South Africa Ranks as World’s Most Unequal Nation

Durban, South Africa – South Africa remains the most economically unequal nation on Earth, that is according to a recent report from the Washington D.C. based World Bank, an international financial institution which “provides loans and grants to the governments of low-and middle-income countries.”

Both the World Bank and its twin brother, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have garnered a notorious reputation for using these loans as leverage to privatize or otherwise take over weaker nations’ economies. Many of South Africa’s senior leadership in the African National Congress (ANC) are well aware of this reputation and have thus rejected all IMF/World Bank bailout proposals.

Unlike most nations which the IMF/World Bank issue loans to, South Africa’s ‘developed’ economy has given it just enough financial reserves to resist these proposals. Despite this initial rejection, the IMF/World Bank are no strangers to the country; since the democratic transition in 1994, they have provided over $9 billion dollars in loans to South Africa.

The IMF’s first loan to post-Apartheid South Africa came on the heels of negotiations between Nelson Mandela’s ANC party and the racist Apartheid government. In exchange for control of the government, the ANC conceded many of its key economic demands, allowing ‘white-minority capital’ to resume its overall command of the economy. In return, the new South African nation was gifted with a $850 million dollar IMF loan. The IMF would go on to successfully lobby Mandela to agree to yet another conditional loan, which was then vetoed by his own party. The ANC’s resistance to any further IMF/World Bank loans would see the country refuse all subsequent IMF loan proposals, that is, until the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the immense and ongoing financial burden caused by the pandemic, South Africa initiated negotiations with the IMF, where the latter agreed to supply the country with an unprecedented $4.3 (R63BN) billion dollar loan. The World Bank would follow up with its own COVID-19 loan, agreeing to a $750 (R11BN) million dollar loan in January of this year.

However, this wasn’t the first time that the World Bank provided a loan to South Africa’s public sector. In 2010, the World Bank loaned around $3.75 (R54BN) billion to the struggling state owned energy giant ESKOM bringing the country’s total current debt to these institutions to around $8.8 (R130BN) billion dollars. (The World Bank project info page is here.)

Check out our in-depth report on ESKOM and the ongoing ‘South African energy crises’

Both the government and IMF have been vague on the exact conditions on these loans. Nevertheless, the government has signaled to the IMF that it remains committed to “structural reforms” as it continues to privatize and deregulate several key economic sectors through what it calls Operation Vulindlela. These reforms include:

- Deregulation of the nation’s public transport system and ‘Corporatization of the ‘Transnet National Ports Authority’ which manages the country’s seaports,

- Deregulation of the public electricity sector and financial “restructuring” or privatization of ESKOM,

- Privatization and deregulation of the country’s digital and telecommunications networks,

- Deregulation of public water sector and water use licenses in such a way that “both protect water sources and meet the needs of investors.”

The Causes of Inequality

For more than 300 years (1652-1961) South Africa existed in some form or another as a European colony, first established by the Netherlands in 1652 and later taken over by the British in 1795. Like all European colonies it was designed primarily for the economic benefit of a small ultra-wealthy European elite, generally at the expense of the native population which were largely enslaved and forced to work on plantations and mines. If there was not enough native labor to work the mines and fields then enslaved or “indentured servants” were brought in from other conquered lands to fill the gap.

This deeply exploitative and racist history, combined with South Africa’s exceptional natural and mineral wealth, resulted in the country becoming the highly diverse, wealthy and economically unequal nation it is today.

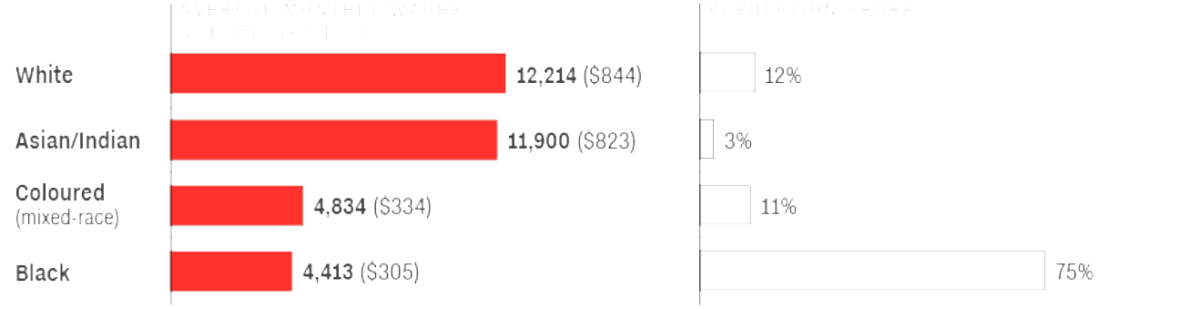

Though the country officially ceased to be a colony in 1961 and only recently ended the white supremacist Apartheid system in 1994, wealth inequality between the rich and poor is still just as bad as it was during the Apartheid/Colonialist era. And though state-sponsored affirmative action programs has produced some upward mobility for Black people, recent statistics show that on average whites still make three times what Blacks make in a month.

Government Response: Promoting ‘Black Economic Empowerment’ and ‘Social Entrepreneurship’

Government and financial institutions have long acknowledged this longtime racist, colonial past and the impact it has had on the region and indeed the world. There is much less agreement on what steps need to be taken to solve the issue.

The ANC-led government has attempted to bridge the racial/class economic gap by promoting its policy of ‘Black Economic Empowerment‘ (BEE), which is similar to affirmative action policies in the U.S. Under BEE, companies operating in South Africa are heavily incentivized to hire and promote Black people within the company. The more Black people a company has involved within it’s workforce and ownership, the more financial government incentives they stand to gain.

This policy has however come under intense criticism from both elements of the political right and left who see the preferential treatment given to certain companies over others as enabling state corruption. Critics also point to the issue of ‘tokenism’ where Black people are promoted as faces of the company but in effect have very little, if any, actual institutional power.

One proposed solution which all parties appear to agree on revolves around the concept of ‘social entrepreneurship.’ Unicorn Riot spoke with ‘Nokubonga,’ a social entrepreneur and student at the Durban University of Technology (DUT), who also works as a tutor in social entrepreneurship at a Durban girls secondary school.

When asked what social entrepreneurship means to her, she explained, “It’s about using our entrepreneurial opportunities and skills to become change agents within the society, and as well as dealing with social issues that impact us in the country.”

When describing how she became a social entrepreneur, she said that she came from a “disadvantaged community” where levels of financial opportunities were sparse and unemployment is high. As a result she decided to form her own events company at the young age of 18 to serve as a economic opportunity and career not only for herself but also for others in her community.

“I was creating a platform, not only for myself, but for people in my community […] and I felt like we need something like that in each and every community. So if I’m into construction, let us all come together and see what we can do, as people who have a passion for construction. If we do that, for each and every industry, I [feel] like the unemployment rate could be a lesser percentage [than] it is now.”

Nokubonga

When asked about whether social entrepreneurship programs would be enough to solve South Africa’s economic issues Nokubonga was uncertain but emphasized that:

“My ideas and what I could run as a social entrepreneur, are different from what someone else is thinking. So if you collaborate all of those projects, I’m definitely sure all of those projects could change the social economic status.”

Nokubonga

Nokubonga said she plans to use her position as a local business leader to invest in a community center that will enhance young people’s skills in order to form their own businesses.

A profile of South Africa’s political parties

The ‘Shack Dwellers’ Fight For Decent Housing

“There Shall Be Houses, Security And Comfort!” or so goes the famous demand from the Freedom Charter, a foundational document which the ruling party ANC helped to craft over 66 years ago. Yet, 28 years after the fall of Apartheid, a quarter of the country’s urban population (roughly 5 million people) still live in informal settlements or ‘shacks’.

In response, some within those settlements have taken on the task of not waiting for state and corporate assistance and have begun organizing their own local poverty relief. Though there are many groups involved in this work, the single largest, and most well known, is an organization known as Abahlali baseMjondolo (Zulu: People of the shacks).

AbM came together in 2005 after a major protest organized at the ‘Kennedy Road‘ informal settlement in Durban, a settlement which has a long and storied history of resisting state attempts to evict its residents.

When the ANC initially came to power in 1994, it promised to improve the conditions of informal settlements like Kennedy Road. As time went on however, very little was actually done to improve conditions. Tensions reached a boiling point when the residents of Kennedy Road blockaded the nearby N2 highway, engaging in a fierce battle with members of the South African Police Service (SAPS).

The protest was launched in response to the private redevelopment of land which had initially been promised to Kennedy Road. Though few of the protesters demands have been met, the Kennedy Road protests were instrumental in bringing people together from other informal settlements, hence the AbM was formed.

In addition to organizing resistance to government evictions and maintaining the demand for decent housing, AbM has also organized numerous land occupations or ‘land reclamations’ in Cape Town and Durban along with a number of mutual aid projects focusing on improving access to food, electricity and water in the settlements.

For these efforts, the group has become the focus of an intense and ongoing campaign of government repression. This state sponsored violence has so far resulted in hundreds of AbM members being arrested, and or subjected to various forms of physical/psychological abuse, harassment and imprisonment. Dozens of AbM organizers have also been killed, either explicitly by state officials, or under suspicious and unsolved circumstances.

AbM of course isn’t the only formation of its kind. There are dozens of municipal, provincial and national organizations dedicated to representing the interests of the informal settlements.

For this report, Unicorn Riot also spoke with ‘Kenneth,’ a member and political organizer with the Western Cape based “Housing Assembly” which describes itself as “a social movement of people representing over 20 different communities in the Western Cape, South Africa.”

Kenneth is from an informal settlement in Cape Town known as ‘Barcelona’ which was first established in 1990 by residents from the nearby ‘Gugulethu’ township. While he acknowledged some similarities with other groups like AbM he also pointed out what makes Housing Assembly different:

“There’s a lot of organizations that do similar work, but I think there’s one thing that sets us apart from the other organizations and it’s the fact that housing assembly operates in more than one housing type. […] Some of our work is in RTP [government subsidy housing], some of the communities are temporary relocation areas in which people got evicted or fires or any disaster and then got relocated by the state. Some people are backyard tenants [living] in other people’s yards.”

Kenneth, Housing Assembly

When asked about the future of the movement and what steps his organization is taking in getting more housing for disadvantaged people, he explained that policy change was key:

“To get people [into] houses, we have a variety of ways of seeing [how] this might happen and we see the first is affordable housing. Another is to minimize the number of evictions that are happening because although they’re happening in different pockets, put together it feels massive, and then prioritize [children] and disabled people and so on.”

Kenneth, Housing Assembly

He also said that Housing Assembly will continue pressuring the government to continue building more low income housing, despite ongoing issues with the quality and the ways in which they are being built.

“But as it [is] right now, we have to fight for the state to continue to give [these] RDP houses although they are so badly built, you know, built on the outskirts of the city, they are built with cheap material on cheap land. Tenders are given to small construction companies [that] cut corners.”

Kenneth, Housing Assembly

Conclusion

Despite the loans from the IMF/World Bank being intended to help in stemming the economic recession, it is worth noting none of the funds have been specifically dedicated to housing relief. Though government has indicated that the much of this money will be used for poverty relief programs such as the COVID relief grant (which offers qualifying citizens R350 a month) In fact much of the money is also simply being used to manage the country’s growing debt.

State officials have countered that the loans were necessary in order to “contain” South Africa’s rising debt expenditure; unlike previous loans, these are low interest loans that are largely “unconditional.” Yet both the IMF/World Bank and South African government have indicated that they are committed to “economic reform” which includes ongoing public sector cuts in wages and other worker benefits.

As a result, most within South African’s massive and influential labor union sector as well as elements in the ANC and the entirety of the Economic Freedom Fighters party (EFF) have rejected these loans on the basis that they will ultimately wind up worsening poverty in the region. (Learn more about the EFF and other South African political parties here.)

Issues relating to state corruption also fuel questions over whether this COVID relief money will actually reach affected communities. Nevertheless, the government is expected to begin the process of repaying these loans in 2023.

Unicorn Riot’s South Africa Coverage:

- #FeesMustFall – South Africa’s Student Movement for Free Education - March 19, 2023

- South African Military to Guard Power Stations After Record Power Outages - December 29, 2022

- Union Infighting Threatens to Derail South African Workers Movement - December 9, 2022

- South African Water and Electricity Supply Crises Grow After Deadly KZN Riots and Floods - July 19, 2022

- South Africa Ranks as World’s Most Unequal Nation - April 8, 2022

- The End of One Party Rule in South Africa: A Profile of South Africa’s Political Parties - March 9, 2022

- Durban Warehouse Fire Leads to Chemical Leak and Criminal Investigation - November 21, 2021

- Over 212 Dead and 3,400 Arrested as Protests Rock South Africa - July 19, 2021

- ESKOM and the South African Energy Crises - December 9, 2020

- South African Unions Form Alliance Against Government - October 20, 2020

- Coronavirus, Corruption, and Resistance: Life Under South Africa’s Lockdown – August 17, 2020

- South Africa Under Lockdown As Covid19 Spreads – March 29, 2020

- Reclaiming Space in South Africa: I.D Green Camp Gallery - January 6, 2020

- Far Right Racists Push Fake South Africa White Genocide Narrative - August 23, 2018