Denver Police Cash In on Houseless Encampment Clean-Ups

Denver, CO – For nearly eight years Denver police officers, public works employees, park rangers, and occasionally inmates have been carrying out and enforcing the Unauthorized Camping Ordinance (camping ban) signed into law by Mayor Michael Hancock during his first term in 2012. When investigating how much Denver spends on the ‘sweeps,’ the break-down and clean-up of unhoused peoples’ outdoor communities, Unicorn Riot uncovered that from September 2017 to July 2019, the city paid private clean-up companies approximately $713,692.

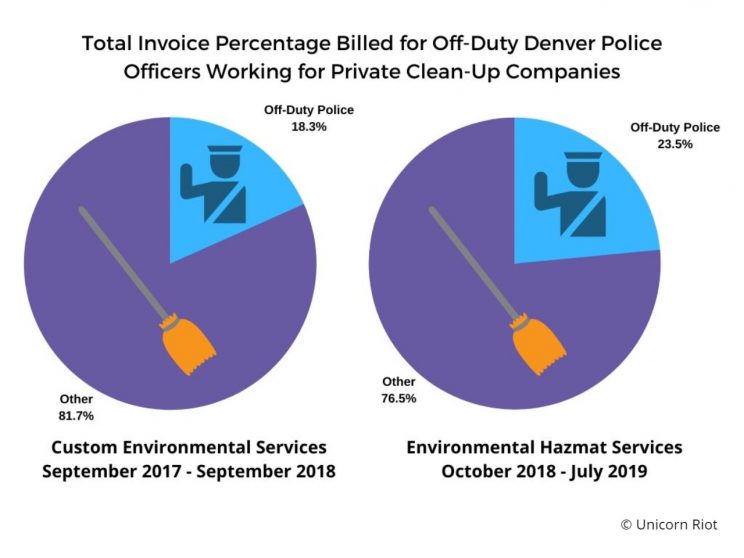

Over 20% of that total went to off-duty Denver police officers contracted by the clean-up companies.

At least four years into the camping ban’s passage, Denver began contracting private clean-up companies to assist public works (now the Department of Transportation & Infrastructure) in the sweeps. In November 2018, Unicorn Riot published an exclusive story highlighting invoices (PDF) we obtained through the Colorado Open Records Act (CORA) of contracted clean-up work between Custom Environmental Services, Inc. (CES) and the city of Denver.

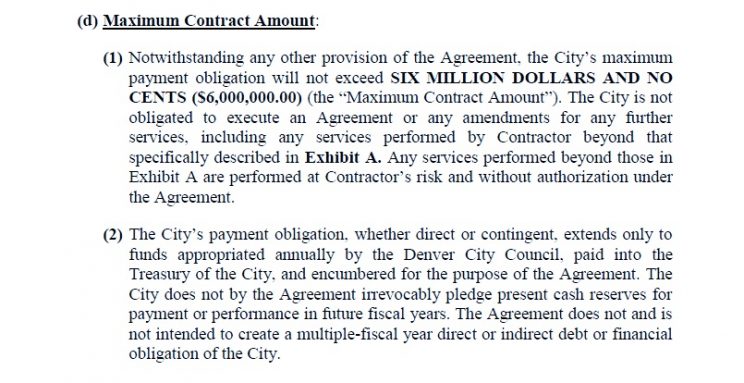

From September 2017 up until September 2018, Denver paid CES nearly $400,000. We recently obtained invoices (PDF) and e-mails (PDF) between the city and their new contracted clean-up company Environmental Hazmat Services (EHS). In the contract signed on October 11, 2018, the maximum contract amount up until October 11, 2021 is $6 million.

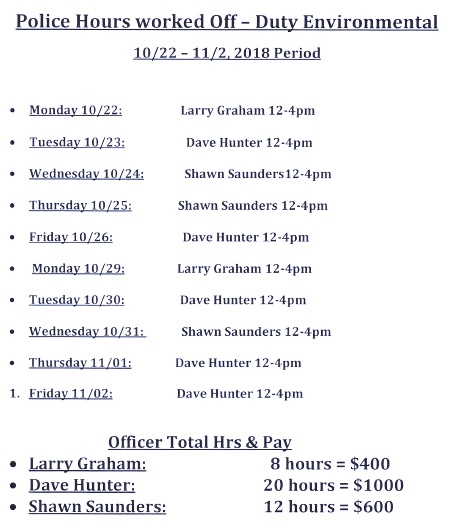

In order to effectively execute the camping ban, Custom Environmental Services (CES) billed for a “Security Officer” each day within every weekly invoice (PDF) from September 2017-2018. The security personnel received $75/hour for a standard shift of 4 hours. At the end of each invoice, Sergeant Tony Martinez also received $75/hour for 4 hours of “Admin/Scheduling” work.

The Environmental Hazmat Services (EHS) invoices (PDF) contain the same line items, though they specify that the people filling the security role, which they term “Security Guard” in their invoices, are off-duty Denver police officers. While working for EHS, off-duty police received $68/hour.

Before Denver’s camping ban was passed, in October 2011 Mayor Hancock, who had been sworn into office three months prior, spoke openly about supporting such a ban:

“We only have one downtown, we cannot afford to lose our city core. If people don’t feel safe going downtown, that is a threat to the very vitality of our downtown and our city. I was surprised as anyone to learn that you can sleep on the [16th Street] mall. Why is that the case?” — Mayor Hancock

At the same time, the recession which exploded in 2008 was still plaguing the country. Three years later, the number of people living in poverty and on the streets had increased due to the millions of foreclosures and bankruptcies largely caused by over three decades of federal divestment from affordable housing infrastructure and programs (PDF), and a severe lack in oversight and accountability.

In response was the Occupy Wall Street movement sprouting in New York City on September 17, 2011, inspired by previous massive public protests in Cairo, Madrid, and Athens. The movement spread seeds of resistance all over the world, including in Denver where, at its pinnacle, the Occupy Denver encampment had 70 tents. Meanwhile thousands of unhoused residents with no connection to the social movement continued surviving on the streets.

Instead of listening to the demands of the people in the movement, who were calling for affordable housing and true steps towards remediating the mass suffering caused by the recession, the city passed the camping ban.

The ban effectively criminalizes basic acts of survival such as eating, resting, and sleeping in public or private space with anything on top or underneath a person other than their clothing.

The camping ban was largely lobbied for and supported by the Downtown Denver Partnership (DDP), a lobbying and investment firm for private sector businesses, “to address behaviors negatively affecting businesses and the Downtown environment,” according to DDP’s 2011-2012 Annual Report (PDF).

Tami Door, president and chief executive of the DDP, further explained how poverty is bad for business to the Denver Post in 2011:

“There’s no question that we have serious concerns over the increased numbers of individuals on the streets. There are behaviors that aren’t acceptable and we need to explore ways in which we address these.” — Tami Door

Through the enforcement of the camping ban, unhoused residents are regularly contacted by police officers, whether it’s by being woken up in the middle of the night and being ordered to move, or during the day for eating or resting in a public space.

Members of the local unhoused community and their advocates have been trying to get the camping ban (or as they call it, the “survival ban”) overturned since its passage, and right before the new year they came as close as they’ve ever been. In the conclusion of a motion-to-dismiss hearing for a camping ban citation, Denver District Judge Johnny C. Barajas ruled the city’s camping ban unconstitutional, coinciding the ticket’s dismissal.

Though the sweeps or ‘clean-ups’ largely slowed down after the ruling on December 27, 2019, the city reverted back to business-as-usual only ten days later. Now, instead of citing the camping ban as their lawful justification, they cited the ‘encumbrance removal’ ordinance (DRMC Section 49-246) (PDF).

This enforcement tactic is not new, in fact, the city did the exact same thing in December 2016. That winter, the Denver police came under fire for being live-streamed taking blankets away from people sleeping outside. Mayor Hancock responded by ordering a temporary end to the confiscation of survival gear including tents and blankets during the winter months. However, the careful clarification in his statement kept the door open for continued confiscations under the encumbrance removal ordinance.

Denver uses many different laws to criminalize unhoused residents and to justify move-on orders. According to Too High a Price 2: Move on to Where?, a 2018 report by University of Denver Sturm College of Law:

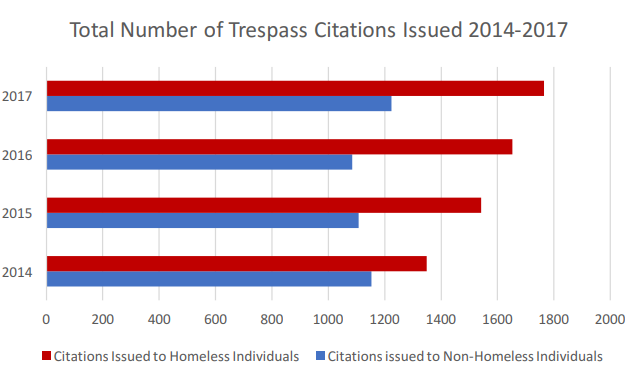

“Denver police cited homeless individuals for 53.9% of all Trespass citations given in 2014—a percentage that has risen to 59% in 2017 and was as high as 60.3% in 2016. Citations under the Curfews and Closures ordinance are similarly telling. In 2014, homeless individuals received 60.2% of all citations under the Section 39.3 ordinance. This percentage grew to 76.5% in 2017.” — Too High a Price 2 Report

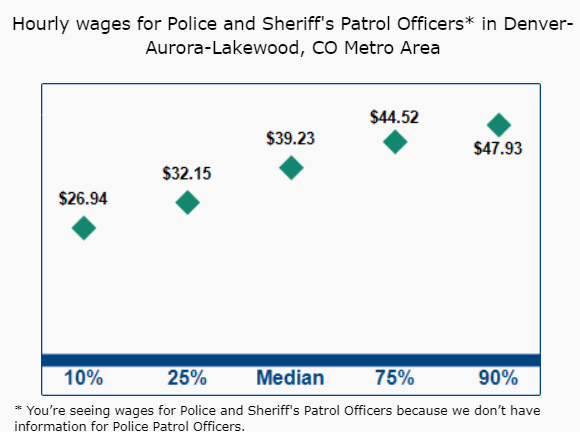

The payout for police officers may be one of the reasons for maintaining the sweeps, no matter the legal justification. The hourly wage from Environmental Hazmat Services (EHS) for off-duty Denver police officers is more than the officers’ hourly wage while working for the city.

While contracted through EHS at $68/hour, off-duty police made more than time-and-a-half in relation to their city hourly wage.

The average median hourly wage for police and sheriff’s patrol officers in Denver, Aurora and Broomfield, CO is $39.23.

From the approximately nine months of bi-monthly EHS invoices we received (from October 22, 2018–July 26, 2019), off-duty Denver police officers working as security during the clean-ups received an average mean of $2,760.8 from each invoice; 20.16% of the average mean of the total amount of each of the invoices.

There are six invoices specifying work from the storage unit at 1496 Galapago Street, the temporary storage location for people’s property obtained during the clean-ups. In these invoices, off-duty Denver police officers received an average mean of $3,082.66 from each invoice; 46.41% of the average mean of the total amount of each of the invoices.

The total amount off-duty Denver police officers received for working as security for EHS from October 2018 to July 2019 was $73,712, which is 23.49% of the sum of all of the invoices. The total amount EHS invoiced the city of Denver for during that timeframe was $313,692.

Including the nearly $400,000 from the city’s contract with CES, the city paid clean-up companies almost $714,000 from September 2017 to July 2019.

Even though the CES invoices from September 2017–2018 do not specify who was filling the role as “Security Officer” it is undoubtedly Denver police officers since Sergeant Tony Martinez was paid in each of the invoices for scheduling.

In the Denver Police Department Operations Manual (PDF) under Section 114.01: Secondary Employment (3)(l) it states that officers are only permitted to work secondary jobs that are scheduled by someone in the police department. Therefore, from those 11 months of invoices, off-duty Denver police officers received $71,400, which is 18.33% of the total amount of all of the invoices.

Off-duty Denver police officers profited a total of $145,112 from the clean-up company contracts with CES and EHS from September 2017 to July 2019.

Because these payment sums only involve the off-duty work of Denver police officers contracted through private clean-up companies, the amount gained by the other officers present during the sweeps is unclear. Although the CES and EHS invoices only bill for one or two off-duty police officers per day, during the sweeps there are always more than two officers present, according to consistent observations from people who have been swept, from organizations such as Denver Homeless Out Loud, and from Unicorn Riot’s own investigations.

The other police officers present are most likely on-duty, meaning they are working their official assigned duty during their required duty times, yet some may be working overtime.

All the Denver police officers present at sweeps, whether on-duty or present in an off-duty capacity, have been seen in uniform. In fact, many secondary employment/detail positions allow for off-duty officers (PDF) to wear their uniforms, including the non-lethal and lethal gear that come with it.

Unicorn Riot reached out to the Denver Police Department for comment on their off-duty police officers working for private clean-up companies, however they did not respond.

We also reached out to Andy McNulty, an attorney with Killmer, Lane & Newman, LLP, who represented Jerry Burton in the motion-to-dismiss hearing when the camping ban was found unconstitutional, who gave us a statement:

“The fact that Denver is paying these police officers a king’s ransom to essentially sweep our homeless residents out-of-sight is a travesty.” — Andy McNulty

Below are the e-mails we received through Colorado Open Records Act requests between Environmental Hazmat Services, Denver Public Works, Denver Department of Public Health and Environment, and the Denver Police Department. You can also click here for the PDFs.

EHS E-Mails and Contract

Below are the invoices we received through Colorado Open Records Act requests billed to the city and county of Denver from Environmental Hazmat Services. You can also click here for the PDFs.

EHS Invoices

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

Unicorn Riot coverage on Denver’s housing crisis and unhoused community:

- Crisis of the Unhoused – Landing Page for Unicorn Riot Coverage

- Dozens of Migrant Families Face Eviction in Aurora, CO with Less Than One Week’s Notice (Aug. 8, 2024)

- Denver Unhoused Advocacy Group Releases Winter Shelter Survey Data (May 8, 2024)

- Denver Migrant Encampment Faces Further Displacement, Auraria Campus Palestine Solidarity Camp Grows [Press Conference] (May 3, 2024)

- ‘Ya’ll Just Voted to Kill People!’: Denver City Council Upholds Mayor’s ‘No Freezing Sweeps’ Veto (February 23, 2024)

- Denver Passes ‘No Freezing Sweeps’ Bill, Potential Mayor Veto Looms (February 2, 2024)

- With Nearly 60 Frostbite Injuries in Unhoused Community, Advocates Encourage Denver to Do Better (December 21, 2022)

- Sit-in at Denver Recreation Center Leads to Meeting with City (March 23, 2022)

- Unhoused Community & Advocates Take Over Denver Recreation Center (March 10, 2022)

- Federal Judge Rules Denver Cannot Conduct Sweeps Without At Least 48-Hour Written Notice (Jan. 30, 2021)

- Denver Sweeps 300+ Tent Encampment Residents (Nov. 30, 2020)

- Seven Arrested at Action Against Houseless Sweeps (Nov. 20, 2020)

- Unhoused Residents Find Refuge at Downtown Vigil (Oct. 17, 2020)

- Denver Housing Advocates Launch 5256-Minute Vigil at City Hall (Oct. 14, 2020)

- Denver ‘Clean-ups’ Displace 100+ Unhoused Residents Amid Health Crisis (April 30, 2020)

- Housing First Advocates Protest USICH Director Marbut’s Visit to Denver (Feb. 21, 2020)

- Denver Police Cash In on Houseless Encampment Clean-Ups (Feb. 5, 2020)

- Judge Rules Denver’s Camping Ban Unconstitutional, Dismisses Jerry Burton’s Ban Ticket (Jan. 3, 2020)

- Advocates Demand Denver Protect Rights of People Without Homes (Oct. 21, 2019)

- Denver’s ‘Right to Survive’ Ballot Initiative Voted Down (May 9, 2019)

- “Unhealthy By Design:” CU Denver’s New Report About Camping Ban (April 13, 2019)

- Denver Paid Clean-Up Company $400,000 to Help in Houseless Sweeps (Nov. 27, 2018)

- Denver Police, City Workers Throw Away Belongings Amid Lawsuit (July 16, 2018)

- Class-Action Against Denver for Criminalizing Houselessness Moves Forward (May 11, 2018)

- Fourth Push for Homeless Bill of Rights in Colorado Legislature (March 14, 2018)

- First Lawsuit Hearing for Mobile Home Park Residents Suing Park Owners (March 2, 2018)

- Denver’s First Tiny Home Village ‘Beloved Community Village’ Turns Six Months Old (January 19, 2018)

- Denver Park Rangers Take Sleeping Bag, Tent from Houseless Man in 25 Degree Weather (November 12, 2017)

- Eighty Families Offer to Purchase Mobile Home Park to Avoid Eviction (September 25, 2017)

- Denver Human Rights Activist and Community Organizer, Terese Howard, Faces Up to 30 Days in Jail (August 24, 2017)

- Class-Action Lawsuit Against Denver: Motions Filed for Summary Judgement (August 15, 2017)

- U.S. District Court of CO Certifies One of the Largest Houseless Class-Actions in U.S. History (April 29, 2017)

- Three Convicted in Camping Ban Trial Two Weeks Ahead of Right to Rest Act Hearing (April 18, 2017)

- Three Co-Defendants Fight Denver’s Camping Ban in Court (April 4, 2017)

- Third Push for Homeless Bill of Rights in Colorado Legislature (Feb. 24, 2017)

- With Mayor’s Approval, Denver Continues Survival Gear Confiscations (Dec. 16, 2016)

- Denver to Continue Confiscating Survival Gear of Unhoused Under Encumbrance Ordinance, to Stop Under Camping Ban (Dec. 11, 2016)

- Denver Intensifies Sweeps of Unhoused Community and Confiscates Survival Gear; Parade of Rights Rally (Dec. 4, 2016)

- First Hearing in Class-Action Against Denver for Violating Human Rights (Oct. 14, 2016)

- Class-Action Lawsuit Against Denver: Motion Filed for Recusal of Judge Shaffer (Sept. 22, 2016)

- People Without Housing File Lawsuit Against the City of Denver (Aug. 27, 2016)

- Denver’s Affordable Housing Displaces Low-Income Residents (June 20, 2016)

- City of Denver Cracks Down on its Homeless Community (Dec. 20, 2015)

- Homeless Forced Out of Tents and into Snowstorm by Denver Police (Dec. 16, 2015)

- Resurrection Village: Denver Police Destroy Tiny Homes and Arrest Builders (Oct. 27, 2015)