New Federal Task Forces Under 287(g) Could Form ‘ICE Army’ From National Guard, State, Local & College Police

White House ‘Operation Homecoming’ Plan Calls for 20,000 Additional Personnel — DHS Looks to Mobilize National Guard

The Trump Administration has dramatically ramped up arrests and sweeps of people residing in the U.S., with new highly visible incidents and court cases unfolding every week and reaching new heights by mid-May. A new development could spell much larger scales of activity on American streets under 287(g) agreements between state and local law enforcement agencies and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). While 287(g) is mostly known for changing how arrestees are processed in county jails by sheriffs’ departments, there is a mode of agreement called the “task force model” which would make police available from local or state agencies to work as extensions of federal immigration police. This would make it vastly more likely for immigrants to get detained during routine law enforcement encounters, and massively expand how many local police could participate in federally-managed “sweep” operations.

One such sweep recently netted around 196 arrests of undocumented residents in Nashville. It was carried out by the Tennessee Highway Patrol and ICE using the 287(g) program. The operation “quickly emptied the pews of several Spanish-speaking parishes in the Diocese of Nashville,” according to the Catholic OSV News Service: “Tennessee Highway Patrol officers have been conducting traffic stops to identify and detain persons in predominantly Latino neighborhoods.” This is the pattern of activity that the 287(g) program is intended to intensify, because there aren’t enough federal agents to screen traffic at this scale.

In our experience covering high-level police structures and programs, personnel, manpower and coordination are usually quite constrained. Various state and local governments work around this by creating key documents like “memoranda of understanding” (MOU) and “memoranda of agreement” (MOA).

The controversial agreement between the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and ICE which surfaced on May 13 in American Oversight’s court case, is a great example of how these MOUs work. (A section on ICE and the IRS is below.)

New policies developed by President Trump’s top advisers – Stephen Miller and Tom Homan – aim to expand these forces. Miller called for deploying military and National Guard assets (archive) during the 2024 campaign, and recently demanded ICE make 3,000 detentions a day. In recent days, more reports have surfaced (archive) that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is looking to mobilize law enforcement agencies in 25 cities to enforce more civil immigration violation detentions, and the National Guard may become involved. DHS is trying to get 20,000 National Guard personnel. (A section on National Guard mobilization is below.)

The FBI is also possibly allocating one-third of its agents’ time in some field offices to civil immigration enforcement. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), U.S Marshals Service (USMS) and Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco Firearms and Explosives (ATF) are similarly getting tasked this way. (We have heard additional reports about other federal agents getting pulled from normal work and put onto this kind of activity but the full picture remains murky.)

Similar to the post-9/11 era, when the FBI fixated on ‘counterterrorism,’ a lot of other types of investigations these agencies are charged with, like weapons trafficking, white collar crime and human trafficking rings, will have to wait until the Trump Administration has sated itself or until other branches of the federal government intervene.

Sections: 287(g) Training and Memorandum Systems • How Task Forces and Multi-Agency Groups Get Constructed by Officials • ImmigrationOS: Where is the Data Stored for An “ICE Army”? • The IRS-ICE Agreement that Shook Tax Agency Leadership • “Project Homecoming” and Expanding Domestic National Guard Activity, via 287(g) • Tension in Newark; Additional Detention Centers Sought for ICE Operations • Report: Project 2025 Working Group Proposed Huge Police Command Network Under White House Control

287(g) Training and Memorandum Systems

287(g) takes the form of an agreement memorandum between local police and ICE. The program stalled after the Department of Justice made allegations back in 2011 that former Maricopa County, Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio had instituted racial profiling policies, but the program was never stricken from U.S. law.

Arpaio’s overall model, which included spectacular mass confinement for the media and detainee exposure to desert conditions, was a forerunner of the Trump mass detention style. The American Immigration Council warned at the time, “the practice of allowing local law enforcement to enforce federal immigration law increases the likelihood of racial profiling and pretextual arrests which leads to disastrous results for entire communities.”

Local police have turned up alongside federal immigration agents in places like Worcester, Massachusetts to help the feds carry out civil immigration detainers.

Around 40 hours of DHS video training for local police are supposed to forestall racial profiling and other racist outcomes.

As of May 28, there are 628 MOAs in 40 states. 99 agencies in 25 states have “jail enforcement model” agreements, 223 agencies in 30 states have “warrant service officer” agreements, and 306 agencies in 30 states have “task force model” agreements (Excel file). An additional 72 applications are pending: 8 jail enforcement models, 23 warrant service officers, and 41 pending task force model agreements (Excel file).

The interface to 287(g) could also include local regulations and policies about policing, immigration sweeps, joint operations, checklists for arrest encounters, and similar processes that should be available to the public and local policymakers. It has proven difficult for county boards and civil society groups to obtain policies about immigration sweeps.

The Miami Herald outlined 287(g) task force structures in detail: it “allows officers to challenge people on the street about their immigration status — and possibly arrest them… State and local officers are trained and deputized by ICE so they can question, detain and arrest individuals they suspect of violating civil immigration laws while officers are out policing the communities they are sworn to protect.”

In Florida, many police and state agencies have joined up in “task force” mode, which means they can try to enforce administrative warrants from executive branch immigration officials. There was a flashy sweep a few weeks ago to promote this. Even college campus police have been getting in on these task forces, bringing federal immigration enforcement down to the student dormitory level.

With little direct oversight from any bloc of public voters, college police departments will likely to be a tempting target for expanding immigration crackdown powers nationwide through systems like the 287(g) task force model.

According to ICE records, Florida higher ed policing for federal civil immigration now includes task force model agreements at Florida A&M University Board of Trustees, Florida Southwestern State College Police Department, Northwest Florida State College Police Department, and New College of Florida (a high profile takeover target of conservative education policy crusaders).

The Texas Observer reported on this “ICE Army” concept with Kristin Etter at the Texas Immigration Law Council warning it’s a “force multiplier of federal immigration agencies” with “officers in the streets stopping, detaining, questioning, interrogating, arresting” people. Law enforcement agencies have been joining 287(g) task forces as well, including the Texas National Guard and Attorney General’s Office. (Texas also has a separate MOU between the Texas National Guard and U.S. Customs and Border Protection under 8 USC section 1103(a)(10), 1357, 28 CFR section 65.80-85 and DHS Delegation 7010.3.2, as well as the Texas governor executive order GA-54; it says they use “State Active Duty” status and authority under Title 8 to “exercise the functions and duties of an immigration officer” under “supervision and direction of CBP [Customs and Border Protection] officials.”)

Immigration rights advocates in Maryland pushed to get a moratorium on 287(g) enrollments by state and local police, for at least the third year since 2020. However, as the legislative session wound down they came up empty-handed. Maryland resident Kilmar Abrego Garcia has become an international symbol this year after getting dumped into El Salvador’s notorious CECOT prison. The U.S. Supreme Court ordered the Trump administration to “facilitate” returning Abrego Garcia to this country but it has not done so.

Maryland sheriffs’ departments are joining 287(g) en masse, particularly along the northern side of the state. According to a Bolts report, the Democratic Party-controlled Maryland Legislature may not have realized the aggressive nature of 287(g) until it was too late in the policy cycle, despite the pleas of immigration rights advocates.

State Senator Karen Lewis Young told Bolts, “I think if [Abrego Garcia’s detention] had happened earlier in session, the 287(g) bill might have moved, because I think it gave everybody a much more realistic awareness of how dangerous that program can be.” However, Abrego Garcia was not detained under 287(g).

The ACLU of Maryland outlined how Intergovernmental Services Agreements (IGSA) are another avenue for the feds to get money to local police, as ICE rents jail beds to function as immigration detention centers. This allows Frederick, Howard and Worcester counties to generate revenue. The State Criminal Alien Assistance Program (SCAAP) is another similar revenue system.

The Maryland public defender’s office released a report (pdf) saying 287(g) agreements “undermine due process and make innocence irrelevant by requiring local law enforcement officials to screen, interrogate and detain without judicial authorization any arrestee suspected of being removable under civil immigration law. There is no exception for someone arrested based on mistaken identity.”

In Pennsylvania, the suburban political bellwether of Bucks County, outside Philadelphia, is the latest 287(g) flashpoint. Sheriff Fred Harran has been trying to enter into 287(g) without approval of the county commissioners, which the ACLU of Pennsylvania claims is illegal. In April, Harran confirmed he applied to get a “task force” model 287(g) program for about a dozen of his deputy sheriffs to act as ICE officers — not the more limited program that only applies to detention screening at the jail. On May 21 the Board of Commissioners voted 2-1 to oppose this enrollment.

Harran called the ACLU “lunatics” and his local critics “liars” in a “crabby rant” on a right-wing podcast. On May 13, ICE approved Harran’s 287(g) “Task force model” application.

According to the Bucks County Beacon, which uncovered the policy, Harran has not provided any written policy even though he claims his practices “would not include sweeps or raids, stating he has a ‘policy’ in place to prevent round ups.” On May 7, a number of civil society groups held a press conference in Doylestown before a county commissioners meeting (YouTube).

California, Illinois, and New Jersey ban 287(g) agreements statewide. In Minnesota, Cass, Crow Wing and Itasca counties have “task force model” agreements. Crow Wing, Freeborn, and Jackson counties have “warrant service officer” agreements. Jackson is the only Minnesota county with a “jail enforcement model” agreement.

How Task Forces and Multi-Agency Groups Get Constructed by Officials

We can compare 287(g) to other task force systems around the government, which are not often discussed.

Back on January 20, 2025, a White House “Presidential Action” statement, “Protecting the American People Against Invasion” declared that “Homeland Security Task Forces” (HSTF) should be created in all 50 states, although groups with that kind of name already existed in some areas. (Org charts for these kind of task forces are attached to the Florida plan linked below.) A DHS “finding of a mass influx of aliens” was signed on January 23, 2025 (pdf) to further justify these measures.

Unicorn Riot found that the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) is commonly used to assemble and pay for counter-protest riot squads across state lines, including for the 2024 Republican National Convention in Milwaukee and large crackdowns via Morton County at Standing Rock in 2016-2017 (using state troopers from Nebraska and Wisconsin, and police officers from various other states). The National Sheriffs Association was also an important actor in supporting EMAC activities, an adjunct effort to their “information war” against #NoDAPL protesters in the water protector movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

The period around the police killing of Daunte Wright and Derek Chauvin’s trial in Minnesota also saw a massive EMAC pull from Ohio and Nebraska. This also includes temporarily deputizing law enforcement officers, insurance provisions, and arrangements for paid services, off a menu-like arrangement, including munitions, travel, and wages. (Typically, a local sheriff or police chief, and someone in the state Department of Public Safety would sign off on EMAC requests from other states.)

Earlier, we also found that the High-Intensity Drug Task Force (HIDTA) in Minnesota is doing biometrics for the Minneapolis police without a listed nexus to drug cases at all. HIDTA units can also include staff from state National Guard offices and advanced technologies to cross-index people and run investigations. HIDTA are usually not considered to be “fusion centers” although their capabilities are similar, if not more robust. The Washington/Baltimore HIDTA was established in 1994 by the Office of National Drug Control Policy and covers 26 counties and 11 cities, including DC and parts of Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia.

Besides HIDTA there are also Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTF) in most metro areas. JTTF often has deputized local law enforcement with federal authorities attached, making oversight over such specially empowered local police a puzzling matter.

Some areas have Urban Areas Security Initiative (UASI) groups, which are mainly a channel for requesting grants, including a DHS/FEMA standardized equipment list — some proportion of these are supposed to be for disasters but a lot of the money can go to policing, surveillance, riot control and similar items. New Jersey has a chartered entity, Jersey City/Newark UASI, with an Urban Area Working Group. (pdf) More on that entity here. For much more on UASI and domestic militarization see the December 2022 report, “DHS Open for Business: How Tech Corporations Bring the War on Terror to our Neighborhoods“ by the Action Center on Race & the Economy, LittleSis, MediaJustice, and the Surveillance, Tech, and Immigration Policing Project at the Immigrant Defense Project.

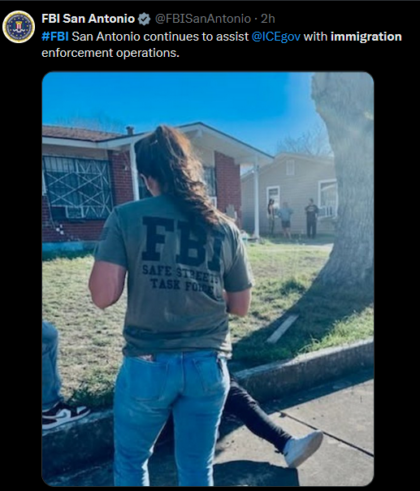

The Safe Streets Task Force (SSTF) is an FBI-led task force system. (Its predecessor system was Violent Crime Task Forces, established in 1992. By 2003, it had transitioned to SSTF.)

In recent days, an FBI social media account posted a photo, apparently with one of their agents wearing a Safe Streets Task Force during some kind of activity at a residence, in reference to immigration. Here is an SSTF MOU between Fort Myers and the FBI (pdf) and the 2021 agenda item (pdf).

There is also some option for deputizing U.S. Marshals although the details are unclear. On May 12, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis (R) claimed that 100 Florida Highway Patrol officers are now “special deputy U.S. Marshals” that can enforce immigration laws themselves. This is connected to a 37-page Immigration Enforcement Operations Plan (pdf) although the role of deputization isn’t specified within.

It’s worth considering how open conflicts between local governments and aggressive federal agencies will affect joint task forces like HIDTA, JTTF and UASI groups. For example, San Francisco police pulled out of JTTF for a time in 2017.

ImmigrationOS: Where is the Data Stored for an “ICE Army”?

Researchers have been watching ICE and other elements of Homeland Security as they work on throwing money at federal contractors, and signaling to them what kinds of projects they should work on. Palantir is extending technologies and loading in records from different agencies across the federal government, and to achieve this project, it could be done probably by extending contracts for the ICE Investigative Case Management system (ICM). Under the ICE TECS Modernization program, ICM replaced TECS-II, which we profiled from a leaked ICE-HSI agent manual in 2019.

Many in the U.S. government have tried to make large databases cross-connected from disparate departments for political ends. These type of super-databases have been considered political hot potatoes since the Watergate era; the Privacy Act was passed in 1974 to force the executive branch to outline the nature of these data systems as well as privacy protection measures. These policies were intended to prevent various abuses, like, say, Richard Nixon using the IRS to go after his enemies list.

Lately, turbocharged data mining has been taking place across the executive branch with ‘DOGE’ teams and contractors like Palantir, which is running a project dubbed ‘ImmigrationOS‘ that is due to be completed in September. (Related contract awards are listed here.)

The October 2021 Requests for Information (RFI) for ICM shows many attributes of the tracking system that Palantir seems to be enhancing (Docs are in the “attachments” section). More about ICM is outlined on the August 2021 Privacy Impact Assessment Update.

Additional ICE RFIs in recent years showed that ICE is interested in “release and reporting management,” which includes tracking devices and “monitoring technology” for people who are not being held in detention centers.

The DOGE teams and Palantir have been working on a “mega API” for IRS records according to WIRED, a new integration that is likely connected to the infamous IRS-ICE agreement.

The IRS-ICE Agreement that Shook Tax Agency Leadership

This IRS-ICE agreement obtained by American Oversight was produced after the acting commissioner Melanie Krause in resigned in April in objection to this agreement. Acting chief counsel William Paul was removed and replaced with Andrew De Mello to force this through as well. Why so much resistance from the top levels?

After Watergate, the Privacy Act was passed to constrain the use of “systems of records” for law enforcement and other purposes. This MoU tries to give assurances that everything will be handled by trained personnel. American Oversight says “the MOU fails to include any meaningful independent oversight of when and how the information is to be shared, relying on internal compliance and self-reporting and raising questions about how the public can ensure the government is following its own rules.” It showed the government redacted that the IRS would disclose “address information” of taxpayers to ICE, but the court forced these passages to be released.

“Project Homecoming” and Expanding Domestic National Guard Activity, via 287(g)

In a May 9 “proclamation” from the White House entitled “Establishing Project Homecoming,” buried at the end is yet another expansion of armed force in the works.

“[…]the Secretary of Homeland Security shall supplement existing enforcement and removal operations by deputizing and contracting with State and local law enforcement officers, former Federal officers, officers and personnel within other Federal agencies, and other individuals to increase the enforcement and removal operations force of the Department of Homeland Security by no less than 20,000 officers in order to conduct an intensive campaign to remove illegal aliens who have failed to depart voluntarily.”

White House, “Establishing Project Homecoming,” May 9, 2025

In our research we found that the National Guard state agencies in Florida and Texas are already approved by ICE for the 287(g) task force model. Thus, the National Guard would not have to be “federalized” to do more operations for the feds, it could just use 287(g). Likewise, CNN reported the Guard units could be under state authority, not federal Title 32 mobilization. As the Brennan Center explains, National Guard personnel managed by their governor and adjutant general are not subject to the limitations of the Posse Comitatus Act.

It appears some of the militarized machinery here involves the concept of “force protection” as a way to coerce state and local governments to cooperate with the immigration crackdown, as liberal news site Talking Points Memo noted. An ominous release from the U.S. Army on April 15, “Joint Task Force Southern Guard protection cell secures the mission” describes how military “force protection” assets “address every possible security and safety scenario in support of a Department of Homeland Security (DHS)-led illegal alien holding operation (IAHO).” Southern Guard has been a very expensive operation to dump migrant detainees in the Pentagon’s offshore base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; it is led by U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM).

Based in Fort Huachuca, Arizona, since March, the Joint Task Force-Southern Border (JTF-SB) group is led by the U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) which was created in 2002 as the military’s counterpart to the Department of Homeland Security. [See our previous stories looking at NORTHCOM and protest management at major events.]

Tension in Newark; Additional Detention Centers Sought for ICE Operations

Recent days have been tense in Newark, New Jersey, with an ICE detention facility called Delaney Hall going into operation. Newark Mayor Ras Baraka was arrested at the facility Protests transpired in the aftermath of Mayor Baraka’s arrest. ICE facility inspections are specifically mandated as a power for members of Congress (pdf). The DOJ charged a Democratic member of Congress, Rep. LaMonica McIver (Newark), who sought to inspect the facility, with felony assault. On May 21, U.S. District Court Magistrate Judge Andre Espinosa reprimanded federal prosecutors who charged Baraka, then officially dismissed the charges.

On May 1, a federal lawsuit was heard in which New Jersey is trying to block all privately operated immigration prisons, with the state arguing it can control the private prison market, overriding the federal government’s hope to run a large facility in the region that it desperately needs to scale its mass detention and deportation agenda.

Since 2024 more signs have turned up that ICE is trying to expand its network of detention centers, a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit by the ACLU found (Case No. 24-cv-7183). New Jersey and GEO Group detention center capacity was exposed as well, alongside more information about the North Lake Detention Facility, “a previously vacant facility in rural Michigan that will soon serve as the one of the largest ICE detention hubs in the Midwest.”

ICE faces significant logistical constraints in its archipelago of detention centers. A large set of centers in Louisiana, with many reports of neglect and abuse, is central to the system. Researchers have recently found a new way to calculate how many people are detained in these facilities.

Report: Project 2025 Working Group Proposed Huge Police Command Network Under White House Control

A new report by Beau Hodai for Phoenix New Times/Cochise Regional News introduces elements of a major plan by the previously unreported Project 2025 Border Security Work Group, which offers some vision for a vast expansion and centralization of policing in the United States. Project 2025, a “900-page policy ‘wish list’,” was developed by several conservative think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation to guide Trump Administration policies in a more focused fashion than the first term. The plans, developed by September 2024, include both a security policy and a propagandistic “strategic communications plan” to convince the American public that dreaded “terrorists” are loose in the land and only their extreme policies can save the day.

Hodai writes, “several of the policy proposals contained in the documents have already been executed,” including the IRS policy, dumping immigrants in Guantanamo, militarizing the U.S. border, and widespread revocation of immigrant parole programs and other legal status cancellations. Many “lines of operation” are proposed in the documents, and four new tiers of command controlled ultimately by the White House: Regional Command, State Command, District Command and one Headquarters Command.

In addition, Hodai found that “documents contemplate waiving 287(g) training requirements for sheriff’s deputies and municipal police working in ‘regional command’ units,” because watching 40 hours of training videos is apparently too high a bar to cross. Not surprisingly, the documents also “contemplated invoking the Insurrection Act” and “mobilization of up to one million troops to aid in proposed domestic security operations.”

Plugging leaks in this apparatus would be a serious program as well: “An active counter-intelligence effort must be organized, integrated across all levels, and actively conducted to identify and prosecute any individuals working for and providing classified or operationally sensitive information on border security plans and activities.” More details about these documents are expected to be released in the coming weeks.

A report in The Nation on May 30, 2020, showed that the classified network SIPRNet was used to manage some military planning during the George Floyd Uprising. People with access to anything classified on SIPRNet would risk much greater criminal penalties by sharing documents with politicians that don’t have security clearances.

All of these subjects can seem a bit overwhelming, but it is worth keeping in mind that the building blocks of this political situation were put in place more than two decades ago, after the September 11 attacks.

Many groups are working on opposing different aspects of the immigration crackdown, including by obtaining evidence of the policies, filing lawsuits, seeking injunctions, and challenging the vast levels of spending pouring out of the executive branch.

Cover image and compositions by Dan Feidt. Elements include: claw hammer by Rwibutso Aime; cyberpunk apartment by Leartes Studios; ICE agents photo via Wikimedia Commons; Stephen Miller via DHS / Flickr.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: