Denver’s ‘Right to Survive’ Ballot Initiative Voted Down

Denver, CO – The contentious ballot initiative 300, or Right to Survive, was voted down in Tuesday’s municipal elections with 81% of votes being against the ballot question. The initiative would have effectively repealed the Unauthorized Camping Ordinance (camping ban) passed in 2012, which criminalizes basic acts of survival such as eating, resting, and sleeping in public or private space with anything on top or underneath a person other than their clothing.

The passage of the initiative would have also nullified the Sitting or Lying Down in the Public Right-of-Way law (sit-lie ordinance) passed in 2005, which criminalizes sitting or lying down in the Downtown Denver Business Improvement District (BID) on the sidewalk or on a chair that is not “furnished by the city.”

While the language of the laws does not explicitly state they are intended for unhoused residents, Mayor Michael Hancock has spoken openly about supporting the camping ban ever since he first came into office (he won his third term as mayor on Tuesday, June 4 in a runoff vote) with the rhetoric that he is trying

“to figure out what to do about the growing presence of homeless people on Denver’s streets, and particularly in the downtown core areas, including the 16th Street Mall… We only have one downtown, we cannot afford to lose our city core.”

Advocates of initiative 300 recognize the camping ban and the sit-lie ordinance as directly targeting the unhoused population, and therefore created the initiative in order to restore the same basic human rights that housed people have to unhoused residents.

We spoke with Paul Boden, Western Regional Advocacy Project’s Executive Director, about the history behind the initiative and the laws it went up against:

“When we did the research behind it, we saw, I mean it jumped out: Sundown Town, Anti-okie laws, Japanese American Exclusion Act, Ugly laws. This country has an incredibly long history of passing local ordinances to criminalize activities that they know goddamn well everybody’s gonna break that law, everyone’s gonna stand still, everyone’s gonna sit down, everyone’s gonna sleep, everyone’s gonna eat. You make that a criminal offense, you have carte blanche to discriminatorily enforce those laws in order to rid communities of people that you don’t fucking want.”

Watch our interview with Boden below:

Throughout the months leading up to election day, there were wildly differing narratives about the initiative from both sides.

Denver Homeless Out Loud, the primary group behind the Denver Right to Survive Initiative Committee, submitted the initiative to the Denver Elections Division in April 2017. In December 2018, Roger Sherman, on behalf of Together Denver, filed their initial political committee statement with the elections division as the official opposition to the initiative.

A significant distinction between the two campaigns was their financing. Roger Sherman is the Managing Partner at public affairs company CRL Associates, which has represented Denver Metro Association of REALTORS (DMAR) for over 20 years. DMAR is the local board of the National Association of REALTORS (NAR) for Denver, and NAR tied with the Downtown Denver Partnership as the two top donors to Together Denver with donations of $200,000 each, which is more than double the total donations the Right to Survive campaign received.

The Downtown Denver Partnership largely created and lobbied for both the sit-lie and camping ordinances. In their 2011-2012 annual report, they touted that:

“the Partnership helped lead the successful lobbying efforts to institute a city-wide unauthorized camping ban to address behaviors negatively affecting businesses and the Downtown environment.”

This distinction of wealth contextualizes the basis for each side. The proponents using grassroots organizing and research from surveying hundreds of unhoused residents, and the opponents focusing on how the initiative could have potentially affected housed people, public spaces, and businesses.

From the written language of initiative 300 (see full text here), Together Denver had been, at the very least, misinforming the public that the initiative would allow people to exist in public space indefinitely. However the initiative did not mention once that it would supersede current curfews on public space, in fact it defined “public space” as “any outdoor property that is owned or leased, in whole or in part, by the City and County of Denver and is accessible to the public, or any city property upon which there is an easement for public use.” Therefore when a public park’s curfew is after sundown, it is no longer “accessible to the public.”

In an infographic produced by Together Denver and their partners entitled Denver Initiative 300: Impacts on the Homeless and Society by Granting Unimpeded Access to Public Space, they list Red Rocks Ampitheatre and the Denver Zoo as “areas impacted by initiative 300.” We reached out to the press contacts of each venue to check if they agreed with Together Denver’s rhetoric.

Brian Kitts, director of marketing and communications for Denver Arts and Venues (AVD), which includes Red Rocks Park and Ampitheatre, told us in an e-mail that Visit Denver’s stance “most directly reflect the business we’re in.”

Visit Denver’s name is listed on Together Denver’s endorsement page. The private, nonprofit trade association is contracted by the city & county of Denver to act as its official marketing agency. The city also released their own two-page memo in opposition to the initiative outlining the same propaganda as Together Denver.

The director of communications for the Denver Zoological Foundation, Jake Kubié, responded saying the zoo chooses not to comment on the initiative.

Another area of the initiative, which caused the opponents confusion, is section (d) (3):

“It shall be unlawful for an employee or agent of any government agency, corporation, business, or other entity to harass, terrorize, threaten, or intimidate any natural person exercising the rights secured by this ordinance.”

Together Denver, and the city and county of Denver, state that because the initiative did not define the word “harass,” then this section could limit the ability of outreach workers and others from offering services. However the state of Colorado currently has a law against harassment (C.R.S. 18-9-111), and therefore, defines what it means.

Terese Howard from Denver Homeless Out Loud (DHOL) spoke with us about Together Denver’s interpretation:

“This idea that the initiative will prevent outreach workers or service providers or others from approaching people who are homeless and offering services or offering help is a fear-mongering, absurd lie. It’s not true…

If somebody is simply offering services, asking if you need help, there is no comparison with that with harassment. There’s no legal grounds by which any of those cases would be found in court to be harassment.”

Together Denver states on their website that the initiative was “poorly written, overly-broad,” however the language of the initiative had been worked on for more than four years, and had even been put to vote by the Colorado legislature the past four legislative sessions in a row as the CO Homeless Bill of Rights (HBR). The bill’s organizational sponsor was advocacy group DHOL.

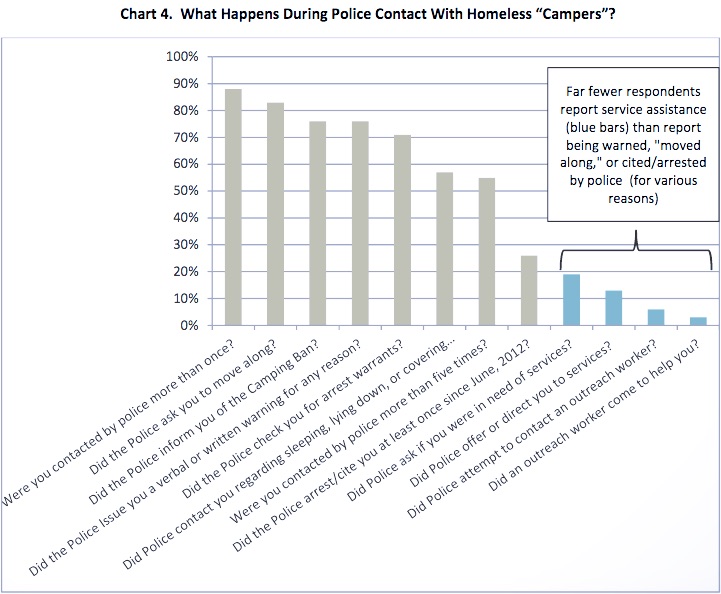

The Western Regional Advocacy Project, DHOL’s fiscal sponsor, constructed the original HBR from nearly 2,000 surveys of people living on the streets in California, so as to find out directly from the people experiencing houselessness what types of interactions they were having with police and private security, as well as their experiences in shelters, and surviving on the streets.

For the CO HBR, volunteers in DHOL, and in other advocacy groups in 12 cities across the state, surveyed more than 500 people living on the streets of CO in 2013 to focus on the local experiences.

In the past month there have been two report releases by two universities in Denver providing context and experiences directly from people living without housing. The first report was produced by the chair of the University of Colorado Denver Political Science Department, Dr. Tony Robinson, and a graduate student in Health and Behavioral Sciences, Marisa Westbrook, called Unhealthy By Design: Public Health Consequences of Denver’s Criminalization of Homeless.

The information in the 83-page report comes from surveys and interviews of 484 Denver residents experiencing houselessness. Some of the key findings include:

- “Constant contact with the police leads homeless people to achieve very little sleep, and only in short bursts: 70% of respondents report being woken often by police; 52% are constantly worried about police contact while they try to sleep. Those frequently woken by police typically sleep only in short bursts (~2 hours at a time) and achieve less than four hours of sleep per night, resulting in more negative health outcomes.”

- “‘Quality of life’ policing leads individuals to seek more hidden/isolated sleeping locations, undermining their safety: Our respondents all indicate increased rates of robbery, physical violence and sexual assault.”

- “This policing has led many homeless individuals to refrain from use of personal shelter, resulting in dangerous exposure to weather: Among those who have been instructed by police to quit using shelter from the elements, there is a higher rate of frostbite, dehydration, and heat stroke.”

- “Adequate housing/shelter options and personal hygiene facilities are not available on the scale needed for this community.”

The second report called In Support Of The Right To Survive, Denver Ballot Initiative 300 was produced by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law Homeless Advocacy Policy Project. This report mentions the Denver City Auditor’s 2015 report warning that the camping ban “may be worsening the City’s homeless situation by increasing the number of homeless people moving through the jail system.”

Enforcement of the camping ban is also highly expensive. A 2016 report by University of Denver Sturm College of Law called Too High a Price: What Criminalizing Homelessness Costs Colorado found that Denver spent at least $742,790 enforcing five anti-houseless ordinances in 2014.

Through open records requests, we found out (and reported) that Denver spent nearly $400,000 on contracting a private clean-up company to assist in clearing out camps of people without housing from September 2017 to September 2018.

For the amount of money the city spent on paying Custom Environmental Services for one year combined with the cost of enforcing the five anti-houseless ordinances in 2014, Denver could have built more than 130 tiny homes, at the average cost of $8,500 each, which could currently be housing 130-260 people.

A week before election day, a survival community called Jerr-E-ville named after village resident and DHOL volunteer, Jerry Burton, was among the hundreds of unhoused residents being swept nearly all day and night by police, public works, and Denver’s new contracted private clean-up company Environmental Hazmat Services. Terese Howard of DHOL said it was “the worst it’s ever been.”

Nearly a week before these intensified sweeps began, Burton had his last hearing stemming from a camping ban ticket he received in 2016. On April 29 at 1am, Burton received another camping ban ticket. Burton is a Marine Corps veteran who suffers from degenerative bone disease, which he says he got from his time stationed at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina.

The future of decriminalizing houselessness is unclear. However advocates are wondering what the “better” ideas Together Denver has, since their slogan was: we can do better.

“This shit is so fuckin’ simple if you think of the people that you’re talkin’ about as human beings, as oppose to ‘them'” – Paul Boden

UPDATE: We incorrectly reported that Michael Hancock won his third term as mayor during Tuesday’s municipal elections. He and other mayoral candidate Jamie Giellis will be voted on in a runoff vote on June 4. Our article now mentions that Hancock won during the runoff vote.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

Unicorn Riot coverage on Denver’s housing crisis and unhoused community:

- Crisis of the Unhoused – Landing Page for Unicorn Riot Coverage

- Dozens of Migrant Families Face Eviction in Aurora, CO with Less Than One Week’s Notice (Aug. 8, 2024)

- Denver Unhoused Advocacy Group Releases Winter Shelter Survey Data (May 8, 2024)

- Denver Migrant Encampment Faces Further Displacement, Auraria Campus Palestine Solidarity Camp Grows [Press Conference] (May 3, 2024)

- ‘Ya’ll Just Voted to Kill People!’: Denver City Council Upholds Mayor’s ‘No Freezing Sweeps’ Veto (February 23, 2024)

- Denver Passes ‘No Freezing Sweeps’ Bill, Potential Mayor Veto Looms (February 2, 2024)

- With Nearly 60 Frostbite Injuries in Unhoused Community, Advocates Encourage Denver to Do Better (December 21, 2022)

- Sit-in at Denver Recreation Center Leads to Meeting with City (March 23, 2022)

- Unhoused Community & Advocates Take Over Denver Recreation Center (March 10, 2022)

- Federal Judge Rules Denver Cannot Conduct Sweeps Without At Least 48-Hour Written Notice (Jan. 30, 2021)

- Denver Sweeps 300+ Tent Encampment Residents (Nov. 30, 2020)

- Seven Arrested at Action Against Houseless Sweeps (Nov. 20, 2020)

- Unhoused Residents Find Refuge at Downtown Vigil (Oct. 17, 2020)

- Denver Housing Advocates Launch 5256-Minute Vigil at City Hall (Oct. 14, 2020)

- Denver ‘Clean-ups’ Displace 100+ Unhoused Residents Amid Health Crisis (April 30, 2020)

- Housing First Advocates Protest USICH Director Marbut’s Visit to Denver (Feb. 21, 2020)

- Denver Police Cash In on Houseless Encampment Clean-Ups (Feb. 5, 2020)

- Judge Rules Denver’s Camping Ban Unconstitutional, Dismisses Jerry Burton’s Ban Ticket (Jan. 3, 2020)

- Advocates Demand Denver Protect Rights of People Without Homes (Oct. 21, 2019)

- Denver’s ‘Right to Survive’ Ballot Initiative Voted Down (May 9, 2019)

- “Unhealthy By Design:” CU Denver’s New Report About Camping Ban (April 13, 2019)

- Denver Paid Clean-Up Company $400,000 to Help in Houseless Sweeps (Nov. 27, 2018)

- Denver Police, City Workers Throw Away Belongings Amid Lawsuit (July 16, 2018)

- Class-Action Against Denver for Criminalizing Houselessness Moves Forward (May 11, 2018)

- Fourth Push for Homeless Bill of Rights in Colorado Legislature (March 14, 2018)

- First Lawsuit Hearing for Mobile Home Park Residents Suing Park Owners (March 2, 2018)

- Denver’s First Tiny Home Village ‘Beloved Community Village’ Turns Six Months Old (January 19, 2018)

- Denver Park Rangers Take Sleeping Bag, Tent from Houseless Man in 25 Degree Weather (November 12, 2017)

- Eighty Families Offer to Purchase Mobile Home Park to Avoid Eviction (September 25, 2017)

- Denver Human Rights Activist and Community Organizer, Terese Howard, Faces Up to 30 Days in Jail (August 24, 2017)

- Class-Action Lawsuit Against Denver: Motions Filed for Summary Judgement (August 15, 2017)

- U.S. District Court of CO Certifies One of the Largest Houseless Class-Actions in U.S. History (April 29, 2017)

- Three Convicted in Camping Ban Trial Two Weeks Ahead of Right to Rest Act Hearing (April 18, 2017)

- Three Co-Defendants Fight Denver’s Camping Ban in Court (April 4, 2017)

- Third Push for Homeless Bill of Rights in Colorado Legislature (Feb. 24, 2017)

- With Mayor’s Approval, Denver Continues Survival Gear Confiscations (Dec. 16, 2016)

- Denver to Continue Confiscating Survival Gear of Unhoused Under Encumbrance Ordinance, to Stop Under Camping Ban (Dec. 11, 2016)

- Denver Intensifies Sweeps of Unhoused Community and Confiscates Survival Gear; Parade of Rights Rally (Dec. 4, 2016)

- First Hearing in Class-Action Against Denver for Violating Human Rights (Oct. 14, 2016)

- Class-Action Lawsuit Against Denver: Motion Filed for Recusal of Judge Shaffer (Sept. 22, 2016)

- People Without Housing File Lawsuit Against the City of Denver (Aug. 27, 2016)

- Denver’s Affordable Housing Displaces Low-Income Residents (June 20, 2016)

- City of Denver Cracks Down on its Homeless Community (Dec. 20, 2015)

- Homeless Forced Out of Tents and into Snowstorm by Denver Police (Dec. 16, 2015)

- Resurrection Village: Denver Police Destroy Tiny Homes and Arrest Builders (Oct. 27, 2015)