Commemoration for Sandy Lake Tragedy Seeks Healing

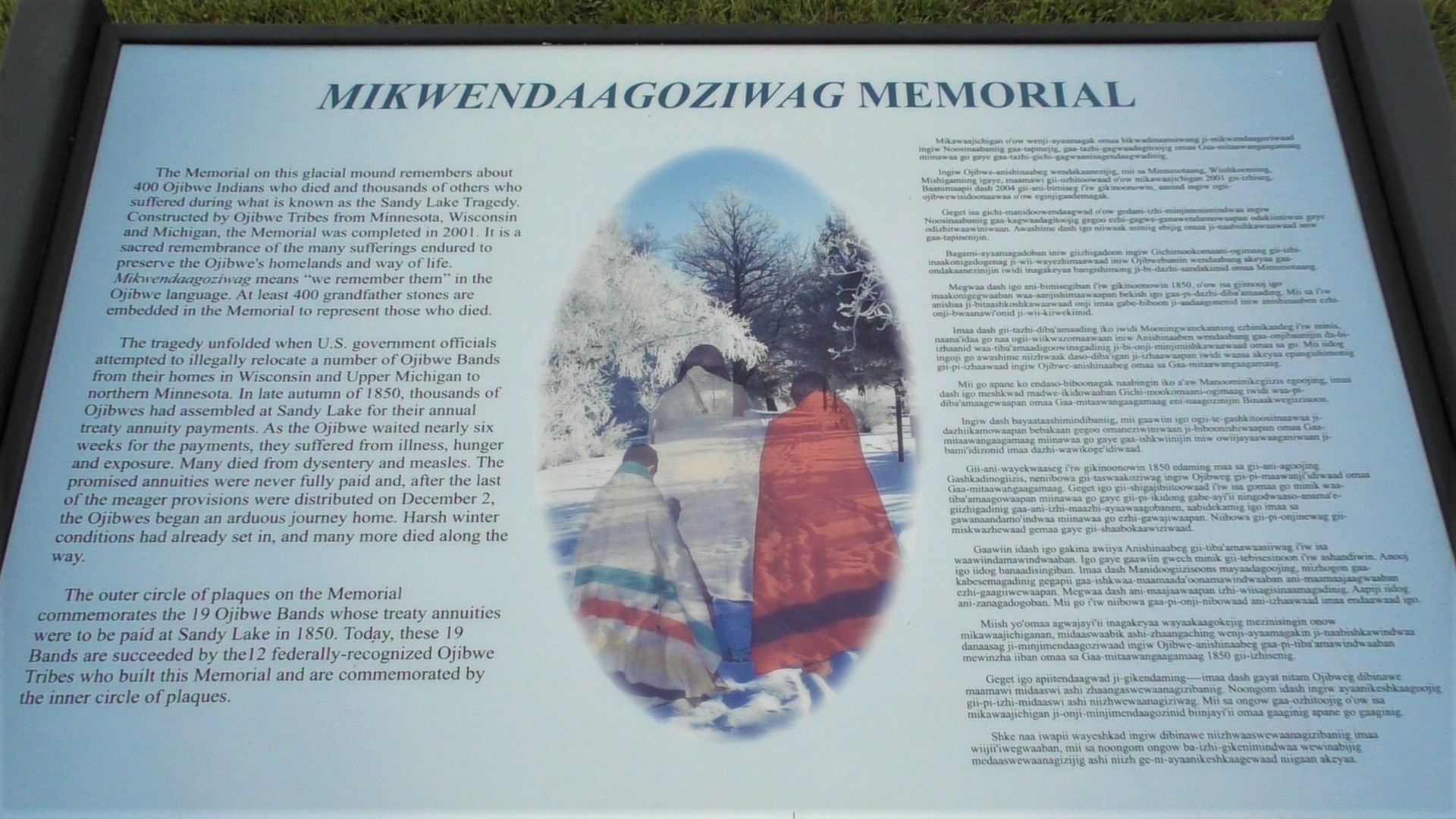

Big Sandy Lake, MN – Descendants, relatives, and people from all walks of life have come to Big Sandy Lake, Minnesota for the last two decades to commemorate the catastrophic Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850, in which over 400 indigenous Anishinaabeg people died from U.S. Government actions. Unicorn Riot visited the Mikwendaagoziwag ‘We Remember Them’ Ceremonies commemoration in July 2018 to learn more about the tragedy and its impacts on Minnesota and beyond.

Commemoration for Sandy Lake Tragedy Seeks Healing from Unicorn Riot.

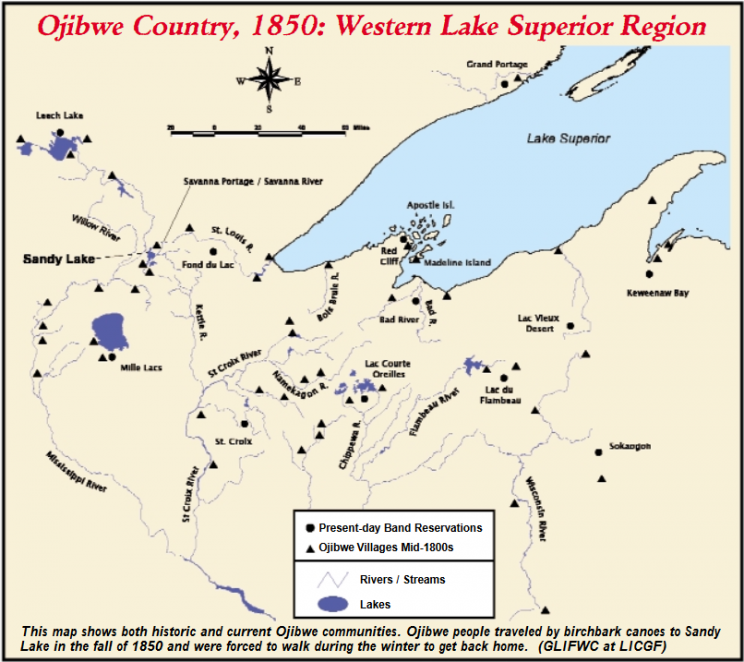

The commemoration spoke about the United States’ efforts to get American Indian tribes moving west out of Wisconsin past the Mississippi River. After Anishinaabeg people refused to move, the U.S. government relocated the annuity/treaty payment site from Madeline Island, Wisconsin, the spiritual capital of the Ojibwe, to Sandy Lake, Minnesota. When over 5,000 Anishinaabeg came to Sandy Lake in the fall of 1850 for their payments, they were met with no money or goods, and given limited food that was contaminated. Hundreds got sick and died while waiting for payments which never came, and with rivers frozen over in the thick of winter, hundreds more died on the journey back home.

The annuity/treaty payments were compensation for lands ceded in the 1837 Treaty with the Chippewa, in which the the United States received most of Upper Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota. Sandra Skinaway, Tribal Chairwoman of the Sandy Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa explained at the opening of the commemoration that events like this tragedy are part of their people’s historical trauma:

“What happened in 1850 … is part of our trauma, historical trauma … Some of us are still dealing with this historical trauma. And ceremonies like this, to remember those who were lost, who were sacrificed, and who have sacrificed, is helping with some of that healing process.” – Sandra Skinaway, Tribal Chairwoman of the Sandy Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

The commemoration was organized by the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), a tri-state organization representing eleven Ojibwe tribes “who reserved hunting, fishing and gathering rights in the 1837, 1842, and 1854 Treaties with the United States government.”

The first commemoration started at Madeline Island 150 years after the tragedy. Descendants and community gathered at the island, participated in ceremony and prayers, and then carried a massive memorial rock with them as they traveled by canoe and foot on roughly the same path taken in 1850, to the place it stands now, off the shore of Big Sandy Lake.

The exact path in which many of their ancestors traveled in 1850 to get to Sandy Lake could not be taken as dams, roads, and logging have forever altered the landscape of northern Minnesota.

Mounted on the memorial rock are placards with names of bands of tribes impacted by the tragedy. We heard from several of the attendees at the event that a handful of the tribes represented on the rock are now extinct.

Jim Merhar of the White Earth Reservation told us he had known about the history of the Sandy Lake Tragedy for some time and that he initially heard about the ceremony on the radio. After the first year, the annual commemoration has since been held at Big Sandy Lake, Minnesota. “When they built the memorial,” he said, “it was awesome.”

Every year, the commemoration begins in ceremony at the east end of Big Sandy Lake and then people canoe to the memorial side of the lake where a water ceremony is held. Further ceremonies and speeches occur after the yearly feast. This year, the feast featured fried white fish and walleye, salad, watermelons, and an assortment of other foods.

We spoke to some of the volunteers making food, Sirella from Lac Courte Oreilles spoke to us as she helped cook fry-bread for hundreds and said that she was in Madeline Island for the first commemoration and that she felt it was very important to remember her ancestors “in a good way and [do] things for ourselves in a good way for our future generations.”

Mic Isham, Executive Adminstrator at GLIFWC and Chairman of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, hosted the commemoration and said the event was “a big responsibility” because “they do not teach this in the schools.” Furthermore, Brad Harrington, Commissioner of Natural Resources of the Mille Lacs Band, said,

“It’s events like these that open my eyes to a larger history that my people, that our people, hold. Something that I was taught to forget through an American education system. I am very grateful to the people that put this on.“

The Chair of GLIFWC, Jim Williams, expressed his joy in seeing so many people there: “I know our ancestors upstairs are dancing because they are happy to see everyone here.” Mike Wiggins, Tribal Chairman of the Bad River Band said he was “humbled” to be a part of the commemoration and that sending “love, gratitude, and remembrance back is really a powerful, beautiful thing.”

Speakers during the ceremony frequently mentioned they are survivors of the ongoing genocide on indigenous peoples, and they are still here, still living. Jason Schlender, the Vice Chair of Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, stated:

“I’ve been a part of this ceremony for a long time, and fortunate enough to be home schooled on what happened many years ago. So I stand here before all of you and with all of us together to celebrate that we’re survivors. Our people have endured unimaginable tragedy and genocide and still here we are today. We still have our language and culture and our way of life and our music.“

We also learned more about the tragedy from Keenan Gonzales of the Mississippi Band of Ojibwe from East Lake, Minnesota. He told us how during the tragic winter of 1850-1851, the locals brought “stockpiled rice and deer meat” for those that had traveled long distances and “were waiting for their annuity payments that were BS.”

Gonzales said the “massacre really started to take hold when we were walking home in the middle of winter.” He said there wasn’t enough food or water to walk home, so many people “collapsed dead.” Because the ground was frozen, they couldn’t bury the dead, so they left them “a little bit of tobacco and a little bit of food for their journey to the spirit world.”

The Objibwe were “water people“, Gonzales said, using the water to travel, and during the tragedy in 1850, the water had frozen over in the winter so people had to burn their birch bark canoes for warmth.

“We were river people, water people. So our highways were the rivers and lakes that crisscrossed.” – Keenan Gonzales

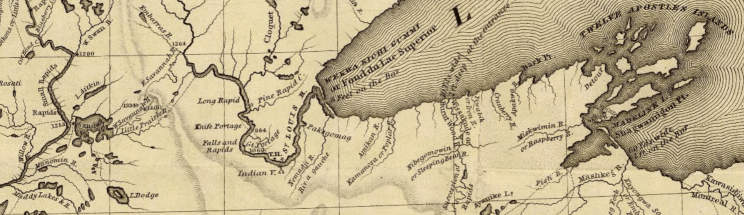

We learned more history from Jim Mehrar, who sat with Red Cliff tribal member and Deputy Administrator at GLIFWC, Gerald DePerry, about how their ancestors traveled using the waterways. The waterways used to be “quite a highway system” said Mehrar, who said he looked at old surveyor maps from Leech Lakes of all the trails. Mehrar described how people would go north to hunt and fish and how they would canoe different waterways and portage to the next river.

They spoke about how the landscape has been forever altered from 175 years ago, as loggers slaughtered most of the white pine trees and the United States Army Corps of Engineers constructed numerous dams along the Mississippi River, destroying many sacred sites and altering the paths of waterways.

“Loggers came in here and logged it all off, slaughtered it. We got just a few white pines left.” – Jim Merhar

Minnesota’s history of European settlement is still recent, as the Sandy Lake Tragedy occurred before Minnesota was even a state. Settler expansion into the Minnesota territories was led by military emplacements like Fort Snelling which was completed at the confluence of the Minnesota and the Mississippi Rivers in the 1820s. Military posts, like Fort Snelling, operated to protect fur traders, white settlements, and further colonial expansion. Fort Snelling was later used as a concentration camp in the 1860s for thousands of Dakota people, hundreds of whom would die there.

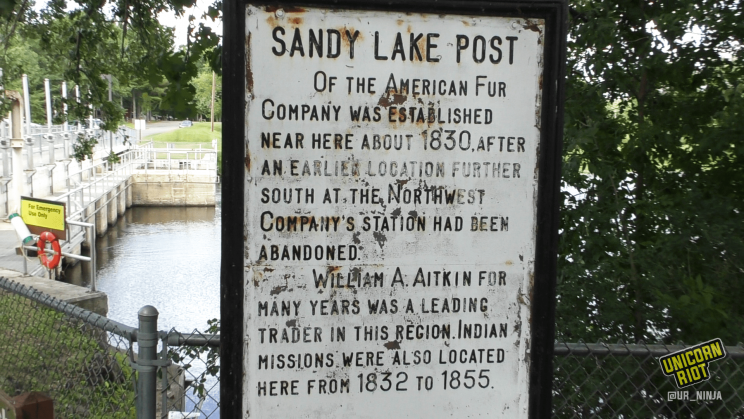

As European settlers and traders ventured deeper into the Minnesota territory, they created trading posts and what they called Indian mission stations geared to Christianize the local Indian population. The Sandy Lake Post was established around 1830, and seventy miles east at Crow Wing was the northernmost white settlement and a major trading post by 1837.

After the Treaty of 1837, white settlement surged as land became widely available in the Minnesota region, depleting resources for others as hunger and disease struck many Anishinaabeg in northern Minnesota.

Between 1850 and 1860 the area saw a massive settler population explosion. The 1850 census recorded 6,077 European-Americans and an estimated 12,000 Native Americans residing in the Minnesota Territory. By 1860, two years after Minnesota became an official US state, the population had boomed to 172,000 European-Americans living in Minnesota, with just 2,639 recorded Native Americans left.

The first governor of the Minnesota Territory was Alexander Ramsey, who had a well known deep-seated hatred for Native Americans, as governmental policies were enacted to force Native Americans to move west of the Mississippi, Ramsey called for the extermination of Native Americans. He ordered mass executions, several massacres of people and buffalo, put bounties out, and made concentration camps for Indians in Minnesota, Ramsey is quoted as saying:

“The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state.” – Minnesota Territory/State Governor Alexander Ramsey

The legacy of events like the Sandy Lake Tragedy can be seen in schools, cities, and counties across Minnesota that are named after the genocidal Governor who oversaw the relocation attempts. At least one school in Minneapolis has been renamed so as to not honor Ramsey’s genocidal legacy.

Historian and American Indian Studies Professor Brenda Child also spoke at the commemoration and gave further context to the tragedy that unfolded in 1850. Child said she found memoirs about the 1850 trip from Madeline Island to Sandy Lake, written by Julia Warren Spears, sister of translator and historian William Warren, in the archives at the Historical Society.

Child told those gathered at the memorial that the real number of those that perished during the tragedy is much higher than is accounted for, as other stories, like those of the tribes that came north up the Mississippi to Sandy Lake and had died on their way home, are often overlooked.

After Professor Child spoke, Mic Isham, the host of the day, thanked everybody for coming. The commemoration closed with a round dance and traveling song. Isham spoke with Unicorn Riot after the commemoration and said, “It’s a sad thing, but remembering and doing the event makes you feel good. It’s like a completion, or closure. It just helps. When you think about it and it’s sad, doing the ceremony helps you get over that sadness.”

Watch our livestream coverage of the Commemoration of the Sandy Lake Tragedy with interviews in the first portion and speeches from the commemoration in the second.

In the year 2000, GLIFWC created a two-page brochure on the Sandy Lake Tragedy and Memorial. Successor annuity bands of those who perished helped create the memorial: Fon du Lac Band, Grand Portage Band, Leech Lake Band, Mille Lacs Band, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, Lac Vieux Desert Band, Bad River Band, Lac Courte Oreilles Band, Lac du Flambeau Band, Red Cliff Band, St. Croix Band, and the Sokaogon Band.

SandyLake_BrochureBad River Band tribal Chairman Mike Wiggins, after displaying his gratitude and joy with the commemoration, he said,

“When I think about what took place and the sacrifices that they made, 450 of our people losing their lives … that was just a couple blinks of an eye ago and it feels really real, it feels like it could still be happening today and when I think of the land and the water, in a way it is.” – Mike Wiggins, Tribal Chairman of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians

A month before the commemoration, Minnesota’s Public Utilities Commission gave the green light to Enbridge to construct the Line 3 replacement pipeline. We first learned about the tragedy as we followed #Stopline3 protests in northern Minnesota.

To learn more about the Line 3 pipeline, the impacts of the project, and how people are resisting it, check out Unicorn Riot’s preivous Line 3 reporting:

Unicorn Riot's Line 3 Oil Pipeline Coverage:

- Landing Page for all Unicorn Riot Line 3 Resistance Coverage

- Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison Speech Disrupted by Water Protectors - October 8, 2021

- Over 50 Line 3 Pipeline Protesters Arrested Outside MN Governor’s Residence - September 22, 2021

- Police Break Up Ceremony and Indigenous-Led #StopLine3 Occupation - August 31, 2021

- Hundreds March from Governor Residence, Urge Chase Bank Defund Line 3 - August 31, 2021

- First Trial from Treaty People Gathering Ends in Acquittal - August 23, 2021

- Line 3 Opponent Sentenced to Thirty Days in Jail - August 19, 2021

- Enbridge Spills 10,000 Gallons of Line 3 Drilling Fluid - August 16, 2021

- Line 3 Fusion Center Data Declared Secret - August 4, 2021

- Judge Orders Sheriff to Halt Harassment of Line 3 Resistance Camp - July 24, 2021

- Water Protectors Occupy Work Sites and Lock Down to Line 3 Pipeline Construction - July 1, 2021

- Hubbard County Barricades Private Property, Imprisons Water Protectors - June 28, 2021

- Indigenous-Led Blockades Occupy Line 3 Pipeline Sites - June 10, 2021

- Rising Up to the Heat: ‘Treaty People Gathering’ Resists Line 3 Pipeline - June 7, 2021

- Activists Serve Denver Wells Fargo Eviction Notice - May 3, 2021

- Appealing Line 3 Pipeline: Supply and Demand at Root of Hearing - March 23, 2021

- Caravan Disrupts Line 3 Construction Routes, Carlton County Triggers Backlash - March 13, 2021

- Treaty Rights Asserted During Creation of White Earth Camp - March 13, 2021

- 70 Water Protectors Cited, 1 Arrested During Line 3 Commemorative Rally - March 4, 2021

- Bipod and Car Blockade Jam Up Line 3 Construction - March 2, 2021

- Three Lock Down Inside Line 3 Pipeline For 6+ Hours - Feb. 21, 2021

- Lockdown to Keep it in the Ground: Line 3 Resistance - Feb. 15, 2021

- Court of Appeals Denies Motion to Stop Line 3 - Feb. 3, 2021

- Opposition to Line 3 Mounts - Jan. 29, 2021

- Resistance to Line 3: Direct Actions Aim to Stop Construction - Jan. 11, 2021

- Enbridge Line 3 Construction Blocked by Activists in Northern Minnesota - Nov. 18, 2020

- Protests After Permits for Line 3 Oil Pipeline Approved - Nov. 17, 2020

- ‘No KKKops, No Pipelines’ Banner Dropped in Minneapolis - Oct. 6, 2020

- “Divest from Climate Change!” Chase Bank Branch Protested on Opening Day - Nov. 7, 2019

- March to Protect The Sacred on Indigenous People’s Day 2019 - Oct. 14, 2019

- Hundreds Rally in Opposition to Line 3 Tar Sands Pipeline in Minnesota - Sept. 28, 2019

- Direct Action in Minnesota as Line 3 Pipeline Approval Reversed - June 3, 2019

- Multi-Agency Task Force Prepares “Rules of Engagement” For Line 3 Protests - Feb. 11, 2019

- ‘Valve Turners’ Shut Down Enbridge Oil Pipelines in Minnesota - Feb. 4, 2019

- Arts, Culture, and Hip Hop Resist Line 3 as Lawsuits Against Approval Continue - Dec. 29, 2018

- Minnesota Police Train at Military Base as Line 3 Pipeline Protests Escalate - Oct. 25, 2018

- Judge Accepts Water Protectors’ Climate Change Necessity Defense - July 18, 2018

- Line 3 Oil Pipeline Approved By Minnesota Regulators - June 28, 2018

- As Line 3 Oil Pipeline Decision Looms, Indigenous Resistance Increases - June 26, 2018

- Interfaith Community Delivers Letter of Line 3 Opposition to Minnesota Government Offices - June 4, 2018

- Minnesota Public Utilities Commission Requests Line 3 Schedule Change - Jan. 10, 2018

- Rally Against Line 3 Minnesota Pipe Yards - Dec. 11, 2017

- Resistance to Line 3 Pipeline Seeks to Save Sacred Manoomin - Oct. 9, 2017

- Direct Action Ramps Up Resistance to Line 3 - Sept. 18, 2017

Cover image shows canoes on Big Sandy Lake arriving at the shores near the hill in which the Mikwendaagoziwag Memorial sits during the 2018 commemoration.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization: