The End of One Party Rule in South Africa: A Profile of South Africa’s Political Parties

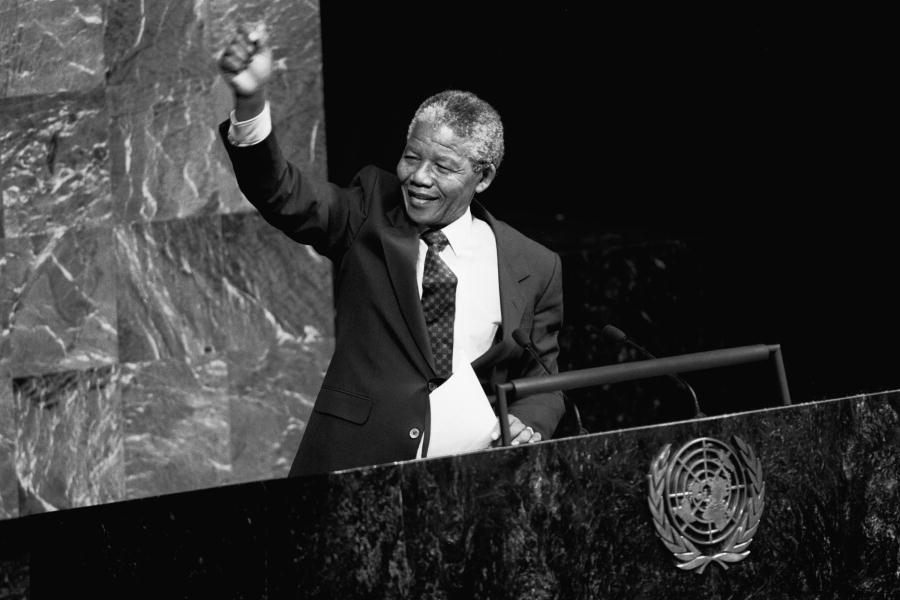

Durban, South Africa – Since the early 1990s South Africa has undergone the process of deconstructing the racist segregationist legacy of Apartheid. It was at this time that the anti-apartheid movement, broadly represented by Nelson Mandela and his political party in the African National Congress (ANC) began negotiations with the South African government to peacefully end Apartheid. On the other end was the white supremacist National Party (NP) led by F.W. De Klerk and various international capitalists hoping to preserve at least some of their institutional power and economic privileges. Both sides would eventually reach an agreement in 1993, leading to South Africa’s first ever, all-inclusive democratic elections.

For these efforts Mandela, and by extension, the ANC had gained an almost mythical reputation within large sectors of South Africa’s predominantly Black working class, a status which they have used to dominate every single democratic election since the end to Apartheid nearly 30 years ago. South Africa has thus gone from being an authoritarian one-party state, controlled by the National Party (NP) to being a de-facto one-party state controlled by the ANC.

Despite the ANC’s firm grip on the executive and legislative branches, South Africa has always maintained a wide range of diverse political parties each with their own positions and internal/external conflicts. Nonetheless, since 1994, no party has ever stood a real chance at challenging the ANC in elections.

Yet, years of financial mismanagement, numerous corruption scandals and overall failed promises have weakened and divided the steadily aging ANC. As a result opposition parties are progressively gaining ground. This report briefly profiles the history of ANC, its political competition in South Africa and what the radically new political landscape may mean for the future of the Republic of South Africa.

The African National Congress

Widely recognized as the oldest National Liberation Party in Africa, the ANC was formed in secret over 110 years ago in 1912 in the Free State provincial capital of Bloemfontein. The party was formed in response to the overtly white supremacist and segregationist government policies overseen by the country’s all white parliament.

The ANC would go on to craft an alliance with other anti-apartheid organizations via the Congress Alliance (CA). The CA included organizations such as the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SAFTU) as well as the South African Indian Congress (SAIC) among others. This alliance would be responsible for crafting a collaborative document which would clearly define their collective grievances and demands. That document would be titled the ‘Freedom Charter’ and would later serve as a major influence on South Africa’s current constitution.

Initially the ANC adhered to a strict policy of only using non-violent protest, designed to bring concessions out of the Apartheid state. These non-violent efforts were met with severe state repression by the South African security services as many ANC and other anti-apartheid activists were systematically jailed, killed or forced on the run. This repression caused the ANC to abandon its strict adherence to non-violence, forming a paramilitary wing, “uMkhonto we Sizwe” (Zulu: “Spear of the nation”) otherwise known as ‘MK’ in 1960.

The South African state escalated its repression against the ANC by arresting most of its senior leadership in the early 60s including Nelson Mandela, who would wind up imprisoned on Robben Island for over 27 years. Despite these heavy blows, MK would continue low intensity guerilla war against the white supremacist South African government for more than 30 years. In 1984, the ANC would also be pressed into armed conflict with one of its former allies turned bitter rival, the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).

The Inkatha Freedom Party

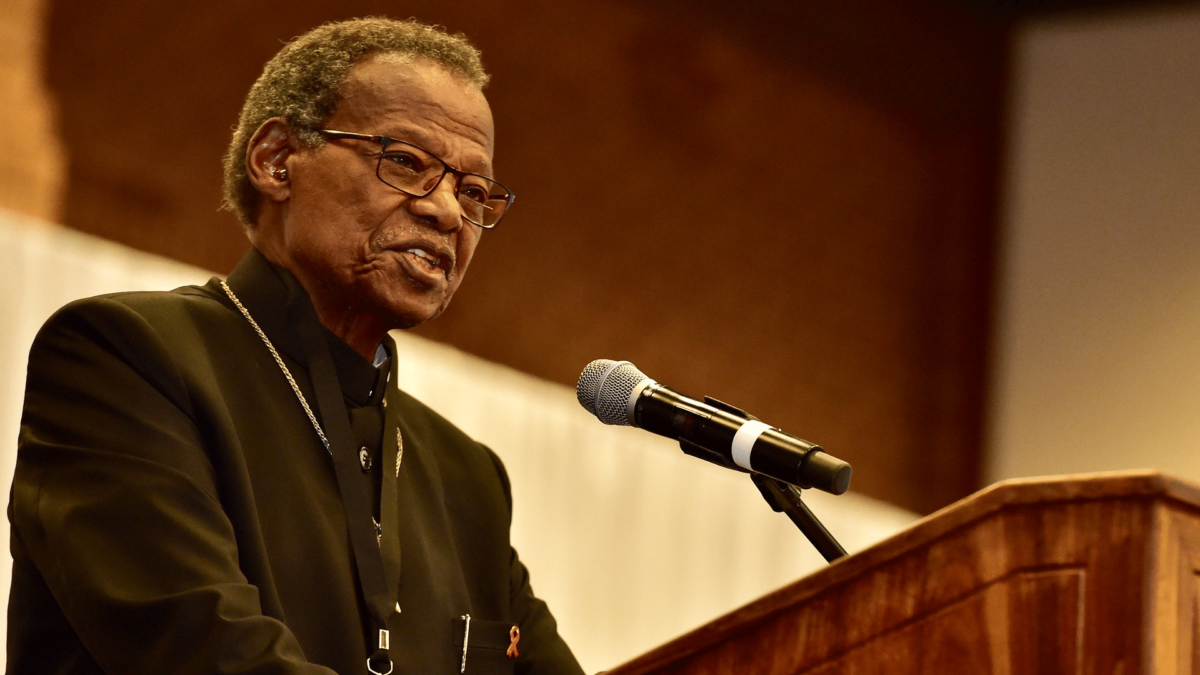

“Inkatha” is a Zulu word which roughly translates to “grass coil”. The word refers to a sacred royal artifact in the form of a tightly wrapped grass coil which is meant to symbolize “the unity of the Zulu people”. The last known Inkatha was possessed by King Cetshwayo ka Mpande and was reportedly destroyed by British forces during the 19th century Anglo-Zulu War. The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) is thus primarily influenced and tied to the modern day Zulu monarchy via its founder, and royal head of the Buthelezi clan, Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi.

