‘Tortuguita Vive’: A No-Compromise Movement Responds to Police Killing a Forest Defender

DeKalb County, GA – The anonymous communique issued in May 2021 was written in romantic prose. Its author describes a nighttime walk through the South River Forest, just south of Atlanta, where “a couple of queers” had discovered seven unattended pieces of heavy machinery parked in the woods. The equipment was staged near the proposed sites of what activists now call ‘Cop City’ and a new sound stage complex being built by Blackhall Studios. For the anonymous people who found these machines, there was no question about what had to be done. The saboteurs destroyed the earth movers, cutting fuel lines, smashing glass and spray painting messages to tell the would-be operators of the machines why they had been destroyed.

The culprits set the machines on fire before disappearing into the night. The statement claiming responsibility for the attack ended with a warning: “Any further attempts at destroying the Atlanta Forest will be met with similar response. This forest was here long before us, and it will be here long after. We’ll see to that.”

This was the first known physical blow against the Atlanta Police Foundation’s (APF) attempts to build a sprawling police training facility and manufactured green space on a 381-acre wooded plot of land just south of Atlanta. In the nearly two years since that anonymous communique was issued, locals in Atlanta and supporters from across the United States have taken up the fights against both ‘Cop City’ and ‘Hollywood dystopia,’ two projects that currently threaten the forested area described as one of the “lungs” of the city for the dense foliage it holds.

A broad and diverse movement has sprung up in resistance to both projects, and local action, bolstered by national and international support, has effectively prevented the construction of Atlanta’s Public Safety Training Facility and stalled work on the new movie studio campus. Through a wide diversity of tactics including everything from preschooler-led art builds and music festivals to militant direct action and sabotage, the grassroots opposition has gained worldwide attention. Anarchists, environmentalists, abolitionists and socialists have taken note of the successful campaigns being waged against the projects, which have come to symbolize the intersections of many struggles.

But as the movement has grown, so too has the state’s repression against people in the fight to defend the Atlanta forest. On January 18, Georgia State Patrol (GSP) troopers shot and killed Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Paez Terán during an armed raid on a protest encampment in Weelaunee, also known as the South River Forest. The killing followed a year and a half of police, prosecutors, and politicians resorting to increasingly repressive measures to punish activists.

Armed raids and politically-motivated domestic terrorism charges have come to characterize the state’s response to the movement. Organizers have long warned about the danger the escalated tactics presented, including the potential for deadly violence at the hands of police. After the warnings became reality last month, those embattled in the fight to defend the Atlanta forest face a new set of challenges.

From its beginning, the movement has been one of no compromise, with protesters vowing that “Cop City will never be built.” The state seems to be responding in kind, pushing forward with the broadly unpopular plan to build the nation’s largest police training facility, resorting to tactics up to and including lethal force against those opposed to the project.

Remembering Tortuguita

On Jan. 18, members of a Georgia State Patrol SWAT team killed 26-year-old Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Paez Terán during an armed raid in Weelaunee, the forested area just south of Atlanta where the city plans to build a $90 million police training compound known derisively as ‘Cop City.’

Since summer 2022, Terán, known to friends and fellow protesters as ‘Tortuguita’, (“little turtle” in Spanish) had been an active participant in the intertwined struggles to defeat the massive police training facility and the new, sprawling sound stage complex set to be built on parcels adjacent to the ‘Cop City’ land. They joined the permanent occupation of the wooded area that the city and private developers plan to raze to complete these projects.

Tortuguita was a nonbinary Indigenous Venezuelan anarchist who relocated to the U.S. and lived in Tallahassee, FL, among other places, before living in the woods nearly full-time. While there, they set up and maintained a section of the camp for those who are queer, transgender, Black, Indigenous, and people of color — protesters who face unique challenges as members of traditionally marginalized and targeted groups. They were committed to seeing ‘Cop City’ stopped and the forest remaining intact, and they put their beliefs into practice, organizers told Unicorn Riot (UR).

“You couldn’t come into the forest without meeting them,” one local organizer told UR on the condition of anonymity. “They were such a part of the social fabric of the forest.”

Friends of Terán who spoke with Unicorn Riot emphasized Tortuguita’s practice of radical love and fierce commitment to building a better world. They coordinated fundraising efforts and mutual aid projects, and acted as a steward for those coming to the forest to join the fight. A trained medic, Terán often traveled to queer and trans gatherings to help support other queer people and organizations using their training and knowledge. According to those who knew them in the movement, they were a complex, unique and thoughtful person who lived by their convictions and brought dedication to their work.

“Tortuguita just had so much compassion for everybody. They saw the humanity in every single person, and they wanted to see a better world,” the anonymous local told UR.

Tortuguita’s killing sent shock waves through the movement and the broader international community of abolitionists, anarchists, environmental defense organizers and civil rights advocates. In the weeks since their killing, Atlanta locals and those in solidarity around the world have responded with grief, sadness, anger, and redoubled determination to stop ‘Cop City.’

Shortly after the killing, people organized vigils in Atlanta, while others across the country coordinated memorials and other shows of support. When Atlanta community members showed up for the first vigil following Tortuguita’s death, on the night of Jan. 18, they didn’t yet know who they were mourning. While everyone knew a protester had been killed that morning, police had not released the name of the victim, and organizers were still struggling to identify who was shot. But the following day, organizers confirmed and announced that it was Tortuguita. The police confirmed the victim’s identity a short time later.

Once confirmed, the sadness and anger already gripping the community was compounded. Outpourings of support came from across the country while those in Atlanta struggled with the reality that police had used lethal force against a forest defender known to so many in the movement.

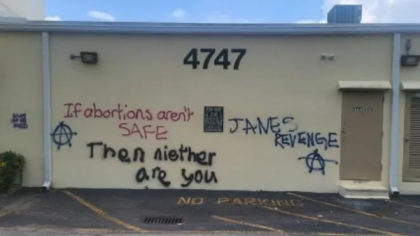

Three days later, a fiery protest took the streets of downtown Atlanta, as people smashed windows at the Atlanta Police Foundation headquarters, destroyed two police vehicles, and damaged storefronts of companies funding APF’s push to build ‘Cop City.’ The militant action sent a clear message: the police killing of Tortuguita would not stop the movement, and those responsible would continue to face consequences.

The death of a forest defender came among what movement participants describe as a clear trajectory of increased violence and repressive action being brought by the state and police. Now that the police have used lethal force against a ‘Cop City’ protester, others in the movement have been forced to confront the ramifications and figure out what to do next. While the terrain has shifted, the determination and no-compromise ethic of the fight to stop ‘Cop City’ remains.

Terrorists or Forest Defenders?

January’s killing fits within a larger context of criminalization of environmental and abolitionist movements that has escalated in recent years. In Atlanta, people organizing against ‘Cop City’ saw this escalation taking root locally, and predicted its outcome well before a Georgia State Patrol SWAT team shot Tortuguita to death.

The community had warned about the risk of police using lethal force for months ahead of Tortuguita’s killing. Marlon Kautz, an organizer with the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, told Unicorn Riot that Tortuguita’s killing, while devastating, was not surprising to those who had been paying attention to police rhetoric and activity over the last two years.

Kautz described what organizers now see as a linear path of increasingly hostile, violent and repressive measures that law enforcement agencies have taken to stop activists in their fights against the police training complex and movie studio, all of which culminated in Tortuguita’s killing on Jan. 18.

On February 25, the Atlanta Solidarity Fund (ASF) and Community Movement Builders, along with attorneys at the Civil Liberties Defense Center and Georgia attorney Donald F. Samuel made an announcement that they expect state prosecutors to charge some activist organizations including ASF as “criminal organizations” under Georgia’s RICO law.

In the movement’s early stages, as people began organizing protests and demonstrations against ‘Cop City’ and the DeKalb County land swap, police made arrests on minor charges, such as accusations of being in the street illegally. The first round of arrests came during a 2021 demonstration outside a city council member’s home while the city voted to approve a land lease between the city and the Atlanta Police Foundation. Eleven people were arrested and reportedly charged with “pedestrian in the roadway” violations.

Opposition grew as locals and supporters carried out home demonstrations and other protests, and police response escalated to include increased surveillance of protesters through tactics like visiting organizers’ houses and issuing arrest warrants to bring in people actively opposed to the project, Kautz told Unicorn Riot.

But the movement continued to pick up momentum and national attention as opponents set up permanent occupations inside Weelaunee to block construction from starting. Police responded with more hostility. A series of raids in the woods, aimed at clearing out protesters and their camps, began in late 2021 when local police and DeKalb County employees evicted an encampment in the South River Forest.

Protesters in turn doubled down in their commitment to stop the project. Across the country, a decentralized movement against ‘Cop City’ grew to target contractors and funders who are aligned with the Atlanta Police Foundation or other aspects of the project. Solidarity actions began popping up in New York, Minneapolis, Portland, and elsewhere as others watched the struggle unfolding in Atlanta.

The state was watching, too. Over the course of 2022, police raids increased in intensity and frequency as Georgia assembled a multi-jurisdictional task force made up of local, state and federal law enforcement agencies to counter the rapidly expanding movement. The task force, which includes members from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, Atlanta Police Department, Georgia State Patrol, DeKalb Police Department, FBI, and multiple prosecutors’ offices, was mobilized as a response to the increasingly dedicated movement to stop the project.

In May of 2022, police once more raided the forest in hopes of clearing the woods of protesters. The operation marked a significant escalation in police activity in the woods, as agencies with the multi-jurisdictional task force entered with guns drawn, reportedly pointing their weapons at protesters as they worked to evict campers once more. Radio traffic from the day of the raid captured local police preemptively justifying the use of lethal force as they discussed what constituted a “deadly force encounter.”

Several months later, a two-day operation starting on Dec. 13, 2022, saw the multi-jurisdictional task force, armed with lethal and less-lethal weapons, close off a public park and enter the forest again. Once inside, they cornered tree sitters and confronted protesters occupying the forest. Police surrounded protesters in tree sits and peppered them with less-lethal weapons including tear gas and plastic bullets.

The raid ended early the next day with seven people arrested, six of whom were charged with state-level domestic terrorism offenses. It was the first time the charge was used against protesters in the fight against the project and marked a significant escalation in legal repression brought against activists in the movement.

As part of the justification for December’s domestic terrorism charges, Georgia law enforcement cited a U.S. Department of Homeland Security decision to classify the dispersed movement they say organizes under the name “Defend the Atlanta Forest” as a “Domestic Violent Extremist” group. Arresting officers referenced the designation in warrants presented to a judge during bail hearings, but it has since been reported that the DHS doesn’t use, or even have, any such classification.

Despite the non-existent “Domestic Violent Extremist” label, to date 19 people arrested in connection with protests against ‘Cop City’ are facing state-level domestic terrorism charges.

Those involved in the movement say the December arrests and charges sent a clear message — if you’re associated with the fight against ‘Cop City’ in any way, the state will use its full power to stop your activity. Further, activists on the ground who have warned of the potential for deadly force from police say that labeling protesters as “terrorists” has served to amplify police response and put law enforcement on edge as they confront forest defenders.

“We can see that, when you call a political movement terrorists, that functions as a dog whistle to the police, calling for more police violence,” Kautz, of the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, said.

Since the initial round of domestic terrorism charges in December, political leaders have consistently called protesters “terrorists” for things such as breaking windows, marching in the street, and being in the woods during the Jan. 18 raid. In the days following the Jan. 21 protest, Georgia Governor Brian Kemp declared a state of emergency while officials continued to describe property damage as violence.

“And so it’s no surprise that a police force who has been inundated with that kind of rhetoric will enter the forest during a raid as though it’s a military operation,” Kautz said. “They clearly believe that they’re entering a combat situation where they have to prepare to shoot and kill any threat.”

All of these factors culminated in the January 18 raid that left Tortuguita dead in the forest.

‘Raid, please help’

The morning of Jan. 18, the same multi-jurisdictional task force, including Georgia State Patrol SWAT teams, gathered outside Weelaunee before entering the woods to confront tree sitters and protesters. A forest defender who was in the woods on the morning of the raid recounted their experience with Unicorn Riot on the condition of anonymity.

“The first thing was, the person up in the tree heard crashing, and a banging,” the anonymous protester said.

The encampments included a number of tree sits — platforms built in tree tops that protesters occupy to prevent construction. The morning of the raid, several of these blockades throughout the woods housed activists. A thick fog obscured the tree sitter’s sight, but they would soon learn the sounds they heard were police with heavy machinery destroying a barricade protesters had built to block equipment from entering the area.

A yet-unknown number of police from across the region fanned out into the woods and started moving through the trees. Officers and troopers from different agencies closed in on protesters, who only learned of the raid after it had begun.

Police swept the forest, approaching tents and slashing any they came across after clearing occupants. Those in the tree sits were confronted by heavily armed police equipped to reach activists who had set up blockades in the forest’s canopy.

When police reached the wooded encampment that Terán had started for forest defenders who are queer, trans, Black, Indigenous and people of color, they came upon Tortuguita’s hammock, the spot where they slept, according to forest defenders who spoke with UR.

What happened next is unclear, and few concrete details have emerged since the killing, but the same anonymous protester on the ground described a text exchange that unfolded between Terán and others in the moments before their death.

“The last message we got from Tort was, ‘raid, please help.’,” the forest defender said. “And then as soon as people were texting, ‘what do you need,’ we heard one gunshot, then a bunch of gunshots.”

An independent autopsy completed January 31 would later reveal that Tortuguita was shot at least 13 times by multiple people.

One yet-to-be-identified GSP trooper was injured, reportedly with a bullet wound to their abdominal area, and evacuated to a nearby hospital.

Little detail about the moments between that text message being sent and Terán being shot to death has been released as of this article’s publication, but several versions of that morning’s events have since been put forth.

In the hours following the shooting, the GBI announced at a press conference that during the raid someone had, without warning, opened fire on a Georgia State Patrol trooper, after which GSP troopers fired back in defense. A written statement issued later the same day said that GSP troopers had encountered a person in a tent and given them verbal commands. The release says the person did not comply with police orders and shot the GSP trooper. The GBI would later claim that it recovered a 9mm Smith and Wesson handgun, reportedly registered to Terán, which was the weapon used to injure the GSP trooper.

But many in the movement are hard pressed to believe the state’s story. Organizers that UR spoke with suspect that the police, who were armed with military grade weapons and equipment and fed a steady diet of political rhetoric describing protesters as “violent” and “terrorists,” may have opened fire mistakenly, striking one of their own and prompting others to open fire on Terán.

While the Georgia Bureau of Investigation has said no bodycam footage of the shooting itself exists, bodycam videos released by the Atlanta Police Department on Feb. 8 capture audio of the shots that killed Terán and video of police activity in the area surrounding the site.

In the minutes after the shots rang out, Atlanta Police Department officers are heard commenting on the shots, saying it sounded like suppressed gunfire, like that which would come from a suppressed rifle used by the GSP’s SWAT teams.

“You fucked your own officer up,” one APD officer is heard speculating shortly after the shooting.

Immediately after the shooting, police evacuated the injured trooper to a nearby hospital. Radio traffic captured on the APD bodycam footage never included calls for medical support for Terán.

When police kill someone in Georgia, the incident is investigated by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI), an agency under the state’s Department of Public Safety (DPS). Georgia State Patrol, the police agency implicated in the killing, is also a division of the DPS, which has led community members to doubt the effectiveness of what the state is calling an independent investigation currently being done by the GBI.

The shifting story and lack of any corroboration, coupled with the conflict of interest in the state’s investigation, have left movement participants with little faith that the Georgia Department of Public Safety’s investigation will provide anything of value.

“The police, and Georgia State Patrol in particular, have every incentive to lie about what’s happened,” Kautz told Unicorn Riot while remarking on the need for an investigation without state conflicts of interest.

The Atlanta Solidarity Fund and other local organizations are calling for an independent investigation separate from the DPS and GBI, which activists say is the only hope for accountability or transparency after January’s killing.

The state has withheld information about the killing on the grounds that it’s part of an ongoing investigation, but Tortuguita’s family and community members are pushing for more transparency into the killing and the ongoing investigation.

‘Cop City will never be built’

From the first act of sabotage carried out against ‘Cop City,’ its opponents have been clear that they see no room for compromise in the overlapping struggles the fight represents. ‘Cop City’ and those fighting against it sit at the intersection of what activists describe as two critical struggles: the fight to defend ecologically valuable spaces in the face of climate change and the struggle against the carceral state that seeks to punish those fighting for a livable future.

“The stakes of Cop City and Ryan Millsap’s Hollywood dystopia being built here would be catastrophic, and if we think that the state repression tactics that they’re using right now are bad, I mean, get ready for when they can train on a mock city,” an anonymous forest defender told UR. “They’re ramping up for conflict. That’s why they want to build Cop City, is because they’re trying to get prepared for the next conflict where they’re going to have to beat people in the street again.”

The fallout from Tortuguita’s killing has rippled through Atlanta and well beyond. A wave of solidarity actions came in the days after their death, and a steady stream of reports documenting sabotage, property damage and protests targeting politicians and companies involved in building ‘Cop City’ has continued in the weeks since.

The actions, in Atlanta and beyond, speak to the movement’s commitment to its original no-compromise approach. Chants of “cop city will never be built” and “if you build it, we will burn it” are common at local protests against the project. The outpouring of actions following Tortuguita’s killing cement these words as promises more than sloganeering, but the escalation, activists say, has been solely fueled by the state’s violent response.

“They could call off the project, and everyone would go home,” the same anonymous forest defender said. “That’s their decision. We told them the terms, they just won’t accept them.”

But the movement includes more than militant saboteurs, and opposition has grown across political lines in the weeks since GSP killed Tortuguita.

On the day of the killing, Nicole Morado, a member of the Community Stakeholders Advisory Committee (CSAC), a governing body meant to serve as the public facing arm of the ‘Cop City’ project, resigned from the committee in protest. This was only made public days after it had happened, and Morado was later quoted as having said, “Really I did not want to be affiliated with a project that is using police violence and taking lives…,” as reported by SaportaReport.

On Feb. 6, another CSAC member appealed a land disturbance permit in a legal filing that could have delayed construction. Amy Taylor filed the appeal on the grounds that the land clearing would lead to increased runoff into Intrenchment Creek.

Students and faculty with the Atlanta University Center Consortium, a coalition of historically Black colleges and universities in the area, demanded that their institutions withdraw support for the project, while more than 1,300 social justice and civil rights groups from across the country called on Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens to resign over his handling of the situation. And groups ranging from physicians to faith leaders have weighed in, urging politicians to step in and stop the project.

But while those engaged in the fight to defend the Atlanta forest continue to organize and opposition to ‘Cop City’ grows, the city is barreling forward with the project, similarly refusing to compromise on its promise to build the police training compound.

On January 31, Mayor Andre Dickens, alongside DeKalb County CEO Michael Thurmond, announced their intention to move forward with the project while committing to “environmental protections and enhancements.” The same day, the city of Atlanta issued the final land disturbance permit required to begin construction on the police training campus. On Feb. 6, while the family of Terán addressed the public for the first time since their killing, heavily armed police once more raided the forest, escorting heavy machinery into the woods.

“I don’t know what it’s going to take to stop Cop City, but what I do know is that the APF could back out. The mayor could back out. City council could back out. They could stop at any time,” the forest defender said.

Until then, the activist said, those committed to stopping ‘Cop City’ will keep fighting, no matter the cost.

“Nobody wants their friends to get domestic terrorism charges, but people feel so strongly that they’re willing to risk that,” the forest defender said. “People feel like there is high enough stakes that it is worth that to do it.”

In March, the first mass gathering against ‘Cop City’ since the police killed Tortuguita will take place in Atlanta. Organizers hope that the “week of action” can bring together the growing opposition for the next phase of the struggle against ‘Cop City.’

Unicorn Riot's coverage on the movement to defend the Atlanta Forest:

- Landing Page: Unicorn Riot Coverage of the Movement to Protect the Atlanta Forest

- Federal and State Police Raid Three Homes in Atlanta Leading to One Arrest Amid ‘Cop City’ Investigation (February 8, 2024)

- One Year Since Tortuguita’s Killing: A Reflection on our Coverage of the Movement Against ‘Cop City’ and the First Eco-Activist Killed in the US (January 18, 2024)

- ‘Cop City’ Defendant Victor Puertas Has Been Held For Months Without Trial, but His Community Hasn’t Forgotten Him (November 26, 2023)

- No Charges For Georgia Troopers Who Killed Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Terán (October 6, 2023)

- Over 60 People Indicted on RICO Charges in Atlanta, Allegedly Promoting ‘Anarchist Ideas’ (September 5, 2023)

- Indigenous Climate Activist Victor Puertas Remains in Custody Despite No Indictment (July 26, 2023)

- 6th ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action – Unicorn Riot Coverage

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 8: Youth Rally; Atlanta Police Vehicles Torched (July 2, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 7: Cadence Bank ‘Drop The Loan’ Protest, Panel on Overpolicing (June 30, 2023)

- Clergy Demand Release of Indigenous Climate Activist Victor Puertas from ICE Detention (June 29, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 5: Cadence Bank Loan Protest, ‘March For the Forest’ (June 29, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 4: Rally to Reopen Intrenchment Creek Park (June 27, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 3: Bike Ride/Rally, Signature Gathering, Discussing Movement History (June 26, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Day 2: Rematriating Mvskoke Land; Hardcore Benefit Show (June 25, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Begins: Day 1 (June 24, 2023)

- ‘Their Overreach is Sowing the Seeds of Their Undoing’: Forest Defender Speaks from Bartow County Jail (June 20, 2023)

- ‘Cop City’ Protesters Visit Nationwide Insurance (June 14, 2023)

- Atlanta City Council Approves $67 Million in Public Funds for ‘Cop City’ (June 6, 2023)

- Atlanta Solidarity Fund Organizers Granted Bond (June 2, 2023)

- Three Atlanta Activists Arrested, Home Raided Over Bail Fund (May 31, 2023)

- ‘Don’t Forget Us’: Forest Defenders Confront Horrors of Life in DeKalb County Jail (May 30, 2023)

- ‘Cop City’ Panel Member Posted Slurs Online, Archived Tweets Indicate (May 18, 2023)

- ‘We Do Not Need a School for Assassins’: Hours of Public Comment Unanimously Against ‘Cop City’ (May 16, 2023)

- Three Face Felonies for Allegedly Flyering Near Home of One Georgia Trooper Tied to Killing of Forest Defender (May 8, 2023)

- One Granted Bond, Two Denied Pretrial Release: Forest Defenders Appear for Preliminary Hearings (May 4, 2023)

- No Gunpowder Residue Found on Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Terán According to DeKalb County Autopsy (April 21, 2023)

- Eight Remain in Jail from March 5 Weelaunee Forest Raid, 15 Released (March 24, 2023)

- Behind the #StopCopCity Domestic Terrorism Warrants (March 21, 2023)

- An Historic Direct Action in a Forest Outside Atlanta (March 18, 2023)

- Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Terán’s Independent Autopsy Report Released at Press Conference (March 13, 2023)

- Police Raid Atlanta Forest After ‘Cop City’ Opponents Overrun Security Post (March 5, 2023)

- ‘Stop Cop City’ Week of Action Begins in Atlanta (March 4, 2023)

- ‘Tortuguita Vive’: A No-Compromise Movement Responds to Police Killing a Forest Defender (February 27, 2023)

- Atlanta Activists Say Prosecutors Plan to Indict them on RICO Charges (February 25, 2023)

- ‘Community’ Committee Cheers Police Violence as Authorities Repress Resistance to ‘Cop City’ (February 24, 2023)

- Supporters of ‘Cop City’ Opponents Rally in Philly (February 24, 2023)

- Minneapolis March Connects Roof Depot Demolition Resistance to the Atlanta Forest (February 21, 2023)

- Atlanta PD Releases Bodycam Footage from Deadly Jan. 18 Forest Raid (February 8, 2023)

- Manuel ‘Tortuguita’ Terán’s Family Seeks Transparency in Police Killing (February 7, 2023)

- City of Atlanta and DeKalb County Announce ‘Agreement’ Amid Growing Opposition to Cop City (January 31, 2023)

- Marches and Vigils Across the US Respond to the Police Killing of Forest Defender Tort (January 22, 2023)

- Protester Shot and Killed by Officers During Raid on Atlanta Forest (January 18, 2023)

- Blackhall Intensifies Destruction of Weelaunee People’s Park in Atlanta Forest (January 16, 2023)

- SWAT Teams Attack Atlanta Forest Encampments, Activists Charged with ‘Terrorism’ (December 18, 2022)

- [Mini Doc] Defending the Atlanta Forest: Behind the Movement to Stop Cop City (Oct. 9, 2022)

- “Cop City” General Contractors’ Offices Attacked (May 19, 2022)

- Police Raid Atlanta Forest Occupation (May 18, 2022)

- Atlanta Fights to Save Its Forest (May 14, 2022)

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: