faced imprisonment, as well as actions to remove many locally elected HDP mayors and replace them with appointed officials loyal to Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in tandem with 2019 military actions into Syria, and further legal actions like terrorism trials in 2020.

Conclusion

Since its inception the Rojava Revolution has experienced many ups and downs. In accordance with democratic confederalism, most, if not all, critical infrastructure like healthcare and education has been collectivized and placed under community ownership. Significant rights for women and historically disadvantaged ethnic minorities have been granted. Tremendous ecological progress has been made as a result of reforestation projects and continued development of ecological infrastructure, such as the installation of solar panels to provide power to rural villages.

Despite these historic achievements, handicaps and challenges continue to hamper the PKK-led Kurdish liberation movement. This success also did not come without a significant price as tens of thousands of people, mostly Kurdish civilians, died in the ensuing violence. Considerable economic and cultural damage has been sustained; it’s estimated that over the full course of the Turkish-Kurdish conflict, Turkey has spent a combined $336 billion to destroy the PKK, an effort which has so far been unsuccessful.

Due to intense pressure from Turkey, major compromises were made resulting in tactical alliances with once ideological enemies in Syria and the U.S. Though the Syrian Kurds in the PYD initially made tremendous gains through these alliances, much of those same territorial gains have now disappeared due to the inaction of their supposed allies.

Relations were further strained in 2018 when the U.S. Department of State issued a combined $12 million bounty for the capture of senior PKK leaders, Murat Karayilan (up to USD $5 million), Cemil Bayik (up to USD $4 million), and Duran Kalkan (up to USD $3 million) all while still financially and militarily supporting YPG/YPJ forces in Syria.

With ISIL largely defeated, the PYD have lost their strategic value in the eyes of the Syrian government and Americans who seem more aligned with guarding strategic Syrian oil fields than protecting people in the area.

It is currently unknown whether or not these tactical alliances will ultimately prove to be a help or a hindrance to the Kurdish struggle. What is certain is that the Kurdish spirit and will to survive will not be easily extinguished. History has shown after all, they have survived worse.

[EDIT 08.04.2021 : The Iraqi portion of ‘Greater Kurdistan’ is known as ‘Southern Kurdistan’ (Başûrê Kurdistanê) not ‘Eastern Kurdistan’ (Rojhilatê Kurdistanê)]

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

Unicorn Riot original reporting on Syria:

- International Volunteers of the Rojava Revolution - DOCUMENTARY FILM - (2019)

- Looking Beyond the Rubble: Aiding the Kurds After the Syria, Türkiye Earthquake (April 25, 2023)

- Revolution in Every Country Comic Series: Episode 1 – Syria: Erasing an Inconvenient Revolution (June 5, 2022)

- Origins of the PKK and the ‘Rojava’ Revolution: Part II (September 18, 2021)

- Origins of the PKK and the ‘Rojava’ Revolution: PT. I (August 3, 2021)

- Building Autonomy Through Ecology in Rojava (February 28, 2018)

- Kurdish Fighters Defend Afrin From Turkish Military Invasion in Northern Syria (January 25, 2018)

- Kobane Rebuilds as ISIL Control Diminishes in Syria (December 27, 2017)

- As Course of War Turns, Turkey Challenges Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (Rojava) (October 30, 2017)

- Solecast #20 Rojava Special w/ Janet Biehl (January 9, 2016)

- Pipeline Politics in the Syrian Civil War (September 20, 2015)

- Youth Press Conference Bombed in Turkey - Deprogram Ep. 12 (July 23, 2015)