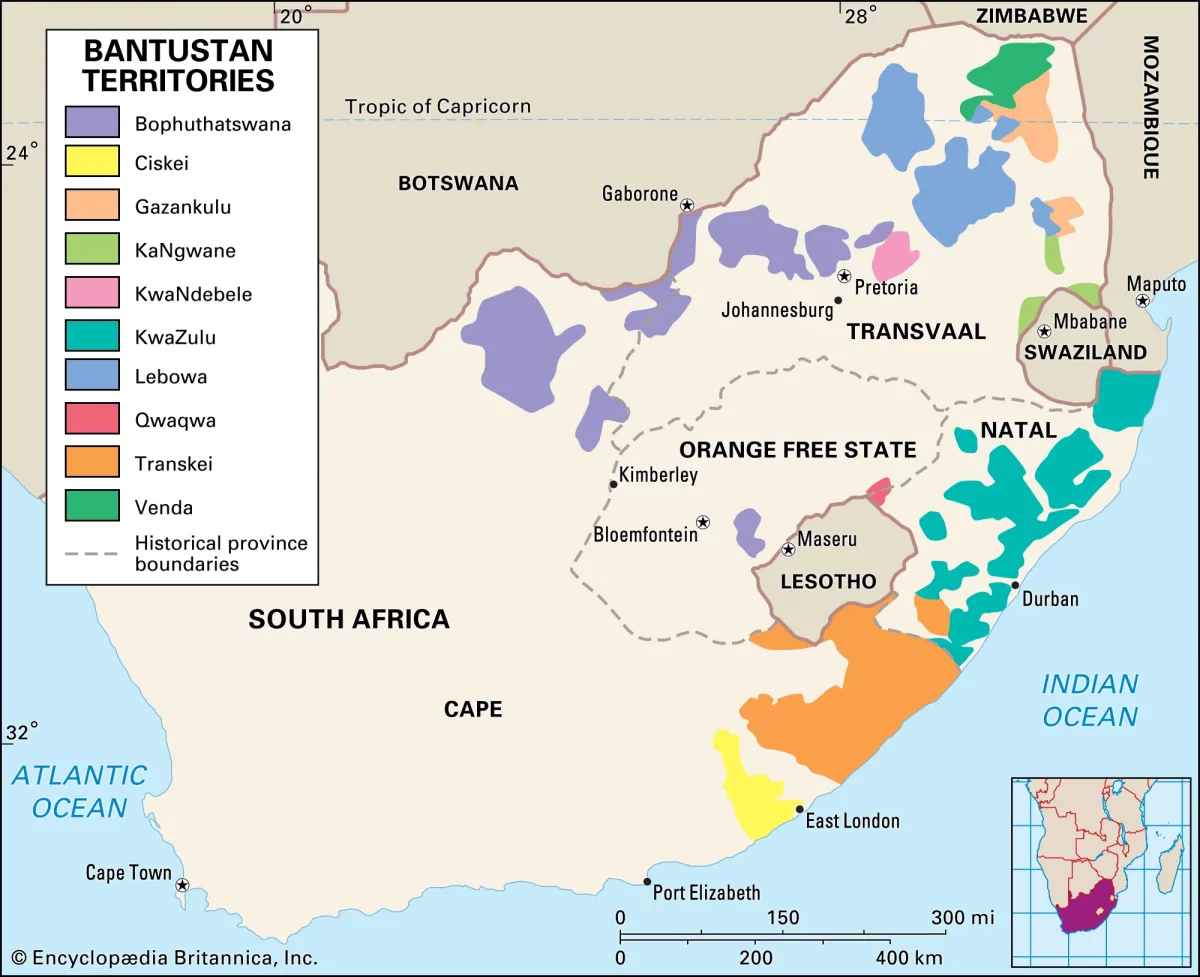

The IFP was established by Buthelezi in what was then known as the “Bantustan of Kwazulu.” Bantustans were areas designated by the Apartheid state for South Africa’s predominantly Black population. The government gave limited “independence” to local tribal chiefs in these heavily divided and territorially ambiguous areas. In turn, Black people were denied official South African citizenship and required government issued passes if they wished to travel outside the Bantustan.

As such, Kwazulu was designated by the Apartheid state as the official homeland for the Zulu people, the largest single ethnic group in the country. Despite the limited “autonomy” granted to Zulu chiefs, the borders and administration of Kwazulu ultimately fell under the wider “Natal Province” which was exclusively governed by its local, predominantly English-speaking white population.

Like most founders of the IFP, Buthelezi held deep ties to the ANC as he was an early member of the ANC youth wing (ANCYL) while studying at the University of Fort Hare in 1949. He was later expelled from that university for participating in a student boycott, but claims that he later earned his full bachelors degree (BA) in “history and bantu administration” from the University of Natal at an unspecified date.

In 1970, Kwazulu tribal authorities appointed Buthelezi as the “Chief Executive Officer of Kwazulu” thereby cementing his position as head of the tribal government in Kwazulu. Buthelezi would go on to lead the Kwazulu Bantustan for the next 24 years right up the abolishment of the Bantustan system in 1994.

Due to their shared history and Black nationalist politics, Buthelezi and the ANC initially maintained good relations. However, the relationship began to sour as the ANC grew ever-closer to the Soviet Union and its allied South African Communist Party. (SACP)

As the ANC’s war against the state intensified, the Soviets provided increasing amounts of economic assistance and military aid to the ANC. This left a profoundly bad taste in Buthelezi’s mouth as he and his party preferred peaceful negotiations with the Apartheid government in order to re-establish the absolute rule of the royal Zulu monarchy. The IFP thus had no interest in war with the South African state and was especially opposed to the ANC’s egalitarian, communist and secular ideals.

This ideological tension would eventually lead to the IFP’s official split from the ANC in 1979, a split which would later boil over into open warfare between the two parties between 1984-1992. During this war, the South African Self Defense Force (SADF) was documented supplying IFP militias with military training and weapons to be used against the ANC and other anti-apartheid organizations in Kwazulu in what they coined “Operation Marion.”

Though the IFP-ANC conflict in Kwazulu would eventually end in 1992, the permanent scars left behind in the almost decade-long conflict are still present in the minds and bodies of those who survived.

Unicorn Riot spoke with Phumlan Hlophe, a Zulu resident of the Umlazi township who experienced the IFP-ANC political violence late early 90s:

“I lost school time during 1990 because after Mandela was released there was mass violence. One of my friends died when we were attacked inside the school during school hours where the other students who belonged to the IFP were told not to come to school that day and we [ANC students] went to school without being aware. Then the Zulu Police [IFP] would come in numbers and attack us with tear gas and rubber bullets. We were scattered and whoever could survive, could survive.”

– Phumlan Hlophe, Umlazi Township resident

To this day the IFP maintains a significant political support base in Kwazulu-Natal, especially the rural areas. Though it pales in comparison to ANC support in the urban centers, the IFP remains an important player in the regional politics of Kwazulu-Natal.

The Democratic Alliance

Of all the opposition parties, perhaps none have been more successful so far than the Democratic Alliance (DA). The DA traces its roots back to the Progressive Party, a liberal political party established in 1959, which represented the liberal white opposition to Apartheid, in the country’s then all-white parliament.

The modern day DA however was officially founded more recently in the year 2000. The majority of its support base comes from middle/upper class whites typically aged 35 and up who hold broadly liberal, conservative, or “centrist” views.

DA politicians frequently put the blame squarely on the ANC for much of the country’s core issues such as high crime, corruption and mass unemployment. This message strongly resonates with their white liberal-conservative base which has always been wary of the ANC’s land redistribution proposals, and racial equality programs.

However, the DA has struggled to shed its privileged white image and connect with younger Black South Africans. It has also been criticized for its known connections with far-right white nationalist organizations. Nonetheless, the DA has experienced modest yet steady growth since 2000, and maintains a particularly strong base of support in the city of Cape Town — the only city where it dominates the local city council.

The DA’s slow and steady growth came to a halt however in the 2019 national elections, and for the first time ever the party lost votes. This is at least partially due to the increased competition it now faces from it’s radical right-wing affiliate turned competitor, in the white nationalist Freedom Front Plus. (FF+)

The Freedom Front Plus

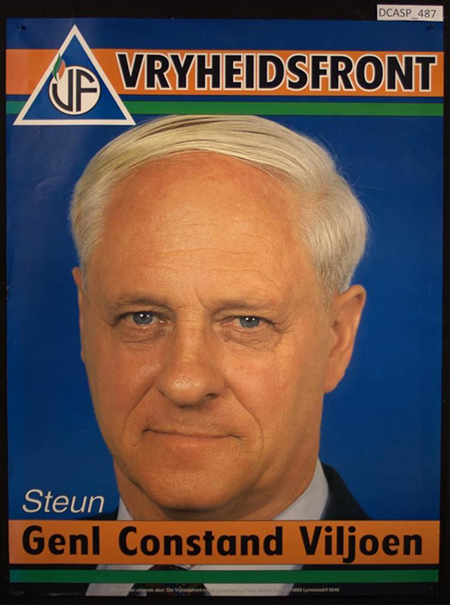

The plan to pivot South Africa away from Apartheid colonialism into the new era of the “Rainbow Nation” was not universally accepted by all. In response to the what they saw as a betrayal by the National Party, many reactionary white supremacists split off from the NP and began organizing to stop the 1994 elections and continue their war against the ANC.

In preparation for this planned civil war, four high ranking SADF generals would form a right-wing umbrella-party called the Afrikaner Volksfront. (AVF) One of the four generals was Constand Viljoen, who just prior to 1994, was said to have personally commanded some 50,000 – 60,000 paramilitary soldiers. In the event that the AVF’s goal of stopping the election failed, this paramilitary force would be ready to initiate a renewed civil war against the ANC.

However, the AFV’s disastrous attempt at military intervention in the Bophuthatswana crisis coupled with the success of the 1994 elections contributed to Viljoen’s apparent change of heart as he decided to enter into politics instead, hence founding the Freedom Front. (FF)

From the very beginning of its existence, the FF knew they had no chance of beating the ANC in truly free and fair elections, so they transitioned away from their previous goal of maintaining the racist Apartheid system towards the creation of a separate “Volkstaat” (people’s state) or a fully independent white ethnostate.

Opinion polls conducted between 1994-1996 revealed that a majority of Afrikaners were opposed to the Volkstaat concept. Nevertheless, the party exceeded political expectations, garnering around 2% of the total vote (424,555 votes out of 19,726,610 total votes cast) which made it the fourth largest political party in the country at the time.

The following decade, however, would see FF’s election numbers steadily decline, eventually forcing it to enter into a merger with the fellow white nationalist Conservative Party and Afrikaner Eenheidsbeweging to become the “Freedom Front Plus” (FF+) in 2003.

The FF+ has since expanded its target audience beyond its small extreme right-wing, white-minority base, by now claiming to represent “all minority people” in South Africa, or more specifically members of the mixed-race “Coloured” community, many of whom also speak the Afrikaans language.

This policy shift is at least partially responsible for the party’s resurgence as that same year, during the national and provincial elections, it won a record 11 seats in parliament. The new influx of Afrikaner/Coloured voters was mostly made up of those who had previously voted for the Democratic Alliance, in particular, voters from Cape Town and the surrounding Western Cape province. The Western Cape is the only province in South Africa in which Coloured people are the majority ethnic population. As a result both the DA and FF maintain a significant base there.

In 2019, the FF endorsed “Cape Independence as a policy aim of the party” which seeks the complete independence of the Western Cape along with certain portions of the Eastern/Northern Cape as well as portions of the Free State from the Republic of South Africa.

In 2021, the DA joined the FF in formally endorsing the Cape Independence movement and has even made plans to separate the western Cape’s electricity grid away from the state energy monopoly ESKOM.

The Economic Freedom Fighters

On the opposing side of the FF’s far right politics is the radical left-wing Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). Founded in 2013 by former ANC Youth League president Julius Malema, the EFF is currently the largest split-off from the ANC and is the second largest opposition party next to the DA.

Julius Malema, was born in 1981 to a single working class mother in the Black township of Seshego in modern-day Limpopo. At the time of his birth, Malema’s hometown was the capital of the former “Bantustan of Lebowa,” an area designated for the Pedi ethnic group (which Malema belongs to). Malema began his political career early when he joined the ANC’s youth league at the young age of 9. Recounting his early days in the ANCYL, Malema states that one of his primary responsibilities was to “take down political posters belonging to the National Party.”

At around age 13, Malema was given paramilitary firearms training, a common rite of passage for male youth in the ANC during the days of the underground war. Ultimately, it was not his skills with firearms but rather his talent as a public speaker and charisma that would see him rise through the ranks of the ANCYL, eventually becoming president of the youth league in 2008.

Known for his brash and populist speaking style, Malema has made many friends and enemies alike. One of those friends-turned-enemy is the now deposed and former South African President, Jacob Zuma. An early supporter of Zuma’s populist land/wealth redistribution policies, Malema’s loyalty to Zuma was at one time so great that he publicly stated “We are prepared to take up arms and kill for Zuma”.

However, following Zuma’s ascent to the presidency, Malema’s increasing reputation for confrontation and controversy began to alienate even his own superiors in the ANC. The fallout eventually reached a head in 2012 when Malema was expelled from the party for making comments that according to an internal ANC disciplinary review, “sought to portray the ANC government and its leadership under President Zuma in a negative light in relation to the African agenda.”

The following year in 2013, Malema and his followers would go on to form the EFF, the first ANC splinter party since the end of the Apartheid regime. Unlike most other political parties, the EFF is unique in that it does not limit itself only to electoral politics. It has become well known for its many publicized mass actions in the streets, protesting a wide range of alleged corrupt wealthy businesses and institutions they see as racist.

While the EFF also suffers from internal party conflicts, they have maintained a steady position as South Africa’s third strongest political party only behind the DA and the ANC. This political status is maintained by a well-organized, determined and young support base, particularly students between the ages of 18-35. Nevertheless, some former members of the party say numerous internal issues related to the authority concentrated in Malema’s hands has limited its true potential.

“I love Mr. Malema, but when we when we start calling him and referring to him as commander in chief that does something to him, it does something to us, you know, so we should all be commanders and chiefs to some degree. Of course [we should have] an elect that will say, because we trust you with this responsibility that we all have, then you can represent that because we can’t all the millions of us be there to talk. But you can’t be the commander and the chief.”

Sibusiso Tshabalala, student and former EFF member

Future outlook

As the ANC’s grip on power continues to slide, it is now becoming clear that it isn’t a question of if, but rather when they may cede majority control of South Africa’s national government. The recent 2021 municipal elections showed more evidence of this trend: for the first time ever, the ANC share of the vote dipped below 50%.

As South Africans increasingly look towards more radical parties to solve the nation’s problems. The real question becomes whether or not these wildly different political forces can cooperate well enough to form an effective coalition against the ANC and form a stable government. Though history has shown that the odds of this happening are low, the continued unity of what the late anti-apartheid activist, Bishop Desmond Tutu, once coined the “Rainbow Nation” may still depend on the answer.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Unicorn Riot’s South Africa Coverage:

- #FeesMustFall – South Africa’s Student Movement for Free Education - March 19, 2023

- South African Military to Guard Power Stations After Record Power Outages - December 29, 2022

- Union Infighting Threatens to Derail South African Workers Movement - December 9, 2022

- South African Water and Electricity Supply Crises Grow After Deadly KZN Riots and Floods - July 19, 2022

- South Africa Ranks as World’s Most Unequal Nation - April 8, 2022

- The End of One Party Rule in South Africa: A Profile of South Africa’s Political Parties - March 9, 2022

- Durban Warehouse Fire Leads to Chemical Leak and Criminal Investigation - November 21, 2021

- Over 212 Dead and 3,400 Arrested as Protests Rock South Africa - July 19, 2021

- ESKOM and the South African Energy Crises - December 9, 2020

- South African Unions Form Alliance Against Government - October 20, 2020

- Coronavirus, Corruption, and Resistance: Life Under South Africa’s Lockdown – August 17, 2020

- South Africa Under Lockdown As Covid19 Spreads – March 29, 2020

- Reclaiming Space in South Africa: I.D Green Camp Gallery - January 6, 2020

- Far Right Racists Push Fake South Africa White Genocide Narrative - August 23, 2018